Arminius Vambéry, a Hungarian orientalist who traveled through Central Asia in the mid-nineteenth century, once remarked, ‘Revolutions (i.e., changes) that have taken place over hundreds, perhaps thousands of years, haven't had a significant change on the everyday life of the Kazakhs.’ The twentieth century, of course, brought radical transformations to the lives of Kazakh people that inevitably altered their way of life, necessitating a significant adjustment to Vambéry’s view. However, the Kazakh adherence to established traditions, rites, and customs survived social upheavals and remained an important part of their worldview. Thus, many traditions have come down to modern Kazakhs unchanged through the centuries, though others have evolved, and some have merged into a single ceremony.

Amongst the traditional rituals that have survived unchanged are those tied to the most significant events in a person's life, such as birth, marriage, and death. The first of these events, birth, is accompanied by perhaps the most archaic rituals.

The continuation of the family line is the most important responsibility of any tribe. The birth of a new life is celebrated as a mystery of existence, unmatched in its sacredness. It is no surprise then that from ancient times, this event has been accompanied by rituals of a mystical nature intended to preserve the life and health of the child and mother, to turn the child into a worthy member of the tribe, and to ensure a happy future life.

Many of the old traditions and customs associated with childbirth are still preserved among Kazakhs today, even in urbanized families in which children are born in hospitals. These rituals are especially retained among rural residents.

