The term ‘asharshylyq’ refers to the mass famine that struck Kazakhstan in the 1930s, a tragedy that is etched deep into the country’s history. The Kazakh steppe, however, was no stranger to famine—it had occurred repeatedly throughout the nineteenth century, with nearly every decade bringing its own wave of suffering. To this day, we do not know the exact number of victims of these events. The Soviet era, however, brought even more tragic years as famine took on a new scale and nature. People perished not only due to drought or jut (a harsh winter leading to mass livestock deaths due to a lack of pasture) but also because of brutal and misguided policies. Historian Sabit Shildebai examines how famine transformed Kazakh society and identifies the underlying causes that contributed to this tragic cycle.

The Famine in Kazakhstan: Key Periods and Root Causes

The Kazakh people endured several devastating famines during the Soviet era. Between 1917 and 1919, famine affected Kazakhs in the Jetisu and Syr Darya regions of the Turkestan Republic. Between 1921 and 1923, it struck the Orenburg, Aktobe, Kostanay, Ural, and Bukei provinces, as well as the Adaev district, territories that were part of the Kazakh ASSR. From 1927 to 1934, a large-scale famine swept across the Soviet Union, including all of Kazakhstan. According to various estimates, more than 2 million people perished, which at that point was nearly half the Kazakh population.

It is incredibly difficult to grasp the full scale of that tragedy. But did famine occur in the steppe before the Soviet regime? Historical records confirm that drought and jut had repeatedly led to humanitarian disasters in Kazakh lands. For example, Seitkali Mendeshev, the chairman of the Emergency Commission for Famine Relief under the Central Executive Committee of the Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic (ASSR), emphasized this in his report titled ‘Famine in the Kazakh Steppe and the Fight Against It’, which was presented at the Second Regional Conference of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (RCP(b)) in Orenburg between 19 and 27 February 1922:

In the republic, periods of famine recur regularly. Historical records document years of famine in the provinces that were part of the republic: 1802, 1810, 1833, 1840, 1859, 1864, 1876, 1880, 1891, 1896, 1911, and 1921. As seen from historical sources, famines occurred in the Kazakh steppe nearly every ten years. Almost every time, a drought was observed a year before the famine began, and then, over the next two years, the situation worsened due to poor harvestsi

Historian Svetlana Smagulova, the author of two monographs on famine, analyzed the frequency of mass disasters in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as follows:

One of the causes was the mass death of livestock triggered by natural disasters (droughts that scorched pastures, crop failures due to harsh winters, and so on), which contributed to the spread of famine among the population. Another cause was the miscalculated and ill-conceived policies of the authorities governing the region during the times of both disastersi

Another cause of famine—alongside miscalculations by the Soviet authorities, droughts, and dzut—was the nomadic way of life and the lack of food preservation practices, which affected the population’s ability to ensure its own food security.

The Famine in Turkestan in 1917–19

The first wave of famine at the end of 1917 struck the peoples of the Turkestan Republic, particularly the local populations of the Jetisu and Syr Darya regions. Prior to this, they had already endured waves of punitive military operations following the national liberation uprising of 1916. In 1918, the mortality rates among the adult population in those areas rose to 30 per cent, and in some districts reached as high as 75 per centi

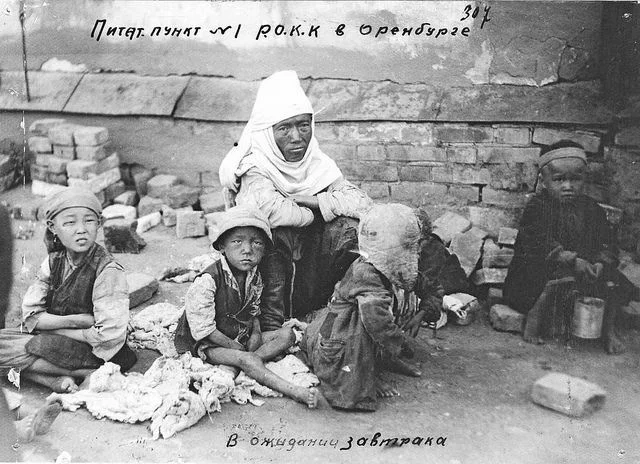

Photograph presumably taken by the Russian Red Cross Society / From the private collection of Sabit Shildebay

Several factors contributed to the famine in Turkestan. Nearly all the arable land in the region had been allocated to cotton cultivation, and the planting of grain crops was prohibited. A sharp rise in taxes during the First World War, along with punitive expeditions and looting following the 1916 uprising, had already left the population destitute. The situation was worsened by the February and October revolutions of 1917, the devastating effects of the civil war, a two-year drought from 1917 to 1918, and the poorly thought-out policies of leaders appointed by the central government to manage the Turkestan ASSR. All of this together led to a widespread and severe famine.

