Scientists at the Abbasid Library in Baghdad. Arabic miniature. 13th century / Alami

Al-Farabi, a philosopher, mathematician, music theorist, and one of the greatest scholars of the East was born in the ancient city of Otrar, located in the south of Kazakhstan. In the ninth to tenth centuries, al-Farabi undertook a grand and nearly unattainable endeavor for his time—he attempted to unite Western and Eastern thought.

Today, in our global world, we are constantly amazed by the cultural gaps that open up when we speak of the unity of human nature, principles, or the banal questions of what is good and what is bad. The current need to be politically correct and other norms of a new ethics only exacerbate the situation, throwing veils of silence and invisibility over the noise of the real state of affairs in the world.

Well, maybe it could work. One simply needs to ignore the fact that, for example, a Korean and an American were essentially people from different planets for two or three hundred years, that they are people with completely different ways of thinking and perceptions of the world, and that the internet and global culture will somehow bring them to at least a relatively common denominator. Well, we'll repeat that this approach has some prospects. But what did the scholar from Baghdad, who took on the task of translating Aristotle’s teachings into an Eastern tradition, hope to achieve in the ninth and tenth centuries CE, inevitably changing the structure of the thought of the Greek philosopher and his own mentality in the process? The answer is nothing. He found a precious gem, admired it, and limited it to his own style.

The consequences of this action are undefined, because, as we know, history does not tolerate subjunctive moods. If it hadn’t been al-Farabi, there would have been another curious scholar in his place—or perhaps the chasm between civilizations would be even wider now. What is certain, however, is that it was Aristotelian logic, albeit reinterpreted, that became the basis of modern Islamic theology, albeit in a very specific way, and it was al-Farabi who became the carrier and disseminator of this logic. Of course, a whole host of thinkers followed him along this path, including the incomparable Ibn Sina. But undoubtedly, al-Farabi was one of the first.

Al-Farabi. Medieval Miniature / Wikimedia Commons

A Stranger from Nowhere

There is a joke that goes ‘In reality, the Iliad and the Odyssey were not written by Homer, but by a completely different blind old man.’ The punchline of the joke is that we know almost nothing about the creator of these ancient poems except that he was supposedly blind, and it seems that he only became famous in his old age, and so it doesn't really matter whether he was that blind old man or not.

It's a similar story with al-Farabi, though we do know a little bit more about him. There are approximately 150 treatises attributed to him, and most of them were almost certainly written by the same hand and mind. The structure of his thoughts and his language are always unique, although numerous imitators make it difficult to identify authorship. Therefore, as a scientific phenomenon, as a pure idea, as an author and creator, he undoubtedly remains alive, vivid, and recognizable. He was unquestionably a real figure.

However, the physical embodiment of a person is a much more complex thing. Starting with his place of birth and nationality, al-Farabi’s biographers boldly include him among the Turks, the Persians, the Sogdians, and sometimes even the Arabs, which is most controversial. He had many biographers, though the first of them wrote their works only in the twelfth to thirteenth centuries CE and, therefore, could not have known anyone who had seen the philosopher in his childhood. This means they did not differ much from us in terms of this hot pursuit. Luckily, the philosopher's name didn't provide any grounds to suspect him of having Jewish, Chinese, or European origins, or we might have encountered different versions of his origins. His name serves as the focal point for debates surrounding al-Farabi, and fortunately, being an Eastern name, it carries substantial information about him.

It is very likely that his full name was Abu Nasr Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn Tarkhan ibn Uzlak al-Farabi al-Turki, though part of this construction is a controversial issue. Due to this name, we can assume that he had a son named Nasr—although we know nothing about his family and descendants as there is no evidence that he was ever married. It is very likely that the scientist's personal name was Muhammad. He was the son of Muhammad as well, and his grandfather was named Tarkhan, although ‘Tarkhan’ also means ‘nobleman’, and so this prefix may simply indicate that al-Farabi belonged to a relatively prominent family. Uzlak is either the name of his great-grandfather or a family nickname. But the fact that the philosopher was born in Farab is undisputed since he has indicated as being ‘from Farab’ himself. However, we do not know exactly which Farab he was born in as several regions carried this name. This is not surprising, as in the Sogdian language, the meaning of this word creates many local toponyms as it means ‘riverbank’, ‘river crossing’, ‘or a place near the river’. Most researchers, however, believe that the Farab being referred to is the one that is now located in southern Kazakhstan, once a major economic center with its capital in Otrar.

