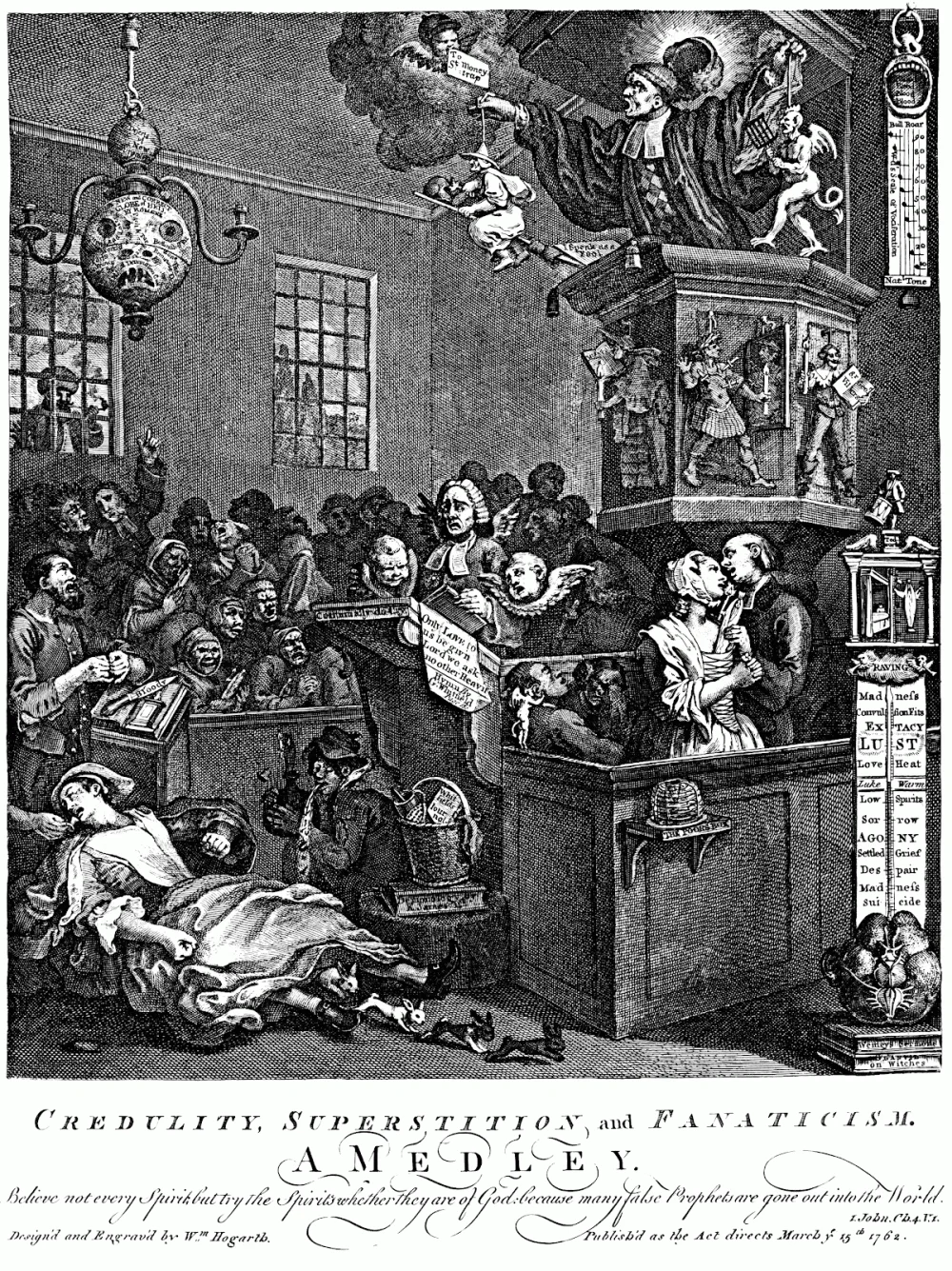

William Hogarth. Etching. Mary Toft, apparently giving birth to rabbits. 1726/Alamy

For centuries, mainstream medicine and its practitioners held complicated, and often harmful, attitudes toward women’s health, especially their reproductive health. Until almost the twentieth century, these misconceptions enabled the belief that women were capable of producing ‘monsters’, the word used with a touch of dark humor!

