During the Second World War, millions of Soviet soldiers were taken prisoner by the Nazis, and among them were thousands from Kazakhstan. However, by refusing to sign the Geneva Convention, the Soviet Union stripped its captured soldiers of the right to humane treatment. After the war, these individuals were erased from the official narrative—both in public memory and the archives. It is only now, thanks to new research and declassified documents, that we are beginning to learn the tragic truth of their fates.

The Tragedy and Stigma of Soviet Prisoners of War

For a long time, the subject of Soviet prisoners of war (POWs) remained classified and was deliberately silenced at various levels of Soviet society. Soviet historiography focussed on only the heroism soldiers showed in Nazi camps, while those who were taken captive were automatically categorized as ‘traitors’ and ‘enemies of the people’—a stigma that followed them both during the war and long after the war.

In contrast, Western historians, especially in Germany, began to actively study the fates of Soviet POWs much earlier. A particularly noteworthy study is a monograph by Christian Streit, which is based on extensive documentary evidence of the inhumane crimes committed in Nazi campsi

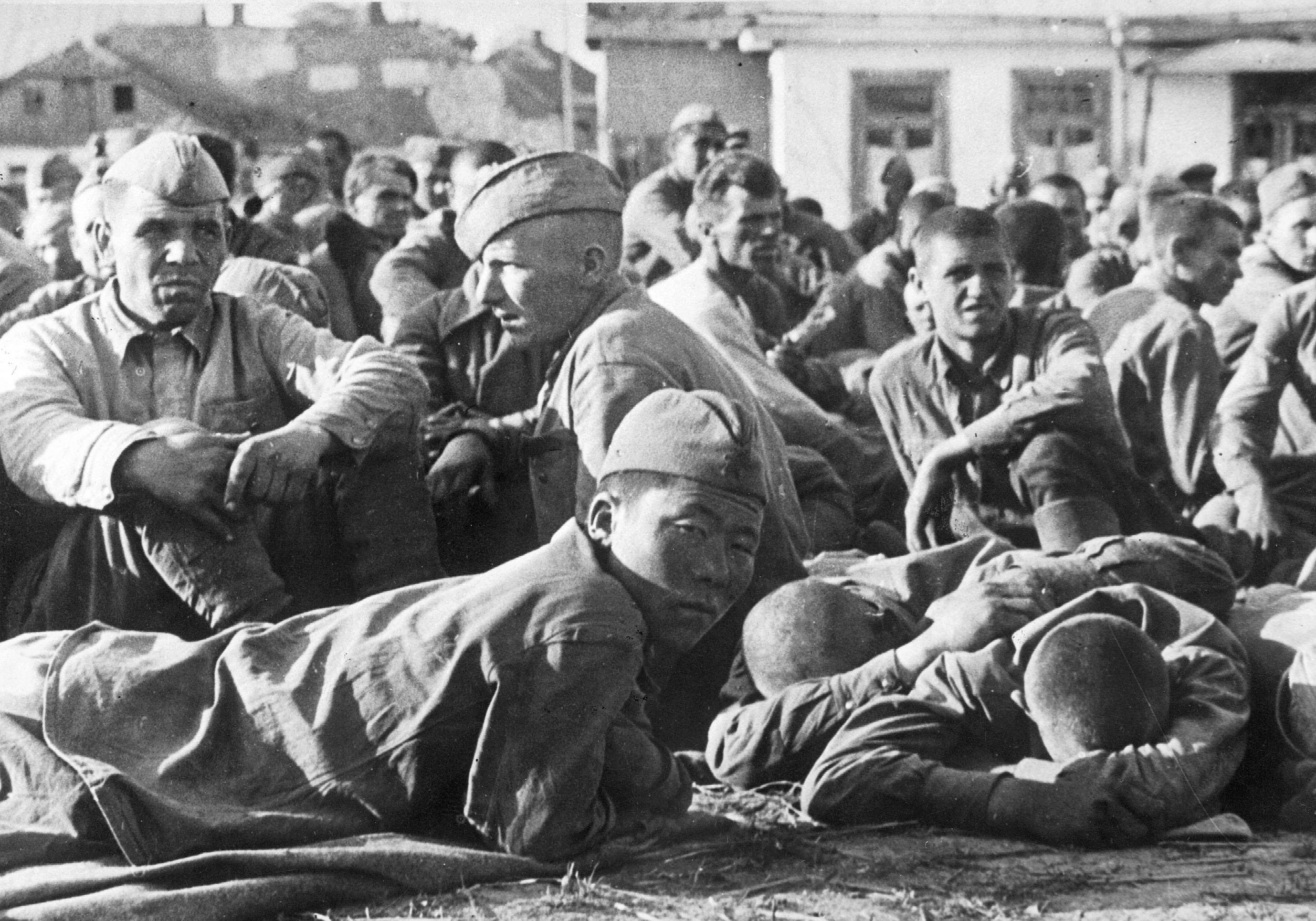

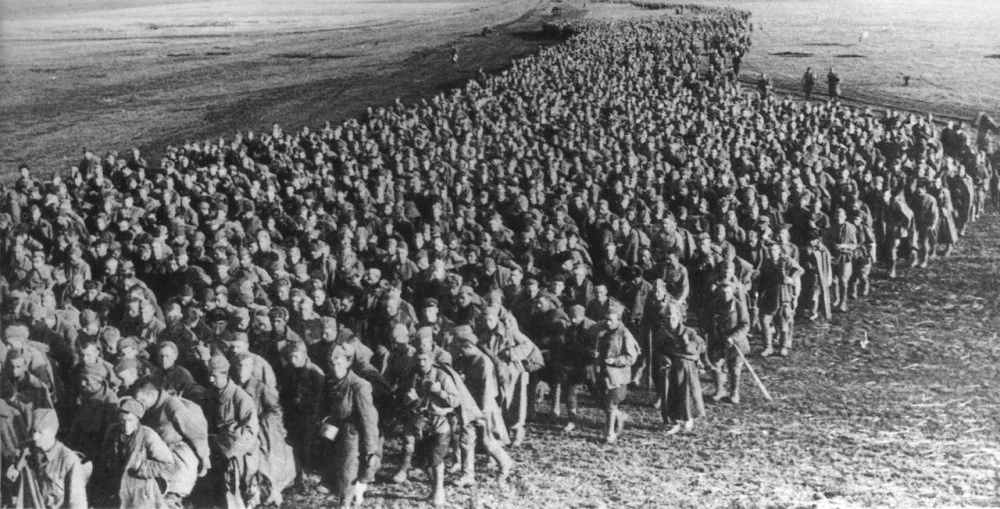

Soviet prisoners in a concentration camp, Russia, World War II. From L'Illustrazione Italiana, No. 40. October 4, 1942 / DE AGOSTINI PICTURE LIBRARY / Getty Images

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, German and Russian scholars began to move beyond the ideological stereotypes of the Cold War era and adopted an objective, scientific approachi

Yet, amid this growing body of research, the fate of the Kazakh POWs was largely ignored in these studies—in fact, in many of these studies, they weren’t mentioned at all. Meanwhile, much of Kazakhstan’s historical scholarship has largely focused on the conditions experienced by German and Japanese POWs in camps located on Kazakh territory, rather than on Kazakh soldiers taken captive abroad.

Only in recent years have scholars begun to explore this long-neglected subject; new monographsi