Al-Farabi's bloodline is completely unimportant as the concept of nations in the modern sense did not really exist at that time. Europeans had not yet identified themselves as French or Germans, and to a resident of the Samanid empire, it was generally irrelevant who was in front of them—an Arab, a Turk, a Persian, or even an underdeveloped Bactrian. Religious, tribal, political, and clan conflicts certainly existed, but a city dweller's origins were much less important than the political party or scientific school to which they belonged.

We do not even know for certain if Arabic was not al-Farabi’s native language—he studied Arabic philology in Baghdad, but still even Arabs themselves could study high Arabic in its written form. Languages in general are complicated, and al-Farabi was a natural polyglot. According to his biographers, he knew seventy languages although this claim is either exaggerated or they included dialects, and there were more written languages on Earth at the time, but there is no reason to suspect that al-Farabi knew, say, hieroglyphics or any European languages other than Greek. However, since in his commentaries on translated works, he pays much attention to the accurate translation of words, often referring to one or the other dialect, we almost certainly know that he was proficient in several Turkic languages, Sogdian, Persian, Arabic, Greek, and apparently Syriac. Finally, he also wrote in Arabic, the international language of that time.

Thus, it should be noted that we know almost nothing about al-Farabi's childhood except that it began in 870 (or 872), apparently in Otrar or nearby, and the voice singing over his cradle was perhaps doing so in Turkic. After that, the curtain closes and darkness falls.

Georg Macco. Qalawun Mosque in Cairo. late 19th–early 20th century / Alamy

A Man of Science and a Judge

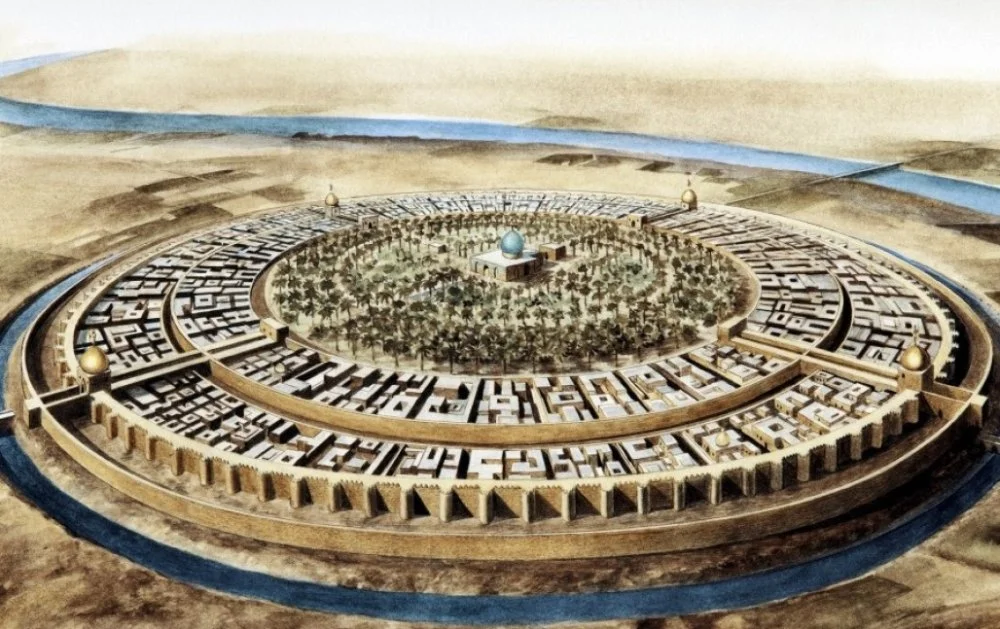

Later, we discover an adult al-Farabi living in the Round City of Baghdad,1

Baghdad in the 10th century / Jean Soutif

In Baghdad, al-Farabi is unlikely to have been a judge for very long as we soon find him engaged in a completely different occupation—studying, teaching, and writing. He wrote a lot because he stumbled upon an overlooked treasure trove—piles of texts by classical Greek authors that were faithfully translated in Baghdad schools, mostly by Nestorian translators.2

