Fresco inside the palace Chehel Sotoun built by Shah Abbas II to be used for his entertainment and receptions. Isfahan, 17th century/Wikimedia commons

The festival of Nauryz (Nowruz) symbolizes the beginning of spring and the start of the new year. From Kazakhstan to Iran (and other parts of the world!), Nauryz draws people together to celebrate their heritage through a rich collection of customs and ceremonies. Explore the significance of Nauryz by finding out the stories of its origins, the date it is celebrated on, and the importance of the number seven to its festive table.

Characterized by joyousness, hope and rejuvenation, Nauryz (more commonly spelled as Nowruz in Iran) is one of the most widely celebrated and beloved festivals in the world. In Kazakhstan, it is celebrated on 21–22 March, symbolizing the transformation of the Earth during spring and welcoming the new year. Nauryz is celebrated in various countries and regions, including Iran, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Tatarstan, and Bashkortostan, as well as in Dagestan and other regions of Russia. It is also celebrated in Xinjiang, Iraqi Kurdistan, India, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and even in Europe in the Balkans, such as in Macedonia, Albania, Bosnia, and Herzegovina.

Recognized by UNESCO as an international holiday since 2009, it was celebrated at their headquarters in Paris for the first time on 24 March 2015. The event was grandly organized by the International Organization of Turkic Culture (TÜRKSOY), which unites fourteen countries through its headquarters in Ankara. It is worth noting that in that year, the director-general of this organization was Duisen Kaseinov, the former Kazakh minister of culture.

The History of the Celebration

The name of the holiday originated in ancient Iran and consists of two ancient Iranian words, nou, meaning ‘new’, and ruz, meaning ‘day’, leading many to believe that it is originally a purely Iranian holiday. As a Zoroastrian tradition, Nauryz does not originate from the territory of historical Iran, which was slightly larger than the territory of the present-day Islamic Republic of Iran, and certainly not from Persia, but slightly to the north instead. Those lands were recorded as Turan in ancient Iranian literature, and they were the lands of alien, Iranian-speaking nomadic tribes. Later, the name Turan lost its mythical connection with the nomadic Iranian-speaking tribes and became a geographical synonym for Central Asia. Eventually, it became the synonym for the entire Turkic world, encompassing both its nomadic and settled peoples.

Bas-relief the lion-bull combat in Persepolis—a symbol which has been variously interpreted, including as the symbol of the Nowruz(the Persian New Year's Day)—in day of a spring equinox power of eternally fighting bull (personifying the Earth), and a lion (personifying the Sun), are equal/Anatoly Terentiev/Wikimedia Commons

After migrating to the territory of Iran, nomadic Indo-Iranian confederations gradually transitioned to a settled way of life. After that, the cultural divide between the settled Iran and predominantly nomadic Turan became more pronounced as was often reflected in ancient Iranian literature. It is indicative that even the name of the prophet Zarathustra, who was a man from the eastern Iranian lands, means ‘camel driver’, leaving no doubt about the nomadic lifestyle of his compatriots. Therefore, Nauryz is often associated with the ancient traditions of Turan and the nomadic prophet who preached the teachings of One Creator, bestowing love, blessing, support, and light.

Interestingly, ‘Zarathustra’ or ‘Zardusht’ sounds very much like the Kazakh word ‘Jaratushy’ (meaning ‘creator’), which in itself generates folklore associations about the wise man who brought the Iranians a new belief of the One Creator. His teachings, the Gathas, were recorded and disseminated by followers, from whom emerged the caste of Mobad priests. They created the Avesta, written in the Avestan language,1