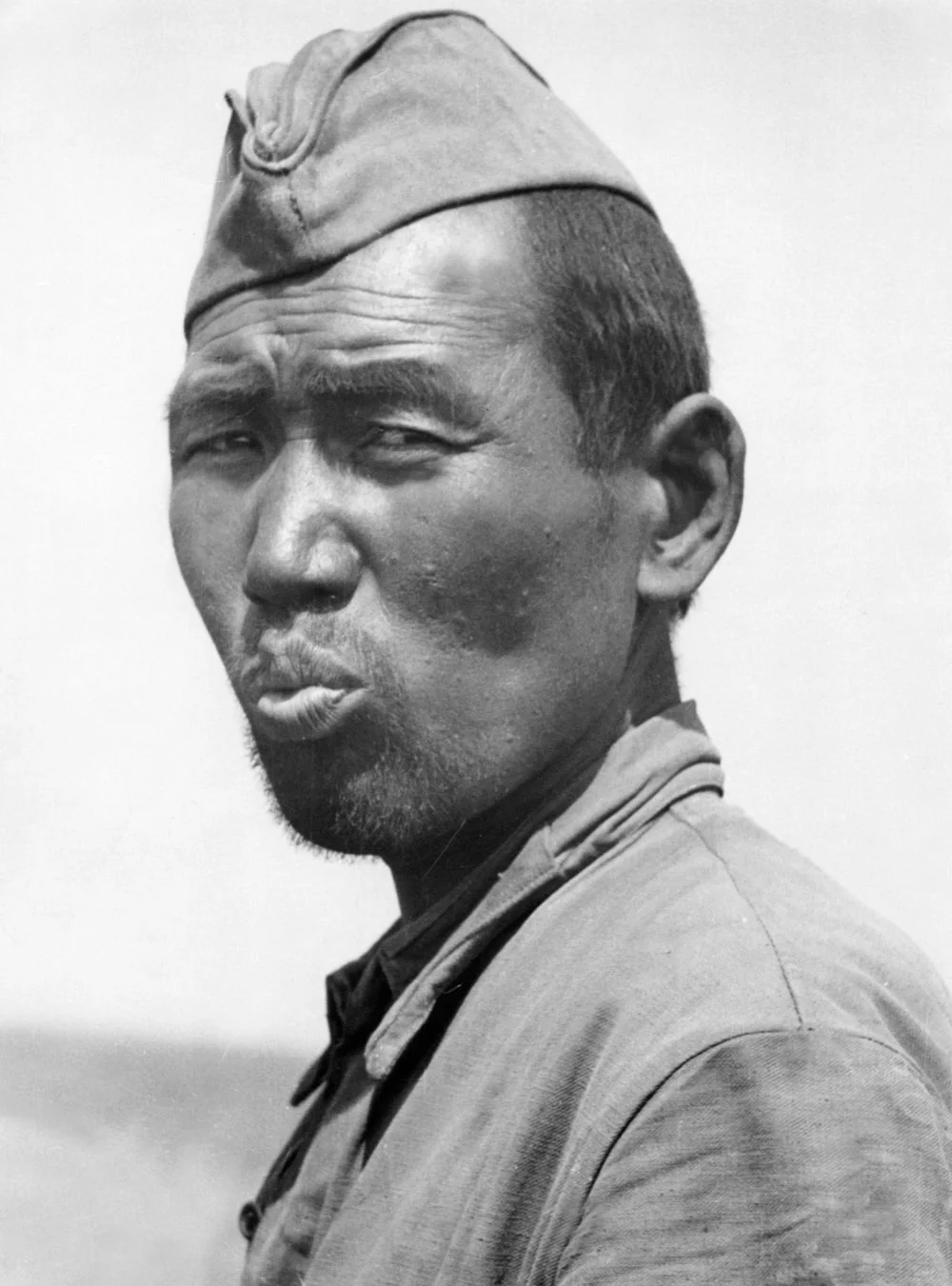

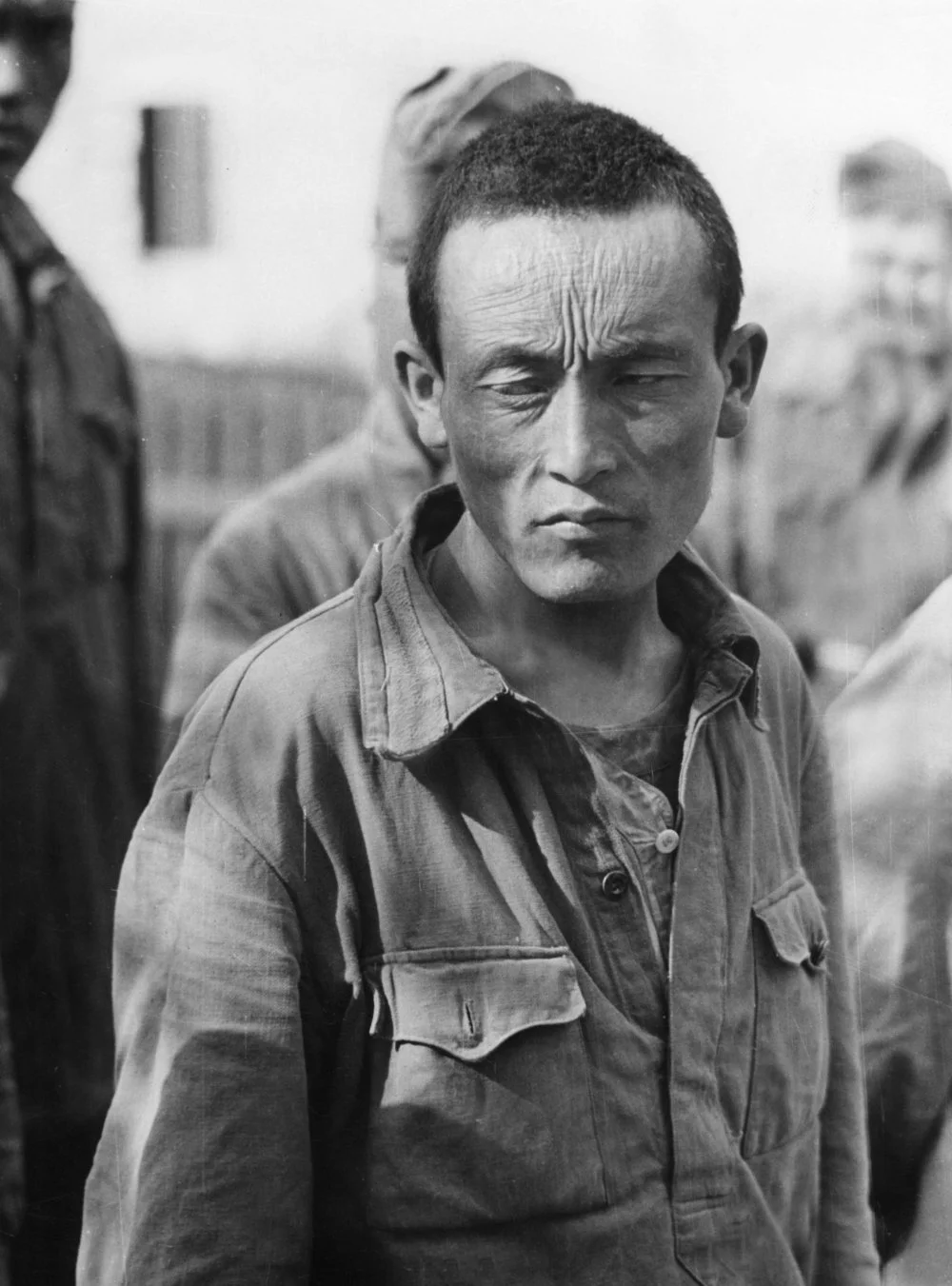

Captured soldier of the Red Army. Circa 1941 / Alamy

The Legal Status of POWs and the the Soviet Stance on the Geneva Convention

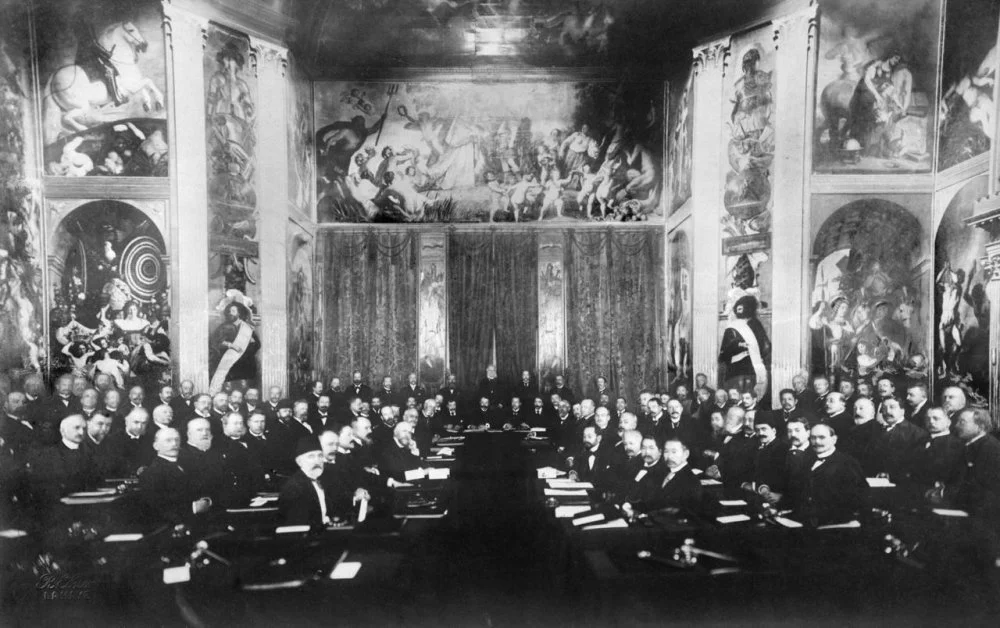

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the international community began developing the first treaties to regulate wartime conduct and define the legal status of POWs. The first such agreement was signed on 10 May 1864 between Austria, the Netherlands, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, and Sweden, and in the years that followed, nearly all the European states joined the agreement.

The countries involved in the First World War followed the Hague conventions of 1899 and 1907. The document, adopted on 18 October 1907, included a separate section specifically related to POWs, clearly defining their legal status and fundamental rights. During the First World War, for example, the interests of Russian POWs were represented by Spain, who acted as a protecting power. The interests of British, French, and Serbian POWs were safeguarded by the United States, who also provided assistance to Russian prisoners. As a result, all POWs were able to claim the rights granted under the Hague conventions.

The First International Peace Conference in Hague. May – June 1899 / Imperial War Museum / Wikimedia Commons

After the First World War, it was clear that holding hundreds of thousands of POWs was not simply a logistical challenge—it also exposed serious gaps in how international law protected them. Feeding, clothing, and eventually repatriating the POWs required huge resources and called for more detailed regulation of their conditions in captivity. Since the provisions of Article 17 of the Hague Convention of 1907 proved insufficient, the International Committee of the Red Cross organized a special conference in 1921 to discuss a new agreement. Its main breakthrough was that, for the first time, the rights of POWs were treated not merely as part of the general laws and customs of war, but as a distinct legal category.

