Amir Timur is one of the most famous conquerors in history, and as befits the way he lived, he has a controversial legacy. To some, he is a great statesman, a pious Muslim, and a city builder; to others, he is a brutal barbarian. Here in Central Asia, Timur’s greatness is not generally disputed—on the contrary, many people see him as a great ancestor. His ability to unite large territories and be a champion of culture and religion has contributed to his status in the region, even leading many to consider his reign a golden age. Given this dual reputation, Qalam has tried to explore the most important questions about Timur’s personality and legacy.

- 1. Why is Timur important?

- 2. When and how did Timur rise to power?

- 3. Who were the Barlas?

- 4. What did Timur look like?

- 5. Was Timur really as cruel as he was sometimes painted?

- 6. Was Timur a nomad?

- 7. Why is the name ‘Tamerlane’ an insult?

- 8. Was Timur a devout Muslim?

- 9. How many languages did Timur speak, and what was his native language?

- 10. Was Timur Chinggis Khan’s successor?

- 11. So, can Timur be considered Uzbek? Could he have been Kazakh or Kyrgyz?

Why is Timur important?

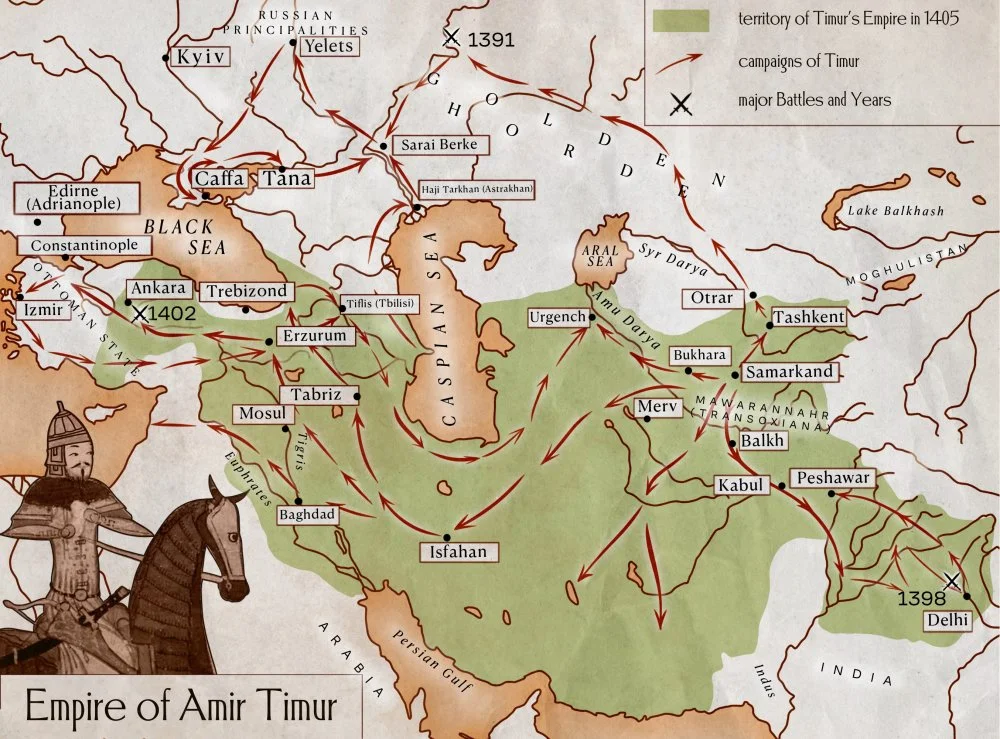

Timur was the creator of a vast empire that spanned parts of ancient Mesopotamia and what is now Afghanistan, Iran, northern India, and Central Asia. He was the founder of the Timurid dynasty, and he left behind a colossal cultural heritage, especially in art and architecture.