First, the translations into Arabic were, to put it mildly, not perfect. While they may be considered accurate from a modern perspective, the accuracy is limited to the standards and understanding of the present time. The fact is that the requirements for the purity of the Arabic language almost did not allow borrowing, and any innovation in speech or writing could be perceived as lahn, a linguistic mistake that nullifies the significance of what was said. Those who try to impose prohibitions on ‘foreign words’ do not realize that ‘purity’ in language is inevitably synonymous with ‘poverty’, but intellectuals today are not the only ones who fail to understand this. In Baghdad of the tenth century CE, things were even stricter as mocking the sacred language of the Quran could get you into trouble. Therefore, translators did their best, usually choosing relatively suitable words from the Arabic language based on meaning, or even inappropriate ones, but what else could they do? When you are describing a concept for which there is no equivalent in your own culture, how can you find the word for it?

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries CE, Russian translators of European books elegantly solved the problem by simply using calques. For example, the German word Vorstellung has no equivalent in Russian thought and language, so what would you do? You’d translate it piece by piece! The prefix vor means ‘pre-’ in Russian, the root stellen means stavit (to set) and the ending ung is replaced with the Russian enie. The result is predstavlenie, which means acquaintance, or introducing a person to someone. Readers will figure out what it means on their own, and if they don't, too bad for them.

Strict laws against lahn in the Arabic language didn't allow for such tricks. Therefore, it was especially difficult to deal with metaphysics, essences, substances, and accidents. The word accidentia, for example, meaning ‘a non-essential property of a substance’ was translated as arad (عارض), which has ‘accident’ or ‘symptom of illness’ amongst its meanings. Is it close enough? It'll do!

The resulting texts were absolutely fantastic. It is not surprising that many Arabic-speaking readers, politely poring over works written in such a remarkable way, carefully put them on the farthest shelf of the darkest cabinet for scrolls, feeling a slight regret for the fate of the Franks, whom the creator had blessed with such a mess in their brains. Al-Farabi, although not an Arabic speaker himself, and possessing a stunning ability for languages, understood that the issue was not with the original texts but with the translations. He somehow managed to grasp the essence behind the jumble of words. Perhaps he trusted the word of his Christian and Jewish friends, who told him Aristotle was a genius!

And so, al-Farabi set out to study Greek with all the fervor of his brilliant mind, and along the way, he studied Arabic thoroughly, as well as logic, medicine, natural sciences, and physics. He studied in Harran under Yuhanna ibn Haylan (Johannes Philoponus), a Christian philosopher, and learned Greek and ontology from Nestorian Abu Bishr Matta ibn Yunus, another Christian.

