No other disease is surrounded by as many myths as leprosy. The term has become synonymous with irrational fear, stigma, and rejection, so much so that even today, we refer to those facing ostracism and exclusion from society for various reasons as 'lepers.' In this way, leprosy has become a metaphor.

The Disease of the Outcasts

This attitude is primarily explained by the fact that leprosy significantly alters one's appearance. The afflicted person begins to rot alive; their skin becomes covered in reddish-brown spots that turn into foul-smelling ulcers, and they lose sensitivity, increasing the risk of cuts and burns. The face becomes disfigured to the point of complete unrecognizability (the so-called ‘Leonine facies’), the voice grows hoarse, and vision deteriorates, often leading to complete blindness. It’s not surprising that leprosy patients inspired dread, even among their own family and friends.

Woman with leprosy. Book "Voyage en Islande et au Groënland" by Louis-Eugène Robert. Illustrated by Antoine Maurin and published in 1835-1836/Alamy

The word ‘leprosy’ typically evokes images of medieval history: unfortunate outcasts, banished from society, forced to live no closer than ‘a stone's throw’ from the city walls, announce their presence with the sound of a bell, and keep their faces covered.

A man, wrapped in white, appeared on the path, emerging from the forest thicket ... A bell rang with each of his steps. He had no face: a white sack, with no holes even for eyes, covered his entire head; the man was feeling out his way with a stick.

A deadly fear gripped the boys.

'Leper!' Dick gasped.

'His touch means death,' said Matcham. 'Let’s run!'

'Why run?' Dick countered. 'Can’t you see he’s completely blind? He’s feeling out his way with a stick. Let’s lie still and not move; the wind is blowing from us to him, and he’ll pass by without harming us. Poor fellow! He deserves pity, not fear!'

'I’ll pity him when he’s passed us,' Matcham replied.

The sinister ringing of the bell, the tapping of the stick, the veiled, eyeless face, and above all, the awareness that he was not only doomed to death and suffering but also rejected by people—all of this filled the boys with overwhelming dread. The man drew nearer to them, and with each step, they lost more of their courage and strength.

R. Stevenson, The Black Arrow

A leper beggar in the form of the devil. An engraving by an unknown follower of Hieronymus Bosch. 1474-1566/Rijksmuseum/Wikimedia commons

Stigma

Although we often associate leprosy with the Middle Ages, its history begins much earlier. The commandments of the Old Testament regarded leprosy as a divine curse and required that those afflicted be cast out from the community of the living:

And the leper in whom the plague is, his clothes shall be rent, and his head bare, and he shall put a covering upon his upper lip, and shall cry, Unclean, unclean. All the days wherein the plague shall be in him, he shall be defiled; he is unclean: he shall dwell alone; without the camp shall his habitation be. Lev. 13:46

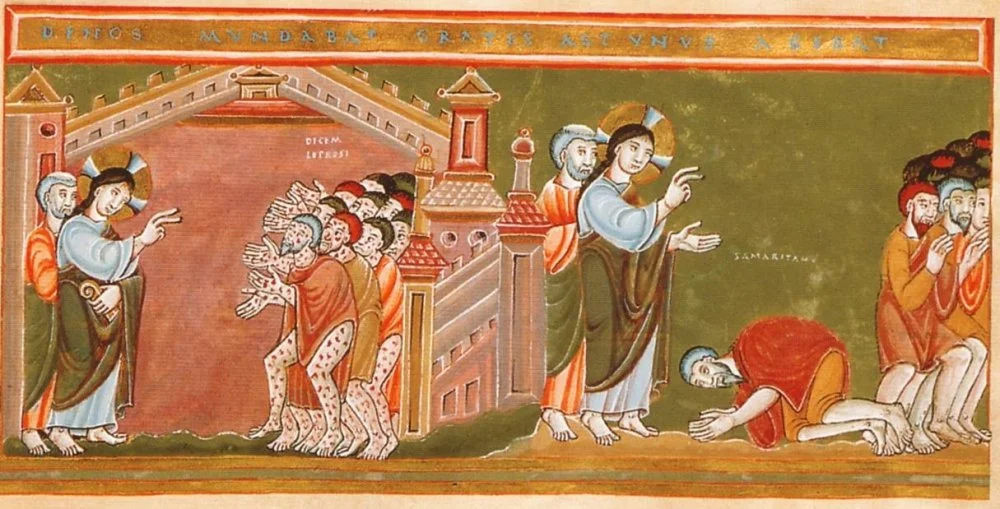

Christ cleans leper man. Mosaic in Monreale Cathedral (12th century)/Wikimedia Commons

At the same time, the age-old issue with ancient disease descriptions persists, although we can't definitively identify leprosy as these texts lack clinical details, let alone laboratory indicators. It wasn't until the nineteenth century that clearer diagnostic criteria were established, which helped to avoid confusion. Before that time, many of those diagnosed with leprosy were likely suffering from other diseases.

Moreover, the word translated as ‘leprosy’ or ‘lepra’ (tzara'at, צרעת) in the Old Testament refers not only to the disease but also to mold on clothing and walls. Both spots on the skin and mold on the walls are considered signs of ritual impurity. In any case, these were considered visible indicators of a divine curse. Leprosy was primarily understood as a 'disease of the soul', with its physical symptoms viewed merely as an outward manifestation. Any contact with an afflicted person was considered potentially dangerous. In bygone eras, the attitude toward those with leprosy differed markedly from our modern concerns about contagious illnesses. Rather than fearing infection, people dreaded divine retribution.