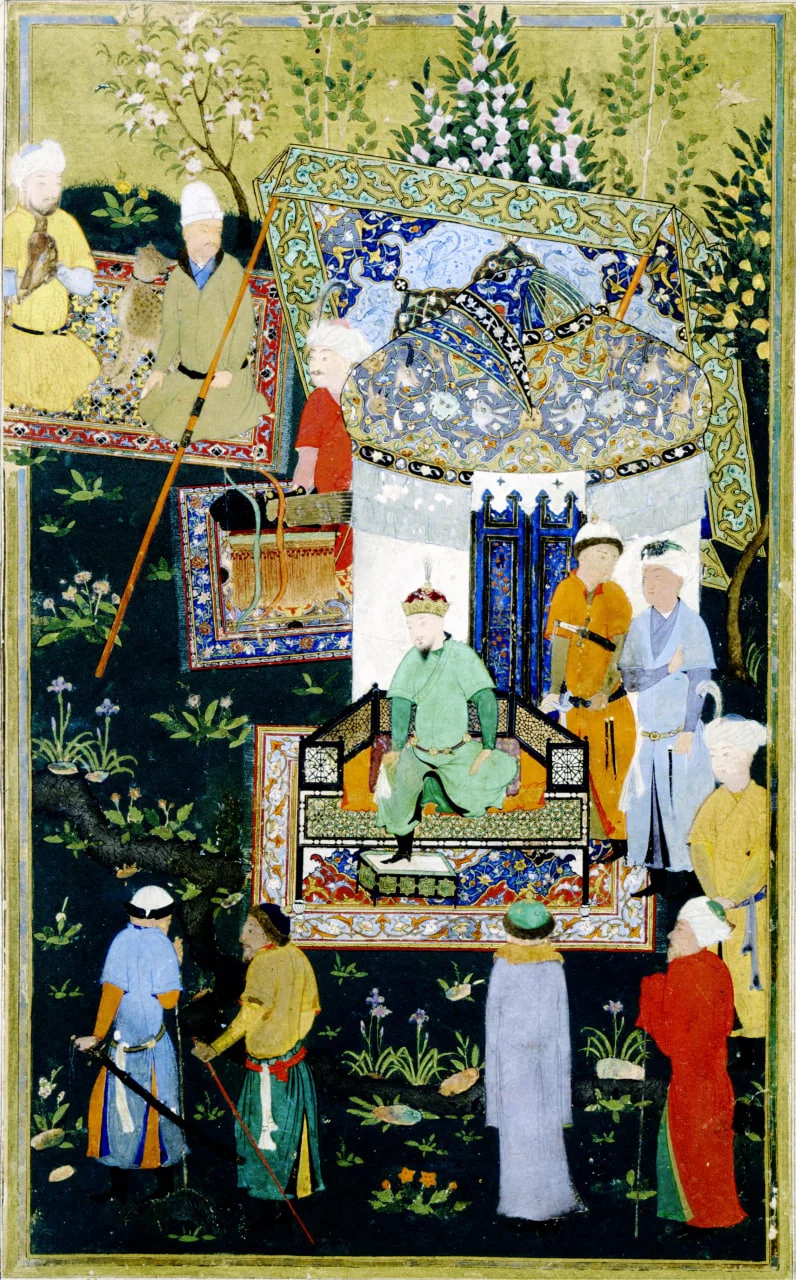

Timur in an Indian miniature. Late 18th century/ National Library of France, Department of Manuscripts, Eastern Division/Wikimedia Commons

Timur became a hero in the folklore of many Turkic peoples, often appearing in stories and parables, such as those about Nasreddin Hodja. In addition, Timur’s tomb, located in Samarkand, became even more famous when it was opened by Soviet scientists on the eve of the Great Patriotic War. The structure is shrouded in legends of a terrible curse, being inscribed with two warnings about disturbing the great emir’s rest, which have added an air of mystery to his story.

In Uzbekistan, Timur is honored as a national hero and a symbol of pride. However, the theory that Timur may have been Kazakh or Kyrgyz has recently gained popularity. Proponents of this strange hypothesis often deny Timur’s Mongol roots, claiming that the Mongols are a fictitious nation. These are also the same people who speak of the Turkic (often Kazakh) origin of Chinggis Khan.

Timur also left his mark on the history of India, with his descendants, the Mughals, ruling India until the nineteenth century. However, Timur is not considered a Hindu figure in India as he was a devout Muslim who left a legacy tied to Islamic customs and culture. In the current time, there has been a growing tendency to downplay the Muslim heritage and the contribution they made, to the extent of removing mention of them from school textbooks.

When and how did Timur rise to power?

