Utagawa Hiroshige. Portrait of Murasaki Shikibu. 19th century/Alamy

Why in patriarchal Japan did they rejoice more at the birth of a daughter? What do the diaries of the Heian period ladies tell us? How many logograms should a respectable woman know? Qalam answers.

Perhaps every human society strives to develop based on unified sociological and biological principles, but as we know, the results of this development can vary greatly. It’s fascinating to observe how these principles and factors shape the trajectories of societies. Take, for example, Japan. This country, by virtue of being an archipelago, is geographically isolated from common civilizational paths. Whatever Chinese and Korean travelers brought on their ships was reinterpreted and twisted in a purely Japanese manner, and for centuries, Japan developed completely autonomously, simmering only in its own juices. As a result, a world that is alien to the Western world was created, leaving Europeans astonished by local customs. Even the platypus, when you think about it, is less intriguing and shocking than what grew on the Islands of the Great Dragon, especially when we talk about the Heian period.

This period, named after Heian (now Kyoto), the capital of Japan at the time, lasted from about the eighth to the thirteenth centuries. This was a period when Japan aimed to limit outside influence as much as possible. It gradually distanced itself from mainland culture, a process that culminated in the delicate, lush, impossible cultural blossoms of the Heian era.

Portrait of the famous Japanese writer of the Heian period, Sei Shonagon/Getty Images

The Heian era also witnessed the emergence of remarkable literature, notably in the form of a modern psychological novel exploring emotions, upbringing, and relationships. Though we should be more familiar with ancient Roman literature, which is sometimes striking in its modernity, we understand it only through its rational foundations as it is close to our beliefs and thoughts. In contrast, the Heian diary—known as nikki or zuihitsu, a record of personal experiences, feelings, and all sorts of nonsense and fleeting thoughts that come to mind during the day—could as easily have been maintained by any modern woman from Almaty, Moscow, or Paris as it was in the Heian era. In addition, the Heian novel, monogatari, had no equivalent in Europe or anywhere else in the world until the appearance of novels like Pride and Prejudice almost a millennium later. This is because these novels are not so much about events as they are about psychological analysis.

Interestingly, the majority of works of Heian literature came from the pens of women. Moreover, men who wrote at that time often used female pseudonyms and narrated from the perspective of women, like George Sand and the Bell brothers, albeit in reverse.

‘And now I, a woman, who decided to attempt to write what is called a diary, they say men keep them too,’ begins Ki no Tsurayuki, the great Japanese poet and compiler of classical poetry anthologies, in his famous The Tosa Diary. He wishes to take on a female guise because his text is written in syllabic script, almost without the use of kanji hieroglyphs, similar to the writing style of women who crafted literary works for women. This declaration aligns with the way all renowned Heian literature was written.

Poet Ono no Komachi washes a manuscript. A popular subject in Japanese prints, based on the play of the same name/Superstock

It is because of the literature from the long-gone Heian period that still endures today in all its strange brilliance that we can understand where such a plethora of women creators came from. Alas, little remains of the Heian literary splendor: a few dozen major works by a couple dozen authors and some fragments and quotations. Through numerous references to various texts, which are lost now, we can grasp the extent of what has been lost and see that what remains is only a pitiful handful from a vast number of works created in that era. But it is at least something.

‘If Only I Had a Daughter…’

Contrary to the prevailing left-wing perspectives today, in many cultures,the birth of girls was often celebrated with the same joy as the birth of boys. However, the reaction could vary based on the prevailing circumstances, and while boys were preferred as future providers and protectors in many different periods, this was not the case in Heian.

The only birthing rooms where the birth of a male child was highly desirable were the birthing rooms of the Imperial Palace. In all other families, parents primarily wanted daughters, especially the aristocrats and the middle class. It was the girl, not the boy, who presented the chance for significant improvement in the family's status.

Certainly, according to Buddhist customs, women were considered secondary, weak, and subordinate beings. This was a norm that Heian ladies themselves loved to lament, expressing regret about the supposed sinfulness of their female essence at every opportunity. However, they would eagerly prefer having a girl if given the choice, and were quite content to discard a boy in the rice fields.

