On 12 June 1924, the leadership of the Communist Party of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) decided to undertake national-territorial delimitation in Central Asia. On 24 October of the same year, the Soviet quasi-parliament formalized this decision as legislation. As a result, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan emerged on the political map of the world as union republics and autonomies. At the same time, the already existing Kazakh Soviet Republic significantly expanded its borders. Let’s find out what meaning this centennial anniversary holds today.

- 1. The Prison of Nations

- 2. What If the October Revolution Had Never Taken Place?

- 3. Children of the Nineteenth Century: Marxism and Nationalism

- 4. Classes and Nations

- 5. We Were Born to Turn the Fairy Tale into Reality

- 6. How the Delimitation of Kazakh Lands Occurred

- 7. Was There An Alternative?

- 8. Outcomes of the Initiative to Create a ‘Bright Future’

- 9.

The Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic (ASSR)i

The 1926 Soviet Census showed that the population of Kazakhstan increased to 6.5 million people after the national-territorial delimitation. Among them, Kazakhs constituted the majority, numbering 3.71 million, which is almost one and a half million more than before the delimitation. Previously, the proportion of Kazakhs was approximately 46 per cent, and Russians numerically dominated in the republic due to the Orenburg province (600,000). However, it was excluded from Kazakhstan in 1925.

Map of the republics and regions of Central Asia before and after national demarcation/ from the book by K. Ramzin “Revolution in Central Asia". 1928/Wikimedia Commons

The transfer of the capital of the Kazakh ASSR from Orenburg to Qyzylorda and the inclusion of certain regions of Turkestani

Until 1924, the Kazakh ASSR occupied territories mainly populated by Kazakhs of the Middle and Junior Jüzes. Consequently, the leadership of the Kazakh ASSR was dominated by people from these tribal structures. In 1924, the Kazakh ASSR covered territories mainly populated by Kazakhs of the Elder Jüz. There were also many representatives of a separate group called Kozha, descended from Arab missionaries from the period when Islam was spreading. Notably, this group included the prominent Turkestan party figure Sultanbek Khojanov.1

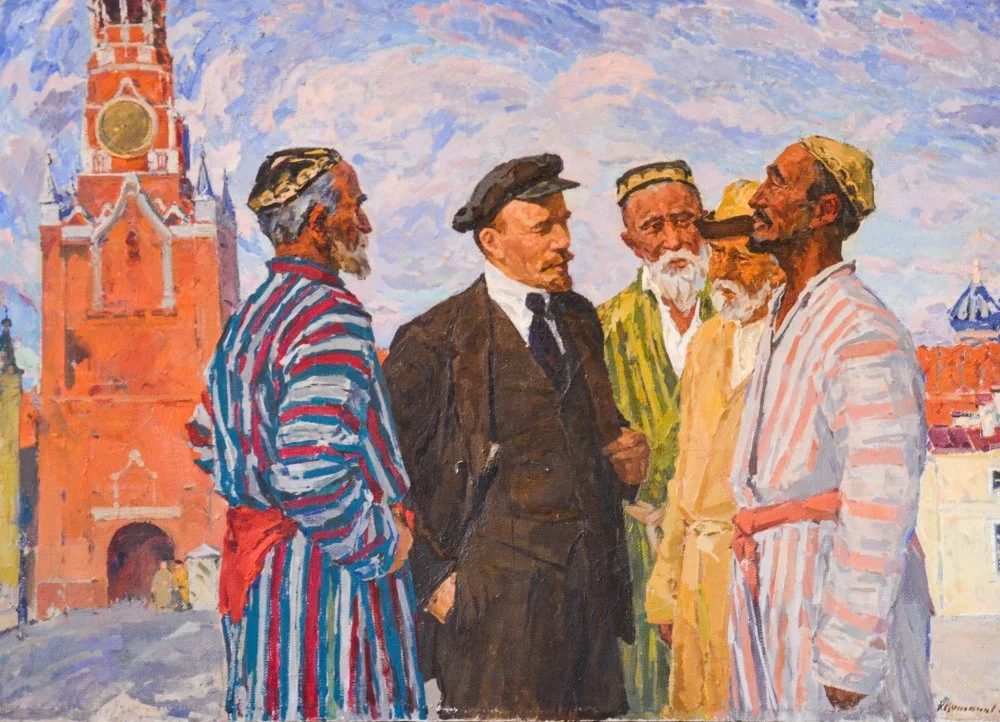

Konstantin Mikhailovich Makharadze “V.I. Lenin". 1972. Exhibition of works by artists of Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia/RIA News

The Prison of Nations

The Soviet authorities grandiosely proclaimed that they had liberated the peoples of the Russian Empire from centuries of oppression and granted them statehood, which was certainly not the case. Moreover, this is precisely the kind of scenario where, according to the great Roman poet Virgil (70–19 BCE), one should beware of Greeks bearing gifts.4

Indeed, in the Russian Empire, all conquered peoples gradually lost any attributes of sovereignty, except for the Grand Duchy of Finland,i

Vasily Vereshchagin «Attacked by surprise» 1856/Wikimedia Commons

The Russian Empire was a unitary state that did not recognize equality among its peoples and religions. And in response to the growth of national movements, the authorities responded with violence and a policy of russification like in Poland. In other colonies, including Central Asia, St. Petersburg preferred not to intervene heavily in local life and customs. Instead, the metropolis exerted influence through different means. Stolypin's agrarian policy5

In contrast, for example, to the British Empire, the Russian Empire lacked a program to modernize colonies that Europeans might consider ‘backward’. Russia did not establish national educational institutions, nor did it make efforts to cultivate a modern national elite capable of more effective colony administration. From the fifteenth century, the government had preferred to appease existing national elites by granting gifts, land, titles, and ranks, thus integrating them into the imperial aristocracy.

What If the October Revolution Had Never Taken Place?