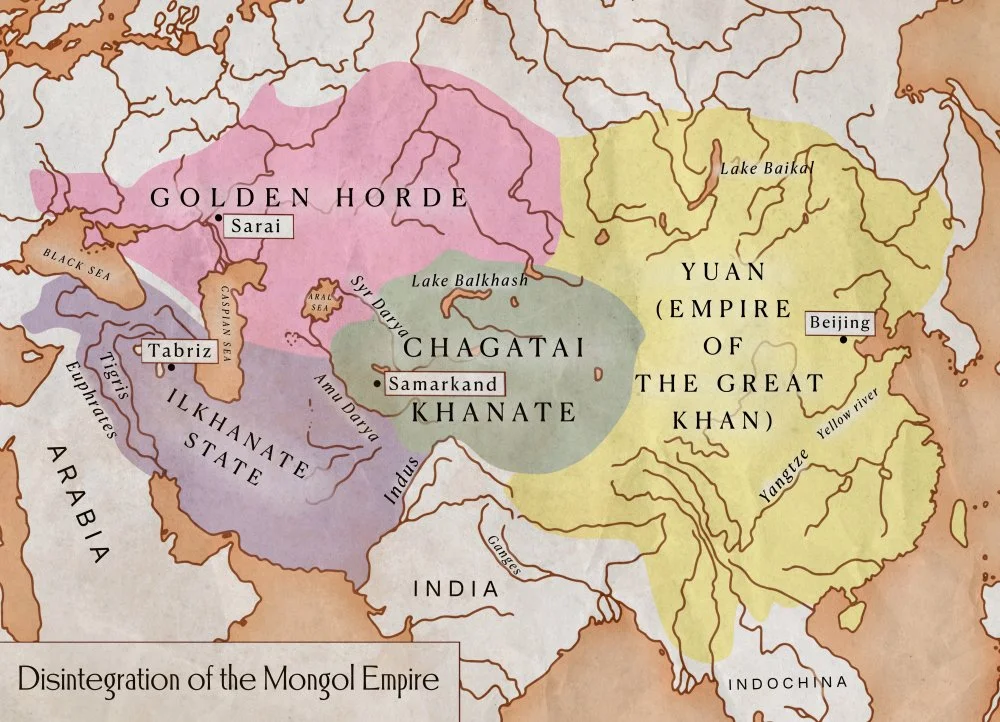

Timur was born on 9 April 1336, in Transoxania, in the village of Khoja-Ilgar near the city of Kesh (now Shahrisabz, Uzbekistan) in Central Asia. Timur spent his childhood and youth in the mountains of Kesh. In the fourteenth century, Central Asia was the territory of the Chagatai Ulus (appanage) of the Turkic-Mongolian state that emerged from the collapse of Chinggis Khan’s empire.

This state was named after Chinggis Khan’s son Chagatai (1224–42). In the fourteenth century, the power of the Great Khan’s heirs gradually weakened in many uluses, and many conflicts broke out at the same time. This affected both the Golden Horde (Ulus of Jochi) and the Chagatai Ulus, which split into two entities in 1347: Mavarannahr and Moghulistan.

As a result of the disputes, power in these areas began to shift to local military leaders called emirs, and Timur was one such emir from the Barlas tribe. He emerged as the most successful in this struggle for power, and in 1370 he established himself as the ruler of Mavarannahr. After that, he devoted all his political and military efforts first to the restoration of the Chagatai Ulus’ territory and then to its expansion. Timur made Samarkand the capital of his empire, and after his death in 1405, his empire began to gradually disintegrate again.

Who were the Barlas?

The Barlas were originally a nomadic Mongolian tribe, who played an important role in Chinggis Khan’s campaigns. For example, one of his closest aides, Khubilai (not to be confused with Kublai Khan, Genghis Khan’s grandson), was a Barlas. At first, the Barlas lived in the territory of modern Mongolia, but they gradually migrated to Central Asia, which was inhabited by Turkic peoples. Apparently, most of the Barlas moved there with Chinggis Khan’s son Chagatai, whose ulus was located in this region. Here, the Barlas settled in the Kashkadarya oasis, accepted Islam, and quickly became Turkicized, that is, they began to speak the Turkic language. By the middle of the fourteenth century, it is likely that the Barlas had largely forgotten the Mongolian language, but they retained some Mongolian nomadic traditions and customs.