Ivan Tobolin, who initially headed the Tashkent City Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and later the Central Executive Committee of the Turkestan ASSR, openly stated:

The Kirgizi

This stance effectively amounted to a deliberate refusal to act in the face of mass starvation among the local population. In 1919, a representative of Turkestan, U. Shakirov, wrote in a letter to Stanislav Pestkovsky, Deputy People’s Commissar for Nationalities of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR):

The current policy of the Turkestan government toward the native population is a crime that has led to total impoverishment and the death of 60 per cent of the people.

Turar Ryskulov’s Entry into Politics

In the spring of 1918, Turar Ryskulov interrupted his studies in Tashkent and returned to the Aulie-Ata district. Along with other members of the ‘Bukhara’ organization, he joined the Bolshevik Party, aiming to use their access to political and military resources to aid the starving population. Under Ryskulov’s leadership, Kazakh activists quickly formed an influential political group. On 21 April 1918, he was appointed to the Aulie-Ata district council, and that summer, he was elected chairman.

Turar Ryskulov / Wikimedia Commons

In 1918, a severe famine engulfed not only the Aulie-Ata district but the entire Turkestan region. By autumn, the number of starving people had reached nearly 2 million. Weakened and emaciated, people were dying en masse from infections and epidemics. Turar Ryskulov understood that to stop the catastrophe and save his people from death, he needed significant influence, and to gain that, he had to join the regional government. In the fall of 1918, during the Sixth Congress of Soviets of Turkestan, he was elected to the Central Executive Committee of the Turkestan ASSR and appointed the People's Commissar for Health.

In November 1918, Ryskulov founded the Central Commission to Combat Famine. At that time, he was only twenty-four years old, but despite his youth, he quickly gained authority within the government and became one of the most prominent figures in Turkestan. Thanks to his organizational skills, the Bolsheviks were forced to acknowledge the scale of the tragedy and allocate resources for food and relief efforts. Branches of the Commission to Combat Famine were established across the republic at the republican, provincial, district, volost, and city levels. As a result, approximately 1,200 public dining halls, orphanages, and clinics for infectious diseases were established.

It is crucial to note that, on Ryskulov’s initiative, about 11,000 volunteers from among the youth of Turkestan joined the commission. In essence, he became the founder of the volunteer movement in the republic. After several months of intense work, by the spring of 1919, the scale of the famine in the region had been significantly reduced, and around 1 million lives were saved.

A medical team examines residents of one of the villages of the Akmola region. The Kazakh ASSR. 1928 / RIA

However, to this day, we still do not know exactly how many people died in the Turkestan Republic during those years. The data varies greatly: for example, Mustafa Shokay wrote in his notes that 1,114,000 people died from famine.

According to the Qazaq newspaper, in July 1917, the Syr Darya region was home to 1,272,290 Kazakhs, and the Jetisu region to 857,982, totaling 2,130,272 people. However, by the time the 1926 census was conducted, these regions, now part of the Kazakh ASSR, recorded only 1,428,989 Kazakhs.

Even accounting for natural population growth, the Kazakh population in the region decreased by 701,283 people over a nine-year period.

The Famine of 1921–1923

The famine of 1921–22 affected not only five provinces and one district of Kazakhstan but also more than thirty provinces in Soviet Russia. The situation was especially dire in the Samara and Saratov regions, the Volga region, southern Ukraine, Crimea, Bashkortostan, the Urals, and western Siberia. Of 90 million people living in the thirty-five affected provinces, nearly 40 million suffered from famine, though official data reported that 22,558,550 people were affected. Over 5 million people died. And these figures remain imprecise. To this day, no comprehensive academic study has determined the total number of deaths caused directly by the 1921–22 famine or by the epidemics and infectious diseases that resulted from it.