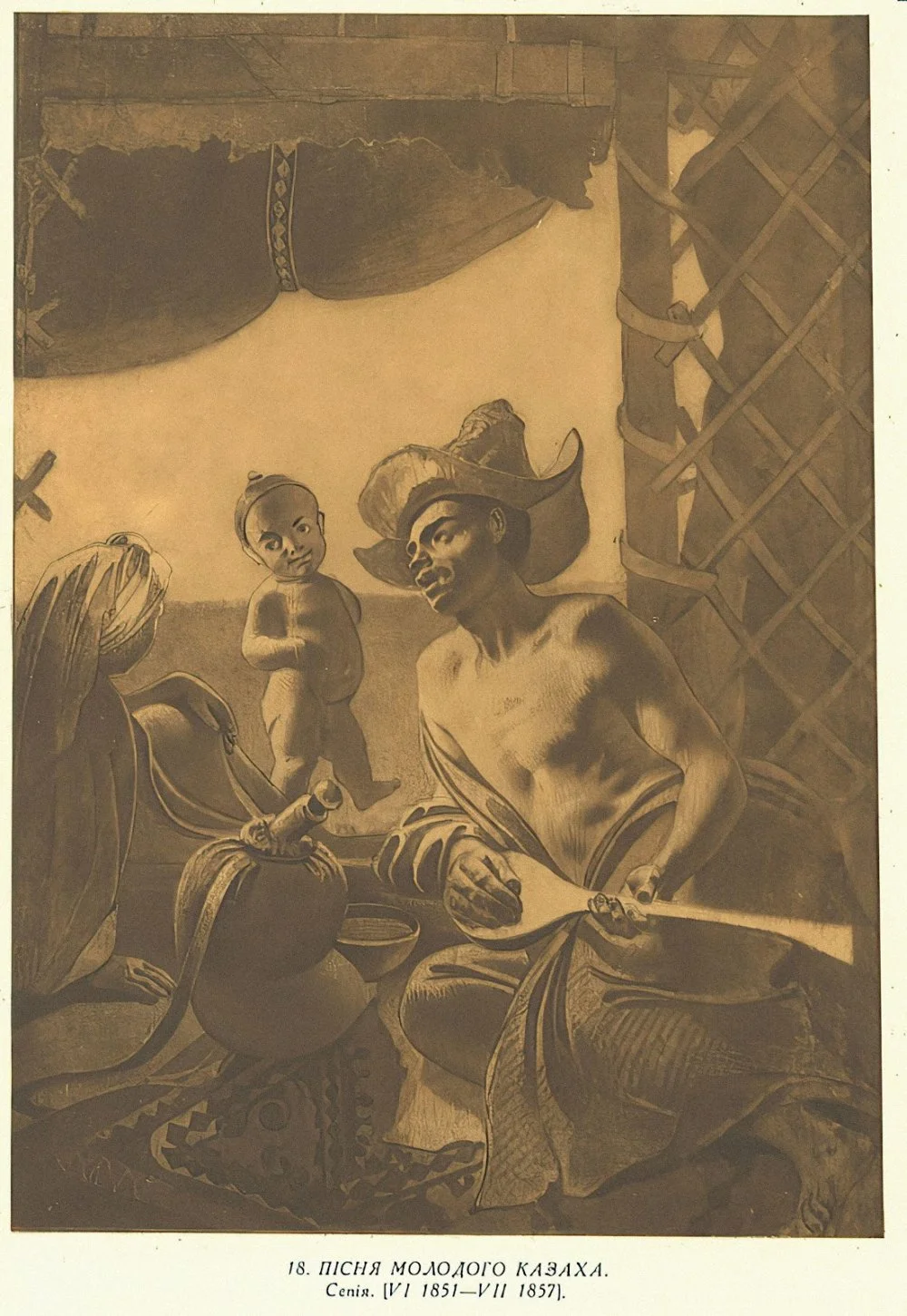

Taras Shevchenko. Young Kazakh Song. 1857/Alamy

Much depends on the mother's condition during labor, which is closely monitored by the older women of the household, and various ceremonies are followed to ensure an easy delivery. From the onset of labor, the mirrors in the house are covered, all vessels are filled with milk, all bags are untied, and the cupboards and chests are opened.

Meat, primarily liver (as it cooks quickly), is immediately put into a cauldron to encourage a swift birth. This custom is called qazan jarys (meaning ‘race with the cauldron’). Young women make noise by stomping their feet and banging objects on the ground, while men may beat drums—in earlier times, they would fire rifles. All this noise is meant to help the baby move more quickly toward being born. Curious young girls who come to observe the event have their dress hems torn off, which is said to both speed up the birth and distract the girls from interfering. Boys are usually sent away from the house during this time. And once the birth is over, the rituals surrounding the newborn begin.

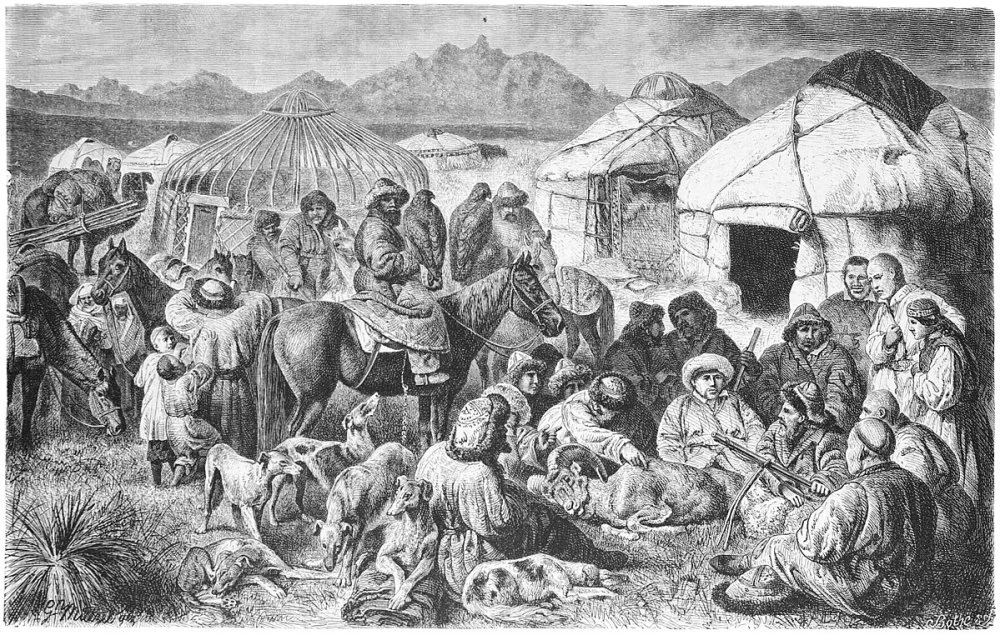

Gustav Mützel (German painter, 1839-1893). Yurt camp in the Kyrgyz steppe. Woodcut engraving. 1877/Wikimedia Commons

