Although Shoqan Walikhanov’s life was short, it was filled with bold expeditions, groundbreaking research, and insights that astonished not only the intellectual elite of the Russian Empire but scholars across the world. And yet, despite his fame, many aspects of his story remain shrouded in mystery, especially the final years of his life, which were marked by despair and disappointment, and he developed a profound awareness of the nature of tsarist colonial policy. Even the circumstances of his early death continue to fuel debate. Could a man who amazed his famous contemporaries with his knowledge really have become an instrument of the empire? What darkened his heart upon returning to his homeland?

In his article for Qalam, the prominent journalist and researcher Darkhan Abdik reveals little-known aspects of the figure whose life shaped the intellectual horizon of an entire people for decades to come.

The Heir to the Steppe Aristocracy

In the nineteenth century, as the Russian Empire expanded, it abolished khanate power in the Kazakh steppe and replaced it with the institution of senior sultans. Formal control over the three jüzesi

Shoqan, however, was not merely one of the Töre. He descended from the eldest son of Ablai Khan—Uali, the last khan of the Middle Jüz—and Ablai himself is remembered as one of the most vivid and heroic figures in Kazakh history. His name became legendary, and warriors would shout it as a battle cry before going into combat. And so, even after the abolition of the institution of the khanate, according to Kazakh tradition, Ablai’s great-grandson retained the title of ‘khanzada’, or prince and potential heir to the throne. Naturally, his lineage influenced Shoqan’s fate, and we will discuss this in more detail shortly.

Chinggis Valikhanov (second from the left), father of Shokan Valikhanov, 1865 / Central State Archive of Film, Photo and Sound Recordings of the Republic of Kazakhstan

Shoqan’s noble birth was only one part of a far more complex story. One thing is certain: he did not identify as either a Töre or a khanzada. He was a man of civic disposition and inner freedom, and he maintained a rational outlook on the world. Yet, in order to understand how he managed to ascend so rapidly to such intellectual heights, it is essential to understand the realities of the epoch in which he matured—its contradictions, social dynamics, and political context.

In 1825, the Decembrist uprisingi

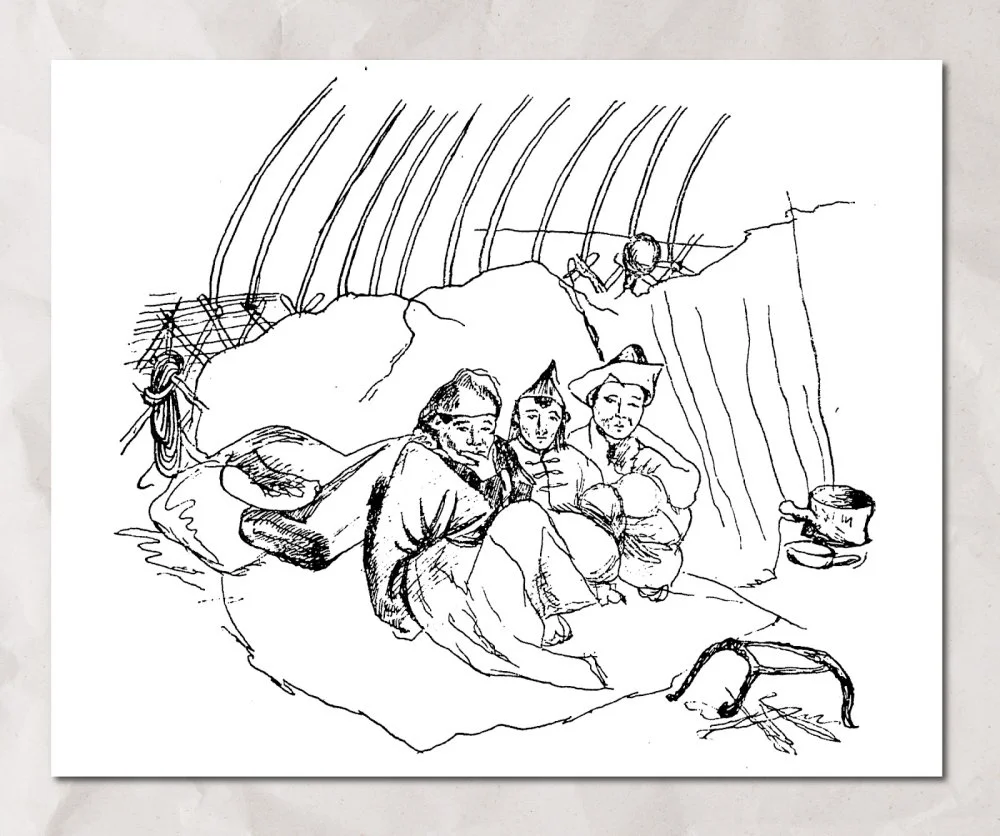

Drawing by Shokan Valikhanov. Portrait of Valikhanov’s brothers, 1855 / Wikimedia Commons

Shoqan’s Childhood

When Shoqan was only twelve years old, he found himself in an environment with a unique intellectual and political dynamic. It was here that his worldview began to take shape, his horizons expanded, and his appetite for knowledge deepened. Yet the spark that drove him did not begin there. His curiosity had taken root much earlier.