Illustration album «La Famine en Russie». Geneva, 1922 / From the private collection of Sabit Shildebay

The scale of the famine in Kazakhstan in the early 1920s can be assessed through population census data from 1920 and 1926. According to the demographic census completed on 28 August 1920 (excluding territories that were part of the Turkestan ASSR), Kazakhstan had a population of 4,781,263 people. Of these, 402,751 lived in cities and urban-type settlements, 18,695 in areas classified as part of the railway zone, and 4,359,817 in rural areasi

According to another census, the agricultural census completed by the end of October 1920, the number of rural residents in the Kazakh ASSR was slightly higher, at 4,369,650 people, which was almost 10,000 people more than the previous count. In addition, both censuses failed to account for 157,120 nomads who were temporarily absent at the time of data collection. According to the Statistical Administration of the Kazakh ASSR, the total number of registered residents in the autumn of 1920 was 4,938,383 peoplei

If we add up all discrepancies and include the population omitted for various reasons, as well as the personnel of military units stationed in the republic (for which precise figures are unavailable), we can conclude that in the autumn of 1920, the population of the Kazakh ASSR was approximately 5 million people.

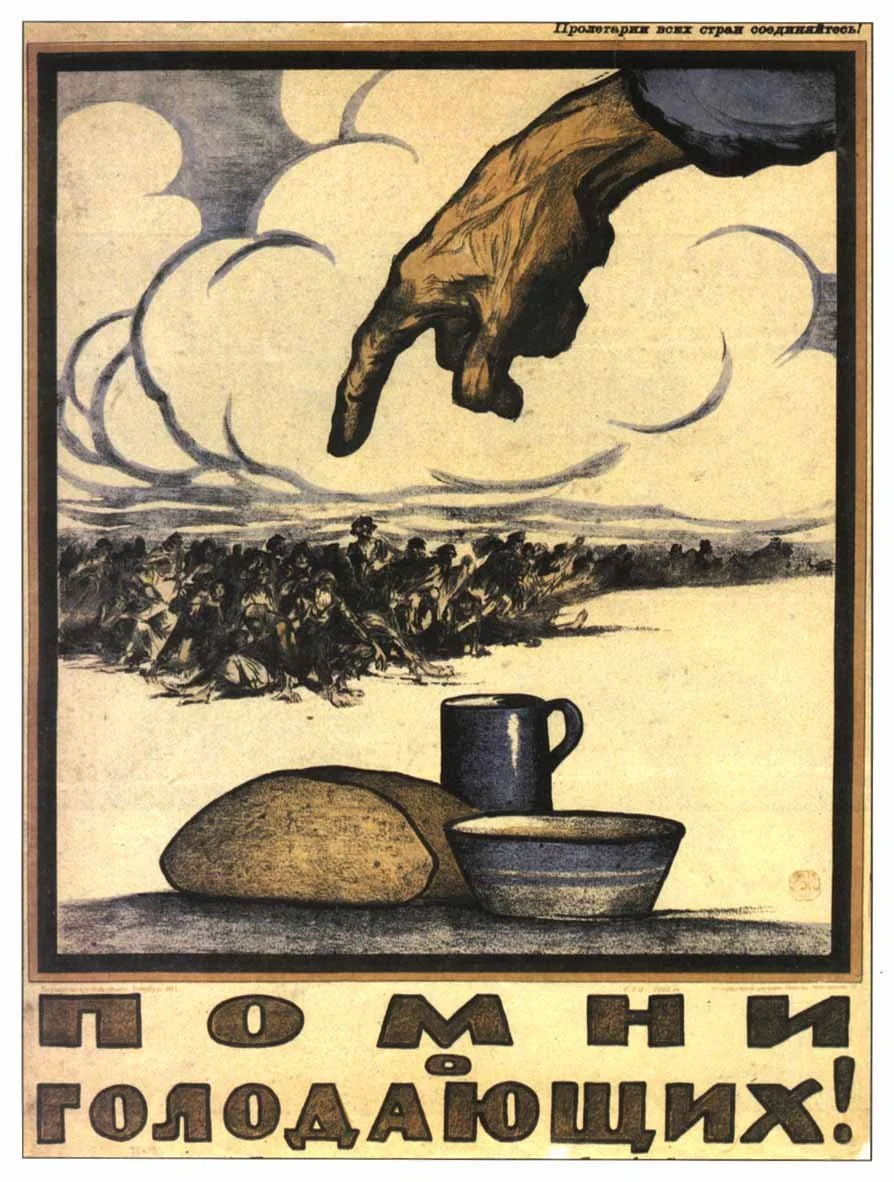

Soviet poster «Remember the starving». 1921 / Wikimedia Commons

However, by 1923, the population of the Kazakh ASSR had dropped to 3,786,910 peoplei