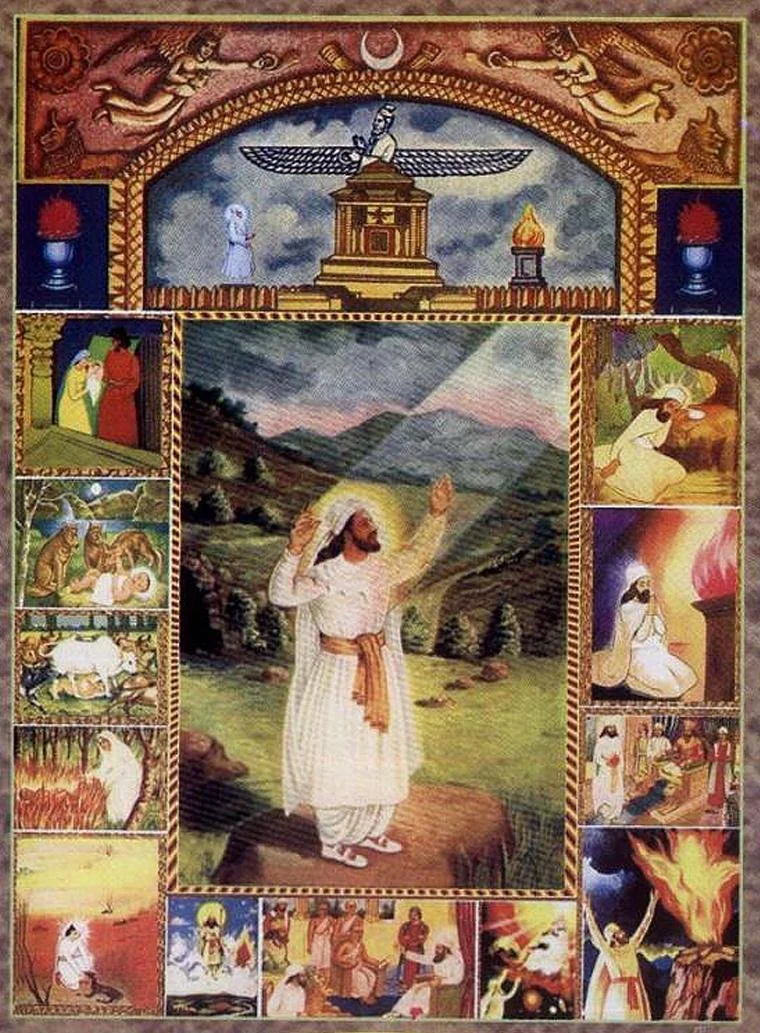

Life of Zoroaster, founder of Zoroastrianism/Wikimedia Commons

Determining the life span of the prophet Zarathustra, also known as Zoroaster, is quite difficult. However, most researchers believe that he lived between between the eleventh and sixth centuries BCE.

History tells us that Alexander the Great1

The Eastern scholar Vyacheslav Shukhovtsov, a student of Professor V.S. Sokolov, was the most outstanding expert in the world on the Avestan language and Zoroastrianism during his lifetime. He adhered to the opinion that the Airyanem Vaejah mentioned in the Gathas, the homeland of the Aryans, from where Zarathustra came, was located in the Jetisu region. This coincides with the opinion of the Russian historian and writer Evgraf Saveliev: ‘According to the Rig Veda and the Avesta, the homeland of the Aryans is the land of “perfect creation” ... bounded ... by high mountains, from where seven rivers originated …—our Semirechye, in present-day Turkestan.’

Perhaps we will find out in the foreseeable future if this was really the case.

Some scholars also have different theories of where Zarathustra originated from, suggesting areas including the South Urals and Central and East Kazakhstan. Other researchers speculate about the homeland of the Aryans, placing it in locations such as the Fergana Valley, Azerbaijan, the Valdai Uplands, and even in the vicinity of the North Pole.