It is incorrect to assume that the Russian Empire would have remained unchanged if the 1917 Revolution hadn't happened. Similar anti-colonial national self-determination processes would have likely unfolded within it as they did in other empires during the twentieth century. By 1917, there was already a widespread demand in various parts of the empire for some form of national autonomy, including in Kazakhstan. For instance, the newspaper Qazaq began publication in 1913.i

'La Liberté De La Russie' Affiche Du Parti Parti Constitutionnel Démocratique (1917)/Alamy

If the Revolution of 1917 had not occurred, the Russian Empire, like the British and French empires, would likely have lost most of its colonies by the 1950s to 1960s and shrunk to roughly the boundaries of present-day Russia. However, we'll never know which states may have emerged, especially in Central Asia. Likewise, many questions were left wide open regarding the future of the Kazakh steppe.

The suppression of the anti-colonial uprising in 1916 could have accelerated the displacement of many Kazakh tribes from their ancestral lands and led to a drastic redistribution of land in favor of Russian settlers. For example, the governor-general of Turkestan proposed seizing all lands from Kazakhs where Russian blood had been spilled.i

Had the February Revolution occurred in Russia without the Bolshevik October, the processes of national self-determination on the peripheries of the empire would have become significantly faster. The Ukrainian Central Rada was convened in March 1917, shortly after Nicholas II's abdication. Concurrently, the provisional government of Russia indicated its readiness to recognize Poland's independence. In May 1917, the First Muslim Congress took a decision about Turkic-Tatar autonomy centered around Kazan.

In July, the Alash Party was formed with the goal of achieving national autonomy for Kazakhstan.

During the same period, July–August, the Bashkirs and the Azerbaijani Musavat Federalist Party also demanded autonomy. The Armenian Dashnak Party, founded in 1890, had grand ambitions not only for Russian Armenia but also Turkish Armenia.

There is ample reason to believe that the All-Russian Constituent Assembly, a representative body in Russia elected in November 1917 and convened in January 1918 to determine Russia's state structure, would have been compelled to acknowledge these growing national movements. In its inaugural session, it declared Russia a federative democratic republic. It is probable that Russia would have soon parted ways with some of its national peripheries, such as Poland and Finland (which declared independence in December 1917), as well as Ukraine. These colonies’ independence would undoubtedly have inspired others to make more radical demands. Therefore, a Russian commonwealth, like the British Commonwealth of Nations, could have emerged by around 1924.

Children of the Nineteenth Century: Marxism and Nationalism

However engaging this discussion may be, its essence lies in acknowledging an obvious fact: the Bolsheviks' designation of regions as national republics and autonomies was largely formal and superficial, a relatively hollow gesture of ‘benevolence’. The national question in Russia was already acutely present. The process of empire dissolution and the formation of national states was already underway and would have continued even without Bolshevik involvement. After the First World War, four colonial empires collapsed—including the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and German—and everywhere, the same thing was happening: new states were being formed.

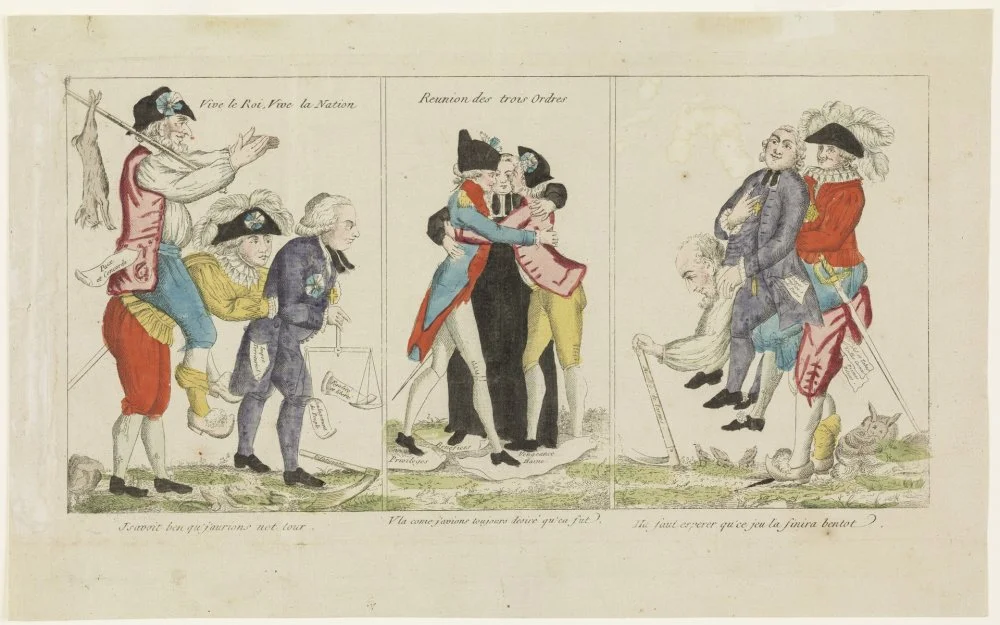

In contemporary Russia, it has become fashionable to attribute the scattering of lands and even the granting of the right to secede from the union, either out of benevolence or short-sightedness, to the Communists. However, critics of Bolshevism often overlook both the essence of its ideology and the unique circumstances of the historical era. The nineteenth century saw the emergence of not only Marxism but also nationalism, which emerged in opposition to colonial empires and advocated for the unity of new nations based on national identities. It is essential here to clarify how the concept of the nation evolved for the intellectuals of the nineteenth century. After the French Revolution (1789–1799), Western Europe embraced the new ideals of freedom, equality, and progress. Large segments of society grew disillusioned with monarchies sanctioned by divine right, with their influence over the clergy, social classes, and feudal structures. The politicians and thinkers of the time viewed the concept of the nation as a powerful tool to reshape states in favor of the broader population rather than for a privileged few serving under a crowned despot.