Based on the previously provided figures, this means that between 1920 and 1923, the population of the republic decreased by 1,151,473 people.

Such a significant decline requires a detailed analysis: how many people died directly from starvation, how many from infectious diseases and epidemics, and how many were forced to leave their native lands, migrating to neighboring regions.

The Causes of the 1921–1922 Famine

The famine that swept across the Kazakh steppe had many causes, some of which we have already discussed. In the spring of 1921, a prolonged drought began, destroying grain and fodder crops. However, even before that, agriculture had been severely damaged by a series of disasters: the civil war of 1918–20, the failed harvest of 1920, and widespread livestock deaths in 1920–21. All of these factors combined to exacerbate the impending famine.

Emaciated horse. USSR, 1932 or 1933 / Alamy

An additional blow came from the policy of ‘war communism’ implemented by the Soviet authorities: it led to a decline in peasants’ motivation to work, a reduction in cultivated land, and a sharp drop in livestock numbers. In 1917, the land under cultivation in Kazakhstan totaled 5,840,000 desyatinasi

A similar situation played out in terms of animal husbandry: in 1917, there were 29.7 million heads of livestock in the Kazakh ASSR; by 1920, 9.7 million; and by 1921, only 6.2 millioni

Illustration album «La Famine en Russie». Geneva, 1922 / From the private collection of Sabit Shildebay

These figures clearly illustrate the catastrophic state of agriculture in the region. In 1921, even under the optimistic estimate of 32 poodsi

But even the projected 70 million poods were never harvested. A significant portion of the crops was damaged by drought and completely destroyed by a locust invasion, leading to crop failure over vast areas. As a result, food shortages were already being felt by the summer of 1921 and soon turned into widespread famine for the population.

How the Famine Was Fought in 1921–1922

Immediately after the famine began, the Bolshevik Party, led by Vladimir Lenin, raised the alarm and took urgent measures to combat the disaster. On 18 June 1921, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK)i

Similar commissions were established in all the autonomous national republics and regions, provinces, and districts of the RSFSR. Among them was the Emergency Commission for Famine Relief (ECFR) under the Central Executive Committee of the Kazakh ASSR created on 8 July 1921.

Mikhail Mikhailovich Cheremnykh. Awaken, citizens! Hunger is no longer suffering — it is terror! 1922 / Heritage Art / Heritage Images via Getty Images

The Emergency Commission was chaired by Seitkali Mendeshev, the chairman of the Kazakh Central Executive Committee. Its initial membership included the People's commissars of Food Ilya Shleyfer; of Land and Water Affairs Vasily Kharlov; of Social Security Alibi Zhangeldin, as well as a representative of the People's Commissariat of Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectioni

The famine that struck the Kazakh land was described by Seitkali Mendeshev as follows

In May 1921, it was expected that the sowing areas would be favorable and the harvest would be no less than average. However, the drought that began in July and lasted for an extended period, followed by a locust invasion, like a cloud covering the fields, completely destroyed the crops. The first signs of famine in the Kyrgyz Republic were accompanied by a mass exodus of peasants, with destitute and starving refugees concentrating in the cities. Among them, diseases and death spread rapidly. Crowds of homeless children, naked and unattended, wandered the streetsi

On 6 October 1921, at the fourth session of the Second Congress of Soviets of the Kazakh ASSR, the acting People's Commissar for Food, Shleyfer, presented a report titled ‘On the Fight Against the Famine’. Following the discussion, a resolution titled ‘On Measures to Combat the Famine’ was adoptedi

According to its final provisions, on 25 October 1921, the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the Kazakh ASSR expanded the composition of the ECFR, transforming it into the Central Commission for Famine Relief (TsKPG)i

By November 1921, the number of starving people throughout the republic reached 1,558,927i

