Did you know that carrier pigeons today go back to rock pigeons, famous for their innate ability to return to their nest, also known as homing. Modern pigeons can travel more than 1,000 kilometers and reach impressive speeds of over 90 kilometers per hour. However, these figures are the result of training that undoubtedly dates back many years.

An Old Friend of Man

The pigeon (dove) is a frequent hero in many mythological stories. The bird is often identified with specific gods and goddesses (for example, Ishtar, who was popular in Mesopotamia or the Greek Aphrodite), and some of these images anticipate the postal specialization of the ‘Bird of Peace’. It is believed that the oldest depiction of the messenger pigeon can be found in the famous epic of Gilgamesh (the oldest stories of which date back to the third millennium BCE), which retells the myth of the flood and a kind of predecessor of Noah called Utnapishtim. In this version of the story, as later in the Old Testament texts, the bird was used as a scout to see if the water had begun to recede.

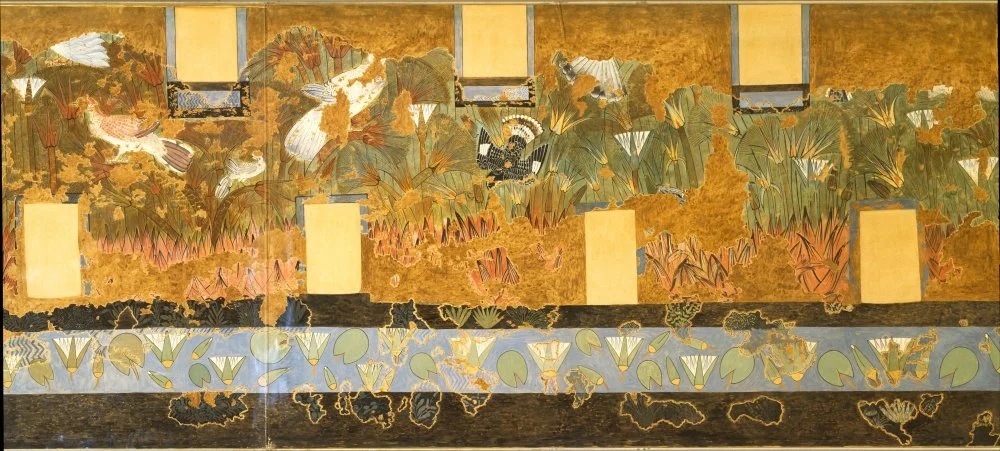

Rows of birds, detail of a painted relief, east wall of the Chapel of Ptahhotep, mastaba D64 at Saqqara (Unesco World Heritage List, 1979). Egyptian Civilisation, Old Kingdom, Dynasty V/Getty Images

Archeological discoveries from Egypt and West Asia show that pigeons were among the first animals domesticated by man and the first domesticated bird. For example, in the area of the ‘Fertile Crescent’,i

Akkadian cylinder-seal impression of the scribe Adda. It represents a new year ritual, and from left to right are: Ninurth carrying a bow, Ishtar with wings, Shamash with sun-bird and saw, and Ea, 22nd century BC/Getty Images

In the culture of ancient Mesopotamia, images of the pigeon are found on tablets and in the form of terracotta statuettes from about the middle of the fifth millennium BCE. However, it is believed that the birds were not initially bred for postal purposes. Researchers jokingly compare the pigeon in its various uses to a Swiss Army knife, known for its versatility due to its large number of blades. In fact, these feathered pets were not only eaten; their droppings were used as fertilizer. Later, these birds showed the ability to learn complex tasks, including, at a certain stage, the transportation of small objects.

The Origins of the Pigeon Post

Since ancient times, pigeons have been able to carry messages over long distances. For example, some sources report that homing pigeons were bred during the reign of the first Egyptian pyramid and the founder of the Third Dynasty, Pharaoh Djoser (twenty-seventh century BCE), who allegedly used them to send messages about future attacks on the kingdom by neighboring tribes. Artifacts attributed to the reign of the pharaoh have been found in both the Nile delta and Upper Egypt.