Unknown author. An engraving shows Murasaki Shikibu's rival Sei Shonagon. 1760s/Superstock

This situation arose due to a significant scarcity of girls in the population, which had understandable causes. First, during the Heian period, Japan was not at war—there were periodic outbreaks of discontent in the provinces, and the Ainu and other ‘local savages’ sometimes were the source of some trouble. However, all these were local conflicts that did not require a strong army response or special bloodshed. Therefore, young men here rarely, if ever, died in wars, while the women died during childbirth no less often than in other parts of the world. This was exacerbated by the largely rice-based vegetarian diet that contributed to developmental abnormalities. Over the last fifty years, thanks to changes in the national diet, the average height of Japanese women has grown by almost 20 centimeters and there has been a significant reduction in hip joint dysplasia.

Second, traditional matrilineality was deeply ingrained in Japanese families, where a woman typically remained in her parents' home her entire life, and her children would stay in the same family. The man would only visit his wife—or wives, as monogamous marriage as such did not exist in Japan for a very long time. It only began to appear during the Heian period and even then, it had distinct characteristics, but we will return to this later. Consequently, many men found themselves without wives or girlfriends as women chose partners from the most successful, noble, and wealthy men, often preferring to be the fifth wife of a taisa (second commander-in-chief) rather than the only and unique wife of a low-value man of the eighth rank.

6 girls in the image of "6 immortal poets" who created in the waka genre in the IX to X centuries/Getty Images

Additionally, considering that respectable women had access to a vast number of maidens and servants, who were also removed from the marriage market, finding a wife in Heian Japan was a very difficult task. As we mentioned before, there were simply not enough girls for all the suitors. Due to this scarcity, peasants sent their daughters to the capital, artisans to the lords, the lower aristocracy to the upper aristocracy, and the upper aristocracy to the Imperial Palace, which at that time was truly a women's kingdom.

Let us also consider the prevailing rules of the time: a son could not have a higher status than his father, and the same was also true for a grandson and his grandfather. That meant that if the men in a family could only reach the sixth rank in their military service, no matter how talented you were, you would never get the fifth rank and increase your income because it would be a violation of tradition and thus a scandal. But if you were a girl, a beautiful, talented girl who had touched the heart of a nobleman? Well, your deceased great-grandfather could then be granted a posthumous higher rank by special decree, so that it would be acceptable for that nobleman to have offspring with you. Thus, your entire family would climb the social ladder, much to the envy of your jealous neighbors.

A significant number of Heian-era novels contain stories of how a poor family (usually of noble origin but who had fallen into decline in the provinces) produced an impeccable beauty who captivated the heart of a high-ranking courtier. The story would unfold with the beautiful daughter and the courtier ending up in the Imperial Palace, eventually leading to her becoming the mother of emperors. Such strokes of luck are exemplified in tales like that of Lady Akashi from The Tale of Genji or the beautiful Ochikubo from the eponymous novel.

Illustration from a Japanese scroll depicting the adventures of a Heian period statesman. 12th century/Getty Images

During that time, even without considering entry into the imperial court, if you had many beautiful and well-educated daughters, you could establish connections with many noble families and gain leverage with high-ranking officials in the state. In Utsuho Monogatari (The Tale of the Hollow Tree), another classic work, the plot revolves around a nobleman who has eighteen daughters from different wives, all renowned for their beauty and surrounded by suitors. In the end, the cunning nobleman controls almost all state affairs because if something goes wrong, he could simply take his daughters and grandchildren from their husbands’ homes. As we already know, families in Heian Japan were matrilineal and the husbands’ rights were negligible—everything was decided by the grandparents. You should not have offended your grandfather, Mr Minister! Now you will wet your robe sleeves with tears of repentance and ask for forgiveness!

This is why Japanese aristocrats went to great lengths to seduce the most famous, talented, and celebrated beauties so that they would give birth to many daughters, initially surrounded by the fame of their mothers. Boys were not particularly desired, or at least not in large numbers, as this excerpt from Utsuho Monogatari shows us:

‘How can you treat your son that way?’ Nakatada was surprised. ‘My daughter has just been born, and I immediately held her to my chest.’