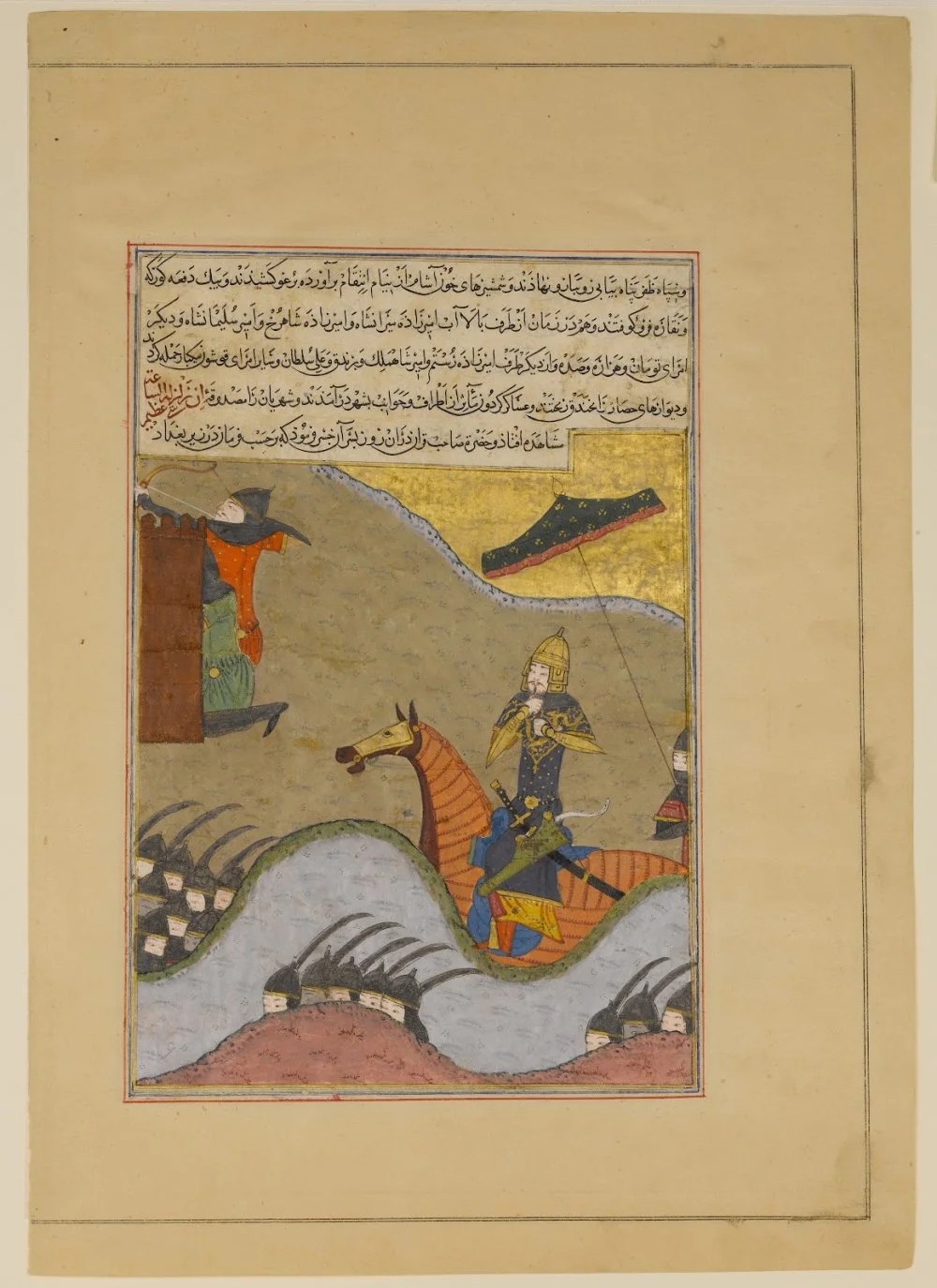

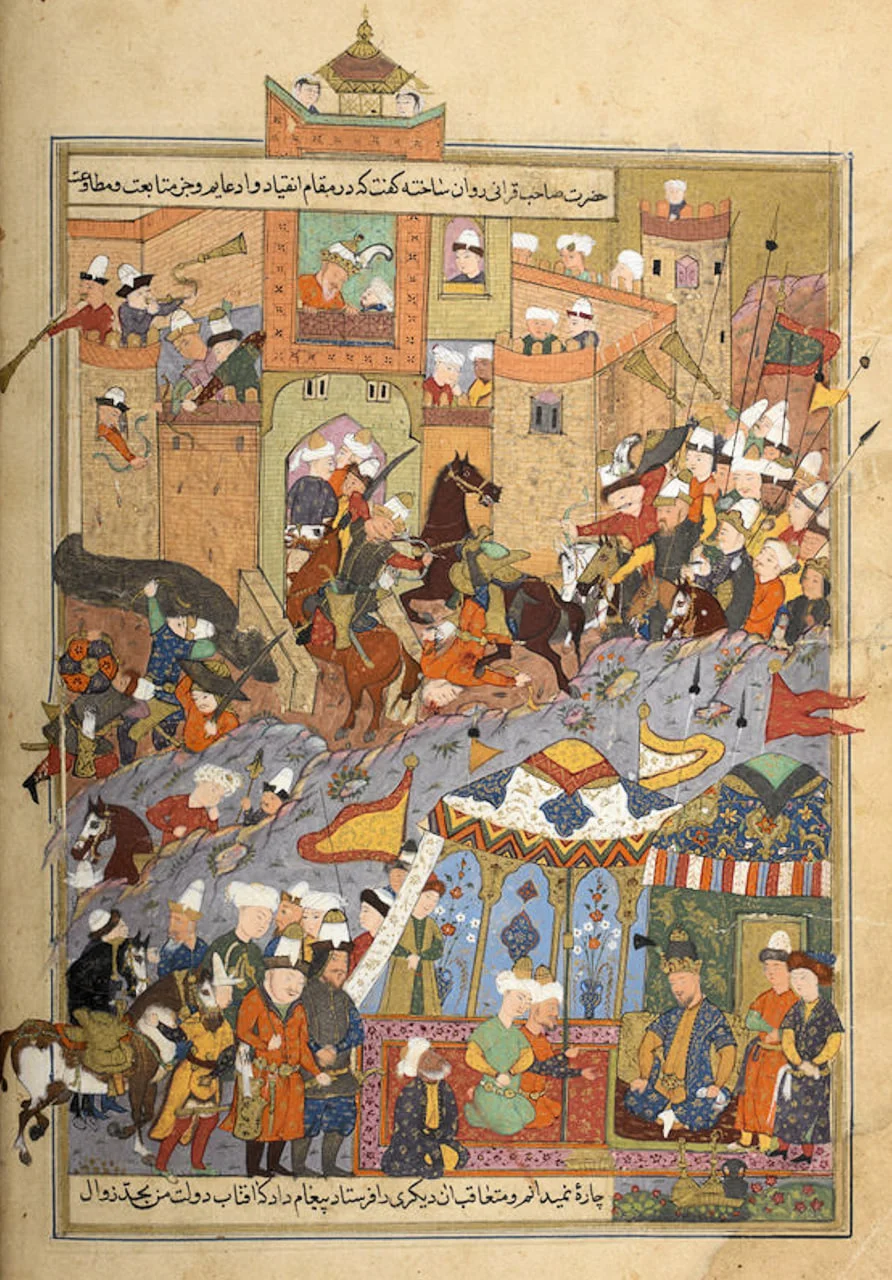

Conquest of Baghdad by Timur, Folio from a Zafarnama (Book of Victories). 15th century/Wikimedia commons

What did Timur look like?