After thorough deliberation, the Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War, 1929, was signed on 27 July 1929. This crucial international document clearly outlined the rights of POWs from the moment of capture to their repatriation. It established specific obligations for the detaining states, including conditions of confinement, the provision of medical care to wounded and sick prisoners, and many other key aspects, and all forty-seven countries who participated in the conference supported the agreement.

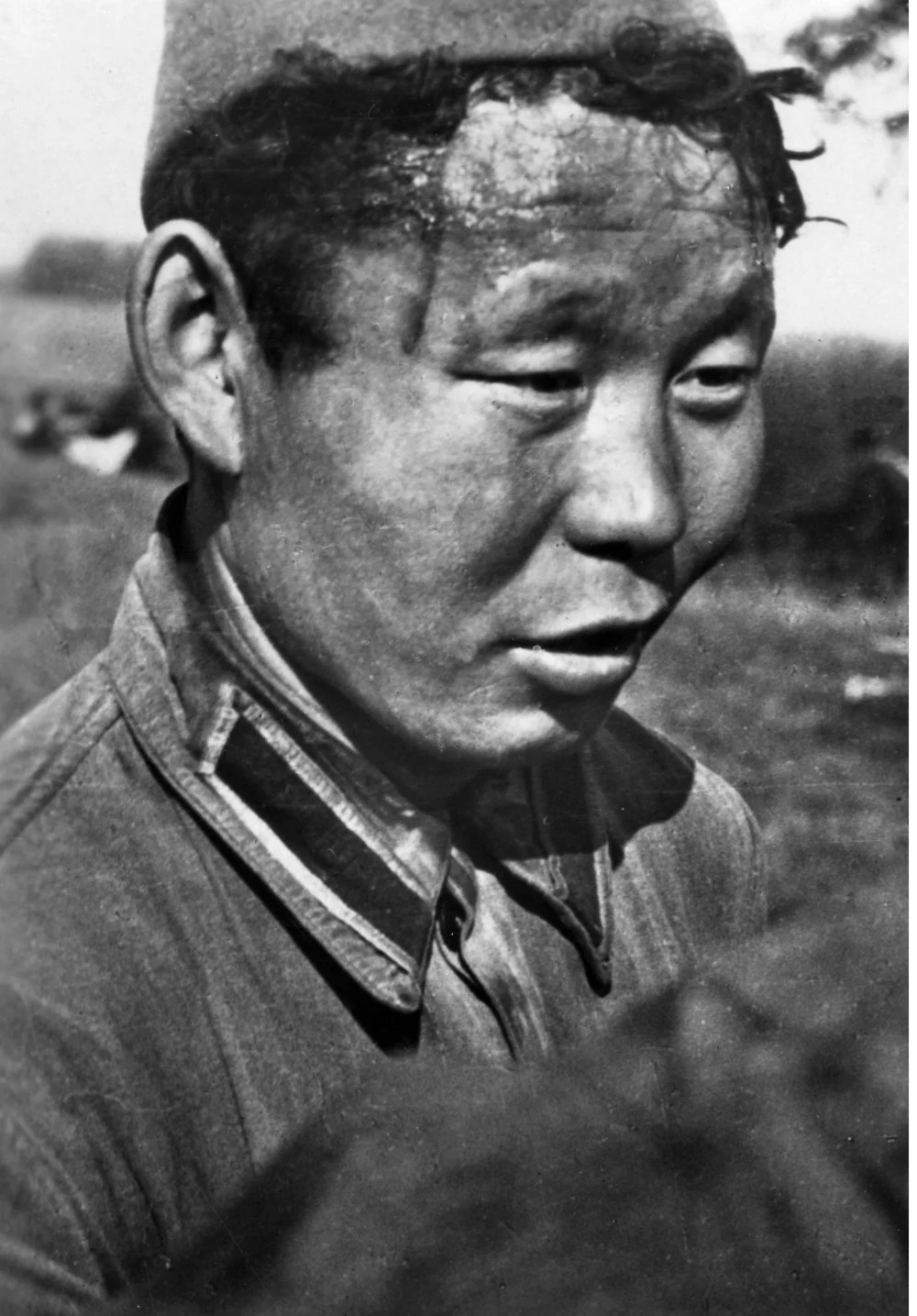

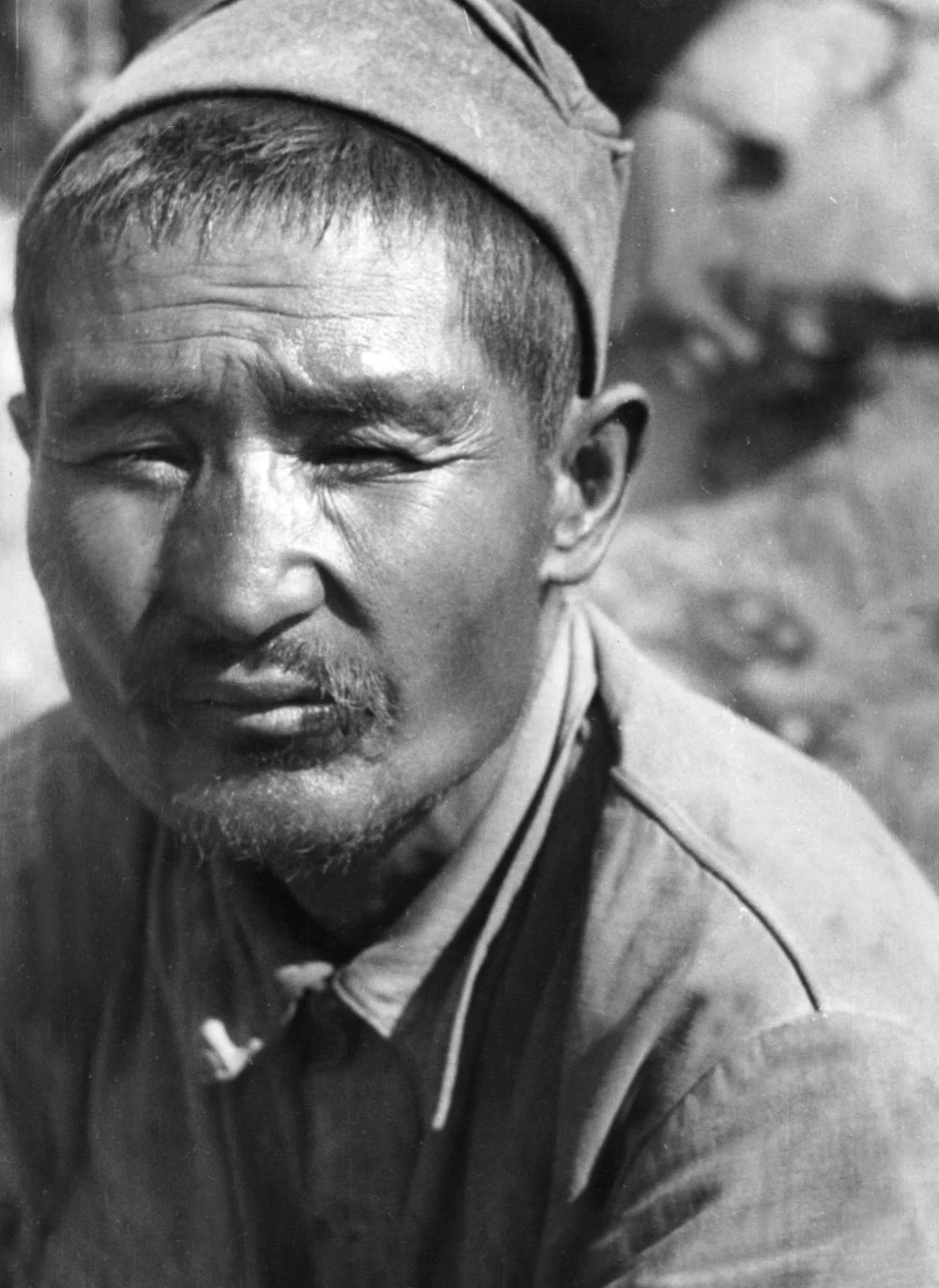

Officer of a Soviet military engineer unit captured by the German 19th Panzer Division near Dzisna on the Daugava River, Belarus. Circa July 1941 / INTERFOTO / Alamy

According to the Geneva Convention, POWs were subject to mandatory registration, and lists of captives were forwarded to a protecting power, designated as Switzerland. POW camps were regularly inspected by representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross. The prisoners’ food rations were not allowed to fall below the standard set for the rear-echelon troops of the detaining country. Under the new rules, prisoners were allowed to receive parcels from their home countries as well as humanitarian aid from the Red Cross, including food, vitamins, and medicine. They were also granted the right to submit complaints and statements regarding poor conditions in the camps.