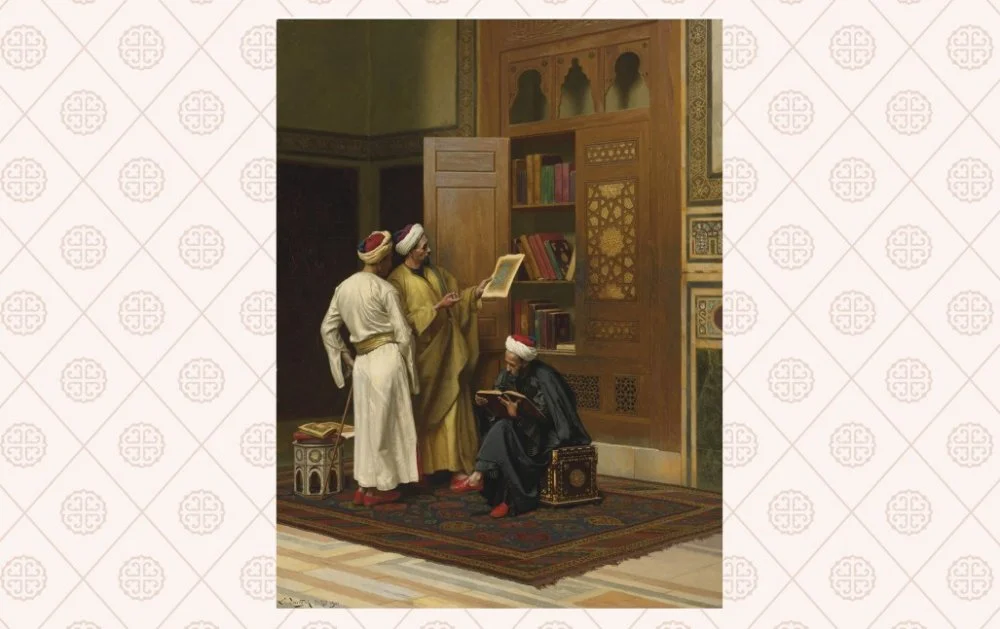

Ludwig Deutsch. The Scholars. 1901 / Wikimedia Commons

At the same time, al-Farabi began to write commentaries on the works of the ancient Greeks, first on Aristotle, moving to Plato and then Galen. In these commentaries, he not only talked about the difficulties of translation and in properly understanding the text, but as a diligent weaver, he intertwined Western thought with Eastern thought and was quite willing to easily overturn some of the assertions of the original sources, simplifying some things and complicating others. With this synthesis of cultures, he actually created a new, unique school of thought, where formal logic was interwoven with mysticism and even illogicality.

This, however, often leads to errors in reasoning, even when it comes to natural sciences. Al-Farabi's fans, for example, like to mention his experiments with vacuum, sometimes even talking about al-Farabi's discovery of the vacuum. Well, yes, he did write a short essay on the vacuum. But he argued there that there is no such thing as a vacuum—all of it was nonsense.

This is what al-Farabi says in his treatise titled On Vacuum: ‘From the above said, it is clear that the discussion about the vacuum is not a necessary conclusion. What they considered to be absolute emptiness is actually space filled with air ... This concludes our discussion about vacuums. Endless praise to reason!’

But this opinion is not significant in the larger picture—Galen, and even Aristotle, have put forth many erroneous ideas and fiercely defended them. But such is the fate of scientific thought—to wander in darkness, to be mistaken, to fall and rise again. The main thing that al-Farabi did was open the gates from one world to another; he immensely enriched the thought of the East with a whole layer of new concepts. And indirectly, he also enriched the intellectual treasure trove of the West since the reinterpreted and supplemented works of the Greeks returned to Europe several centuries later in the form of the works of, for example, Avicenna (Ibn Sina) or Averroes (Ibn Rushd).

Exile

With his works, al-Farabi stirred up a hornet's nest, for even without him, the scientific circles of Baghdad were then in an extremely agitated state, awash with turbulent emotions. The confrontation between the schools of ‘local, Arab’ and ‘foreign’ science was raging, and experts in the Quran and Arabic writing, with all their might, met all this logic, rhetoric, chemistry, and mathematics that representatives of Greek, Indian, and Iranian cultures brought to the ‘house of wisdom’.3

According to legend, al-Farabi loved fried lamb hearts more than any other dish, and presumably after receiving that pension, he could occasionally afford such a treat.

Another matter is that being in the center of such important events can sometimes be harmful to one's health. Al-Farabi created a completely new system of views and ideas, known as the al-Farabi School, which, for years to come, largely determined the path of development of Islamic civilization.

However, for creating a qualitatively new science in the caliphate, al-Farabi paid dearly. Detractors were always making for him, and to save if not his life then his freedom, he was forced to leave Baghdad in his sixties and wander for some time across the space from Persia to Egypt, with few means of supporting himself. In some places he gave lectures, in some he briefly worked as a teacher, and in others he wrote a new work and had his colleagues disseminate it.