Jésus guérissant dix lépreux. Codex Aureus Epternacensis (vers 1035-1040)/Wikimedia commons

Leprosy Kills Slowly

Leprosy is one of the oldest known diseases, but it took a long time before it was clearly defined and distinguished from other illnesses that also cause skin changes. Modern scientific evidence leaves no doubt that leprosy has an infectious nature. Its pathogen is known, its clinical picture is described, and treatments have been found. However, in ancient and medieval times, leprosy was not only poorly differentiated from other diseases, but there was also significant uncertainty about how it was transmitted. While plague spreads rapidly like wildfire, leprosy is the least contagious of all infectious diseases. There are many cases where a person in prolonged contact with a leprosy patient does not contract the disease. Moreover, leprosy has a very long incubation period and can manifest itself several years after infection. Transmission occurs primarily through airborne droplets but only in cases of close and prolonged contact with the infected. Therefore, there was no clear answer to the question of why a particular person contracted leprosy.

When it came to the causes of the disease, there were typically two answers. The illness could either be a punishment from the Almighty for sins or be inherited. The great Avicenna cautiously suggested that leprosy might also be transmitted through contact with the afflicted: 'Sometimes this is facilitated by the corruption of the air—either by itself or due to proximity to lepers, for this disease is contagious and is sometimes inherited, arising from the [poor] nature of the seed drop from which [the afflicted] was created by inheritance.'i

Clerics With Leprosy Receiving Instruction From A Bishop. Omne Bonum, de James le Palmer, London, 1360-1375/Alamy

The Leper's Rattle Sings in My Hand

In Europe, those suspected of having leprosy underwent an ‘examination’ that was supposed to involve a doctor, a priest, and a representative of the local authorities. However, due to the severe shortage of medical professionals, this often took place without the presence of a doctor. Symptoms of the disease were identified as spots on the skin, changes in facial features, a hoarse voice, and the ability of the afflicted person to fall asleep on stone steps, as leprosy reduces sensitivity. If the diagnosis was confirmed, the patient underwent a symbolic burial ceremony and was considered excommunicated ‘from the community of the living, but not from God's mercy’, according to the official wording. Leper colonies were required to be located a ‘stone's throw’ from the city walls, and contact between the sick and the healthy was minimized as much as possible.

It is easy to assume that no treatment for leprosy existed in ancient and medieval times. However, this is not entirely accurate. In medical treatises, we sometimes encounter utterly unimaginable remedies that were believed to alleviate the condition of those afflicted.

Know that viper meat ... is one of the most precious medicines for lepers. The viper is cleaned and boiled, as we will further describe, and its meat and broth are consumed. Many lepers recover after drinking wine in which a viper has died or which a viper has licked; this may happen accidentally or as an attempt to kill the leper so that he may die and be freed from his suffering and thus spare others from his presence; this is done in obedience to dreams and visions ... With this method of treatment, the benefits may not be immediately apparent but then suddenly become evident, though sometimes recovery is preceded by a temporary loss of sanity for a few days. A sign that the viper's benefit is taking effect and that it is time to stop its use is when the leper begins to swell suddenly, sometimes loses his sanity, and then sheds his skin entirely, after which he recovers ... Here is another remedy prescribed for this disease. A black viper that has shed its skin is killed, buried in the ground, and kept there until it becomes infested with worms. Then it is dug up, together with the worms, and dried; the severely afflicted leper is given this for three days, one dirham a day, with honey wine.i

Leprosy: Leper With Begging Bowl And Bell Or Rattle Which He Is Shaking To Warn That He Is 'Unclean'. Engraving After A 13th Century Manuscript 'Miroir Historial' Of Vincent De Beauvais/Alamy

Fear, disgust, and revulsion these were the feelings lepers evoked in medieval Europe. At the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris, the oldest of European hospitals, all sick people, including those with contagious diseases, were admitted, except for lepers. Lepers were thought to be aggressive, plagued by insatiable lust, making it dangerous for women to approach them. In the novel about Tristan and Isolde, lepers appear when the king searches for a punishment more dreadful than burning for his wife:

Just then, there had come up a hundred lepers of the King's, deformed

and broken, white horribly, and limping on their crutches. And they

drew near the flame, and being evil loved the sight. And their chief

Ivan, the ugliest of them all, cried to the King in a quavering voice:

'O King, you would burn this woman in that flame, and it is sound

justice, but too swift, for very soon the fire will fall, and her

ashes will very soon be scattered by the high wind, and her agony be

done. Throw her rather to your lepers where she may drag out a life

for ever asking death.

And the lepers answered:

'Throw her among us, and make her one of us. Never shall lady have

known a worse end. And look,' they said, 'at our rags and our

abominations. She has had pleasure in rich stuffs and furs, jewels and

walls of marble, honor, good wines, and joy, but when she sees your

lepers always, King, and only them for ever, their couches and their

huts, then indeed she will know the wrong she has done and bitterly

desire even that great flame of thorns.'i

A leper was seen as an enemy—dangerous and vengeful, seeking to avenge their misfortune. Such beliefs were unquestioned in medieval society. In 1321, a conspiracy of lepers was ‘uncovered’ in France, where they were allegedly plotting to poison all the wells and thus destroy or infect the entire population of France and Spain with leprosy. Jews were suspected of being behind the plot. According to a medieval chronicler, one of the accused confessed that a wealthy Jew had given him a packet of poison and 10 livres, promising even greater rewards if the leper could recruit others of his kind into the conspiracy. As a result, Jews in Spain were banned from touching food at the market. Many of the accused were executed, and measures against lepers were tightened.