For a long time, gynecology was the most backward branch of medicine. Even ancient experts had a bizarre understanding of the female body, and the information on this subject provided by respected physicians such as Hippocrates,1

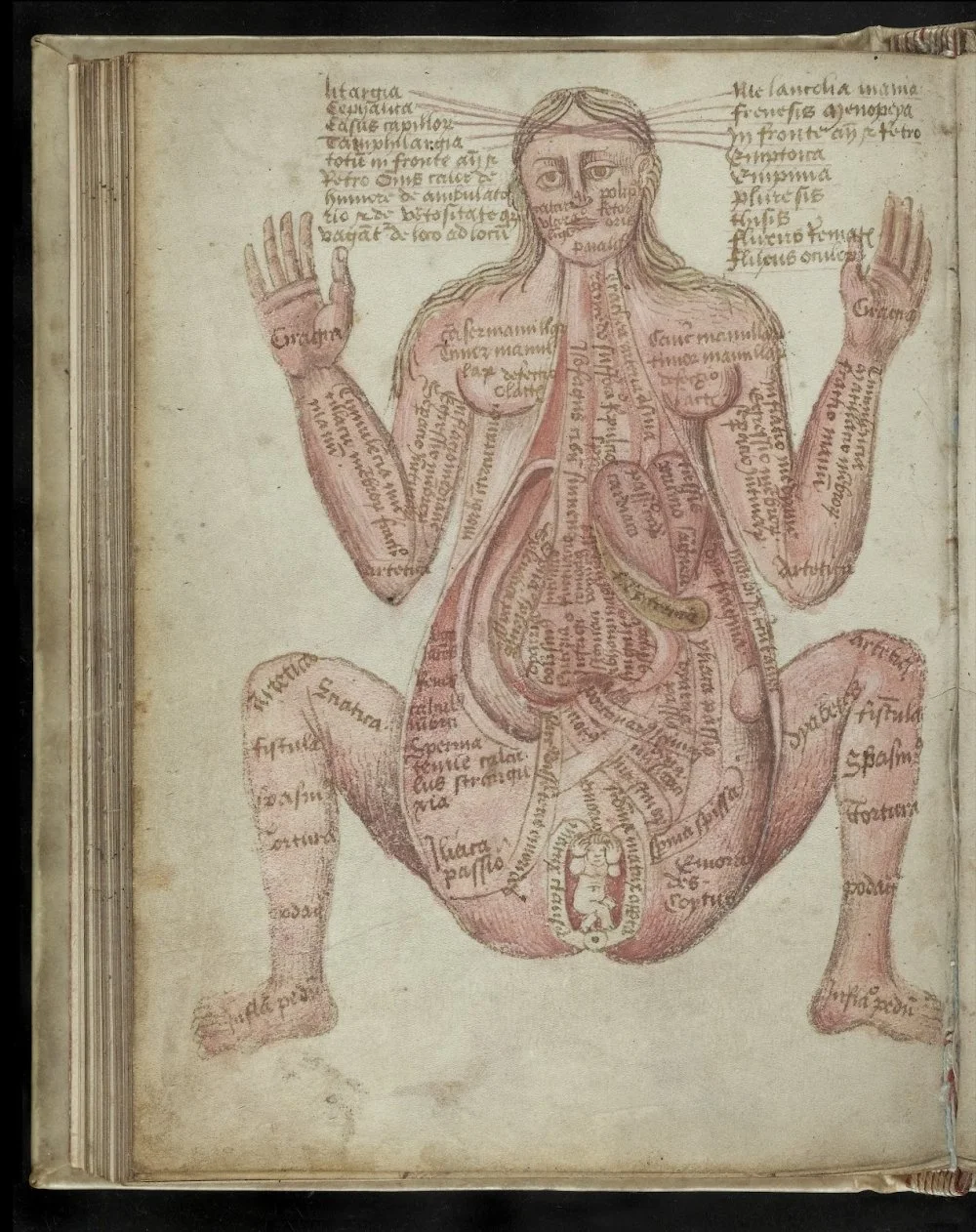

Anathomia. Pregnant woman, seated legs apart, flesh tinted. Archives & Manuscripts/Wikimedia Commons

Given that European medicine up until the nineteenth century regarded the authority of these ancient physicians as unassailable, it should come as no surprise that the ‘fabulous’ information about the female body and its functions derived from their works was regarded as immutable fact for more than 1,000 years.

This was partly due to the conflict between official doctors and midwives, both of whom fiercely defended their right to practice medicine. Legislators tried to separate them into different corners, drafting laws according to which, for example, the (male) doctor could not examine the (female) patient himself but could only sit in a corner behind a curtain and make recommendations to the midwife—he would intervene personally only in the most extreme cases. This custom existed in Europe and Asia for a very long time, persisting in some places well into the twentieth century.

Throughout history, the norms of public morality, religious requirements, the most ancient rituals and rites have shrouded female reproductive life in secrecy and fallacies. As a result, even in the most enlightened times, doctors had a severely limited understanding of women’s diseases and believed the most ridiculous superstitions to be true.