In June 1941, Timur’s tomb in the Gur-e-Amir mausoleum in Samarkand was opened. Under the direction of the Soviet anthropologist Mikhail Gerasimov, the remains of Timur and several of his heirs were examined, and then an attempt was made to reconstruct his appearance.

Standing at 170 centimeters, Timur was quite tall for his time. He had long hair of a reddish hue, wore a mustache, and his features were Asian. Gerasimov claimed that Timur belonged to the so-called South Siberian race, which was a transitional race between Asian and European.

Timur’s facial reconstruction/Wikimedia commons

Was Timur really as cruel as he was sometimes painted?

In many historical works from Timur’s time, one can find descriptions of the various atrocities committed by his army. During one campaign, Timur ordered 100,000 prisoners to be killed. During another, he ordered towers decorated with 70,000 thousand heads to be erected to serve as a warning to future rebels. It is difficult to confirm (or refute) these numbers, but Timur’s notoriety is most likely the result of propaganda, both his own and that of his opponents.

The Apotheosis of War by V.V. Vereshchagin. 1871/Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow/Wikimedia commons

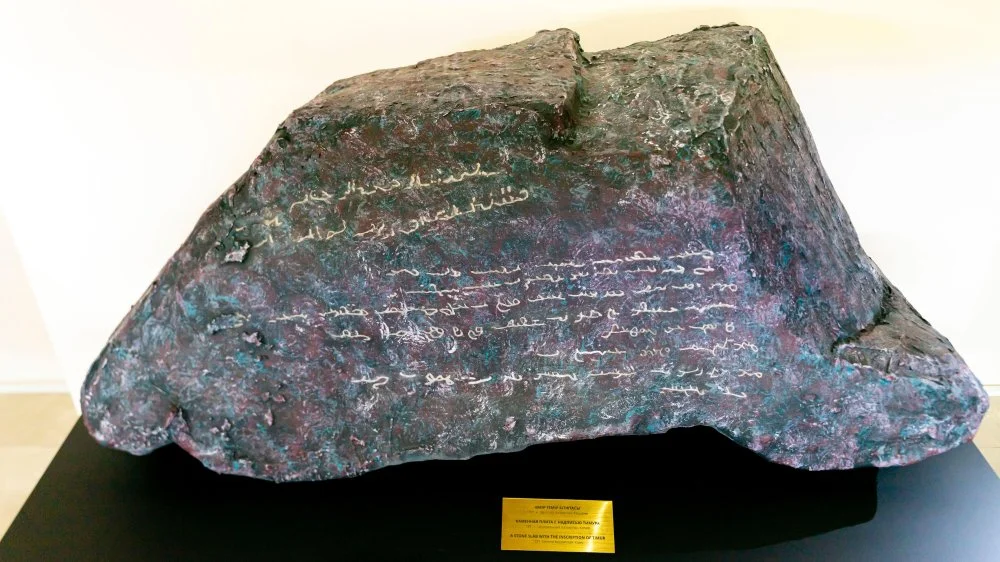

To kill such a large number of people, especially very quickly, you’d need a very large army, many times larger than the number of victims. In 1391, during the war with the khan of the Golden Horde Tokhtamysh, Timur had an inscription carved on a stone plaque in Samarkand, claiming that the size of Timur’s army was 300,000. Obviously, this was a gross exaggeration. And thus, the number of casualties (though certainly large for those times) was much smaller.

Was Timur a nomad?

Timur began his career as the leader of a band of nomads, and all the evidence suggests that he grew up in a shepherd environment. However, this environment was different from that of his great predecessor, Chinggis Khan. Mavarannahr, where Timur grew up, was a region with a large number of cities and ancient agricultural traditions. In addition, Shahrisabz, the city near which Timur was born, was ruled by the Barlas at the same time. This means that the future emir was well acquainted with both urban and rural life.