Execution and burning at the stake of lepers and Jews, fourteenth century, Great Chronicles of France/BNF, FR 2606.

Despite this, in the Middle Ages—and even afterward—cruelty toward lepers coexisted with instances of remarkable altruism. The Gospel recounts the healing of a leper by Jesus in Galilee.

When He was come down from the mountain, great multitudes followed Him. And, behold, there came a leper and worshipped Him, saying, Lord, if Thou wilt, Thou canst make me clean. And Jesus put forth His hand, and touched him, saying, I will; be thou clean. And immediately, his leprosy was cleansed. Matthew 8:1–4

Saint Francis of Assisi confessed that he gained his spiritual experience through interactions with lepers. He initially felt horror and disgust toward them but managed to overcome these feelings and shared his life with the outcasts. During the Crusades, the Order of Saint Lazarus was founded with the mission of aiding those with leprosy. Its master could only be a leper. In Cambodia, there is a popular legend about a leper king whom everyone abandoned, except for four concubines who remained faithful to him.

Leprosy In France : A Leper Colony In Middle Ages. Illustration from ‘La Medecine Populaire’. 1881/Private collection/Alamy

By the end of the fifteenth century, leprosy gradually disappeared from Europe; leper hospitals became empty and were often repurposed—most commonly into asylums for the mentally ill. The chilling fear also seemingly receded, and lepers were often seen begging at church doorsteps alongside other beggars. There are accounts in historical sources of beggars who deliberately pretended to be lepers, painting spots on their bodies to elicit sympathy.

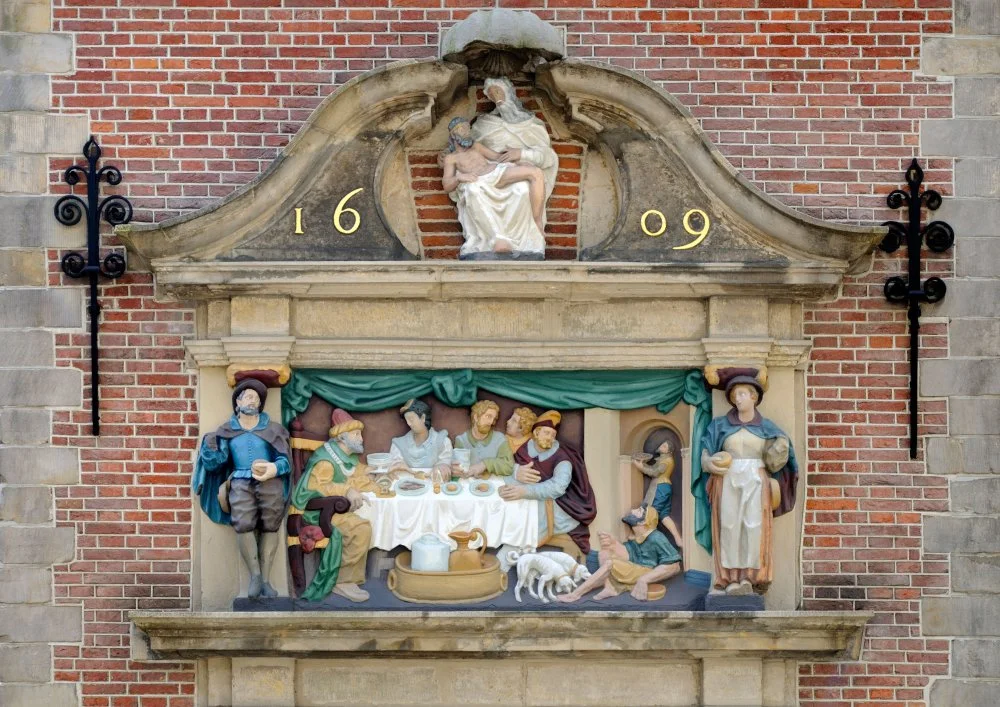

Gouda, Netherlands. Lazaruspoortje (1609) - Former Entrance To Leper Hospital. Sculpted Pediment Above Doorway/Alamy

It took centuries for leprosy to move from the realm of charity to that of medical analysis. For a long time, the care of lepers remained the prerogative of the Church.

Former "Sanatorio De Abona", The Leprosy Station Of Abades, Tenerife, Canary Islands/Alamy

‘We, the Lepers’

