This article was published with the support of ForteBank Kazakhstan

The story of Abylkhan Kasteev’s life has two directions that don’t really align well with one another. The first fits the generally accepted romantic image of the ‘artist’s path’: the little shepherd boy drawing on stones, the labourer, the art school student taking part in competitions and exhibitions, the Kazakh artist whose work is usually mentioned first when talking about Kazakhstan’s art history. The second one is of a government official, a member of Kazakhstan’s Union of Artists, chairman of the Artists’ Union, of someone awarded the official title of ‘People’s Artist of Kazakhstan’ and a whole array of other state medals and decorations, the deputy to the Supreme Counsel of the Kazakh SSR, after whom streets, the art college, and the main museum of the country were named.

His art is just as multi-layered, with many of his pieces looking as though they were created by different people. A good example is a comparison of The Portrait of Kenesary painted in 1935 and The Portrait of Amangeldy Imanov painted in 1950. Despite having many similar features, both portraits depict national leaders, campaigners for the people’s freedom, are painted using oil painting techniques, and are set with masses of armed people in the background. The difference between them is astonishing—and the reason is not even the fact that the first portrait was painted in the style of naïve art and the second is a classic example of social realism.

It would seem that the reason for this transformation is hidden in the fifteen years dividing these two portraits. Speculation about Kasteev’s art being painted by several different people surfaced and was discussed in professional circles long before the emergence of the modern precolonial revisionism that announced one after another Kazakh artist to be either non-existent, fictional, or an opportunistic personality. On the other hand, all these actions have a reason behind them. The totally shameless exploitation of the name ‘Jambula’ for Soviet propaganda would make any contemporary researcher concerned. Evgeny Dobrenko, an Anglo-American researcher of Stalinist culture and historian of literature and cinematography, provided a tough, maybe even somewhat cruel description, of the phenomenon of Soviet jambuliana: ‘A ninety-year-old Jambul, an old man who clearly had not a clue about what was going on around him, and whose fate miraculously took a turn for the best when the savvy “Ostap Benders” [Ostap Bender is a fictional con man and the central antiheroic protagonist in the novels The Twelve Chairs (1928) and The Little Golden Calf (193)] of Soviet literature turned him into an ideological street organ spewing out eastern odes’.

Kasteev was not an old man—quite the opposite—in those years he was in his prime. He had already moved to Almaty, and pieces such as The Inside View of the Yurta, Going to School, A Portrait of S. Kusykbayev, and Turksib had been painted. The union that suggested creating a branch of the Revolutionary Russia Artists Association in Kazakhstan with the aim of providing ‘artistic service and education of working masses’ was already in existence.

In 1933, the organizational bureau of Kazakhstan’s Artists’ Union was created and had started exhibiting works, and by 1934, it was already demonstrating its achievements in Moscow. Kasteev was an active participant in all of these events and because of his involvement, his art was well documented, which leaves not a shadow of doubt that he is very much a real creative entity and that his legacy is not fictional. He wanted to become a ‘true’ artist and learned from his colleagues in museums and from his own trial and error. Of course, there was a big difference between the virtuoso painter A.A. Rittich, who graduated from the Munich Academy of Art, and the self-taught Kasteev, as was noted by Dombrovskiy in a well-known article titled ‘Abylkhan Kasteev—The First Kazakh Painter’. The same author notes the artist’s hard-working nature, an accurate observation indeed. For example, a Shevchenko Gallery catalogue (Kasteev’s museum predecessor), published in 1971, lists 187 stored units. This is not including the National Archive and the collections of the State History Museum.

Looking at Kasteev’s work in chronological order, one can see how step by step he learns to paint ‘properly’, learning the laws of geometric and colouristic composition, the principles of aerial perspective, and realistic modelling. However, apart from the ‘correct’ technique, the propagated style of social realism also required one to have correct thoughts.

The vividness, resemblance and illusionism of his art make his paintings, such as Kuyuk Sheep Farm (1960), Newly Ploughed Fields in the Mountains (1956), and Chaban A. Akhmetzhanov (1966), look very convincing. ‘It is almost unavoidable to suppose that the paintings of Kazakh artists, especially those painted by Kasteev, are not just a social realism embodiment of the communist dream but are indeed the Soviet-Kazakh realization of their understanding of the long nomad history inside such alien environment of painting,’ writes A. Abykaeva-Tiesenhausen, the Anglo-Kazakh researcher of social realism. In her reasoning, educating the ‘Soviet Kazakh’ by the means of visual art is often mentioned.