Thus, in one way or another, the tradition of domesticating pigeons on the banks of the Nile dates back to ancient times. As early as the middle of the second millennium BCE, many instances of the image of this bird have been found in Egyptian art. Perhaps the most famous of these is a fresco discovered during excavations at ancient Akhetaton, the capital of Pharaoh Akhenaten, the mid-fourteenth-century-BCE reformer.

Facsimile painting from the 'Green Room' in the North Palace at Amarna/Wikimedia commonsFacsimile painting from the 'Green Room' in the North Palace at Amarna/Wikimedia commons

His reign is associated with the dramatic, remarkable flourishing of Egyptian art. A detailed landscape was found in the ‘Green Room’ of his palace, depicting, among other birds, several blue doves. Ornithologists note that these birds do not like riverbanks and swamps, preferring rocky terrain, which means that they are unlikely to be in these areas by accident. Colin Jerolmack, the author of The Global Pigeon, describes a similar image in Akhetaton: a flock of pigeons being released from their cage only to return later. The oldest pigeon houses found by archeologists in Amarna (a modern settlement on the site of ancient Akhetaton) date, however, only to the turn of the millennium.

Typical pigeon houses, pigeon lofts in towering structures, location unspecified, Egypt, circa 1962/Gunter Reitz/Getty Images

Much more information about the use of carrier pigeons can be found in texts from classical antiquity. For example, there is evidence that the birds were used by participants of the ancient Greek Olympic Games. It is said that the athletes would bring pigeons from their hometowns and villages, which they would use to send back news of the games, especially about their victories, to their countrymen.

The Roman scholar Pliny the Elder discusses the subject in particular detail in his Naturalis Historia (Natural History). Among other things, he describes an effective system of transmitting messages devised by one of Caesar’s assassins, Decimus Junius Brutus. At the same time, other authors also record that pigeons were used by Julius Caesar himself during his time as consul in Gaul to send dispatches to Rome.

Aphrodite. 450 - 425 BC/Neues Museum, Berlin/Wikimedia Commons

In the Middle Ages, European authors did not lose their interest in pigeon mail, but increasingly associated it with the culture of the East. There is evidence in various sources of mail birds being used by the rulers of the Middle East and North Africa. For example, Nūr al-Dīn of the Zengid dynasty established air communication between Baghdad and Syria under his control in the mid-twelfth century. Two centuries later, the Spanish traveler Pedro Tafur described a similar system in late medieval Egypt. It is worth noting that in the European sources of that time, the authors present carrier pigeons as a strange custom of foreign culture. They seem to perceive no continuity with the ancient tradition of using these birds at all.