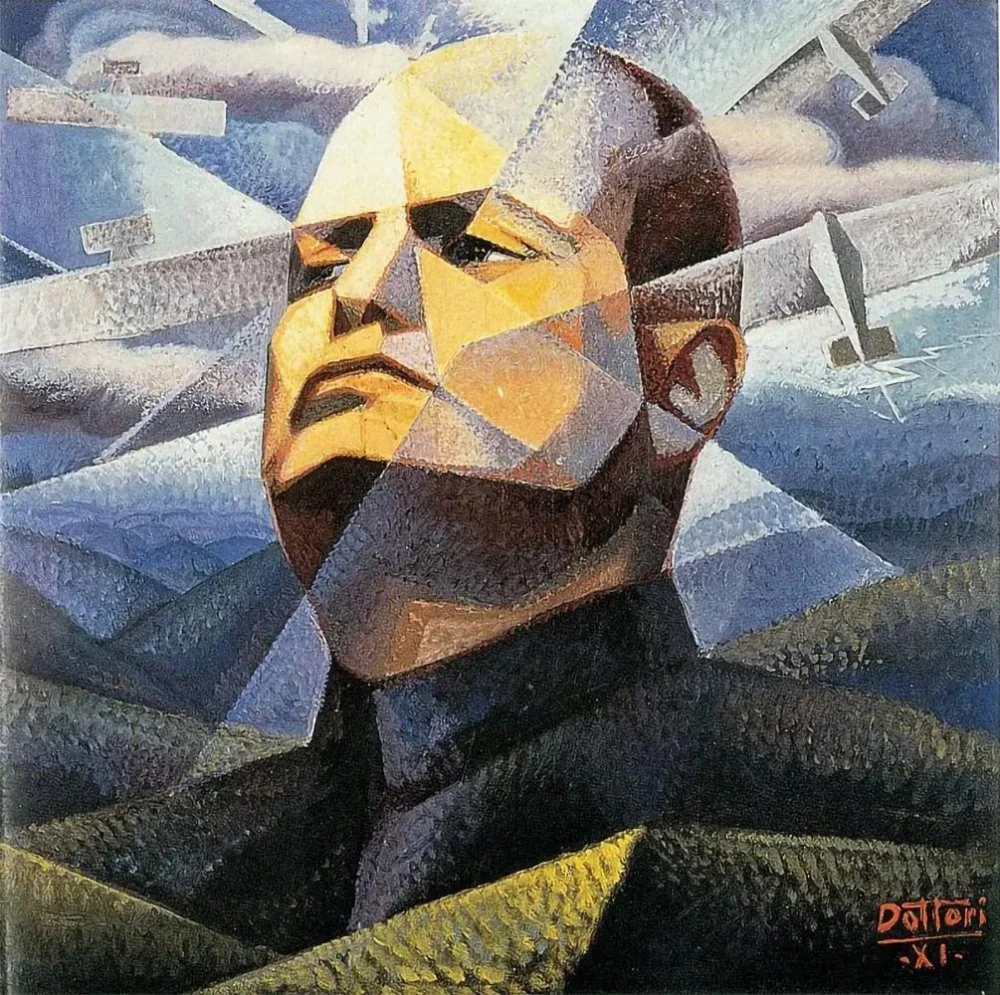

Legend has it that Lenin, then an aspiring Marxist revolutionary, met Benito Mussolini, also a socialist and the future father of Italian fascism, in 1902. Both were just starting their political journeys, which would soon lead them to power: Lenin in 1917 and Mussolini in 1922.

“Long live the King, Long live the Nation - Meeting of the Three Orders" 1789 /Collection of the National Museum of Fine Arts of Quebec

Gerardo Dottori “Duce”, 1933

It's clear that both class and national ideas were boiling in the cauldron of discontent with the old world. Just as nationalism appropriated socialist ideas—Mussolini himself was a populist—socialism also sought to subjugate nationalism. In fact, the Bolsheviks adopted the slogan ‘The right of nations to self-determination’ as early as 1903.

Interestingly, other political forces in Russia, including the Constitutional Democrats (Cadets), moderate socialists, and later the White Army, ignored the national question. Upon assuming power in Siberia in early 1919, Admiral Kolchak notably ordered the dissolution of Alash Autonomy in Semipalatinsk. Underestimating the importance of national movements was one of the reasons for the White Army’s defeat.

Lenin, who aspired to power, understood the power of nationalism well. It compelled people to sacrifice their lives for their homeland and quickly elevated the brave and rootless to the world's highest peaks. However, he saw nationalism as a dangerous alternative to his theory of the class struggle because it placed ‘supraclass goals’ in front of society, thus consolidating it around national elites.