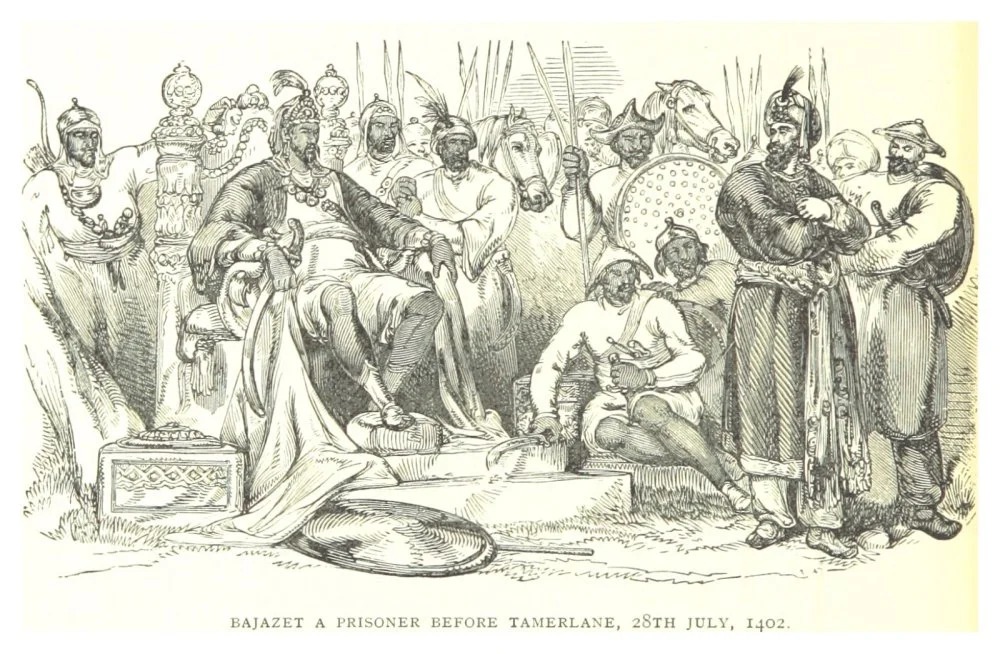

Осман сұлтаны Баязид Темірдің тұтқынына түсуі (1402). 19 ғасырдың соңында жасалған сурет/Wikimedia Commons

Almost all medieval pictures of Timur show him sitting by a tent, a classic attribute of a nomadic commander. But in his peaceful life, after becoming emir, he resided within the city walls, in his palace. In this, he was not unique. As early as the thirteenth century, Chagatai nobility was divided over the transition to urban life. In 1269, at the Kurultai (the congress of the Mongolian nobility), the khans agreed to live in the mountains and steppes and not in the cities. Those who remained in Mavarannahr and violated the Kurultai’s resolution were called ‘karunas’ by the Chagatais of the steppe, meaning mongrels or impure Mongols. Strangely enough, Timur’s conquests were mainly focused on urban civilizations: China, Persia, and India. Having defeated Tokhtamysh, for example, Timur was not particularly interested in the steppes of the Golden Horde.

Timur granting audience on the occasion of his accession, from Zafarnama, or Book of Victory, this 15th century Persian manuscript features illustrations by the renowned painter Bihzad, 1467/Photo by JHU Sheridan Libraries/Gado/Getty Images

Why is the name ‘Tamerlane’ an insult?

Timur is known as ‘Tamerlane’ in all European languages, which comes from the Persian nickname ‘Temūr(-i) lang’ which means ‘Timur the Lame’. Timur acquired a limp during a battle at the beginning of his military and political career. He was wounded by an arrow in the leg and lost two fingers on his right hand.

Timur at the siege of the fortress of Balkh in 1370. Miniature from the Persian Chronicle. 1599/British library/Wikimedia commons

The nickname also has a Turkic version: ‘Aksak Temir’. Interestingly, in these cultures, Timur was also called ‘Iron Lame Man’, which is a literal translation of his name. Timur became so closely associated with his physical ailment that it sometimes seems as if he proudly wore his ‘title’ of a lame man. But this is not the case. First, Timur does not refer to himself as such in any official documents or letters. Second, in various historical sources, Timur’s opponents mostly attributed his particular cruelty with his limp. Persia was one of Timur’s first victims outside Central Asia, and the Persians hated him with a vengeance, using the nickname as an insult.

Was Timur a devout Muslim?

Timur took great care to maintain his reputation as a devout Muslim, calling himself the ‘Sword of Islam’. All his conquests were carried out under the banner of protecting Muslims and punishing infidels. Indeed, the cultural heritage of Timur’s empire certainly belongs to the world of Islam. And yet, scholars often question how consistent a Muslim Timur was. For example, was he a Sunni or a Shia (these are the two main streams of Islam; most Muslims today identify as Sunni)?

Formally, most of the evidence points to the first option: Mavarannahr was predominantly populated by Sunnis, Timur patronized Sunni Sufi orders, and he fought against Shia rulers. And yet, there were Shia generals in his army