The first forty days of an infant’s life are considered the most crucial—this is a time when the baby’s bones and muscles get stronger. During this period, both the mother and the newborn are said to be particularly vulnerable to the ‘evil eye’, and they are protected from prying eyes, foul language, and unnecessary noise. To ensure that the child's growth is healthy, special attention is paid to the mother. Special food, known as bel köterer (meaning back lifting) is prepared for her. This primarily includes balamyq, a porridge made from roasted wheat and millet mixed with dried melon (a practice from the southern region), butter and milk. This porridge is believed to strengthen the mother's spine and benefit the child through her breast milk.

The süyindir (meaning ‘support’) ritual involves the arrival of the mother's parents, who have come to support their daughter, bringing a supply of food for the period until the child is forty days old. This food includes grains, qurt (dried cheese curds), butter, and cottage cheese. The jelek almashtyru (meaning ‘changing the scarf’) ritual involves the woman donning a special scarf that covers her chest during breastfeeding.

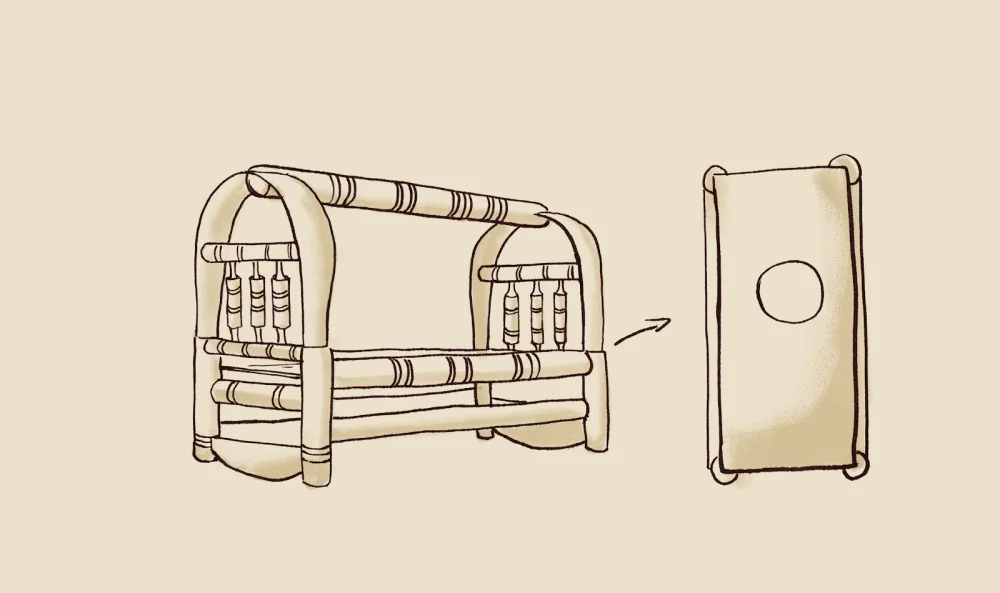

Besik/Qalam

The Kazakhs also place special importance on celebrating the shildekhana, the fortieth-day ritual, for the baby. Shilde means ‘forty’ in Persian and is a sacred number for the Kazakhs. In accordance with the traditional saying ‘You care for a son until he grows up, but for grandchildren until death’, this ritual is led by grandmothers, ensuring the transmission of life and spiritual experience across the generations.

The baby is bathed in salted water in a new, unused vessel—for the first forty days, the child is only washed in salted water, which is believed to benefit their health. Forty spoonfuls of water, each accompanied by a bata (blessing), are poured into the bath. Silver jewelry is placed in the bath—the primary purpose is for it to act as a talisman, though silver is also known for its disinfectant properties. The baby is bathed, with particular attention paid to washing the ears, groin, and armpits.