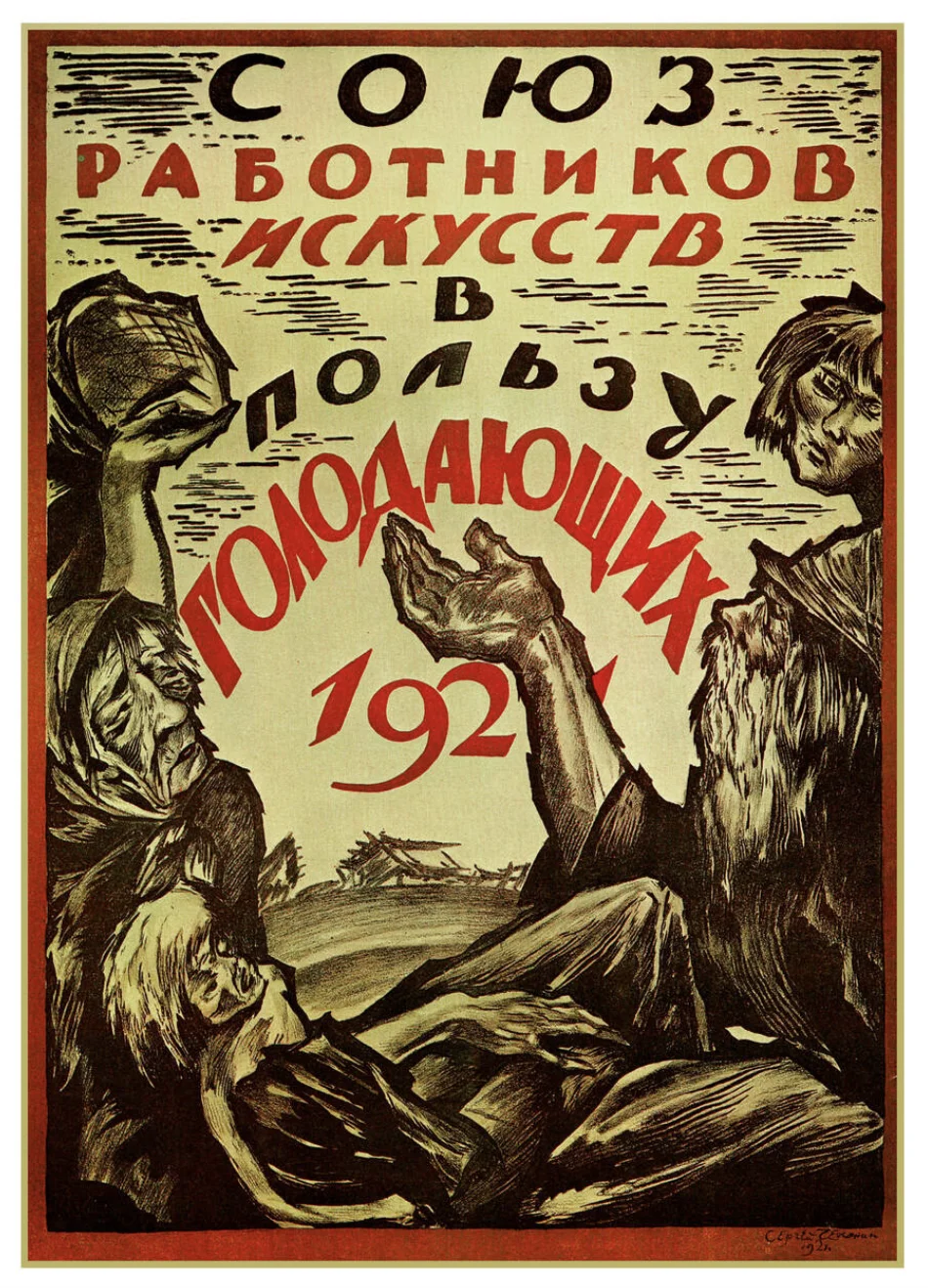

Sergei Chekhonin. Help the Starving! The Union of Art Workers Aids the Starving. Soviet propaganda poster, 1921 / Alamy