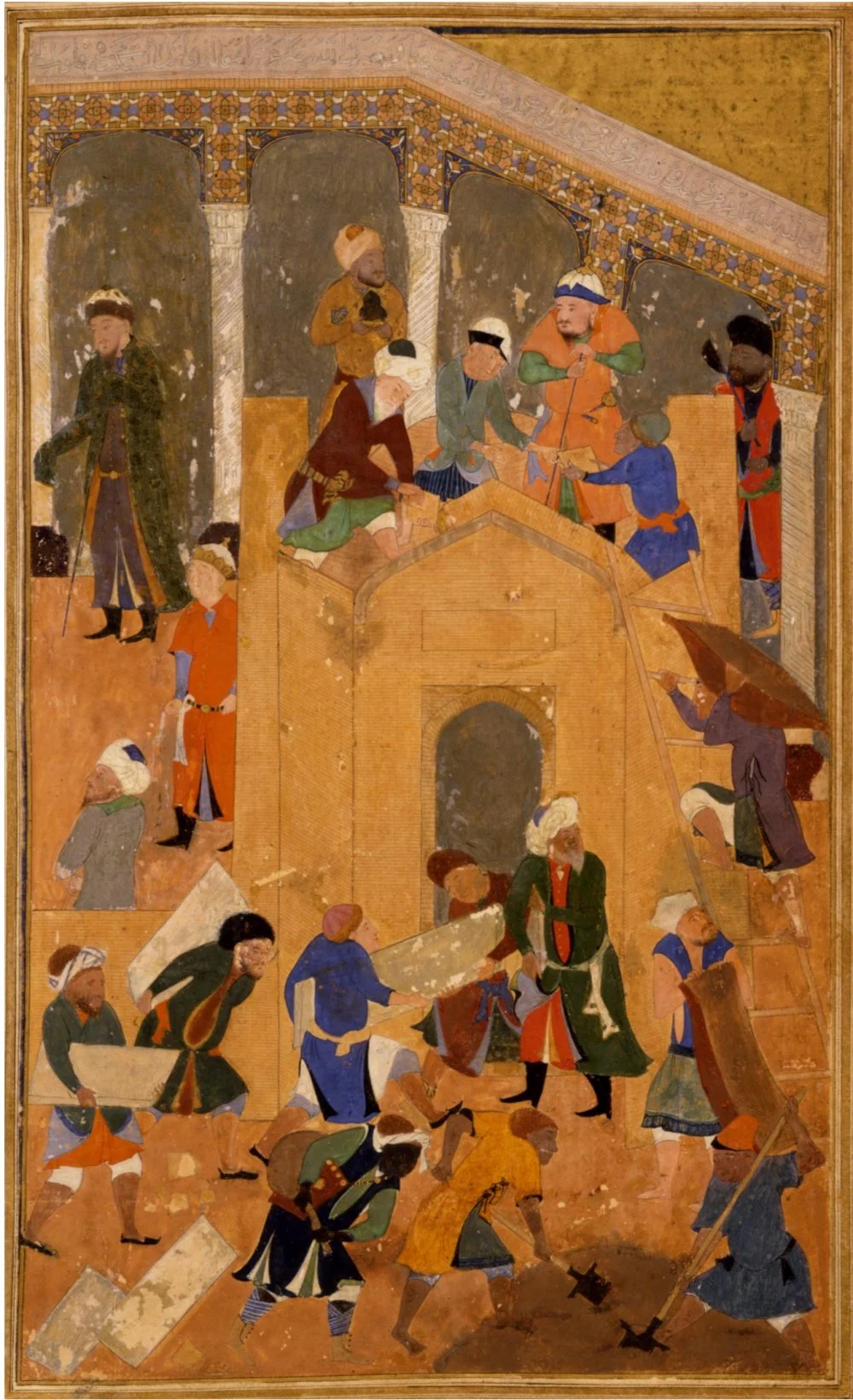

Building of the Great Mosque in Samarkand. Creation date: 1467-1468, creation date: illumination, ca. 1480s. Author: text by Sharaf al-Din ’Ali Yazdi (Islamic, died 1454) Painter: illustrations by Bihzad (Persian, 1450-1536)/John Work Garrett Library Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Timur’s tomb includes an inscription that traces his lineage to Caliph Ali, who was a key figure for the Shia. All this leads some scholars to say that Timur was a Shia or ‘pro-Shia’ ruler. Most likely, as was often the case with rulers, Timur’s attitude toward religion was purely instrumental. He needed to justify his own power, and in the Middle Ages, one of the important aspects of legitimation was religious. Moreover, all high culture (literature, architecture, painting, and much more) was concentrated in the religious sphere, and therefore Timur, as the leader of the empire, aspired to be a part of that world. In everyday life, though, he was hardly religious.

High angle view of a mausoleum, Gur Emir Mausoleum, Samarkand, Uzbekistan/Photo by DEA / C. SAPPA/De Agostini via Getty Images

A European traveler who visited Timur’s court in Samarkand reported that the emir and his entourage drank wine, and to get drunk in Timur’s presence was a valiant act, and such a person deserved the reputation of a ‘bahadur’ or a ‘hero’.

In all likelihood, Timur’s religious ideas included Mongolian shamanistic elements that had not yet disappeared from practice.