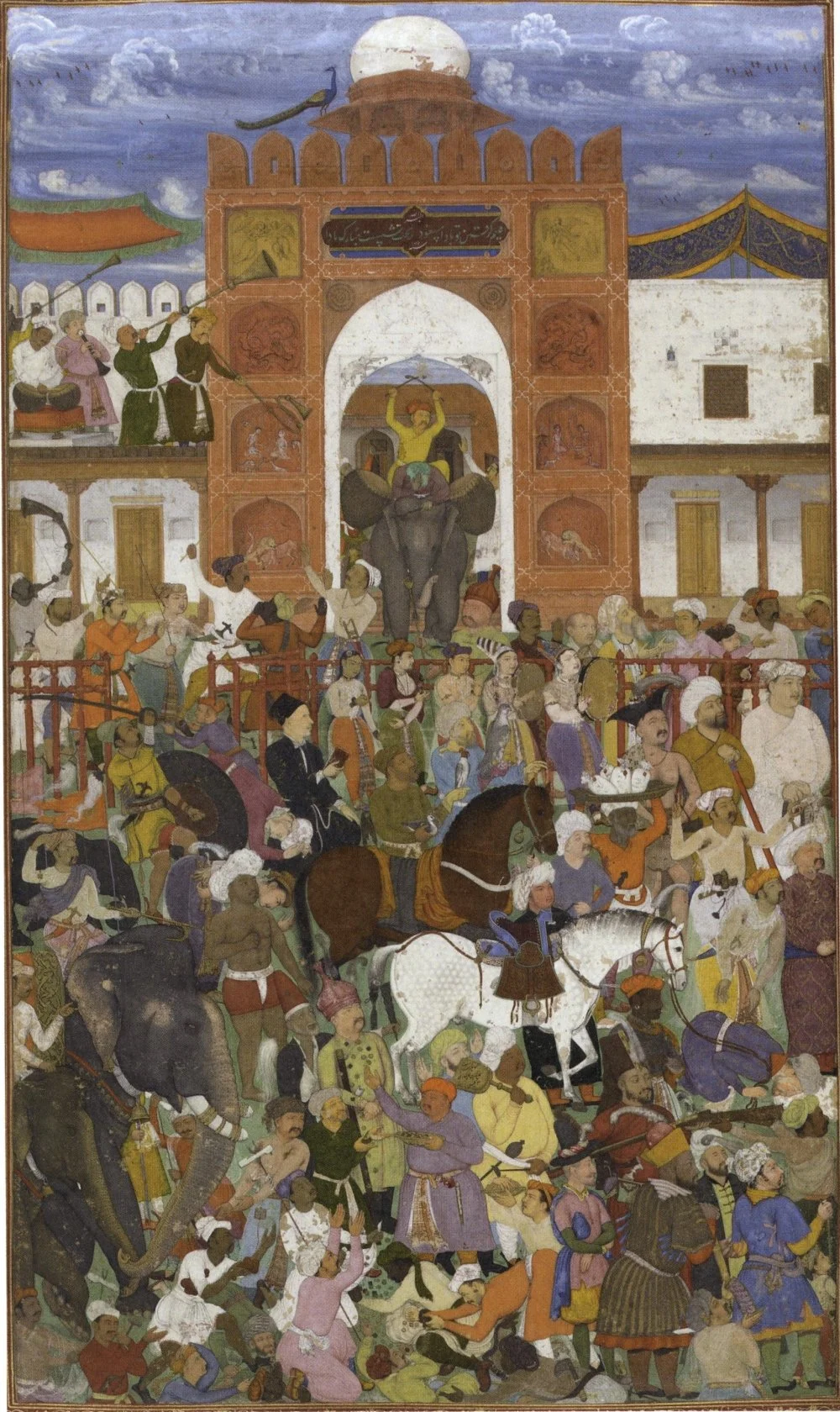

Nauroz durbar of Jahangir (left half), From the St. Petersburg Album. India, 17th century. Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Oriental Manuscripts/Wikimedia Commons

However, it is most likely that the prophet preaching ‘Jaratushy’ (creator) represented the proto-Scythian-Saka lineage, which came from the ethno-cultural complex of Indo-European and Ural-Altaic peoples. This version is reflected in the legendary genealogies, beliefs, and rituals of ancient Slavs, Finno-Ugric peoples, Turks, Mongols, Iranians, and Tungusic-Manchurians. Thus, several Turkic peoples have continued the tradition of celebrating Nauryz since prehistoric times.

Among the Kazakhs, this holiday is also called Ūlystyñ ūly küni, which translates to ‘Great Day of the People’ in Russian. This echoes the mythological history of the Turkic-Mongol peoples, narrating their ancestors' exodus from Ergenekon, where they escaped enemies and became a nation of skilled blacksmiths and warriors. According to the legend, they then melted an obstructing mountain pass and entered a new era of prosperity.

Cultural researcher Serik Ergali from Astana, citing ancient petroglyphs located 170 kilometers northwest of Almaty, near Mount Añyraqai, reports that the tradition of celebrating Nauryz on the day of the spring equinox in the territory of Kazakhstan dates back thousands of years. These ancient drawings are approximately 5,000–6,000 years old and depict the connection between Nauryz and the twelve-part Turkic calendar.

Omar Khayyam, a Persian who lived in the state of the Great Seljuks,2

Amal Körisu

An interesting fact about the holiday is that residents of the West Kazakhstan, Syr Darya, Kostanay regions, and Torgai, as well as of the Russian regions of Astrakhan, Saratov, Samara, and Orenburg, celebrate the beginning of the year and spring on 14 March as the holiday of Amal Körisu. Translated from Kazakh, körisu means ‘meeting’ or ‘encounter’.