Picnic with family in traditional clothes singing in Saty pastureland on the Chilik river Kazakhstan/Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

After bathing, the baby’s chest is vigorously rubbed, causing droplets of colostrum (the first milk) to emerge from the baby's nipples as their body is still influenced by the mother's hormones. This colostrum is either rubbed into the child's scalp or collected on a cloth and stored. When placed in a glass of water later, the cloth is believed to turn the water into a healing drink. Bathing, trimming the baby's nails, and shaving their head are entrusted to honored guests with experience as mothers.

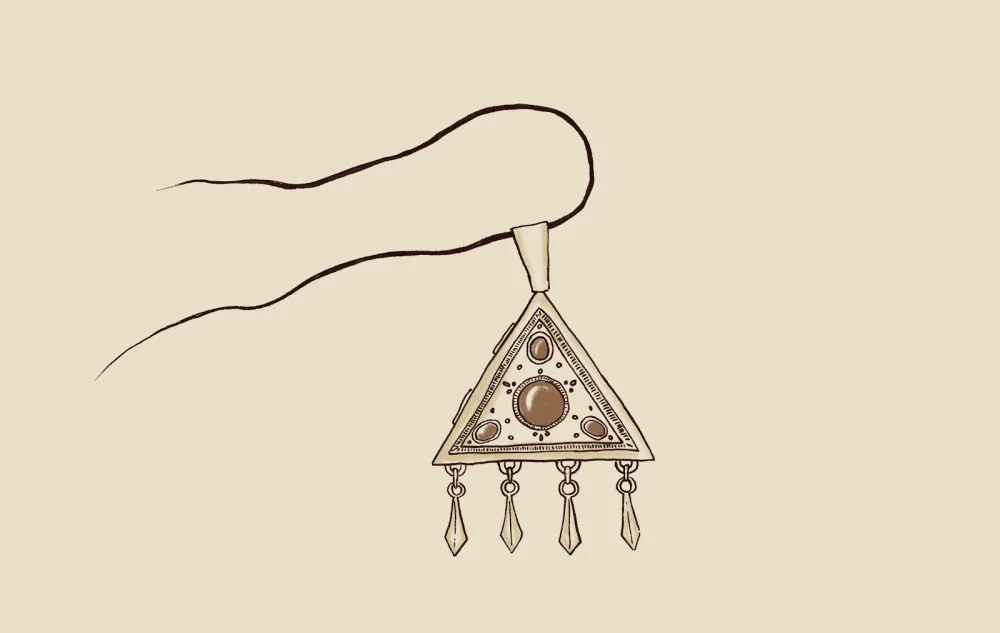

The nails are buried under a tree, and the hair is placed in an amulet called a tūmar. Afterwards, silver jewelry is gifted to the women who participated in the ritual. Of course, the event concludes with a grand feast featuring food, music, and entertainment.

The scale of the celebration depends on the family's resources—sometimes all the residents of nearby villages are invited, with hundreds of guests attending. Competitions between aqyns (poets) and şabandozdyq (demonstrations of horse-riding skills) are popular celebratory activities.

Tumar/Qalam

On the fortieth day, the baby is also given a name. Kazakhs do not choose names based on how fashionable or popular they are; instead, they focus on the meaning and associations of a name. For instance, children are often named after a revered local figure like a legendary batyr (warrior) or a famous historical, cultural, or literary figure. It is believed that by sharing the name of a great person, the child may inherit some of their talents.

There have even been cases where a child was given a deliberately offensive or humiliating name as it was thought such a name would provide strong protection against the evil eye. Another form of protection was naming the child after the first object the mother saw after the child was born. Though such names are becoming more rare today, the older generations still have seemingly odd names like Baltabay or Balgabay (balta meaning ‘axe’, and balğa meaning hammer).

Once a name is chosen, it is shouted into the newborn’s right ear, with this responsibility typically falling to the most honored guest, usually an imam. After this, the new Kazakh, even though they are still a baby, is no longer considered a mere visitor to this world but a full-fledged member of the family and tribe.