‘If only I had a daughter like yours…’ sighed Sudzusi. ‘My son won't be better than me. And if he is even worse than me, what can we hope for? If I had a daughter, I would teach her to play the koto, I would give her various wonderful things and happily anticipate how she would serve and shine in the palace. I have a storeroom full of treasures necessary for a girl.’i

The Precious Hidden One

The birth of a daughter was a joyous and much anticipated event in Heian Japan. The following extract from Utsuho Monogatari makes it clear how the parents and family of a girl child reacted on her arrival:

Nakatada’s mother carefully wiped the newborn, cut the umbilical cord, wrapped her in the pants that Nakatada gave to her, and took the baby in her arms. Nakatada, kneeling next to the canopy behind which his wife lay, began to plead,

‘Give her to me first.’

‘What are you thinking?’ exclaimed the old lady. ‘How can you take the baby outside!’

Remaining in the same place, Nakatada pulled the sheet over his head and took the baby in his arms. The girl was very big and held her head well. She was very beautiful and shone like a precious stone.

‘She's so big! That's probably why my wife suffered so long,’ he said, pressing his daughter to his chest.

‘Let me see her, let me see her!’ Masaori said, approaching him.

But Nakatada replied, ‘I won't show her to you right now, no matter what.’

‘Are you already hiding your daughter?’ the other laughed.i

The seclusion or confinement of women in Japan differed greatly from the traditions of a gynaeceum or harem, or the female quarters of Chinese homes. Japanese women, especially during the Heian period, were not hidden from public view. Girls from ordinary families played in the streets with boys, peasant women both often dressed like men and behaved similarly to men, city women traded in shops and worked to attract customers, and female servants walked the streets without hiding their faces or figures.

It was a completely different story for a girl from a noble or aspiring noble background, particularly one groomed to be a beauty. All the girls in the same family were not treated equally—there were some who enjoyed considerable freedom, while others were veiled in front of even their own brothers, grandfathers, or grandmothers.

Katsushika Hokusai. Portrait of Sei Shonagon. c. 1820 /Getty Images

It was commonly believed that a stranger’s gaze was not only indecent but also destructive to perfect beauty. The less people looked at a woman, the less she would get sick, the brighter and more delicate her beauty would be, and the slower she would age. If we recall that the Heian period was a time of endless cold epidemics and widespread tuberculosis, this superstition may contain a kernel of truth.

Some young girls’ quarters had additional curtains around the platform on which she spent most of her time. Low tables for writing, eating, and other activities were placed next to her bed. Directly in front of her was a special ceremonial curtain on a pole with a crossbar—only her parents, sisters, and closest maids could peek behind this curtain. Moreover, the girl was encouraged to cover her face with a fan or sleeve even during interactions with close relatives. If the girl went to attend a ceremony, to a temple, or to visit someone (a very rare event that only occurred a few times a year), her path to the carriage was covered with shields and screens, blankets were carried around her, and the carriage was carefully covered with curtains.

Such a girl spent most of her time sitting or lying down, as standing upright or walking was considered almost indecent for a noblewoman—she moved around her room by sliding on her knees. Of course, she sometimes had to stand on her feet, but it was better if no one caught her doing so. In The Tale of Genji, one of the heroes falls in love with a young girl whom he happened to see standing upright in the middle of a room. For a European, grasping the impropriety of such a sight might be challenging unless one envisions it as akin to an aristocrat encountering a princess crawling on all fours—that is roughly the effect.

There were many restrictions on these young girls during that time. A girl could only admire the flowers in the garden through a slit in a curtain covering the sliding screen door. Or she could inhale their scent at night, when the curtain could be completely removed, to enjoy the full moon, with the lamps turned off. In the darkness, no one could see her beauty, and so she could be a little less careful.

Every Effort Was Devoted to Her Upbringing

However, the heiress of a Heian family did not have to languish behind curtains, as she was educated from a very young age. Her parents were directly involved in her teaching, as well as those who, in the translations of our days, are referred to as ‘servants’ in the case of a noble family or ‘ladies-in-waiting’ at the imperial court. Yet, given their roles, it would be more accurate to term them governesses and companions. True ‘servants’ and commoners tasked with menial chores, like floor cleaning and chamber pot-carrying, weren't permitted to approach these beauties too closely.