On this day in these regions, it is customary to wake up early in the morning to greet people, starting with the elders, and congratulate them on the arrival of spring. This is accompanied by warm wishes such as ‘Jasyñ qūtty bolsyn!’ (May you be blessed with another year of your life!) and ‘Jasyña jas qosylyp, ğūmyryñ ūzaq bolğai!’ (May you add many years and have a long life!).

During the Amal Körisu holiday, it is very important to show respect for your elders, care for your younger family members, support the weak, help the poor, forget grievances, and reconcile with those you have quarreled with. The elders bless the young, and many people hug each other, while young people simply shake hands with the elders. It is not customary for daughters-in-law to hug their fathers-in-law and brothers-in-law, but it is acceptable to hug their mothers-in-law and sisters-in-law.

Traditional kazakh family waits for guests in a traditional yurt during the Nowruz holiday/Alamy

In ancient times, this day symbolized the end of harsh winter days for nomadic Kazakh herdsmen. On this day, they would visit each other, congratulate one another on the arrival of the spring and New Year, and exchange news.

In 2019, Kazakh senator Sarsenbay Ensegenov proposed making the Amal Körisu holiday an official one. ‘Körisu küni is not a holiday of a particular region or just the Kazakh people. Its boundaries have expanded, and its role in public life grows. And now our citizens abroad celebrate this day,’ he noted. President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev officially congratulated the Kazakhs on Amal Körisu on 14 March 2023. Who knows, perhaps in the future, this day will become a national holiday in the country's calendar.

The fact that western Kazakhstan celebrates Nauryz earlier than other regions is explained by several aspects. One of them recounts how representatives of the Younger Horde and Western Kazakhstan brought this tradition from the east, where they once lived and where Tuvans and Mongols still adhere to it. Another story says that all the Kazakh people initially celebrated the beginning of the new year in the middle of March, and the shift in date occurred with their transition to the Gregorian calendar.

Symbolism of the Number Seven and the Festive Table (Dastarqan)

The main Kazakh treat on the festive table is Nauryz köje. This ritual dish is a soup made from seven ingredients: water, meat, salt, fat, flour, grains, and milk. The number seven holds a sacred meaning for many peoples, and Kazakhs are no exception. The seven components of the Nauryz köje represent the seven elements of a happy life: joy, wisdom, luck, health, wealth, agility, and heavenly protection from evil. The enormous cauldron in which this dish is cooked symbolizes unity, abundance, and prosperity. The seven ‘magical’ items and products on the table become symbolic gifts to the sun. It is believed that by accepting such gifts, the sun ensures a bountiful harvest.

Meanwhile, Tajiks avoid putting dishes made from meat and other animal products on the festive table except for milk-based ones.

In Central Asia, a special table is set for Nowruz called haft-sin. It must contain seven (haft) items whose names start with the Arabic letter ‘sin’: rue seeds (sipand), apple (seb), black seeds (siyah dane), wild olive (sandjid), vinegar (sirke), garlic (sir), and sprouted grains (sabzi).

Another set of seven items is possible in other countries. For example, in Iran, these include coins (sekke), vinegar (serke), garlic (sir), sumac (sumah), sprouted wheat grains (sumanak), oleaster berries (sandjed), and greens (sabze), as well as sprouted flax and cereal seeds, symbolizing the rejuvenation of nature.

Another symbol of Nowruz and the New Year is a distinct treat called sumanak (sumalak), which is a thick, dark soup made from boiled and mashed sprouted wheat grains.

Rituals, Games, Omens, and Fire

According to Serik Ergali, a cultural researcher, Kazakh traditions, national games, and rituals associated with Nauryz, such as Alastau, Aitys, Kökpar, and Altybaqan originate from ancient Turkic celebrations that mark the awakening of the Earth after the winter. The ritual of Bastañğy, the Kazakh custom of greeting the sunrise and the sun on the day of the Nauryz holiday, is mythologically linked to the image of the holy elder Qydyr, or Qydyr-Ata, who comes to visit people invisibly on those days and blesses them. Many peoples have a tradition of lighting bonfires at this time and jumping over these to cleanse themselves for a new life. However, the Kazakhs have long considered this a bad omen and disrespectful to the fire itself. Instead, they limit themselves to the ritual of lighting a candle, bringing their palm close to its flame and lightly touching it to their faces. It was also customary to walk around every corner of the house with the lit candle, thus performing a cleansing ritual.