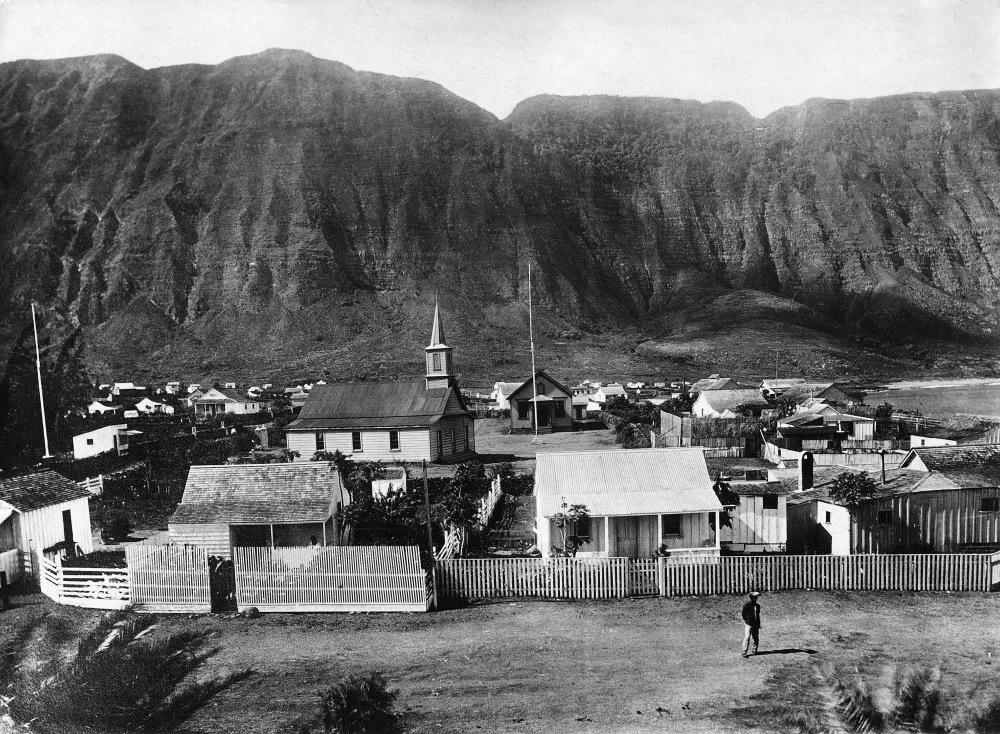

In the mid-nineteenth century, leprosy began to spread rapidly among the local population of the Hawaiian archipelago. On the island of Molokai, a leper settlement was established. Patients were sent there forcibly, with only the opportunity to say goodbye to their loved ones and to write a will. There were known cases of healthy people simulating leprosy to avoid separation from their families, as no one ever returned from the leper colony. Living conditions there were horrific: the sick lived in abject poverty, without medical care. As an eyewitness wrote, ‘Physical decay was accompanied by mental and moral decay, increasing at a terrifying rate: incredible filth (even water was scarce), violence ready to erupt at the slightest provocation, the exacerbation of the basest instincts, removal of all sexual restraints, the enslavement of women and children, alcoholism and drug addiction, widespread theft, the revival of idolatry and superstitions.’

United States of America (USA), Hawaii, Molokai: Leprosy colony. - probably in the 1910s/Getty Images

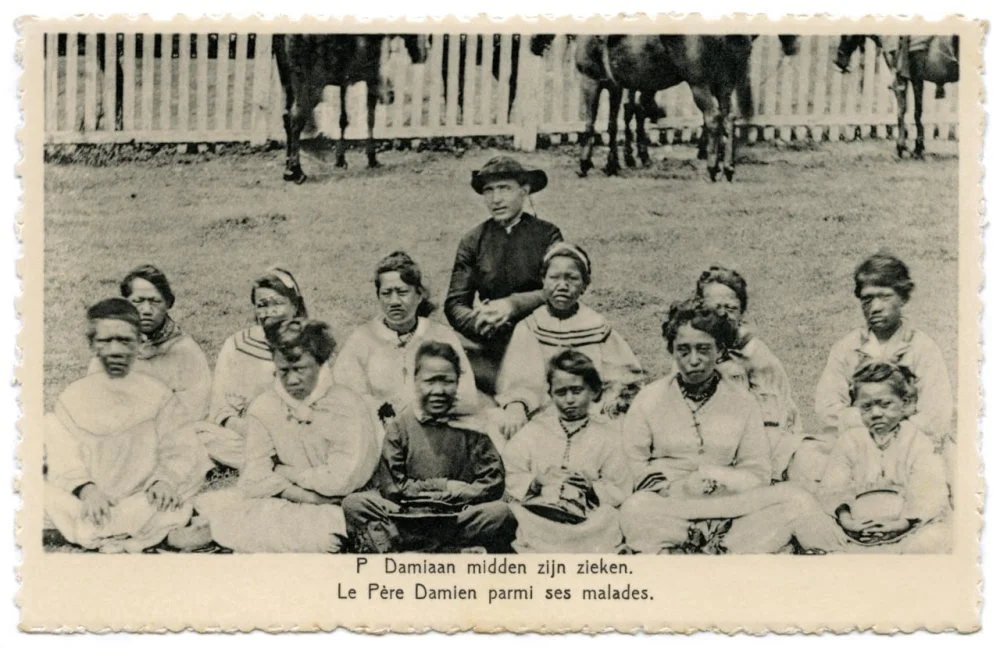

In 1873, a thirty-three-year-old Catholic priest, Father Damien de Veuster, arrived at the leper colony on Molokai. He thought he would stay on the island for a few weeks but ended up remaining there for many years.