Soviet Prisoners of War. Women of the Red Army / Alamy

Nazi Germany joined the Hague Convention on 21 February 1934i

A convoy of Soviet POWs near Kharkov. 1942 / Sovfoto / Universal Images Group / Getty Images

Nazi Germany’s treatment of Soviet POWs in the Second World War was predetermined from the outset. Hitler repeatedly emphasized that the war against the USSR was not merely an armed conflict, but a ‘clash of two worldviews’i

This is a struggle between two ideologies. The extermination of Bolshevism cannot be regarded as a social crime, since communism poses a tremendous threat to the future. We must not be guided by the principle of soldierly comradeship. A communist has never been and never will be our comrade. This is a merciless war of annihilation.

Soviet prisoners of war on the Eastern front. 1942 / Alamy

The Soviet Union’s refusal to join international conventions played into the hands of Nazi Germany. As part of Operation Barbarossa, a special directive was issued on 16 June 1941, outlining the fate of Soviet POWs in the coming war. The document emphasizedi

Bolshevism is Germany’s mortal enemy. Therefore, captured Red Army soldiers must be treated with particular caution.

… Any, even the slightest form of resistance, must be suppressed ruthlessly and decisively. Any active display of discontent must be eliminated immediately. Prisoners are strictly prohibited from communicating either with the local population or with the soldiers guarding them. Our adversary has not recognized the Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War of 27 July 1929.

At the same time, the directive itself included a number of provisions that flagrantly violated international law. For instance, prisoners were to be used not for economic work but exclusively for military purposes. They were not to receive any pay for their labor, and officers and medical personnel were denied even minimal financial support. Information about prisoners was not to be passed on to the military information services.

Soviet Prisoners of War in Freight Cars. Belarus, September 21, 1941 / German Federal Archives

In addition, other strict prohibitions were also imposed: prisoners' diets were regulated by special instructions; they were forbidden from establishing contact with protecting powers or humanitarian organizations; and representatives authorized to defend their interests were not allowed into the camps. Moreover, criminal proceedings were initiated against POWs without adhering to the requirements of the Geneva Convention. These measures directly violated articles 6, 7, 14, 15, 16, and 17 of the Hague Convention, as well as articles 23, 31, 34–41, 43, 44, 77, and 79 of the Geneva Convention.

As early as 8 September 1941, Nazi troops were officially instructed to treat Soviet POWs with the utmost harshness, forbidding any expression of sympathy. However, it should also be noted that in addition to Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union itself violated international law regarding POWs.

Soviet prisoners marching to a concentration camp. Ukraine, May 1942 / Heinrich Hoffmann / Mondadori / Getty Images

Policies and practices of extermination

In the first months of the Second World War, communication between the front lines and army or divisional headquarters of the Eastern Front was disrupted, leading to the mass encirclement of thousands of Soviet soldiers and officers. Under these conditions, large-scale captures began. The disconnect between the high command and local units, along with poor coordination on the ground, led to chaotic retreats. This, in turn, made it difficult to gather information on the number of dead, wounded, captured, or missing soldiers and relay it to headquarters. It is worth noting that both German and Soviet sources from that time are unreliable: both sides heavily relied on ideological propaganda and distorted facts. And so, even in German academic literature, the figures for the number of Soviet POWs vary.

According to research conducted by Joachim Hoffmann, a total of 5.24 million people were captured during the Second World War, with 3.8 million taken prisoner in the first monthsi

Drawing of a captured Soviet soldier made by the German war correspondent Stucke. 10.8.1941 / INTERFOTO / Alamy

Christian Streit provides more detailed figures, and according to his data, in December 1941, there were 3,350,000 Soviet soldiers in captivity; by July 1942, that number was 4,716,903; in January 1943, 5,003,697; in February 1944, 5,637,482; and in February 1945, it was 5,734,528. Of these, 3.3 million—that is, 57.8 per cent of all Soviet POWs—perished in Third Reich camps from starvation, abuse, and repressioni

At the same time, Russian sources differ significantly from foreign ones. The Commission for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Political Repression under the President of the Russian Federation, led by A.N. Yakovlev, concluded: There is no exact and reliable data on the number of Soviet POWs between 1941 and 1945. According to official records from the German command, 5.27 million people were captured, whereas the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation puts the figure at 4.06i

Thus, the actual number of Soviet POWs and the number who died in captivity have not been definitively established. As for Kazakh POWs, the available data also varies and often contradicts itself.