However, the ‘nurturing’ and ‘creation’ of the new human was not left to art and culture only. The Soviet government often used more radical methods. ‘I insist that the famine of 1930–33 was a direct consequence of Moscow’s determined efforts to turn Turkic-speaking Muslim nomads, known as “Kazakhs”, together with a specific land, Soviet Kazakhstan, into a contemporary Soviet nation. I have come to the conclusion that [the] Kazakh famine was the cruel measure that aided the creation of Soviet Kazakhstan as a stable territory with clear-cut borders and an integral part of the Soviet economic system, and to forge the new Kazakh national identity.’ This is how Sarah Cameron, a professor at the University of Maryland and expert on central Asian society and culture, characterizes the background of the times in which the Artists’ Union of Kazakhstan was created.

On the practical level, famine in Kazakhstan and in Ukraine, as well as in Russia, was one of the consequences of collective farms (or kolkhoz), and it became the goal of Soviet art to manifest a large union-wide project to create an illusion of the happy and abundant lives of the people forced into these collective farms. Along with S. Gerasimov and A. Plastov, both of whom created paintings titled Kolkhoz Celebrations, Kosteev painted Kolkhoz Toi (toi meaning ‘celebrations’ in Kazakh). Remarkably, all three paintings were painted in the same year, 1937, a number that ‘always make one shudder’. It was likely the request or a multiple purchase order of the party and government that made the Artists’ Union of the USSR an offer that they simply could not refuse.

A. Kasteev. Kolkhozny toy. 1937/The State Museum of Arts of the Republic of Kazakhstan named after A. Kasteev.

Naïve art, the genre of Kosteev’s early work, did not fit this task at all, even though it was awarded the status of being an officially recognized artistic movement that was part of modernism and affiliated with names such as A. Rousseau and Pirosmani, and later in the 1920s with I. Generalich, M. Larionov, and N. Goncharova. ‘The painters of many modernist movements … distract the viewer from the burning problems of the present. Their art takes one away from life and its contradictions and not only does it signify the freedom of creativity but in the end it also serves the vested interests of the ruling classes.’ This quote demonstrates how Soviet textbooks on the history of art described the ‘departure from realism’.

The most poignant challenge of Stalinism was to create an obedient ‘new Soviet person’ and to achieve this, it was important to have the similarity, ‘likeness’ and actuality of the image. From the point of view of the theory of social realism, naïve art was not quite convincing enough—it was like a fairy tale, and did not reflect the ‘reality of life’ but instead distorted it. The goal of Soviet art, however, was to do the exact opposite and to turn the fairy tale into reality. Plastov and Gerasimov completed the task set to them brilliantly. Kosteev’s work, on the other hand, was done with such diligence and such attention to the golden rule of composition, seen in the ideal symmetry of the groups of people he painted, in the division of the canvas into three clear-cut perspectives, and in the correct aerial perspective getting more and more hazy in the distance that along with a very strong feeling of the naïve, the contemporary viewer cannot help but wonder about the almost ironic view of the painter. Self-taught Kasteev, albeit subconsciously or quite possibly automatically, somewhat resisted the social realist. To verify these suspicions, one only needs to take another look at Turksib, where the little train is built from what are almost children’s wooden blocks, or at the completely cartoon-like Setting up the Red Army in Kazakhstan (1948).

Landscapes were the ultimate escape for Kasteev and were interpreted by many researchers as his expression of love for his native land. In painting landscapes, he achieved great success not only in mastering the laws of painting but also, most importantly, in conveying emotion and sincerity. Practically all art experts note the poetic, warm, and peaceful nature of his work. The glorification of the scenery, which was a requirement for a typical Soviet landscape, is more visible in the following paintings: Kolkhoz Houses (1947), Kolkhoz Sary Shoki (1948), and even Virgin Soil (1956).

A. Kasteev. Organisation Of The Red Army In Kazakhstan. 1948 / A. Kasteev State Museum of Art of the Republic of Kazakhstan