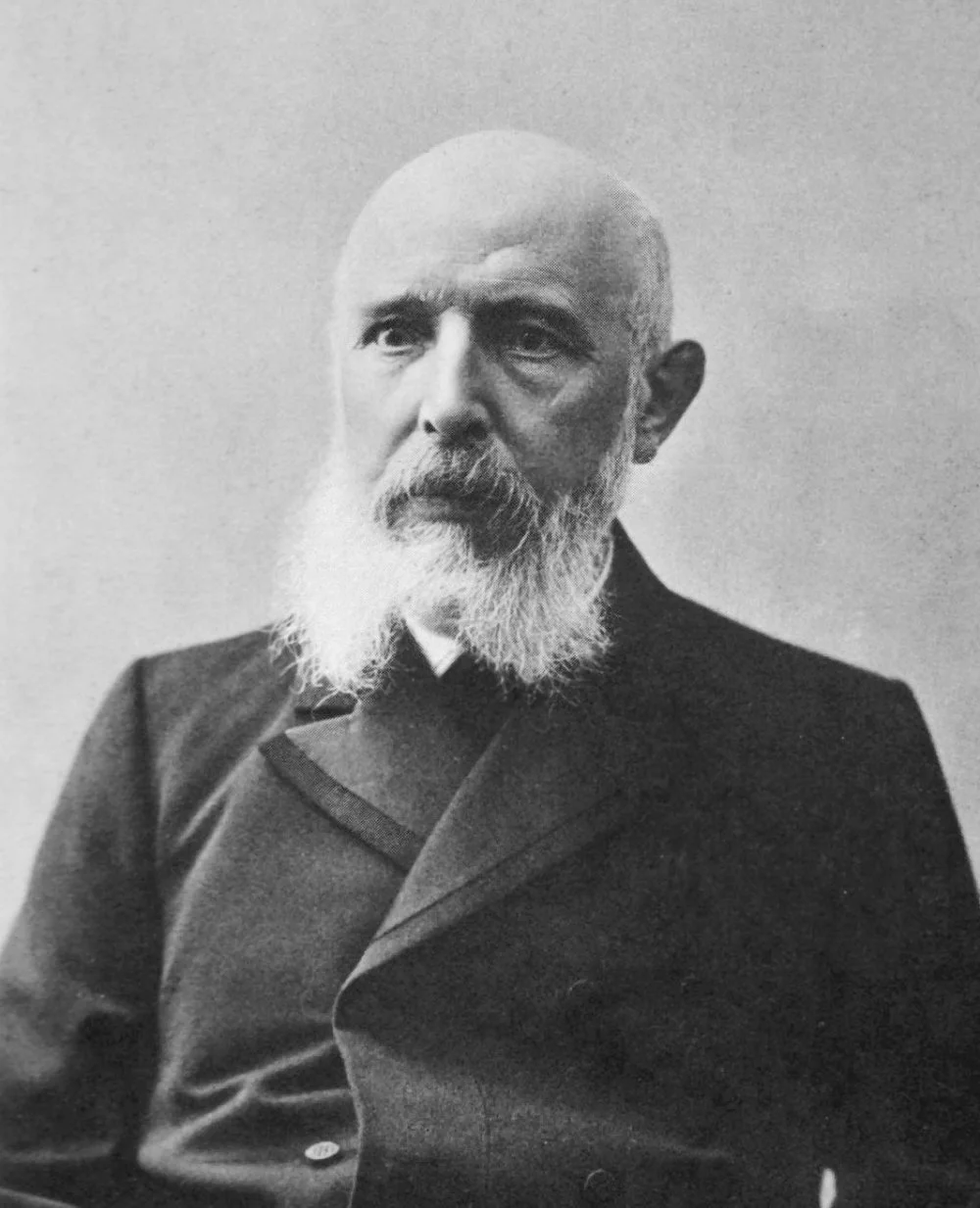

Father Damien of Molokai, Belgium (1840-1889) who died saving lepers/Getty Images

What Father Damien saw in the leper colony shocked him. By the time he arrived, there were about 600 patients living in filth, poverty, and chaos. There was no proper housing, no hospital, no church, not even a cemetery. The Hawaiians believed that their misfortunes were brought by white people and refused to accept white priests and doctors, openly calling the Department of Health the ‘Department of Death’. The authorities, on the other hand, claimed that the disease was the result of the natives' immoral behavior and focused solely on isolating the sick rather than treating them.

Father Damien began his work by establishing a cemetery and conducting funeral rites. Dignified death and funeral ceremonies marked the first steps toward improving conditions in the leper colony. Over time, a church, hospitals, schools, and two water supply systems were constructed. The patients regained their human dignity and ceased to feel that their lives were meaningless and useless.

Father Damien, A Catholic Missionary And Priest, With The Kalawao Girls Choir At The Leprosy Colony On The Island Of Molokaʻi, Hawaii In The 1870s/Alamy

In his first sermon, he did not address the congregation with the traditional words, ‘My brothers,’ but simply said, ‘We, the lepers.’

What followed was to be expected: Father Damien contracted leprosy. He died after spending sixteen years among the lepers, praying for them and assisting them, overcoming the fear and revulsion that these unfortunate souls inspired. Known as the ‘Apostle of the Lepers’, he was canonized by the Roman Catholic Church in 2009 and is venerated as the patron saint of victims of infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS.

Father Damien (1840–1889), Roman Catholic missionary to lepers on the island of Molokai in the Sandwich (Hawaiian) Islands, on his deathbed after contracting leprosy from the people to whom he ministered. Photo presumably taken by Dr. Sydney B. Swift on Palm Sunday, April 14, 1889, the day before Damien died/Alamy

British nurse Kate Marsden followed in Father Damien's heroic footsteps. From 1891 to 1892, she traveled across Siberia to Yakutia and established a leper colony in a village near Vilyuysk. Her work, like Father Damien's, was limited to caring for the sick rather than treating the disease. In 1895, Kate Marsden founded the St. Francis Leprosy Guild.