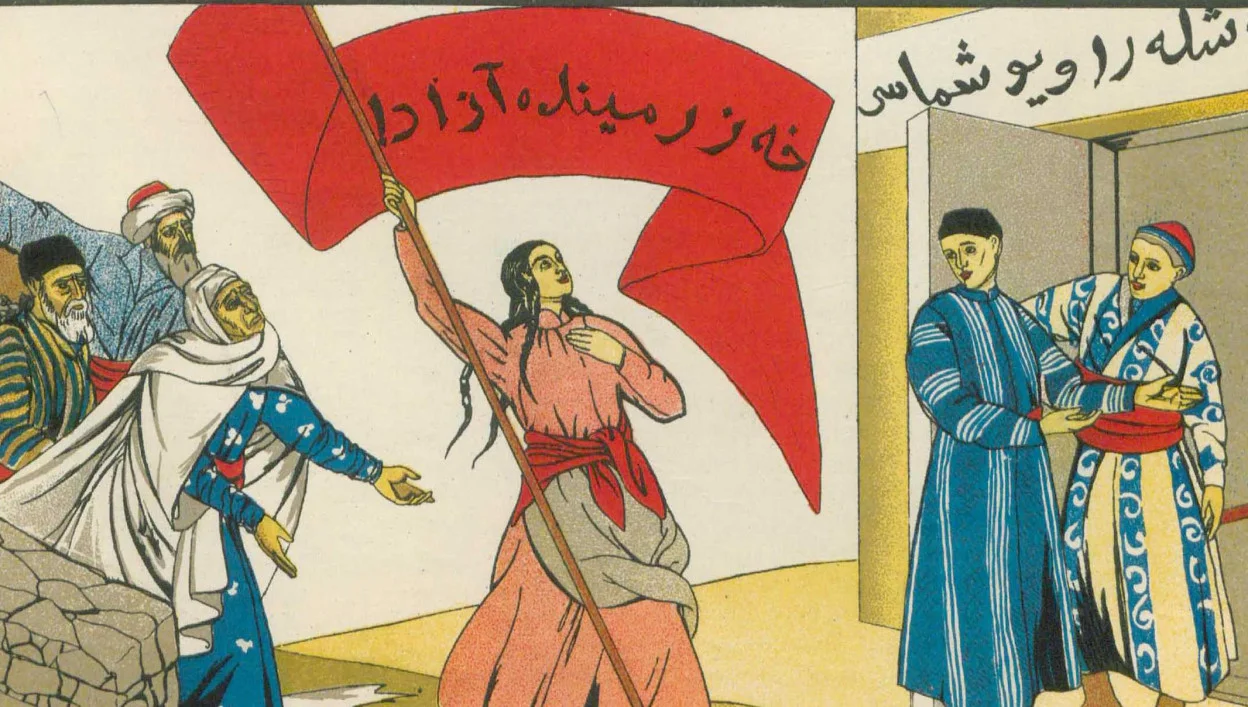

Russian, Soviet, Communist Propaganda Poster, Proletarian Unity Of Peoples. By Mayakovski. 1920/Alamy

Classes and Nations

After 1917, for Lenin, to allow nationalism to spiral out of control meant to risk losing power. Since national liberation movements were objectively inevitable, the Bolsheviks simply had to lead them. So, what did this look like in practice? First and foremost, it was necessary to strip the national movement of its ‘supraclass character’.

The new political language created by the Bolsheviks can sometimes be misleading. It may seem like all the words are familiar, but they often carry completely opposite meanings. Take, for example, the word ‘autonomy’. In ordinary language, this term means independence, the right to act based on one's own principles—but it’s really nothing of the sort.

‘Autonomy is a form,’ Stalin lectured in 1918. ‘The question is what class content is invested in this form. Soviet power is by no means against autonomy; it is for autonomy, but an autonomy where all power is in the hands of the workers and peasants, where the bourgeoisie of all nationalities are not only removed from power but also from participation in the election of government bodies.’

So what then about Alash-Orda, you say? They supposedly secured an absolute majority in the Kazakh steppe in the constituent assembly elections. Those ‘bourgeois nationalists’ who are being ‘revealed by the progress of the revolution’? Their power must be immediately replaced by the ‘dictatorship of the Kyrgyz proletariat’ (as Stalin put it). Naturally, once the Bolsheviks gain control over the Kazakh steppe, the Alash-Orda will be dissolved, its members marginalized, then isolated, and ultimately almost entirely eliminated during the repressions of the 1930s.

Karpov Stepan Mikhailovich "Friendship of Peoples", 1923-1924/Museum of Modern History of Russia, Moscow/RIA

At this point, we must also consider the Bolsheviks' widely promoted right of nations to self-determination, including the right to secede from the Union. Both Lenin and Stalin declared that the Bolsheviks had guaranteed this right—in fact, it was considered sacred. However, secession had to be ‘beneficial to the working masses’, and the party would never agree to leave the masses at the mercy of reactionary leaders like beks, bais, mullahs, and the like.

The Bolsheviks made it clear that in their established system, only the party had the right to speak on behalf of the ‘working people’ and to decide what was in their best interest and when. The ‘workers’ had no choice but to accept this as an axiom, and those who didn't one day simply stopped being around. The Bolsheviks typically referred to this convenient demagoguery as dialectics. Such ‘dialectics’ of class permeated all the social concepts used by the architects of the ‘new world’: state, republic, union, nation, freedom, rights, laws, and humanism.

In the Bolshevik perspective, the Soviet national republic was designed to replace the perceived danger of ‘bourgeois’ nationalism with a less potent, class-based version. This approach also expanded the system's support by promoting social mobility for national leaders among the ‘working people’.

Meeting of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party, 1939. From left to right: Mikojan (standing), Stalin, Molotov, Kalinin (sitting, far right). / Modorow Fjodor./Getty Images

We Were Born to Turn the Fairy Tale into Reality

Marx borrowed the concept of history following a specific logic of progress from Hegel. According to this idea, Marx identified stages of humanity's progressive development from being a primitive communal society to advancing to a communist society. The Bolsheviks believed that by leveraging Marx's supposed logic of the global movement towards communism, they could control and even accelerate history. They could spur time forward, making a monumental leap from the current state of feebleness into a ‘bright future’. Their faith in a ‘progressive’ societal transformation was fervent, akin to a religious conviction, although they referred to it as ‘scientific communism’.

It is clear, though, that without this fervent belief, all their efforts would have been in vain. According to classical Marxist theory of proletarian revolution, the Russian Empire was wholly unsuitable for such a revolution. As a semi-feudal country just beginning to embrace capitalism, it did not require a socialist revolution but a bourgeois-democratic one instead. However, Lenin and his comrades were ardent proponents of social engineering, eagerly striving to transform the archaic colonial empire into the most ‘progressive’ state on Earth.

Some of the nationalities within the Russian Empire, such as Poles, Ukrainians, or peoples of the Caucasus, had already labeled ‘established units’ deserving autonomy by Stalin as early as 1913.i

Ivanov V. Forward to the triumph of communism! Poster 1953/from open sourcess

According to Bolshevik ideology, other nations in Russia were still in the process of being formed because their communities, like those in Central Asia, had not yet embarked on the path of capitalist development. In Marxist theory, a nation is seen as a stage specific to capitalism. Therefore, the Bolsheviks aimed to ‘create’ nations where, according to Marxist doctrine, they could not yet exist. This involved both forging nations from tribes and clans and shedding ‘feudal’ backwardness and modernizing all aspects of it, from social structures to economic practices.