J. E. Millais: The Return of the Dove to the Ark (1851)/Ashmolean Museum, Oxford/Wikimedia Commons

The Pigeon in the Service of War

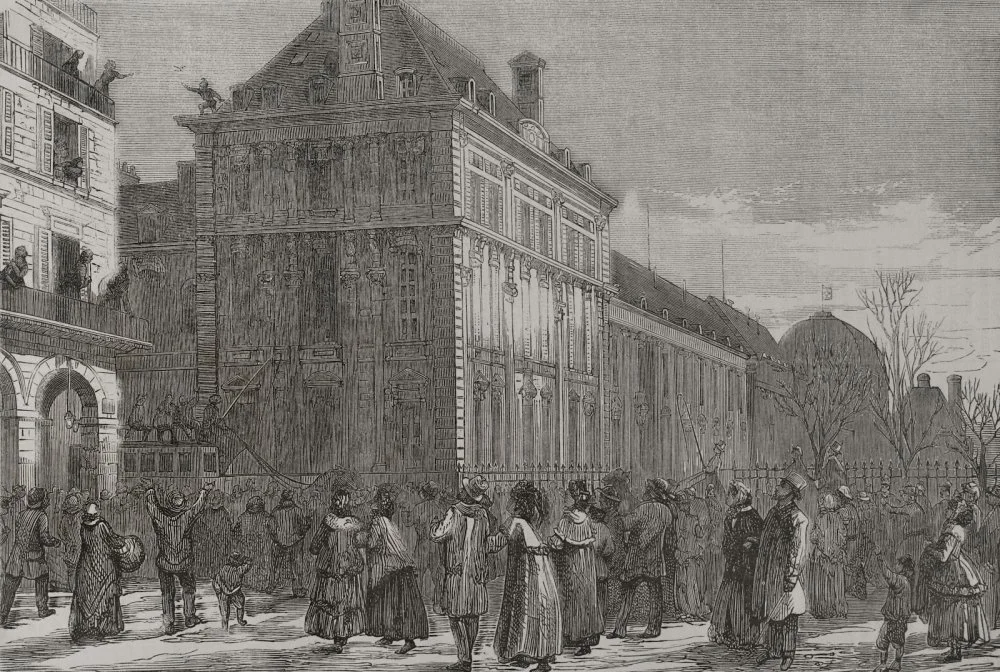

A new, and perhaps the first truly mass, interest in feathered mail in Europe emerged with the events of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. This time, the appeal of this ancient tradition was forced upon the French because the German siege of Paris essentially interrupted telegraphic communications for the inhabitants of the capital. A Mr Foumal-Delegni shared his enthusiastic observations from the pages of an information pamphlet with the readers: ‘The speed of their flight is amazing: a letter sent from Perpignani

Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871).Arrival of a homing pigeon in Paris during the siege. Engraving, 1871/Alamy

Carrier pigeon was used in the occupied city both for the transmission of strategic information and private correspondence. A special pigeon post office was set up, from which more than 15,000 pigeon letters were sent to different parts of the country. The story goes that the phenomenon was so popular that the Prussian army even tried to use hawks and falcons against the pigeons but to no avail.

Siege of Paris 1870–1871, pigeon post medal by the artist Charles Degeorge/Wikimedia commons