The Leprotic Rabbit

In the nineteenth century, an outbreak of leprosy was recorded in Norway. The same year that Father Damien began his missionary work in Hawaii, Norwegian scientist Gerhard Armauer Hansen published the results of his research. Hansen, a physician at St. Jørgen's Hospital in Bergen, which housed Norway's only leper asylum, was involved in testing various treatments: baths, ointments, and medications. However, none proved effective because the primary issue—the mechanism of disease transmission—was not understood. Most doctors still believed leprosy to be hereditary, as it often affected multiple members of the same family. However, Hansen proposed that an infectious agent was responsible. Tiny rods, later named Mycobacterium leprae, were found in the tissues of all leprosy patients. Hansen asserted that these rods were the causative agents of leprosy.

Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (29 July 1841 – 12 February 1912)/Wikimedia Commons

Now, Hansen needed to prove his hypothesis. He attempted to experimentally infect animals—rabbits and pigeons—but failed. ‘Have you ever seen a leprotic rabbit?’ the great German bacteriologist Robert Koch wrote to him in irritation. In response, Hansen tried to infect Kari Nilsdatter Spidsøn, one of the patients at St. Jørgen's Hospital, with leprosy. The woman was not informed about the purpose of the procedure, but she suspected that the hospital was conducting human trials. The case went to court, and Gerhard Hansen was subsequently banned from practicing medicine. At the end of the nineteenth century, when no one even considered asking for patients' consent for any sort of medical procedure, this was extraordinary—but the court ruled in favor of the plaintiff. Hansen was prohibited from engaging in medical practice. Thus, the precedent of ‘informed consent’ in medical research was established.

Deprived of the opportunity to practice, Hansen nevertheless continued his laboratory research. His place in history was secured by identifying the bacterium responsible for leprosy, Mycobacterium leprae. His findings that leprosy is an infectious, rather than hereditary, disease led to the adoption of a law in Norway in 1885 mandating the compulsory isolation of those with leprosy. Patients were now required to be quarantined either at home with a separate bedroom and their own utensils or in specialized institutions where all their movements were closely monitored. As a result, wealthier individuals who fell ill could remain at home, while the poor were effectively sentenced to life imprisonment.

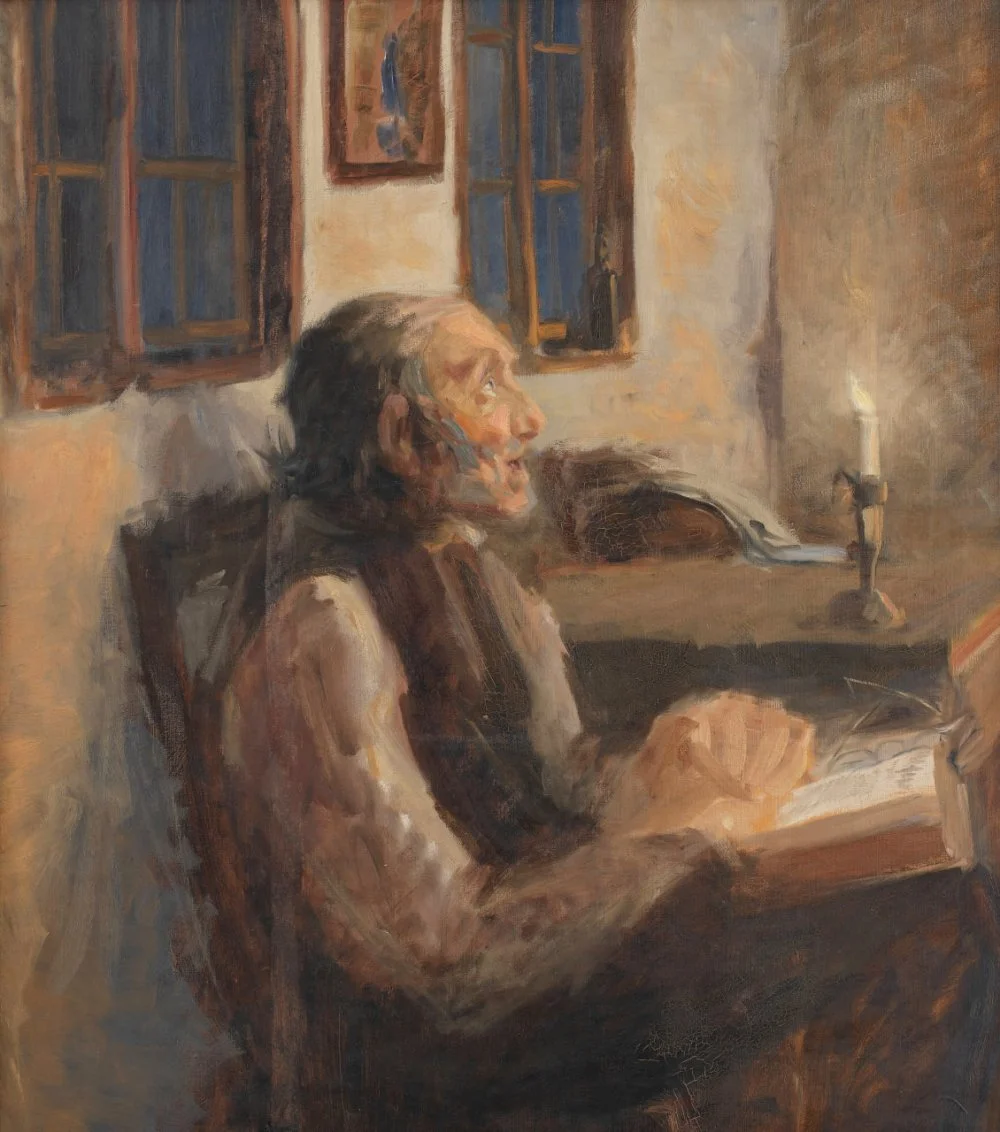

H. A. Brendekilde. The old man at the leper. 1896-1900/Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

The Departed

In 1931, Japan enacted a law mandating the compulsory isolation of all individuals with leprosy. The authorities exaggerated the risk of contagion, inciting widespread panic. Secret denunciations of suspected patients were encouraged, and they were forcibly sent to leper colonies, where they lived under harsh conditions with no hope of ever returning home. The patients were treated like prisoners and subjected to forced hard labor. Men were subjected to castration, and women to forced abortions to prevent the birth of children to those with the disease.