Thus, the establishment of Soviet national republics and autonomies became a grand modernization project that solidified the faltering, weakening Russian Empire around a bright but elusive idea, extending its existence for seventy years. This project aimed to organize large socialist nations, and the objective was not to support the creation or consolidation of colonized nations. Rather, it was to only ensure their formal and visual existence. There was no intention to allow them to freely decide their own futures. The new national elites, integrated into a strict party hierarchy, were tasked with mobilizing the population to dismantle the ‘old world’ and construct socialism on a monumental scale. Despite the outward appearances of nationality and statehood, the Soviet national republic primarily functioned as a tool for mobilization, mandated to faithfully execute the party's will—or rather, the directives of its narrow leadership—on their journey towards a ‘bright future’.

A. N. Samokhvalov Panel "Soviet physical education" 1936/Wikimedia Commons

How the Delimitation of Kazakh Lands Occurred

Delineating the Kazakh lands, which had been consolidated into the steppe region and the Bokei Horde during the imperial era, was relatively straightforward from a nation-building perspective. The unified Kazakh ethnic group spoke a single language (Kazakh, belonging to the Kipchak group of Turkic languages), inhabited the steppe territories, and predominantly led a nomadic life. This is one of the main reasons for the Kazakh ASSR being established as early as August 1920, preceding other Central Asian republics. At that time, Georgy Safarov, a member of the Turkbureau of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), who knew the Central Asia region well, proposed merging its Kazakh population with the rest of Kazakhstan. This took place in 1924, with one notable exception: Tashkent, which was inhabited by Uzbeks and Kazakhs. Despite discussions with influential Kazakh communists in Turkestan, the authorities decided to assign Tashkent to Uzbekistan.

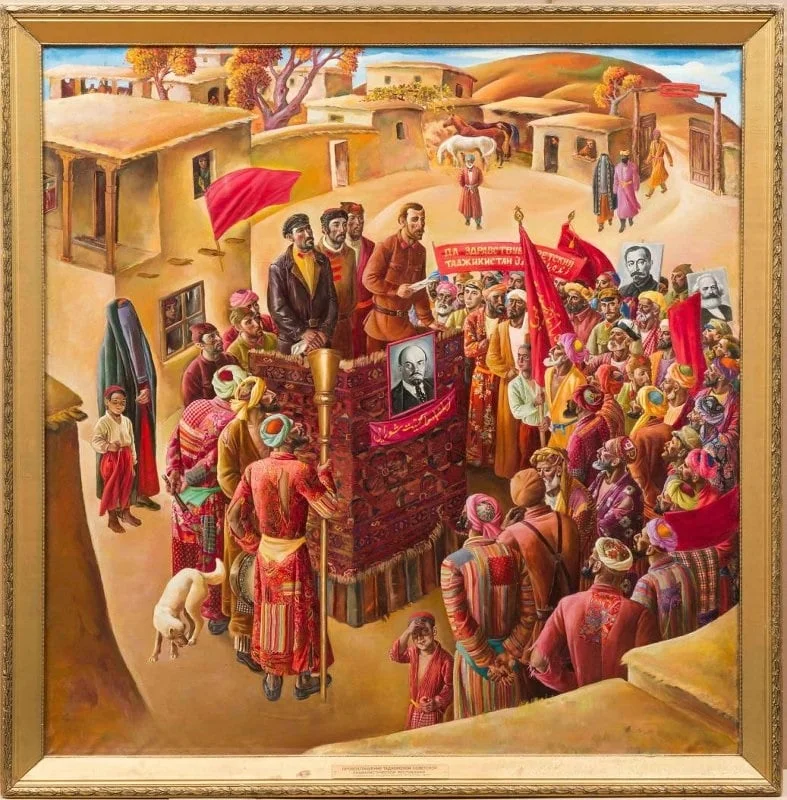

Lenin at a meeting with a representative of the peoples of Central Asia”. Unknown artist. 1981/sovcom.ru

Dividing the vast Turkestan area along national and state lines was an immensely complex challenge. Debate on this issue began with the establishment of the Turkestan ASSR. In June 1920, Lenin gave instructions: ‘Prepare a map of Turkestan (including ethnographic details) with divisions into Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan (Kazakhstan), and Turkmenistan. Further, explore the conditions for either merging or dividing these three regions.’

Interestingly, Lenin's directive challenges the common misconception that the Communists ‘artificially created’ the nations of Central Asia. The Bolsheviks indeed had a general understanding of the region's largest ethnic groups, among whom they now had to establish boundaries. Lenin could be faulted for overlooking the Kara-Kyrgyz (Kyrgyz) and Tajiks, who, ironically, were prominently listed in the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary displayed on the shelf directly behind him in his office. However, the ethnographer-scientists involved in the delineation process were well-informed about these peoples.

Some historians argue that the boundaries of the Central Asian republics were arbitrarily drawn in the Kremlin.

They claim that the Bolsheviks had always had the ancient imperial principle of ‘divide and rule’ in mind, crafting the map to create points of artificial tension. However, Francine Hirsch, the author of a fundamental work on Soviet national policy in the 1920s and 1930s, dismisses this common belief as a myth.

The Bolsheviks consistently emphasized the ‘scientific’ basis of Marxism, preferring practical policies rooted in rational scientific knowledge. They relied on the expertise of ethnographers, geographers, folklorists, and linguists from the old, pre-revolutionary academic tradition. During the imperial era, scholars like S.F. Oldenburg (1863–1934), who, incidentally, was associated with the Cadet Party and served as a minister in the Provisional Government and was an academician of both the Imperial and Soviet academies of sciences specializing in oriental studies and Indology, were viewed with suspicion and distance. The popular perception was that they sympathized with ‘foreigners’ and sought to dismantle Russia.

Under Soviet rule, intellectuals such as L.Ya. Sternberg (1861–1927), Secretary of the Russian Committee for the Study of Central and Eastern Asia and corresponding member of the USSR Academy of Sciences in the department of the Indigenous Minority Peoples of the North, and V.V. Bartold (1869–1930), one of the founders of the Russian school of oriental studies and an academician at both the Imperial and Soviet academies, among others, held prominent positions. They were influential in both the academic hierarchy and the main scientific-practical center for delineation—the Commission for the Study of the Tribal Composition of the USSR and Adjacent Countries, which had been established during the tsarist era in February 1917.