From 12 to 17 February 1922, the First All-Kyrgyz [All-Kazakh] Congress of Commissions for Famine Relief was held in Orenburg, with the participation of representatives from all the famine-affected provinces. At the congress, the deputy chairman of the Central Commission, S. Sergeev, delivered a report stating that in the Orenburg, Aktobe, Ural, Kostanay, Bokey, and Adaev districts alone, the number of starving people reached 2,653,300i

The exact figure was cited two days later at the Second Regional Party Conference in Orenburg by Seitkali Mendeshevi

According to reports from the field, people are eating roots of grasses and leaves of plants. In some areas, they are eating dogs, cats, and other small animals. Skins are being pulled from storage and used as food. Cases of cannibalism have also been recorded in the Ural province and some other areas. In famine-stricken regions, thefts, robberies, and murders have increased, and cases of insanity from exhaustion have been noted. The nomadic steppe population—the poorest Kyrgyz who lost all their livestock during the drought—suffered especially severely. Brief reports coming from the localities speak of families who, receiving no aid, quietly die in their winter camps, relying on no one. These reports are direct evidence of the scale of the disaster that has befallen the working people of the Kyrgyz Republici

On 8 July 1922, Mendeshev spoke at the third session of the Kazakh Central Executive Committee (KazCIK) of the second convocation, delivering a detailed report on the famine and the measures taken to combat it. The session concluded on 14 July, and during this time, he noted that during the peak of the crisis, from March to May 1922, the number of people affected by famine reached 2,832,000i

The famine, which forced thousands of people to wander in search of food, was brought under control thanks to the efforts of the Central Commission for Famine Relief KazTsIK) and local commissions. As a result of these efforts, the widespread famine in Kazakhstan was brought to an end from 1923 onward.

From 1930 onwards, fearing social unrest due to forced collectivization, the 1932–1933 famine, and massive peasant migration into cities, Soviet authorities launched a series of purges. Between 1930 and 1939, hundreds of thousands of people perished / Alamy

However, at the end of June 1921, a cholera epidemic, spreading from Samara, struck the Kazakh ASSR, dealing a new blow to the local population. By the end of August that year, 13,789 people had fallen ill, and 5,706 diedi

It is important to note that in 1920–21, infectious and epidemic diseases spread actively throughout Kazakhstan, including tetanus, smallpox, scarlet fever, anthrax, dysentery, malaria, whooping cough, a cholera epidemic and typhoid fever, relapsing fever, as well as tuberculosis, brucellosis, syphilis commonly known among the locals as ‘teñge qotır’, and other illnesses. According to data from 1921, 350,005 people in the Kazakh ASSR were infected with various infectious diseases.

The Famine of 1927–1934

The chronology of the famine in Kazakhstan intentionally begins in 1927. Historical records indicate that following the drought that year, the Kazakh steppe experienced a severe grain shortage, and by the following year, the first signs of widespread famine emerged. Between January 1928 and mid-1930, based on incomplete data, the population of Kazakhstan decreased by 794,400 people. Naturally, this decline was caused not only by famine in some areas but also by several other factors.

Another key element that worsened the situation was the administrative-territorial reform completed in September 1928. This reform created 193 new districts, most of which were headed by poorly educated and inexperienced personnel, mainly peasants and workers. Their frequent mismanagement further aggravated the crisis.

Seitkali Mendeshev /Wikimedia Commons

The tragedy, driven by multiple factors, unfolded at a terrifying speed. Researchers identify three main government decrees as critical: large-scale requisitions of meat, livestock, and grain, along with forced collectivization, which sparked widespread resistance and the mass slaughter of livestock. The situation was exacerbated by provocative agitation from wealthy Kazakhs and anti-Soviet groups who urged peasants, ‘Better to eat your livestock than give it to the collective farm.’ Widespread peasant uprisings and the drought of 1931–32 only deepened the famine’s devastating impact.