Female doctors among a group of Soviet prisoners of war captured by Germans in Velikiye Luki. August of 1941 / Scherl / Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy

In the early years of the war, Soviet POWs died in large numbers. There were very few who survived the winter of 194–42 were few. On 14 December 1941, during a meeting with Hitler, A. Rosenberg reported that, according to General Kitzinger, around 2,500 people died daily from hungeri

Soviet prisoners of war at Stalag 326 camp, which housed 10,000 prisoners during World War II. Circa 1941 / CORBIS / Corbis / Getty Images

In the early months of the war, due to a lack of prison facilities, German troops housed Soviet prisoners in schools, destroyed factories and quarries, and fenced-off wastelands. By July and until September 1941, mass deaths of prisoners began in these temporary camps. On 10 July 1941, H. Dorsch, a representative of the Eastern Ministryi

In the camp, which is about the size of Wilhelmplatz, there are 100,000 prisoners of war and 40,000 civilians. The area is so cramped that people stand shoulder to shoulder, unable to move. Even their natural needs must be taken care of right there, on the spot. The camp is guarded by only one company. Due to the insufficient number of guards, the harshest control methods are applied. The prisoners receive almost no food and go without it for 6–8 days at a time. They become swollen from hunger, and think only about finding any kind of food.

Soviet prisoner. Circa 1941 / Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy

The conditions in the camps, however, were inhumane. Soviet POWs, who worked long hours from morning until late evening, were provided with food totaling only about 1,300 calories per day, while the standard requirement was 3,000 caloriesi

Female Soviet prisoners of war on the Eastern Front. 1942 / Scherl / Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy

The Tragedy of the ‘Turkestanis’

The grim fate of Soviet POWs has been examined in-depth by many scholars over the years, and yet, within this vast body of research, one group remains largely overlooked: the Asian POWs, especially those from Turkestan and other parts of Central Asia. As early as May 1941, a document titled ‘Instructions for Determining the Position of Groups of Troops in Russia’, prepared by the Supreme Command (Wehrmacht), contained the following directive in line with Nazi racial theoryi

Soldiers and prisoners of the Red Army should be treated with special suspicion and extreme caution. In particular, Asian soldiers appear to be extremely incomprehensible, cruel, and treacherous.

Hitler, in turn, viewed Asian civilizations as a serious threat to Europe and stated: ‘Now it becomes clear why the Chinese built the Great Wall to protect themselves from Mongol invasions. We also need a grand wall to protect ourselves from the masses of Central Asia …i

Soviet POWs during Second World War. Circa 1941 / Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy

On 24 July 1941, a chilling order was issued by the German High Command: Asian soldiers captured while serving in the Soviet army were not to be transported to Germany. Instead, they were to be held in camps scattered across the occupied territories. The order was explained by claiming that prisoners with Asian features were allegedly unsuitable for agricultural labor of the Third Reich. After an order like this, the officials responsible for the policy toward POWs began to treat prisoners of Asian origin with particular suspicioni

Soviet Union, Soviet prisoners of war. Ukraine, circa summer of 1941 / Alamy

Information about the national composition of Soviet POWs remains frustratingly limited. One of the few official sources is a postwar statistical report compiled under the supervision of Colonel General G.F. Krivosheev. According to this document, a total of 1,836,562 Soviet citizens returned from German captivity by the end of the war and in the years that followed. Of these, about a million were re-drafted into the Red Army, 600,000 were sent to labor battalions to work in industry, and 339,000 people, accused of offenses related to their time in captivity, were sent to camps of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs. Among the returnees were 23,143 Kazakhsi

Column of Soviet prisoners of war. Circa 1941 / Alamy

In German documents, Soviet POWs from Kazakhstan and the Central Asian republics were grouped under the general name ‘Turkestanis’. However, data on the number of Turkestanis in captivity is extremely limited and often contradictory, primarily due to the catastrophic mortality rate among prisoners during the winter of 1941–42. As reported by Major V. Uslar, a representative of the General Staff of the Army, at a meeting with General E. Koestring and Dr R. Niedermaier in Mirgorod on 1 August 1942, about 80 per cent of the 100,000 Turkestani POWs died in the first winter of the wari

Soviet prisoner of war. Circa 1941/ Alamy

In recent years, the State Commission for the Full Rehabilitation of Victims of Political Repressions has conducted significant work. Thanks to the study of special archival funds and by analyzing published materials, it has been possible to gather essential data about Kazakhstan's POWs and trace what happened to them. To date, it has been established that from 1939 to 1945, 65,755 soldiers and officers from Kazakhstan were taken prisoner. The death of 4,082 Kazakhstani individuals in captivity has been confirmed.

Captured soldiers of the Red Army. Circa 1941 / Alamy

The tragic history of Soviet POWs is not just merely one episode in the Second World War; it is also a bitter testimony to how a ruthless political system could erase human faces from the memory of the people, depriving millions of people not only of their freedom but also of their right to compassion. Today, after decades, we are beginning to learn the truth, and with it comes hope for the restoration of justice, including for the Kazakhs, whose names had long been forgotten.

Soviet Prisoners of War / Hulton-Deutsch Collection / CORBIS / Corbis via Getty Images