On the surface of things, the Russian Empire claimed it was bringing progress to the Kazakh steppe. But in reality, its officials misunderstood almost every aspect of the world they encountered: the nomadic way of life, the local traditions, and even the nature of Kazakh Islam. To them, the movement of herding communities meant backwardness and that faith among nomads was purely superficial. Convinced that they were trying to ‘fix’ these flaws, imperial administrators pushed people to settle and farm, ignoring how painful the transition could be for nomads. These mistakes revealed something far deeper than mere policy failure: an empire unable to understand its own diversity. In an interview with Qalam, Ian Campbell, Professor of History at the University of California, Davis, explains how these misunderstandings shaped the fate of both the Kazakh steppe and the empire itself.

Ian Campbell / Qalam

What mistakes did the Russian Empire make while ruling the steppe?

They made several mistakes, a number of which stem from different sources. Sometimes, it was a simple lack of information, but at other times, the most important mistakes had to do with the fact that people perceive the world around them with their own prejudices. They see it through the prism of their own experiences. And that influenced very strongly the biggest mistakes that the Russian administration made during their rule of the steppe.

Imperial Russia was an Orthodox Christian nation; it had very certain, definite understandings of what religion and religious ritual should look like. It was also largely an agricultural nation. It came from a heavily forested area, where everyone was settled on the ground.

They never truly understood the nature of Kazakh Islam. A persistent misconception existed that the Kazakhs did not observe religious obligations in the same way as settled Tatars, largely due to their nomadic lifestyle and lower literacy rates, and that they were not deeply connected to the Islamic faith. This view led to the stereotype that the Kazakhs were, at heart, still pagans, merely covered by a thin, superficial layer of Islam. They were superficial Muslims.

Of course, this was not true. Yet, it gave rise to the idea that the Kazakhs could still be ‘won over’, that they were highly susceptible to different religious influences. There was a sense of struggle—either to keep them from coming under Tatar influence or to guide them in another direction. What was not understood, however, was that the Kazakhs themselves wanted Tatar mullahs and religious teachers to live among them precisely because they were already Muslims and because this met a genuine spiritual need within their community.

How did the Russian Empire get nomadic life so wrong?

They did not see that this way of life was a sophisticated and effective adaptation to the natural conditions of the steppe, rather than an inferior form of economy. Instead, they assumed that the Kazakhs remained nomads ‘out of laziness’, as if nomadism represented a lower stage of development, insisting that agriculture could, and therefore should, be practiced there.

There was also the notion that large numbers of settlers could be invited to the steppe, who would immediately establish villages and begin farming. It was believed that the Kazakhs, observing this example, would soon wish to take up agriculture themselves and that everything would naturally fall into place. What was not understood, however, was that such a transformation was not possible everywhere. The Kazakhs practiced nomadism not merely out of choice, but because it was deeply intertwined with the natural conditions of the steppe. This way of life could not simply be replaced or forcibly reshaped.