Another important participant in the delimitation process was Gosplan, the chief planning body of the Soviet economy from 1923 to 1991. Gosplan approached the task of defining the borders for the new republics from the perspective of economic feasibility, envisioning the USSR as a federation encompassing regions specializing in cotton and flax, coal and metal, ore and oil, agriculture, and manufacturing.

During the delimitation process, the top party leadership aimed to strike a balance between ethnographers and economists. They paid close attention to the opinions of local and national elites—the Central Asian Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and the Central Territorial Commission on National-State Delimitation in Central Asia. This included people like Isaak Zelensky (1890–1938), who chaired the Central Asian Bureau from 1924 to 1931 and served as the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan from 1929. In Moscow, they meticulously studied the complaints and suggestions submitted directly by local residents after the delimitation exercise of 1924.

Abdurakhmanov Mikhail Abramovich and Yaralova Gretta Alexandrovna “Proclamation of the Tajik SSR” 1975 - 1977/Chuvash State Art Museum

The matter was not about Moscow's arbitrariness or a policy of ‘divide and rule’. One of the experts involved in the delimitation, the distinguished orientalist V.V. Bartold argued that national delimitation was based on the concept of nationhood, an idea developed in keeping with the ‘Western European history of the nineteenth century’ and ‘completely foreign’ to Central Asia.

Indeed, before delimitation began, the majority of Central Asian peoples did not identify themselves in national terms. Even before the revolution, S.F. Oldenburg and L.Ya. Sternberg noted the emergence of national consciousness primarily in the Kazakh steppe, where the Kazakhs had encountered mass peasant migration from Russia and encounters with aggressive colonialism intensified and heightened national sentiments. In Turkestan, however, the situation was different. The different people who lived here intermingled: nomads, semi-nomads, and farmers; Turkic speakers using the Kipchak, Karluk, and Oghuz languages and blended tongues like Chagatai; and Iranians and Sarts, both Turkic and Iranian-speaking. Ethnic, linguistic, religious, tribal, and clan boundaries often did not coincide, and people frequently identified with multiple identities simultaneously.

For settled residents, identity could be constructed around their place of residence—Bukharans, residents of the Fergana Valley, and Tashkentians. If Soviet ethnographers relied solely on linguistic data while delineating the borders of the Belarusian and Ukrainian republics, they had to consider numerous other factors in Turkestan. For instance, Bartold, when outlining the borders of the Kazakh and Kyrgyz republics, accounted for factors such as lifestyle, physical type, and kinship structures. Additional complexity arose from the significant gaps in scientific knowledge. Specifically, certain areas, such as Khorezm (Khiva) and Bukhara, border regions with Afghanistan and China, were referred to as ‘terra incognita’.

In essence, the Bolsheviks' task—to organize national and territorial units in this diverse region that were similar to European models and to draw borders between them—naturally provoked friction. These conflicts began as soon as the new national elites realized that the status of a national republic gave them control over the people, land, and resources, enabling them to marginalize or discriminate against minorities.

Terry Martin wrote, ‘Drawing any national border means creating ethnic conflict. In the Soviet Union, literally tens of thousands of national borders were drawn. As a result, every village, indeed every person, had to assert loyalty to their ethnic group and fight to remain a majority and not become a minority. It is hard to imagine any other measure that could have contributed more to ethnic mobilization and ethnic conflict.’ In Central Asia, such conflicts began immediately after delineation and have continued until recently.