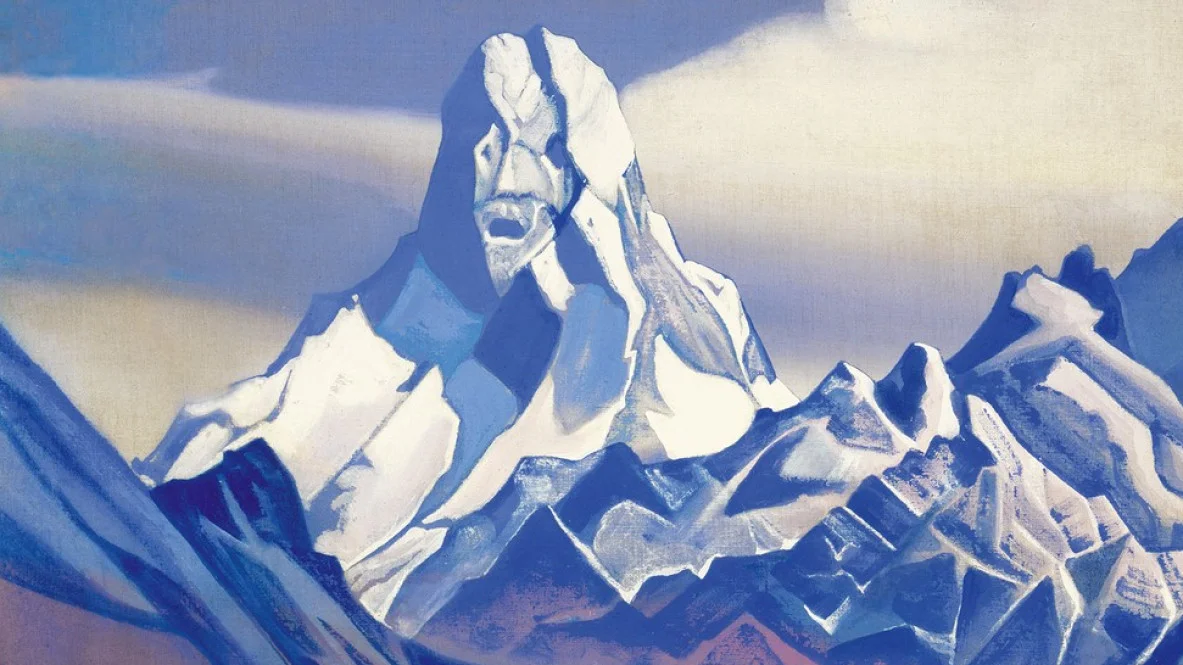

In Kazakhstan today, there is a mountain called Ulytau, and in 1391, during a military campaign against the Golden Horde, Timur ordered a camp to be set up and to carve an inscription on a stone on this mountain.

In addition to the inscription, a mound and a place for a bonfire were established there by Timur’s troops. It is known that the worship of the mountain was part of the Mongolian shamanistic ancestor worship, which was maintained by many nomads despite the adoption of Islam. Timur was a warrior, and warriors in many cultures have the strongest attachment to pagan symbols.

How many languages did Timur speak, and what was his native language?

According to the medieval chronicler Ibn Arabshah, who was imprisoned by Timur, the emir was fluent in Turkic, Mongolian, and Persian. Most state documents were written in Chagatai (a literary version of Turkic), Turkic, and Persian. As for Mongolian, different scholars have different views. Some believe that Timur barely knew Mongolian, others that he could speak it, though not very fluently. Timur must have understood Arabic at least at a basic level, because Islamic culture is essentially based on the Arabic language.

Stone slab with the inscription of Timur Tamerlan, 1391, Central Kazakhstan, a copy, National Museum of Kazakhstan, Nur-Sultan/Alamy

It is important to note that Timur himself did not write letters and documents—he was illiterate. He had a large staff of scribes and translators, who were needed for diplomatic correspondence and the issuance of decrees to manage the multinational empire and interact with its neighbors. The Turkic peoples living in this area spoke different dialects that had not yet evolved into separate languages. Linguists unite these dialects into the Middle Turkic language, variations of which have come down to us in the form of various written monuments. All speakers of these dialects had to understand each other without interpreters, and Timur was certainly no exception.

Was Timur Chinggis Khan’s successor?

In a political sense, Timur ‘revived’ Chinggis Khan’s empire. Almost all of his military campaigns were justified by his drive to restore the legitimate Mongol heritage. Formally, his state was headed by puppet Chinggisid khans (that is, direct descendants of Chinggis Khan), and he himself assumed the ‘modest’ title of Grand Emir. Timur sought to intermarry with the Chinggisid by marrying the daughter of a Chinggisid khan and receiving the title of son-in-law (guragan) of the khan.

Antiquities of Samarkand. Palace of the Bukharan Emirs, "Kok Tash." Throne of the Emir Kok Tash in the Reception Hall/Wikimedia commons

He drew up an official genealogy, according to which he had a common ancestor with Chinggis Khan. In many other matters, the Great Emir relied on Mongolian political traditions. For example, the decimal structure of his army was the same as the traditional organization of Chinggis Khan’s army. In the Turkic-Mongol world, the Great Khan’s empire was as much a political reference point as the Roman Empire was in the Western European world.

So, can Timur be considered Uzbek? Could he have been Kazakh or Kyrgyz?

Well, the right answer is neither as modern nations did not form until much later. In Timur’s time, the boundaries between languages, tribes, and even faiths were extremely fluid. To answer the question of Timur’s ethno-religious affiliation, it would be correct to consider not who modern scholars think he was, but who he himself thought he was. This question is answered by his actions. He was a Turkic-Mongol conqueror, a Muslim who retained traces of Mongolian shamanism, an urbanized nomad who, like many of his tribesmen, spoke several languages but knew Turkic best.

Politically, he adopted both the Mongolian traditions established by Chinggis Khan and the Persian traditions, at least in terms of the bureaucratic structure of the state. But inevitably, both in terms of his birthplace and burial place, and in terms of his cultural and architectural heritage, it was the territory of modern Uzbekistan that remained the cradle of his empire, and he would later become the most important element in the consolidation of the Uzbek nation.

UZBEKISTAN - JANUARY 11: The monument dedicated to the Uzbek warlord Tamerlane in the central square of Shakhrisabz, Uzbekistan/Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images