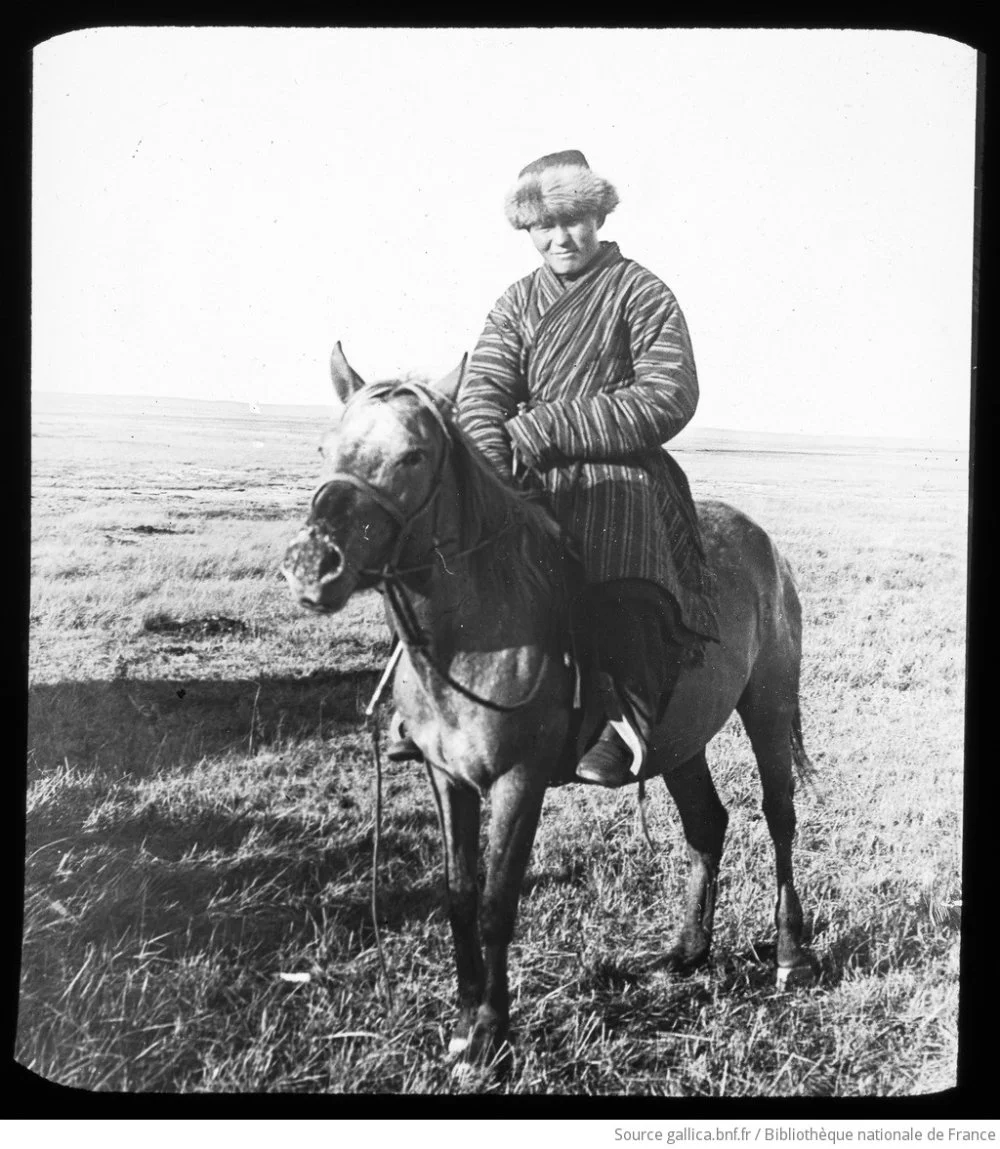

Kazakh on horseback. 19th century / Jules Marie Cavelier de Cuverville / Bibliothèque nationale de France / Gallica

And if one attempted to impose such change, it was unlikely to succeed. Moreover, it could make some people very angry. This was not merely an economic adjustment, but an upheaval of an entire worldview, of a way of life shaped over centuries. It could not simply be replaced by saying, ‘Now that someone has shown us how to farm, we’ll do that instead.’ None of this was properly understood by the empire.

There were a few specialists who argued that the steppe was indeed well suited for animal husbandry and that there was no need to impose drastic changes through resettlement. Yet, this view was far from common. The higher one moved up the administrative hierarchy, the stronger such biases and superficial attitudes became.

Mountain landscape of Kazakhstan / Getty Images

How painful was the nomads’ transition to settlement?