Illustration for Murasaki Shikibu's (978-1031) novel "The Tale of Genji". 11th century/Getty Images

Even a girl from not a very noble family had a typical entourage. She would have one or two wet nurses who would breastfeed her until the age of at least seven or eight. Since it was considered beneficial for little girls to drink milk, and Japan did not bother with dairy farming, bulls were raised solely as draft animals. The idea of drinking cow's milk was regarded by the Heian people in the same way we would react today to being offered pig's or dog's milk, for example. In addition, there were several ‘girl servants’ in the young girl's chambers, her peers who would study and play together with the young mistress. There were also older ‘servants’, usually talented musicians, skilled calligraphers, capable poets, and artists.

The girls would play with dolls, raise pet birds, and listen to fairy tales and songs while absorbing the basics of proper behavior, rituals, norms, and how to speak properly. At the age of four or five, they began to be taught reading and calligraphy, and music a little earlier. By the age of seven or eight, a girl would have firmly grasped the syllabic alphabet, followed by the study of thousands of kanji characters, considered the ‘true signs of male writing’, although there were certain nuances involved. Formally, the knowledge of kanji hieroglyphs was considered inappropriate for women, and they were discouraged from boasting about their proficiency in kanji characters or Chinese literature. Informally, however, a girl could not become a good poet without such knowledge, and so it was taught to her under a great deal of secrecy. Even the empress, who was supposed to know at least the basic historical Chinese works by rank, studied these works with her close ladies-in-waiting in conditional ‘secrecy’, away from the eyes of other attendants. Therefore, in their poetry, women only hinted at their knowledge of kanji hieroglyphs or famous lines from Chinese classics, while those who boldly used kanji hieroglyphs in their writing were ridiculed as arrogant braggarts or pedants without taste, tact, or education.

An educated girl during the Heian era was expected to have memorized the complete anthologies of Japanese poetry, the Kokin Wakashu and Manyoshu, which contained thousands of tanka poems. She was also required to be knowledgeable in a plethora of other literature, play at least one stringed instrument (but preferably three or four of them), write in a graceful hand, and be able to sketch delicate ink drawings to adorn her letters. She was expected to select layered silk garments appropriate for the occasion and season, understand the basics of chemistry since the art of making incense for the burners was considered a necessary feminine virtue, schooled in religion and etiquette. And considering that by the age of twelve or thirteen, she was already a potential bride, she had very little free time.

Katsushika Hokusai. Two Heian ladies watching a parrot. 1821/Getty Images

But the most important thing that was required of her was the ability to improvise and compose tanka poetry on the spot. Here we begin to enter the realm of the incomprehensible as the modern reader who does not know Japanese usually has little idea of the significance of these monotonous verses with their eternal wet sleeves, crying geese, and blooming plum blossoms. Anyone can write five lines of such emptiness.

But this verse is all about kakekotoba, a technique used to craft multi-meaning puns in Japanese poetry. Translators often refrain from attempting to translate these puns directly, instead opting to convey only the surface meaning of the verse or providing extensive notes, sometimes spanning several pages, for each poem.

What is written with syllabic characters can also be written with hieroglyphs, and the hieroglyphs can be read in different ways, depending on the order of the characters and the way they are pronounced. It is easier to explain this with an example, although most languages in the world are not suitable for kakekotoba. But you can try twisting them once, as in the example below.

Letter

from fishing we returned

was the shore waiting for me

with the soul open to the mountain?

This is the superficial interpretation of the poem. The fisherman is returning home, enjoying the landscape and talking to the mountains and the shores. Now, by altering the emphasis (indicated by capitalized letters) in certain words and rearranging the order of those same letters, the meaning of the text changes.

Letter

The words returned

Did you take care of me? Did you wait for me?

Choking my sorrowfulness having read [the letter].

That’s quite a different picture, isn’t it? This demonstrates precisely what kakekotoba entails, serving as the foundation of all Heian poetry—a sophisticated and clever pun with two or three layers of meaning.

In your ‘response poem’, you had to, after receiving a sheet of paper with boring hints about some purple flowers and the roots of Acorus that gave you no clue what the sender was referring to, quickly come up with a similarly witty pun. Fortunately, there would usually be a smart servant-instructor at hand who would immediately guess which classical tanka this reference was from and how the author of the letter had played with it here.

Of course, only the most talented girls with the quickest minds and the best grasp of language and ideas could truly play these games. The rest relied on their ‘impromptu’ compositions from learned anthologies, often even having their accompanying ladies compose for them. However, such subterfuge could not fool discerning observers for long.