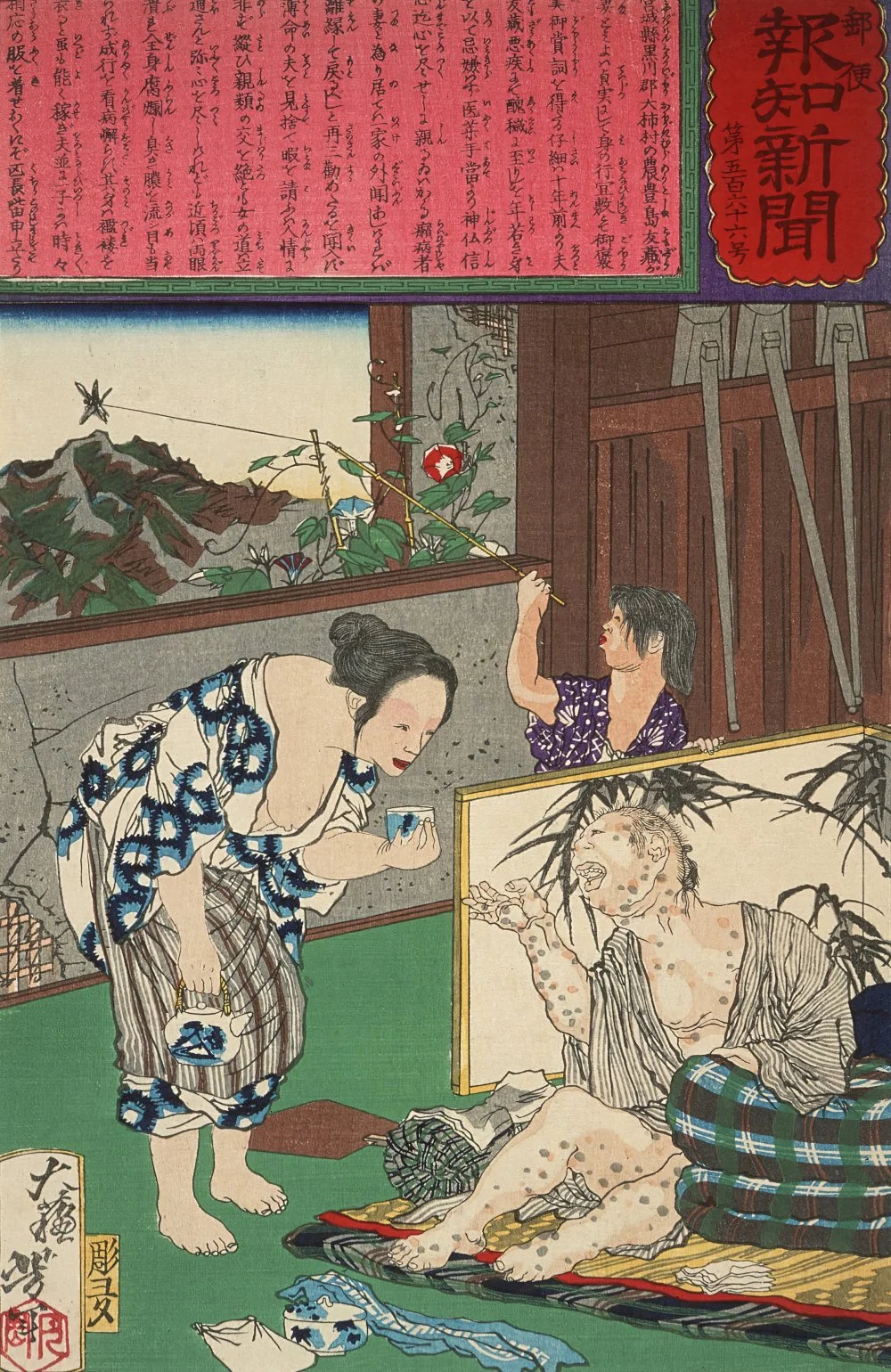

Toshima Tomiyo, who stayed with her leper husband, Tomozo, 1875. Creator: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi/Legion-Media

The house where a person with leprosy had lived was disinfected, causing the walls to turn white. This indicated to others that a person with leprosy had resided there. As a result, the families of those infected faced discrimination and ostracism. There were instances where relatives of the sick were forced into suicide, family suicides, divorces, job resignations, and separation from their families.

The policy of compulsory isolation continued for half a century, even after Hansen's disease became treatable. The Leprosy Prevention Act did not allow patients to leave the sanatorium, so even after recovery, many people could not return to their homes and families and had to remain in leper colonies for the rest of their lives. The law was abolished only in 1996.