I sometimes wish we had better sources to fully capture this process, but it is clear that the transition was incredibly painful. When the Kazakhs chose to settle during this period, it was usually out of necessity, not desire. Sedentarization often resulted from poverty, when a family no longer possessed enough livestock to sustain long migrations, it became easier to remain in one place where fodder was still available. The trauma of this transformation, and more broadly of Russian rule, can be sensed through the poetry of the ‘Zar Zaman’ erai

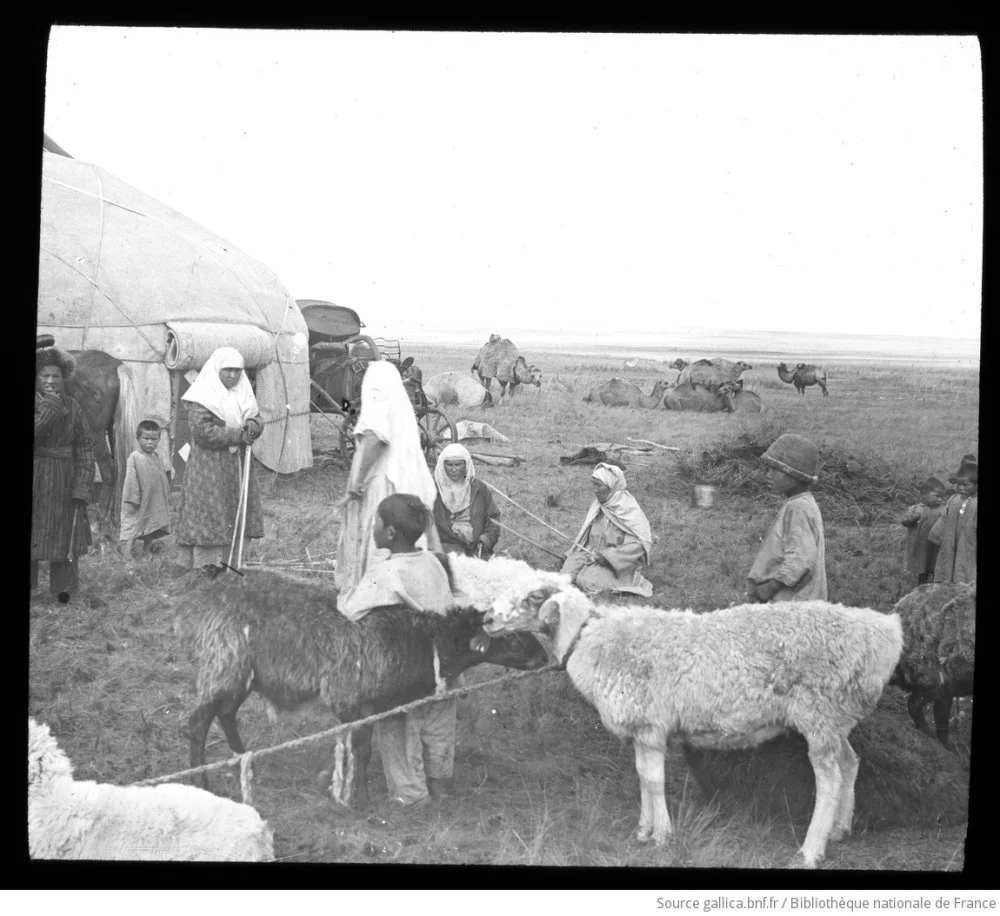

More broadly, I once worked with a student on this topic, where they were focusing on the changes in sheep herding during the era of resettlement. Kazakh pastoral nomadic life was built around a rich material and spiritual culture deeply intertwined with animals and the use of animal products. This entire system inevitably began to change when the number of livestock declined and when new economic and agricultural models emerged: systems that regarded animals in a completely different way.

Shearing the rams / Jules Marie Cavelier de Cuverville / Bibliothèque nationale de France / Gallica

How did the Russian Empire turn the steppe’s hardships into tragedy?

A major jut, or a harsh winter that led to mass livestock deaths because there was no pasture to be found, occurred in the steppe region in the early 1890s, which was around the same time as the great famine in European Russia. During this period, large numbers of involuntary settlers were displaced from European Russia and scattered across new territories. It would be particularly valuable to examine how these two events were connected and how their interaction influenced the social and economic landscape of the steppe.