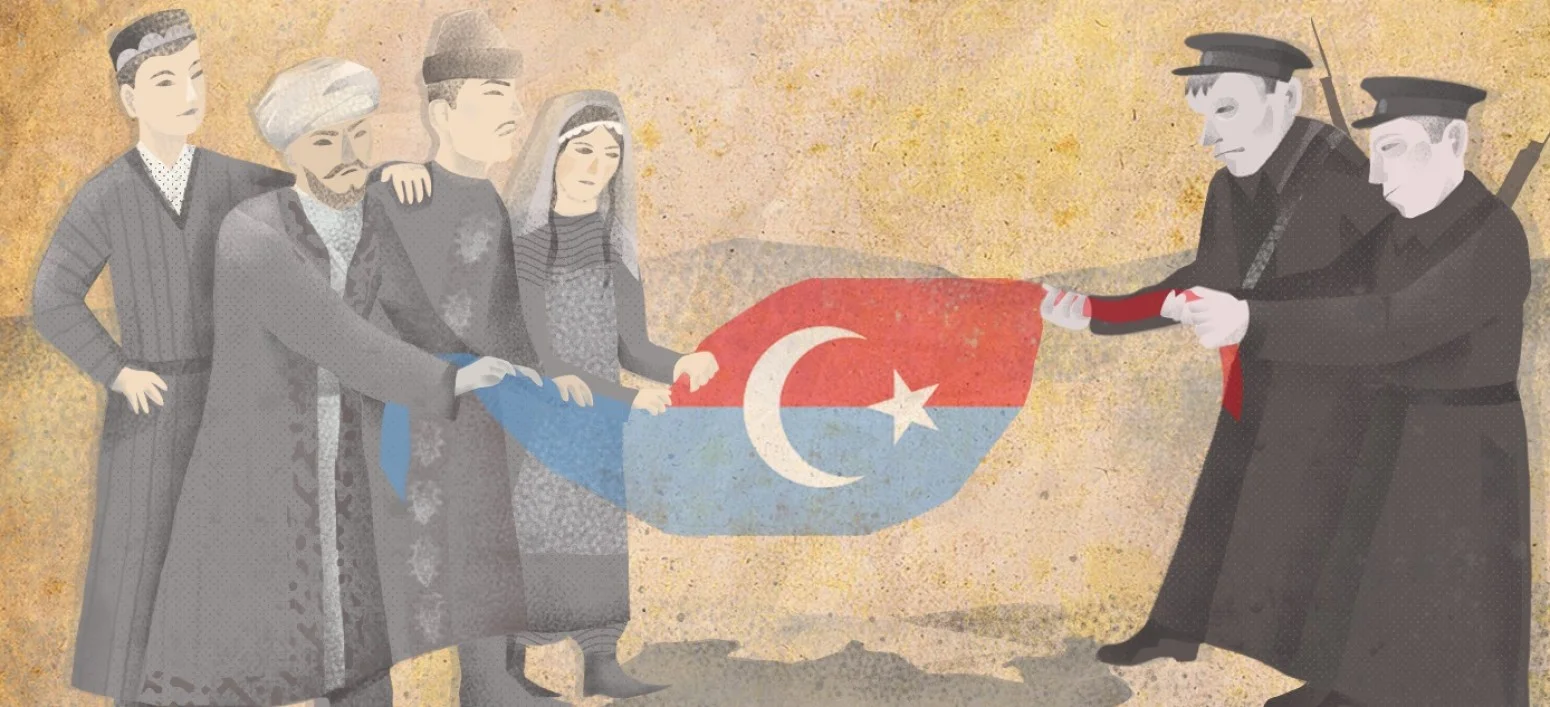

Marina Margarina / Mediazone

Was There An Alternative?

The question of whether there was an alternative is quite intriguing. Even during the period in which delineation was being undertaken, Bartold lamented the loss of ancient state formations like Khorezm (Khiva) and Bukhara, which had held the status of Soviet republics since 1920. Why didn't the Bolsheviks think to preserve them?

In 1920, in Turkestan, the Kazakh party activist Turar Ryskulov and local Jadids (literally meaning ‘reformers’, these were the supporters of Islamic modernism in the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries in the Russian Empire) proposed creating a Turkic Communist Party and a Turkic Republic. Another Kazakh politician and communist, Sultanbek Khodzhanov, advocated for a similar idea, of a Central Asian federation during the delineation period. Why did these projects, however, fail to garner support in Moscow?

Answers to these questions would shed light on the hidden motives behind Bolshevik policies. First, the existence of the multi-ethnic Khorezm and Bukhara, as well as the mega-republic projects, contradicted the Bolsheviks' mono-national principle of state-building, that is one nation, one republic. Second, Khorezm, Bukhara, and the concept of a Central Asian mega-republic were not only transnational but also pan-Turkic and potentially pan-Islamist.

M.V. Maltsev, A.I. Sologub "Ivan Poskrebko in the battle with a gang of Basmachi", 1950

It ought to be mentioned that pan-Turkic and pan-Islamist projects were very popular in the years following the October Revolution but were constantly rejected by Moscow. Thus, in 1919, the Bashkir leader Zeki Velidi Togan (1890–1970) proposed that Bashkortostan and Kazakhstan be united, which was once again disapproved by the Kremlin. Moreover, in 1924, by detaching the Orenburg governorate from the Kazakh ASSR, the Bolsheviks were obviously interested in creating a buffer zone between two Turkic republics.

In 1920, after accusing Moscow of imperialistic ambitions, Zeki Velidi Togan found refuge in Central Asia, where he actively participated in the Basmachi Movement, even becoming the head of the Council of the National Unity of Turkestan. The Basmachi, as the Bolsheviks called them, was an anti-Russian, pan-Turkic, and pan-Islamist movement in which foreign Turks were deeply involved. One of the leaders of the Young Turks, Enver Pasha,7

The fight against the Basmachi, often described as the last act of the Russian Civil War, unfolded amidst significant geopolitical shifts in Asia. In 1923, Mustafa Kemal expelled the European occupying forces and proclaimed the establishment of the Turkish Republic. Earlier, the Afghan emir Amanullah Khan had overthrown British rule, proclaimed independence, and adopted a constitution in 1923.

The experiences of the Young Turks and Young Afghans demonstrated that it was possible to end colonialism and build an independent state without external help, especially since the help from Moscow could easily bring unwanted consequences. Similar reformist ideologies, such as the Young Khivites, Young Bukharans, and Jadids in general, wielded considerable influence in Turkestan and had extensive connections with communists both at home and abroad. Thus, the parade of sovereignties on the southern borders of the USSR made the Bolsheviks anxious. It's no wonder they hastened to establish Central Asian Soviet republics to serve their own agenda, swiftly suppressing any local initiatives for national statehood.

Amanullah Khan & Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, 1928/open sources

Outcomes of the Initiative to Create a ‘Bright Future’