A Time to Love

When a girl turned twelve or thirteen years old, she began to attract interest on the marriage market. Although she continued to spend a secluded life, her chamber now began to resemble an office as potential suitors began to send her letters. Letters also came from ladies from related families, sisters of potential suitors, family friends, and even casual acquaintances. Receiving about a dozen or so letters every day was a perfectly modest norm.

Sending a few lines of poetry to a lady, even if she was married or a nun, was perfectly normal if it was purely business-like and did not contain any mention of love or other foolishness. For example, it was considered acceptable to send a message like: ‘Congratulations on the ninth day of the ninth moon! I am sending you two pheasants as a gift, and here are a couple of verses on this occasion.’ But a man could also send love letters to a girl even if he had no chance or desire to marry her—the letters were just a trifle that did not oblige anyone to anything, like dancing at a ball among Europeans (the Heian people would have been surprised by this strange custom).

Murasaki Shikibu. Japanese poet and writer/Alamy

A girl could reply to a letter or she could ignore it. If she never replied to anyone, rumors began to circulate that she was insensitive and talentless, and so attentive parents and responsible servants watched over the girl's correspondence to ensure that she replied to the right people in the right way. At the same time, servants who were invested in the girl's marital success spread rumors about how incredibly beautiful, refined, and peerless the young lady was.

If these stories were occasionally accompanied by response letters containing exquisite poems written by the girl herself (which could quickly be verified as the handwriting of all her servants could be easily obtained and compared to her writing), there would be admiring conversations about the girl.

Illustration for "The Tale of Genji". 17th century/Getty Images

A union was acknowledged after a man had secretly made his way into a girl's room for three consecutive nights and spent the night with her, sneaking away before dawn and sending her grateful poems. On the third night, he stayed openly and was formally greeted by his new relatives in the morning. Of course, in most families, such affairs were not allowed to get out of hand, and relatives always arranged things so that the right man was to sneak into the garden and no other person was permitted.

However, if the girl's parents had serious ambitions but found no suitable suitors when she started receiving letters, they would send her to serve in the Imperial Palace, which was the largest network of acquaintances in Heian. At the palace, the courtiers engaged in endless courtship rituals with the maids of honor, which often resulted in romantic and matrimonial alliances within the imperial court.

Girls who were intended for the emperor himself, of course, were in a special position, under strict supervision. Yet, even they often managed to get into trouble before any arrangement with the emperor or heir to the throne could materialize. In such cases, aspirations for any high position were already out of the question as the emperor having a wife involved in scandal was out of the question. However, they would remain as ladies of the court, enjoying a pleasant life in the company of educated friends, indulging in music, poetry, and conversations as well as love affairs with different courtiers. Occasionally, they would leave to give birth at home, making their parents happy with new grandchildren, whom their fathers financed. For most girls, however, their time in the palace was brief, lasting only a few weeks or months before they managed to catch the eye of a suitable official and marry him.

Choose Who You Want to Be

After marriage, a woman in the Heian period had many possible fates. She could stay at home for practically her entire life, occasionally meeting her visiting husband, and spend her time composing elegant poems about how that bastard made her suffer, jealous and languishing, because of his recent dalliances with some lady from the sixth district, known only to the evil spirits. The wonderful Diary of the Ephemeral Life by Michitsuna no Haha is dedicated to the similar suffering of a jealous wife. The author was the wife of the courtier Fujiwara no Kaneie, who chronicled her unhappy fate for many years, constantly exchanging elegant letters with her husband’s other wives. Together, they artistically condemned the fickle nature of their scoundrel husband, especially when he acquired a new passion.

From Michitsuna no Haha to the main wife:

Broadleaf rice,

As they say, was planted.

Even there, at your place.

So in which swamp

Does it take root in?

From the main wife to Michitsuna no Haha:

Yes, they planted

The broadleaf rice,

And somewhere in a swamp it rooted.

But I thought

That swamp belonged to you!i

How elegant, isn’t it? So much more sophisticated than saying, ‘I believed he was with you, but he's gone off with someone else!’ with the reply coming back, ‘No, he hasn't been here for ages. I thought he was with you!’