Families of individuals with leprosy have filed lawsuits seeking compensation for the harm inflicted upon them. Most plaintiffs do not reveal their real names out of fear of discrimination. The remains of those who died from leprosy still rest in a common crypt and have not been returned to their families. It is evident that the ‘scars’ left by the state from forced isolation have not yet healed.

The Tomb of Tama Zenseen/www.nhdm.jp

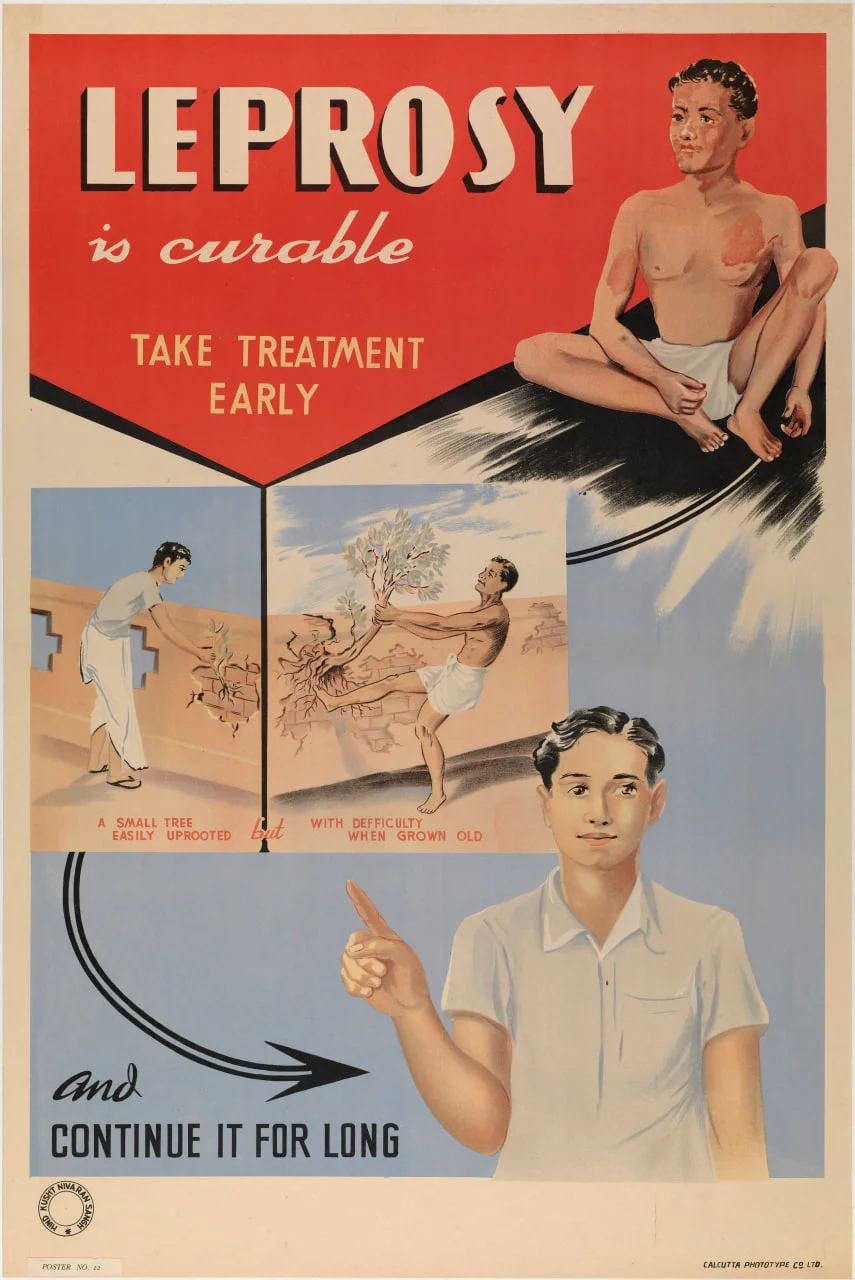

In recent decades, the incidence of leprosy worldwide has significantly decreased, especially after more effective medications became available in the 1960s. However, the disease remains widespread in several countries, and many who have been cured still face functional impairments and social stigma. Leprosy may be the first instance in history where a disease was considered the result of personal fault. This pattern is reminiscent of how society later viewed those with syphilis and, subsequently, the first generation of those with HIV, when the causes and mechanisms of transmission were unclear, but the mortality rate was starkly evident.

Leprosy: a patient uncured and a patient cured, the latter pointing to an allegory of early treatment. Colour lithograph/Wikimedia Commons

Bibliography:

Фуко М. История безумия в классическую эпоху М.: ACT: ACT МОСКВА, 2010

Стернз Дж. Заразные идеи. Тема инфекционных болезней в исламской и христианской мысли Западного Средиземноморья Средних веков и раннего Нового времени / пер. с англ. Д. Гальцина. СПб.: Academic Studies Press / БиблиоРоссика, 2024.

Немтина А. А. Святой Дамиан де Вестер. — М.: Издательство Францисканцев, 2014.

Brody S. N. The Disease of the Soul: Leprosy in Medieval Literature. Cornell University Press, 1974.

From Fiction:

А.К. Дойл 'Человек с побелевшим лицом'

Джек Лондон 'Кулау-прокажённый'

Пьер Буль «Загадочный святой»

Хорхе Луис Борхес. 'Хаким из Мерва, красильщик в маске'

Абрахам Вергезе. Завет воды

С.Моэм. Луна и грош