How the Pigeon Post Worked

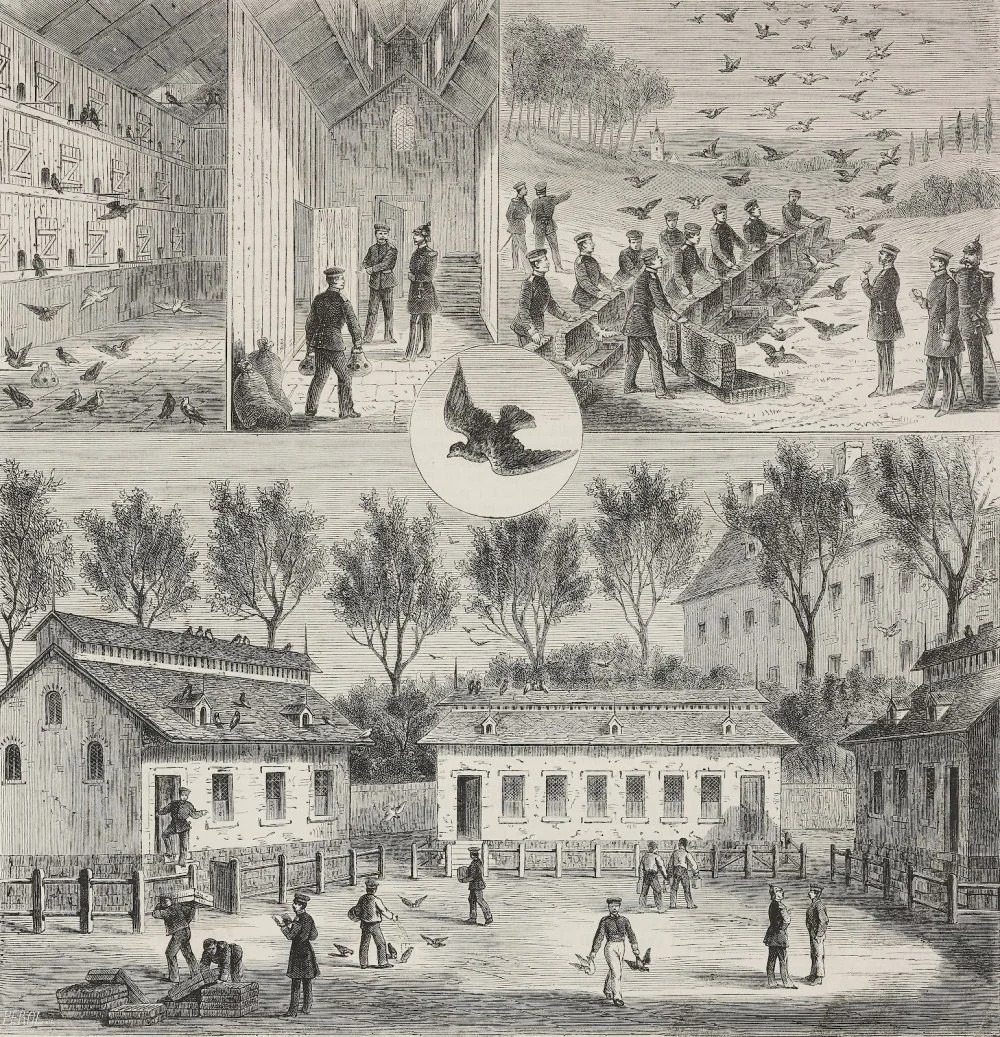

There are many sources from the nineteenth century that shed light on how the pigeon post worked. The size and weight of the message the bird could carry was limited by the physical capabilities of the pigeon. We know that letters were written on a special thin paper and then placed in a capsule or pouch that was attached to the feathered messenger’s foot. In the second half of the century, with the development of photography, microcopies of printed messages became popular, which were then deciphered with the help of a projector.

A mail office using carrier pigeons in Germany, engraving, 1874/Getty Images

The logical result of this union between man and bird was a monument dedicated to the pigeons designed by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, the artist behind the famous Statue of Liberty, and unveiled in 1905 on the Place des Ternes in Paris. However, it was destroyed and melted down during the Second World War and did not survive.

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi’s “Monument des Aéronautes” once stood proudly in the Porte des Ternes, Paris Chronicle/Alamy

Shortly before this monument was erected, the first regular civilian ‘pigeongram’ service of the modern era was established. This was known as the Great Barrier Pigeongram Agency, which operated between Auckland and Great Barrier Island in New Zealand at the very end of the nineteenth century. The first airmail stamps in the world were issued for this service, featuring the very birds we discuss in this article.

In 1895, a postal pigeon once covered a distance of 3,000 kilometers from the United States to Europe.

It wasn’t long before the services of these feathered mail carriers were being used in much of Europe and the United States. Experiments at the turn of the century showed that four out of five trained birds could fly almost 1,000 kilometers and return successfully to their nest or coop. In 1895, there was even a recorded case of one of the pigeons from an experiment covering a distance of more than 3,000 kilometers from the American coast and reaching the European continent unharmed. Interestingly, its mate was left in the dovecote as a kind of guarantee of the bird’s return. It was believed that a pigeon would remain faithful to its mate for the rest of its life, while a single bird could ‘start a family’ away from home.