For example, if in 1929, the total livestock in Kazakhstan numbered 44,723,200 headsi

How the Consequences of the Famine Were Studied

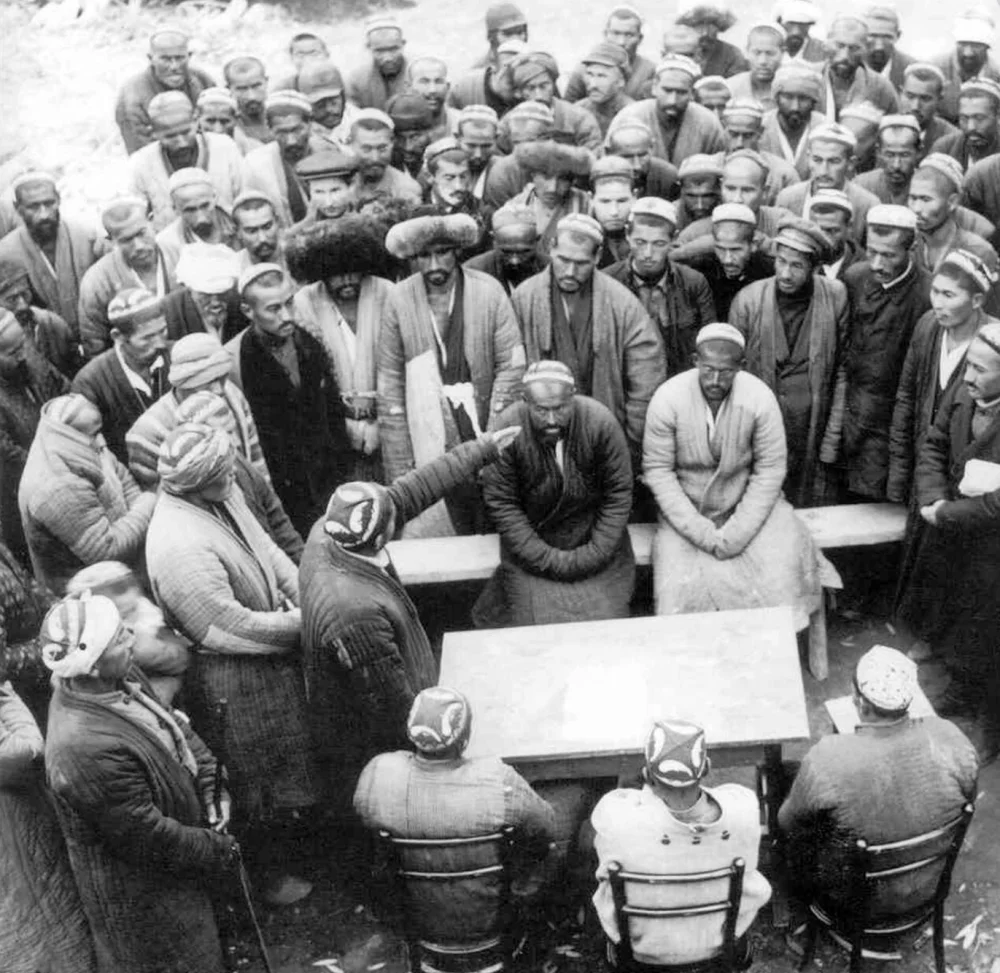

To examine the consequences of the 1931–33 famine, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Kazakh SSR passed a resolution on November 14, 1991. The resolution established a commission to study key Soviet decrees that had contributed to the crisis: the decree ‘On the Confiscation of the Estates of the Bais’ (27 August 1928), ‘On Criminal Liability for Resisting the Confiscation of Large and Semi-feudal Bais’ (13 September 1928), and ‘On Measures to Strengthen the Socialist Restructuring of Aagriculture in the Areas of Total Collectivization and to Combat Kulaks and Bais’ (19 February 1930)i

Manash Kozybayev / Kazgazeta.kz

Under the leadership of academician Manash Kozybayev, the director of the S. Ualikhanov Institute of History and Ethnology at the Academy of Sciences of the Kazakh SSR, the commission conducted an extensive study based on previously classified archives from the Joint State Political Directorate (abbreviated as OGPU), People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (abbreviated as NKVD), and Committee for State Security (abbreviated as KGB), as well as documents from other archival institutions. A scientific report was prepared based on the materials examined. According to its conclusionsi

Based on historical data, it can be said that from 1928 to 1936, the population of Kazakhstan decreased by over 2 million people, excluding natural population growth. After analyzing the available sources, the figures published by the commission of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet appears to be the most accurate. During the devastating famine, 2,200,000 people died on Kazakh land, of whom 1,750,000 were Kazakhs. However, these figures likely still underestimate the full scale of the tragedy. Much thorough and careful research remains to be done to uncover the complete historical truth.