Mother being handed a swaddled child, 16th century/Wikimedia Commons

For example, the fetus was considered to be formed in the womb by the influence of, among other things, the ‘impressionability’ of the mother. Thus, any strong emotion that a woman felt could have a serious effect on the offspring. If the mother, frightened by something, pressed her hand to her face, the child would have a birthmark from the eye to the mouth. If a planter’s wife watched black slaves pick cotton, she gave birth to a black baby. A pregnant woman could only eat fish all the time she was pregnant: no wonder the child was born deaf and dumb.

So she’s grown up—me to spite!

Little wonder she’s so white:

With her bulging mother gazing

At that snow—what’s so amazing!i

The theory of ‘maternal imprinting’, as it was called, was generally favorable for women because it required that every pregnant woman be treated with the utmost care. If the family had the means, it was customary to give a pregnant woman all the attention possible—she should not be sad or worried; she should eat the most delicious and varied food; and she should be surrounded only by beautiful things and people (for example, the healthiest and most attractive girls were assigned as maids).

It wasn’t until the mid-eighteenth century that the medicinal sciences began to be skeptical of the maternal imprinting theory—and we have the illiterate maid Mary Toft to thank for it.

Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614). Portrait of a Pregnant Woman, Possibly a Self-Portrait/Wikimedia Commons

Mary was a servant who had married a clothier named Joshua Toft. She suffered a miscarriage in August 1726, but when September arrived, she still looked pregnant, and at the end of the month she went into labor again. The woman was visited first by her neighbor Mary Gill and then by her mother-in-law, Ann Toft. She gave birth to a cat-like creature in front of them.

The family told their other neighbors what had happened and sought the help of John Howard, a Guildford-based male midwife with thirty years of experience. He was on call, armed with all the knowledge he had about the female body.

John Laguerre. A copy of a portrait of Mary Toft. 1726/Wikimedia Commons

Ann Toft gave him the animal parts she said she had taken from her daughter-in-law during the night. The next day, Howard came back and helped Mary ‘give birth’ to the new animal parts. He helped, as a doctor was supposed to do in those days, by sitting behind a screen and talking to the women who were fussing around the woman in labor. Their combined efforts resulted in the appearance of what looked like a skinned rabbit’s foot. The strange contractions continued throughout the next month. On one occasion, Mary produced a rabbit’s head, cat’s feet, and nine dead rabbits in Howard’s presence.

Believing in the reality of monster births, Howard sent letters to some of England’s most eminent physicians and scientists, as well as to the king’s secretary, reporting the medical phenomenon he had observed. The concerned king sent the court physician Nathaniel St. André to examine the case and give his opinion. After some investigation, St. André concurred with Howard that the birth of the rabbits had not been faked.

St André depicted in a satirical engraving of 1726/Wikimedia Commons

Both men believed Mary’s explanation: that she had been frightened by a rabbit while working in the fields during her pregnancy and that she had dreamed of the same rabbit the next night. Toft’s story caught the attention of the newspapers of the day and soon spread far and wide. Mary became a celebrity—and not just locally: the political writer John Hervy, second Baron Hervey, wrote of Mary:

‘Every creature in town, both men and women, have been to see and feel her: the perpetual emotions, noises and rumblings in her belly are something prodigious; all the eminent physicians, surgeons and man-midwives in London are there day and night to watch her next production.’

William Hogarth. Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism. April 1762/Wikimedia Commons

It was soon discovered that women in other parts of the country were giving birth to amazing creatures as well. In the medical journals of the time, we can find descriptions of newborns such as ‘a strange creature resembling a giant naked chick’, and ‘a recognizable piglet embryo’.

This series of miracle births continued for some time until a German surgeon, Cyriacus Ahlers, who was practicing in England at the time, began to investigate the case. After examining parts of the rabbits ‘born’ to Toft, he found grains and grass inside, indicating that they did not come from Mary’s womb (even the great theory of maternal imprinting was still not suggesting that this miracle woman had fields and lawns growing inside her).

Toft was brought to London, where her body was fully measured, and she was placed under constant observation. In an attempt to save his reputation, St. André invited the famous physician James Douglas to participate in the study and tried to convince him that a woman could indeed give birth to an unidentifiable animal. Much to his disappointment, Douglas also suspected a hoax.

Three pregnant women/Wikimedia Commons

When she was isolated from her relatives, Toft was unable to give birth to any more cats or rabbits. Later, one of her maids reported that she had been bribed to bring a dead rabbit into the ‘expectant mother’s’ room. Toft eventually confessed to the fraud but did not explain her motives. At first she was even arrested, but the public created such a wave of ridicule against the doctors and the royal court that it was decided not to bring the case to trial, and Mary was released without charge.

As far as Nathaniel St. André and Howard, the affair cost them their medical careers. And even two centuries later, one can only marvel at how little male doctors knew about such a trivial medical event as childbirth, and how different they considered women to be from men.