Of Spy and Heroic Pigeons

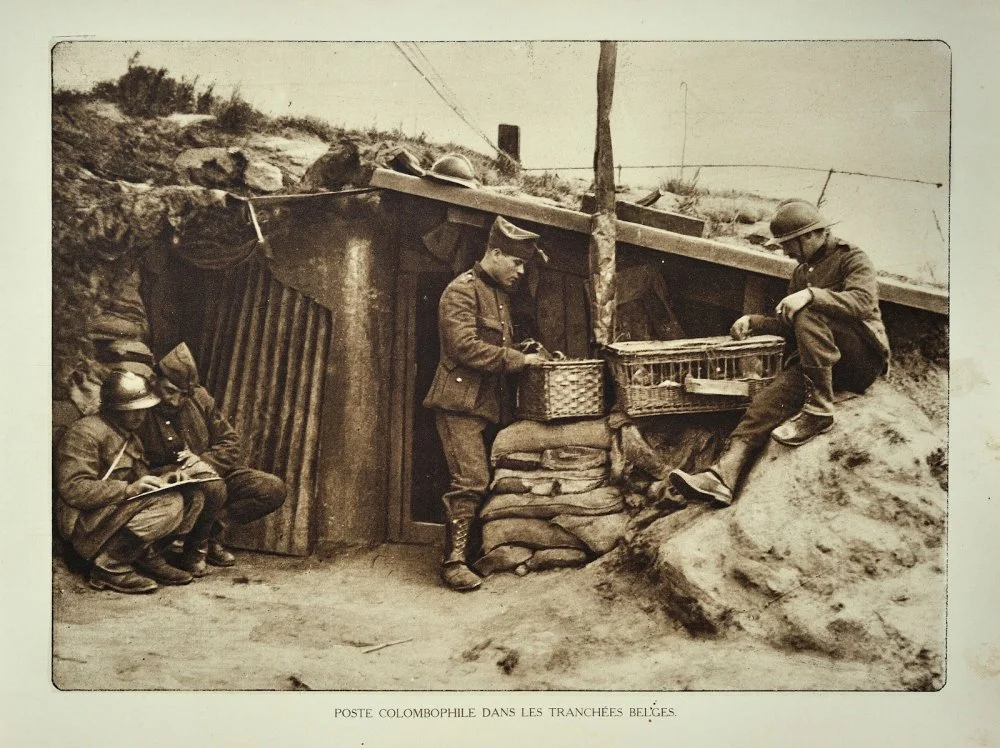

Unsurprisingly, tens of thousands of these useful birds were soon ‘recruited’ to participate in one of the bloodiest military conflicts in the history of the planet, the First World War. In those years, pigeons were used not only to carry military messages—it is said that bird spies worked in the German army for a long time. Small cameras were attached to their bellies, which made it possible to work out enemy positions. Despite their low efficiency, pigeons were used in this capacity until the advent of more predictable and reliable spy planes.

WW1 Belgian soldiers in trench fitting messages on carrier pigeons in West Flanders during the First World War One, Belgium/Alamy

It was also the First World War that brought us the first feathered heroes, and their exploits became very well-known. Perhaps the most famous of these avians was the French messenger bird, Cher Ami, who helped the command find and rescue an entire lost battalion by delivering twelve crucial messages—the bird even received a medal for these missions. After that, the tradition of awarding military decorations to animals became widespread. During the Second World War, the PDSA Dickin Medal was specially established, which became Britain’s highest military award for animals and has been awarded to various animals, including some homing pigeons, over the years.

Against the backdrop of the centuries-long journey of these feathered human helpers who deserved recognition, their rapid devaluation and downgrading to the level of an urban pest, especially in the second half of the last century, seems particularly unfair. As early as the 1960s, the term ‘rat with wings’ was popularized in the English-language press. International popular culture followed suit, and for a long time, a stereotypical and undoubtedly negative image of the pigeon was maintained. The use of birds in drug trafficking did nothing to help this unpleasant image either.

In 1870, pigeons were the only link between Paris, besieged by the Prussian army, and the outside world, and in the twenty-first century, feeding pigeons in the French capital is punishable by a fine of several hundred euros.

The "Pigeon Car" of the French army in the First World War (autumn 1916)/Wikimedia commons