I would highlight two main factors here. First, when reading about these recurring juts, such as the Qoian jyly, or the ‘Year of the Hare’, which occurred roughly every twelve years, one sees that they were understood as extremely difficult and tragic periods. Yet, within pastoral nomadic culture, there was also an awareness that recovery was possible. As long as some animals survived, they knew that the herds could gradually be rebuilt through breeding, eventually returning to their former strength and size within a few years.

Kazakh Meal, Turkestan Album, 1865–1872 / Library of Congress

Of course, this recovery depended on the nomads’ freedom to move across wide territories. With the steady influx of settlers, this freedom steadily diminished. It became increasingly difficult to reach traditional ancestral pastures or to follow familiar migration routes as new villages and farms appeared in areas that were once used for grazing. Even when the Kazakhs tried to continue their seasonal movements, they often found their paths obstructed and were forced to take longer, less convenient routes. What had once been a self-sustaining rhythm of life was slowly constrained by the expanding boundaries of empire.

Another, perhaps even more sinister aspect, was the persistence of a particular imperial narrative. Russian officials often viewed the Kazakh nomadic economy through the lens of the jut, believing that it was inherently fragile and uniquely vulnerable to natural disasters. The argument went that if the ground froze and animals could not graze, they would inevitably die, proving the superiority of sedentary agriculture, which allowed people to store grain and hay for the winter. From this perspective, nomadism appeared deficient and backward. And out of this belief grew a so-called humanitarian justification for imperial intervention. Russian officials claimed that the Kazakhs needed to be ‘taught’ how to be less reliant on nomadism, to cut hay and store it for winter, and to seek the protection and assistance of the state through various forms of aid, or ‘donations’, as they were termed in Russian.

This creates a striking paradox. On the one hand, resettlement made it far more difficult for the Kazakhs to recover from juts in their time-tested, traditional ways. On the other, imperial officials promoted the idea that resettlement itself, by taking Kazakh lands and pushing them to intensify their economy, would supposedly make them less vulnerable to such disasters in the future. This reasoning served to justify both the settlers’ presence and the broader transformation of the Kazakh pastoral economy. All these processes became deeply interconnected, forming a complex and revealing moment in the history of the steppe during the 1890s and 1900s.

Was the 1916 uprising part of the Russian Empire’s wider crisis?

It was indeed the local manifestation of a broader imperial crisis. The upheaval of 1916 in Kazakhstan should be understood as part of the wider breakdown of the Russian Empire during the Great War, the First World War. The single most important cause of the 1917 revolutions was the war itself. The connection between the Great War and the revolution can be illustrated through an image of a wooden beam already weakened by deep cracks. It is clear that the beam will eventually break, though the exact moment it shatters depends on the amount and timing of the pressure applied to it. The Great War placed enormous strain on an already fragile structure, bringing it to collapse. Even without the war, some other crisis would likely have caused a similar breakdown, but the war accelerated this process. The same pattern could be seen across other empires such as Germany, the Ottoman Empire, and Austria-Hungary, which also succumbed to political collapse under the prolonged stress of total war.

Ignacy Fudakowsky. Russian troops in Galicia during World War I. 1916 / Wikimedia Commons

The draft order that required the Kazakhs to work behind the front lines to compensate for shortages of manpower and industrial capacity was directly linked to the immense pressures that the Russian Empire was facing by 1916. Economically and demographically, the state was under extreme strain. And so, we can see the kind of fundamental stressor that produces both the revolt of 1916 and the kind of broader collapse of the empire in a similar way—it was the war.

A Kazakh family leaving for China after the 1916 uprising / Wikimedia Commons

This discussion can be taken even further when we consider what some have described as the Russian Empire’s failure to modernize, though this remains a matter of debate. At the time, one of the central ideas driving reform was the shift toward private land ownership and the intensification and modernization of agriculture. This approach was closely linked to the belief that Siberia and the Kazakh steppe had to be colonized and that all the so-called productive forces of the empire needed to be fully mobilized if Russia was to enter the twentieth century as a modern power.

The resettlement policy, which lay at the heart of the 1916 uprising, emerged directly from these ambitions. It was part of an effort to address what was already seen as the deep structural weaknesses of the Russian economy. In this sense, both the resettlement drive and the uprising it provoked were closely tied to the broader struggle of the empire to overcome its internal limitations and adapt to the pressures of modernity.