Finally, the great thinker settled in Damascus, where he was forced to work as a garden guard. It is known that he was paid so little that he could afford only one portion of oil for a lamp every night, which was clearly not enough for a man who still wrote and read a lot. Fortunately, at that time, not far away, in Aleppo, lived an enlightened emir named Saif al-Dawla, who gathered a good cohort of thinkers and scientists under his authoritative wing. After discovering who was gardening in Damascus, the emir made al-Farabi an offer. It was not a position as a court scientist, as the bustling palace environment would have been torture for a modest and weary philosopher. Instead, the emir proposed a more than decent pension, equivalent to four dirhams per day, for the rest of al-Farabi's life. This was a considerable sum. A jug of thirty liters of dates cost one dirham then, and with one dirham, one could buy flour for pancakes for a family for two weeks; a sheep cost one dirham, and a lamb was only half a dirham. According to legend, al-Farabi loved fried lamb hearts more than any other dish, and presumably after receiving that pension, he could occasionally afford such a treat. Damascus was a beautiful, ancient city, with much greenery and flowing rivers—it was very similar to his native Otrar. Oil for lamps was abundant. There were also a few loyal students and like-minded colleagues. And so, al-Farabi almost certainly continued to write there. We do not know the exact dates of many of his works, but it is very likely that they were written by him in Damascus. It is certain that he completed his pedagogical-sociological work Treatise on the Views of the Residents of the Virtuous City there.

Raffaello Sanzio. The Athenian School. A fragment depicting Aristotle and Plato. 1510-1511 / Wikimedia Commons

Al-Farabi left for us a significant legacy comprising historical and socioeconomic treatises, works on music, astronomy, physics and medicine, as well as mathematical and philosophical works. But most importantly, he left behind a changed paradigm of civilizational thinking for both Eastern and Western cultures. He became one of the first bridges that brought those cultural continents closer to each other.

He died at the age of approximately eighty, in 950 or 951, during the winter in Damascus. According to another story, he was killed by robbers during a trip to Ashkelon, where he was going to join a scientific debate, but this remains uncertain. However, it is known that the emir of Aleppo came to his funeral and read a prayer written on four papyrus scrolls.

The end of any life is always sad, but one would like to believe that until his very last hours, al-Farabi was light, active, and his heart was filled with joy. The fact that at the age of eighty, he set off on a winter journey to distant Ashkelon suggests that he maintained physical strength until the end. His days passed in peace and prosperity, and hopefully without turbulence, among the greenery of vineyards, punctuated by evening conversations by lamplight with understanding people and the distant hum of a big lively city, accompanied with books and beloved music.

SELECTED QUOTES BY AL-FARABI

On a Virtuous Town:

"A town where the unity of people aims at mutual assistance in matters which lead to true happiness is a virtuous town, the same as the society where people help each other for the purpose of achieving happiness is a virtuous society. The nation, whose all cities help each other to achieve happiness, is a virtuous nation. Similarly, the whole earth will become virtuous if all nations help each other to achieve happiness."

On the Union of Souls:

"When one generation of people perishes, their bodies rot, and their souls, freed from the body, attain happiness. Other people of the same level appear after those, they take their place, and continue doing what those perished did. When these new ones die, their souls reach the same degree of happiness as their predecessors, and each of them unites with one similar to itself in appearance, quantity, and quality. Since they are incorporeal, their union, no matter how extensive, does not cause any mutual spatial constraint. This happens because they do not occupy any space at all, and how they meet and unite with each other is no similar to the way it happens with bodies."

On the Relativity of Differences among People:

"... different virtuous towns and virtuous nations may have different religions, although all of them believe in the same happiness and strive for the same goals."

Ibn Khaldun and the Qadi. Arabic miniature of the 14th century / Wikimedia Commons

References

1. Аль-Фараби. Философские трактаты. Алма-Ата, 1972.

2. А.Х. Касымжанов. Абу-Наср аль-Фараби. М., 1982.