One could have ended up being that very ‘main wife’, or the Lady of the Northern Chambers, in which case the young woman would move into the man's home, occupy the main chambers, and oversee his household. Such a fate was considered enviable, but somewhat trivial, as it did not involve the refined, graceful experiences that enriched a woman's fate and soul. However, if we are talking about noble families, the absence of a main wife would undoubtedly be rectified by the husband, who would not hesitate to populate his estate with wives of a lower rank, thus creating a spirit of healthy and creative female competition. This competition was highly valued by Heian courtiers as it enlivened everyday life, turning it into an endless series of intrigues and interesting events.

Unknown artist. A dancer with a fan. 17th century/Superstock

It was also acceptable to part ways with one's husband and enter a relationship with another, being considered simply another aspect of life. Alternatively, one could choose to remain in proud independence, embarking on pilgrimages to monasteries, visiting the country estates of friends, and attending ceremonial events in the provinces. They traveled through Japan with a retinue of servants, soaking in hot springs, hiking mountain trails, and enjoying almost complete freedom that women who had finally shed the yoke of ‘hidden beauty’ were entitled to. Moreover, the majority of landholdings, money, and real estate in Heian Japan, as was the rule in a matrilineal system, were in the hands of women. As the saying went, ‘As the mother is always known, inheritance goes from grandmother to granddaughter, as men will squander everything on other women and their children from other marriages.’

Of course, the Heian period could not last forever. This haven of culture and refinement, which had never known war or even the death penalty—if only a few years of exile was the punishment for seducing the emperor's concubines, one can imagine the leniency of Heian law—lasted incredibly long. The aristocrats, who crowded the capital, practicing calligraphy and music, gradually ceded power over the country to rough and undeveloped ‘servile people’, who eventually took control of the provinces and neatly sidelined the imperial court to organize their own government. We know these ‘servile people’ as the samurai, and they brought a completely different history and set of customs to Japan, decisively changing everything, including the position of women.

Today, only some exquisite literary works remain of this period, offering glimpses into the unique world of Heian Japan.

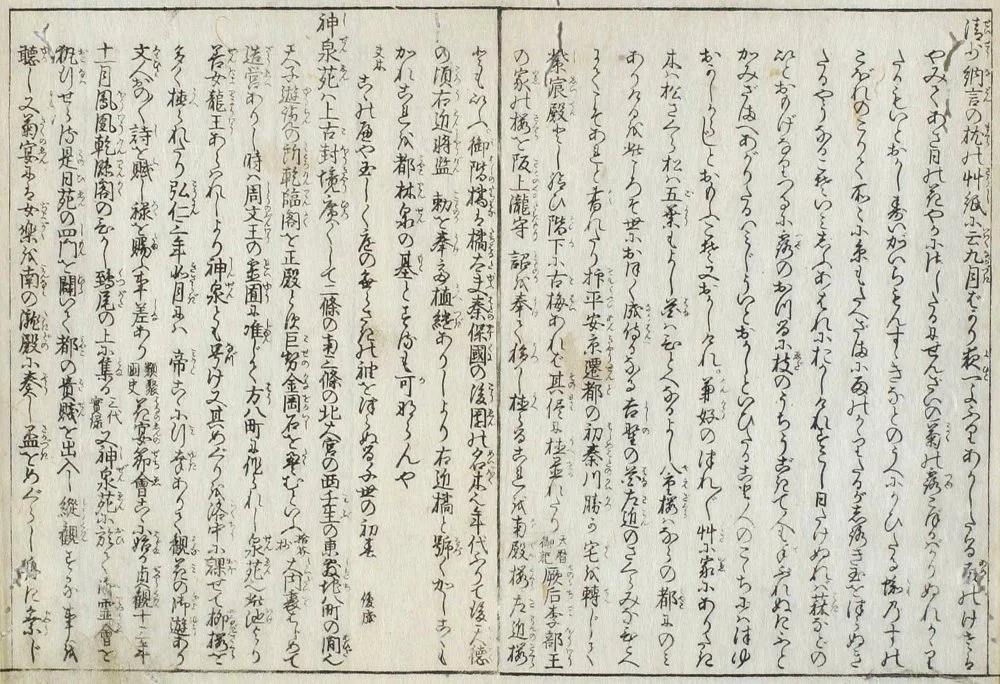

Manuscript text of "The Pillow book" Sei Shonagon's major work/Getty Images