Was Nicholas II to blame for the fall of the Russian Empire?

This is a difficult question. Nicholas II was, in many ways, unfortunate to be the one holding the bomb at the moment it exploded, though it had been ticking for a long time. The structural weaknesses of the empire predated his reign, yet his actions, or more precisely his lack of decisive action, played a role in accelerating its collapse. There were certainly many things he could have done differently. One can imagine several possible scenarios in which the empire might have endured longer: for example, if the war had been managed more effectively, or if Nicholas had, at critical moments in 1915 and 1916, cooperated more closely with those segments of society eager to support the government in its wartime effort. Instead, he hesitated for too long, missing opportunities to strengthen the legitimacy and resilience of his regime.

Nicholas II, V. Fredericks, and Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich at the Stavka of the Supreme Commander. 1915 / Wikimedia Commons

Nicholas certainly made mistakes, particularly in how the war was conducted. He bore responsibility for critical failures of leadership and for the deeply flawed culture that developed within the Imperial Army by the time of the Great War. Had these aspects been handled differently, the outcome of the conflict might have changed as well. Returning to the earlier metaphor of the cracked beam, one could say that with better decisions, some of the pressure might have been relieved, allowing the system to endure a little longer before breaking apart.

In that case perhaps, the events of 1917 might not have taken place, and a different kind of transition might have occurred. Yet, it seems very likely that Nicholas, regardless of the outcome of the Great War, was destined to be the last tsar to hold such absolute power. He stood at a crossroads, facing a historic choice: to guide the transformation that was already unfolding or to resist it entirely. Unfortunately, he proved unable to recognize that these changes were inevitable. He saw himself as bound by God and history to preserve the autocracy, refusing to yield or adapt. And this was precisely the wrong approach.

Nicholas II among officers aboard the cruiser Rossiya. 1915 / Wikimedia Commons

What were the lasting legacies of the Russian Empire?

This is a good question. Several legacies of the empire’s fall remain deeply significant for both Russia and Central Asia. One of the most important is the continuation and transformation of the settler movement into Central Asia, particularly in Kazakhstan. After the Civil Wari

The expansion of settlements created the enduring idea that these regions were not only Central Asian but that they also carried a distinctly Russian dimension. This perception was reinforced by multiple waves of migration and by the Soviet state’s efforts to develop the steppe as part of its broader project of building a unified, industrial, and ‘modern’ socialist space. The legacy of this process is still visible today in the demographic, cultural, and linguistic landscape of Kazakhstan and across Central Asia, where questions of identity, belonging, and historical memory continue to reflect the complex inheritances of both empire and Soviet power.

Vittoriano Rastelli. Almaty, May 1969 / Getty Images

This settler movement can also be seen as an early prelude to the Soviet Union’s later policies of population redistribution and land development. Northern Kazakhstan in particular illustrates this continuity because it was both the center of Russian settlement during the imperial period and the heart of the Virgin Lands campaign decades later. This region consistently remained the most densely populated by non-Kazakhs, reflecting a long process that began under the Russian Empire and was later institutionalized by the Soviet state. The roots of these demographic and agricultural transformations reach back to those first waves of resettlement, which laid the groundwork for the social and economic patterns that would shape northern Kazakhstan throughout the twentieth century.

Among the legacies of the empire’s collapse, the 1916 revolt and its eventual failure can, in some sense, be seen as one of the sources of the emerging idea of Kazakh nationalism or Kazakh identity as a political force. It was not the only factor, of course, but it was certainly part of it.

Without going into too much detail, it can be argued that the specific way in which the empire collapsed had lasting consequences. The 1916 revolt, especially in regions such as Torgai and Semirechye (Jetisu), was marked by extreme violence and widespread destruction that deeply affected both the people and their environment. These events clearly influenced the course of political and autonomous movements in the region between 1917 and 1920, shaping the circumstances that eventually led to the establishment of Soviet power.