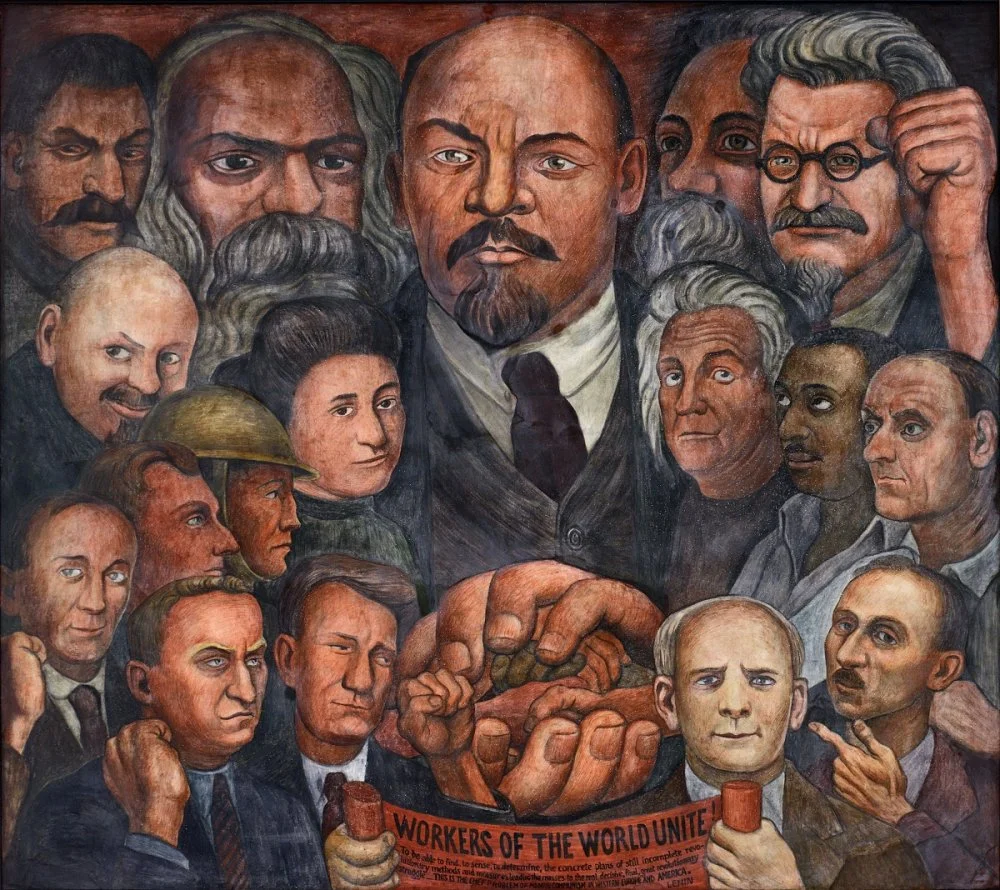

Having spent much of their lives in exile, neither Lenin nor the Bolsheviks knew Russia well. Lenin even confessed, ‘I know little about Russia. Simbirsk, Kazan, Petersburg, exile, and that's almost all!’ However, Lenin and the Bolsheviks were undeterred by this lack of detailed knowledge. They staunchly believed in Marxism, which they considered scientifically irrefutable. This doctrine, crafted by Karl Marx and funded by the capitalist Friedrich Engels, was proclaimed as the ‘will of the working people’. Having granted themselves the exclusive right to interpret this doctrine, the Bolsheviks created an unprecedented apparatus of violence in the world—the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’. In the pursuit of a ‘bright future’, this dictatorship could physically annihilate entire classes, abolish long-standing social orders, relocate populations, and seize the labor and property of millions of people.

It took decades before experience—the ultimate criterion of scientific truth—revealed the fallacies in all the constructs of Russian Marxists. These ultimately led to the economic, national, and political crises of the late 1980s and the subsequent collapse of the empire they had built.

Diego Rivera “Proletarian Unity” 1933/Nagoya City Art Museum, Japan

The term ‘modernization’ typically evokes purely positive connotations. However, Soviet modernization was marred by countless victims and tragedies. Matt Payne aptly noted: ‘Soviet national policy acted as both the destroyer and creator of the new Kazakh nation.’ Indeed, traditional Kazakh society, with its centuries-old traditions, perished during Soviet modernization. The Bolsheviks seemed to want to impose a new identity on the Kazakhs—a socialist Kazakh nation.

The efforts, achievements, victories, and tragedies of the generations who built Soviet Kazakhstan became part of this new identity.

Yet paradoxically, the memories of their former traditional tribal society and their statehood never faded, holding significant importance for Kazakh self-perception even to this day. This once again underscores the fallacy of Russian Marxists' fantasies that dismantling the traditional economic order would give birth to an entirely new Soviet person. Overall, the Bolsheviks underestimated all they dismissively termed ‘superstructure’—customs, culture, religion, historical, and familial memory.

At the beginning of this article, I pondered extensively on what would have transpired if the 1917 revolution had not occurred or if the February Revolution had taken place, but the Bolsheviks had failed to seize power in October. There is no doubt that in either scenario, the Republic of Kazakhstan would have emerged on the world map—it was only a matter of time. This was the logic of the historical process already underway in the Russian Empire. With a more evolutionary unfolding of events, the modernization of Kazakh society would likely have been more gradual and less tragic. However, the Bolsheviks managed to prolong the life of the Russian Empire in its new, edited, and expanded form. Nevertheless, history ultimately restored everything to its rightful place.

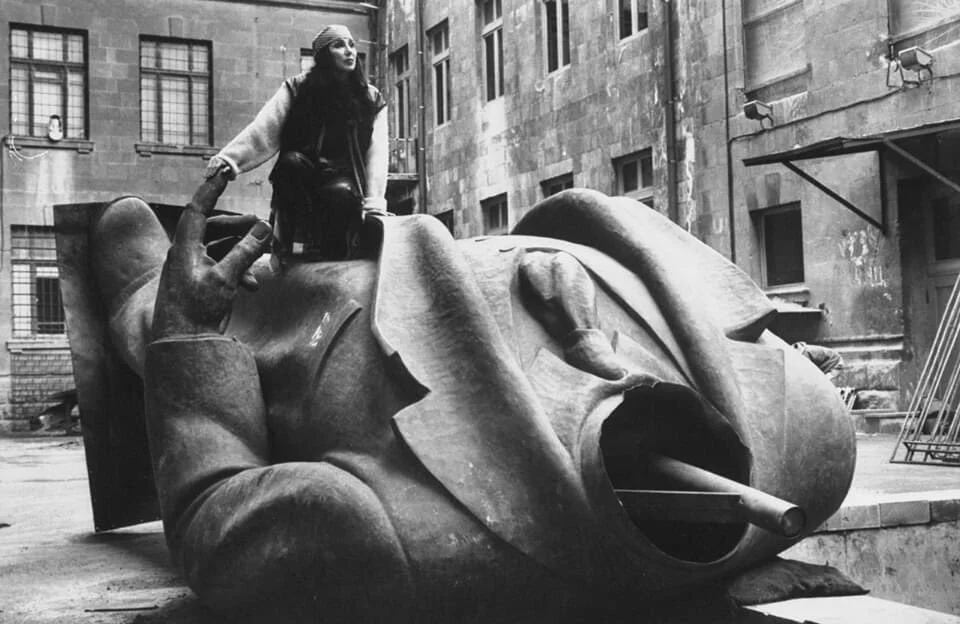

Armenian-American singer Cher sitting on the broken statue of Lenin, Yerevan, Armenia 1993/Mkhitar Khachatryan