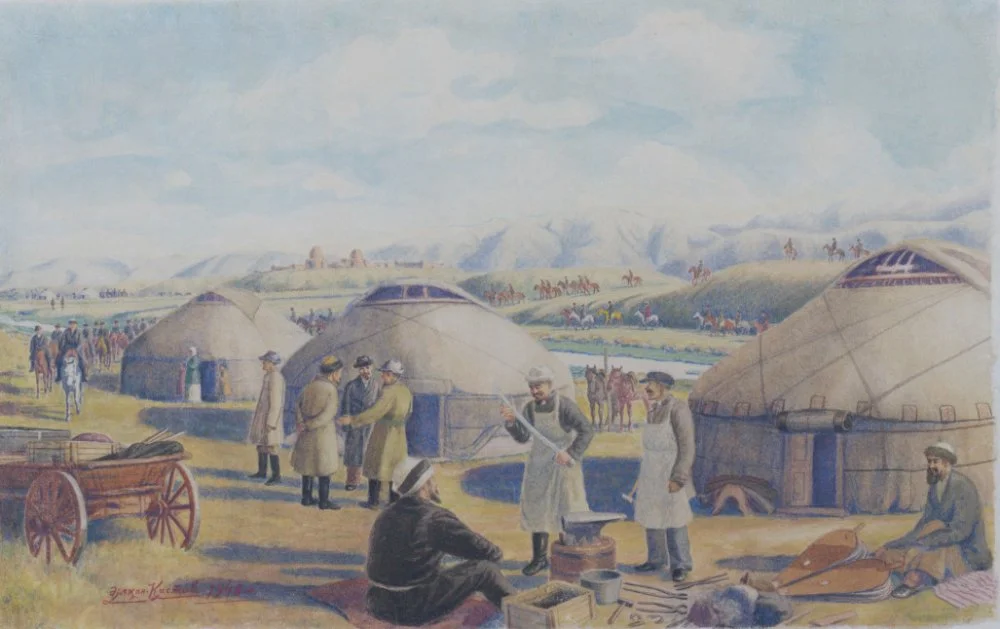

It is quite remarkable that Kasteev did not paint a single portrait of Stalin, which in those days, every artist was doing—even the avant-garde artist Kalmykov. Although, it is true that there are one or perhaps two renditions, they are rather intermediate and can be called portraits only at a push. One work, dating to 1950, is titled A Gift for Stalin. In a rather majestic landscape depicting mountains and rivers, we can see a small aul, where some high-ranking guests have arrived. One of them is wearing a suit; he is possibly a Central Committee (CC) representative. He is busy assessing the resemblance, or lack of it, of a portrait of the leader printed in the newspaper. The second character, sporting a semi-military outfit, most likely from the KGB, is sitting directly opposite the weavers, who are showing him a woven rug with a portrait of the generalissimo on it. He is sitting almost as if in front of a television, and it would appear that his sturdy, well-planted figure has comfortably positioned itself with the aim of staying in place for some time.

As they used to say in publishing houses in those days: it’s best to be over-vigilant rather than not vigilant enough. This one painting has not one but two portraits of Stalin, one of which is in the newspaper, with the second on the rug. Ironically, and in complete contradiction to all instructions, Stalin is not the main character here. And amazingly, unlike The Portrait of Amangeldy Imanov mentioned earlier and painted in the same year, 1950, A Gift for Stalin is quite picturesque, despite being just as detailed. It is most likely the main motive for the artist in this painting is the landscape and the daily life of the aul.

It is possible that the precise manner in which The Portrait of Amangeldy Imanov is painted is due to the artist’s complicated task of trying to convince the audience that the depicted character is real. His challenge was to turn a rebel who led the uprising against the Russian Empire’s intention to recruit Kazakhs to dig trenches in World War I in 1916 into a red commander. The meticulous elusiveness with which the portrait is painted plays the role of documented proof that it is ‘life-like’. And we can go back to the original argument and compare this painting to the vibrant and decorative portrait of Kenesary, who looks like a fairy tale character despite being a completely authentic historical figure. Both of them led movements against the Russian Empire—Kenesary from 1837 to 1847 and Amangeldy in 1916—which enabled the artists to easily tie the latter to the events of the October Revolution of 1917. Social realism film, music, and literature were also meant to become the ‘documented’ proof, and all of those did materialize. The Portrait of Kenesary, however, was stored in the vaults of the museum named after Abylkhan Kasteev up until the 2000s.

References

1. Abykayeva-Tiesenhausen, Aliya. Central Asia in Art. From Soviet Orientalism to the New Republics. London & New York: I. B. Tauris, 2016.

2. Добренко, Евгений. «Джамбул. Идеологические арабески». В кн. Джамбул Джабаев приключения казахского акына в советской стране. Москва: НЛО, 2013.

3. История зарубежного искусства. Москва: Изобразительное искусство, 1983.

4. Камерон, Сара. Голодная степь. Голод, насилие и создание Советского Казахстана. Алматы: СОЗ, 2023.

5. Союз художников Республики Казахстан. 1933-1991. Алматы: Интерпринт, 2009.