Shoqan grew up in an enlightened family that valued modern education. His father Shyngys was an educated and influential man, and one of the first to systematically collect examples of Kazakh oral literature. His grandmother Aiganym was no less remarkable. A woman of immense authority and vision, she oversaw the construction of a wooden estate in the Syrimbet area with support from the Russian administration, and she even established a madrasa nearby, turning her home into a small but influential center of learning and culture. It was there that young Shoqan learned to read and write, mastered the Arabic script, and developed a passion for drawing. According to his friend Grigory Potanini

The Russian town made a strong impression on the boy—he immediately began sketching one of the city’s centers with a pencili

When the young Shoqan first arrived in Omsk, he found the Russian language difficult to learn. Yet, diligence and natural talent quickly took over, and within a few years, he was not only speaking Russian fluently but had also become one of the top students in the cadet corps. Potanin recalled this in an article titled ‘Chokan Chingizovich Valikhanov’:

Chokan developed rapidly and soon surpassed his peers, especially in the fields of political ideas and literature. The corps’ leadership saw in him a future traveler destined to explore Central Asia.

In another article titled ‘Biographical Notes on Chokan Valikhanov’, Potanin writes:

When his teachers began to see him as a future researcher—even a scholar—Chokan was only fourteen or fifteen years old.

Shoqan the Polyglot

Shoqan never completed the cadet corps' final course. According to the rules of the time, representatives of inorodtsyi

Yakov Fedorov. The Syrimbet estate where Valikhanov spent his childhood and youth / Wikimedia Commons

Nevertheless, in 1853, seventeen-year-old Shoqan completed his studies, was promoted to the rank of cornet (a cavalry officer), and was assigned to the administration of the Governor-General of Western Siberia. By this time, Shoqan was fluent in Russian and French, and it was very likely that he knew English as well. In the memoirs of N.M. Yadrintsevi

The fact that Shoqan was the first to record a version of the epic Manasi

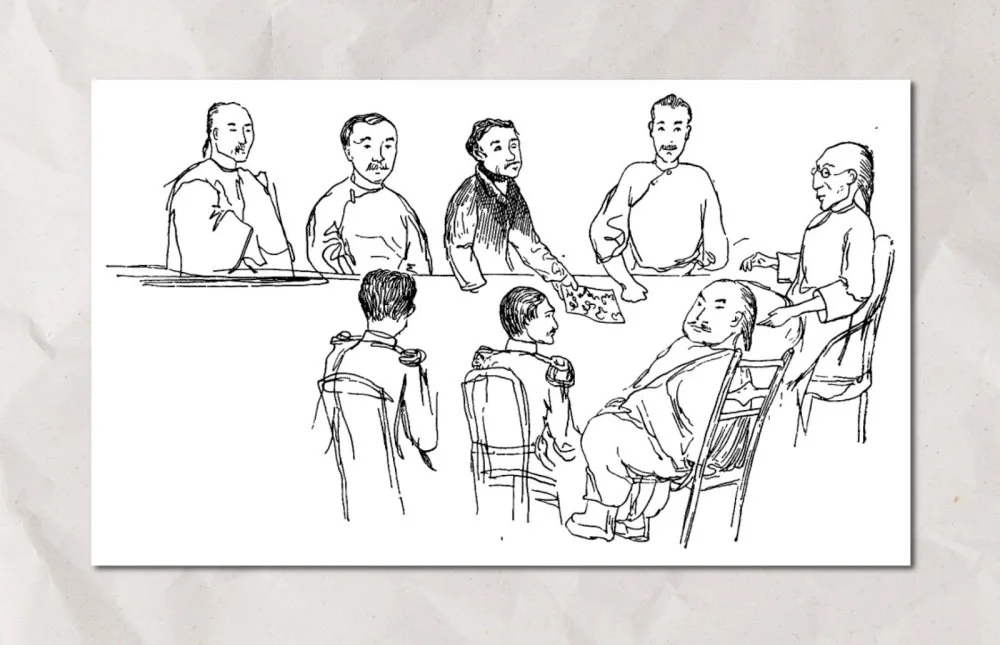

Drawing by Shokan Valikhanov. Reception of a Chinese dignitary in Kulja, 1856 / Wikimedia Commons

Shoqan’s versatile talent and remarkable abilities quickly drew the attention of the imperial administration, and the empire, without hesitation, began to employ the young officer in its own interests. These were times of rapid territorial expansion, when colonial ambitions were reaching their peak. Expeditions to the East included not only military personnel but also scientists and researchers, along with ongoing intelligence work in regions that were potentially destined to come under Russian control.

Yet Shoqan himself, even while carrying out administrative assignments, always prioritized scientific work. It is apparent that he recorded the epic Manas not at the Governor-General's behest but because of his own intellectual passion and ethnographic curiosity. Moreover, he did not merely preserve the text—he conducted a serious literary and textual analysis, presented the epic to the European scholarly community, and dubbed it ‘the Iliad of the steppe’. Throughout this demanding process, his unique approach is evident: a genuine love and remarkable empathy for all of the Turkic peoples without exception.

The Kazakh ‘Indiana Jones’

The Kashgar expedition is perhaps the moment in Shoqan’s life where legend and reality blur so closely that separating them becomes nearly impossible. He was traveling to Kashgar in disguise to produce the first detailed geographical, political, and cultural account of the region for European scholarship. Before reaching the caravan he was to join, Shoqan spent nearly a month traveling alone without weapons or food. By day, he hid in crevices, gullies, and behind rocky outcrops to avoid being seen, and by night, he continued on foot.

When he finally managed to join the caravan, the respite was short-lived as he had to fight off bandits on several occasions. But the real ordeal awaited him in Kashgar. There, posing as a Sart merchant named Alimbay, who had supposedly left the city as a child, he ‘reunited’ with people he had never met before. Having gained their trust, Shoqan risked his life daily to gather the intelligence that had justified the entire dangerous mission.

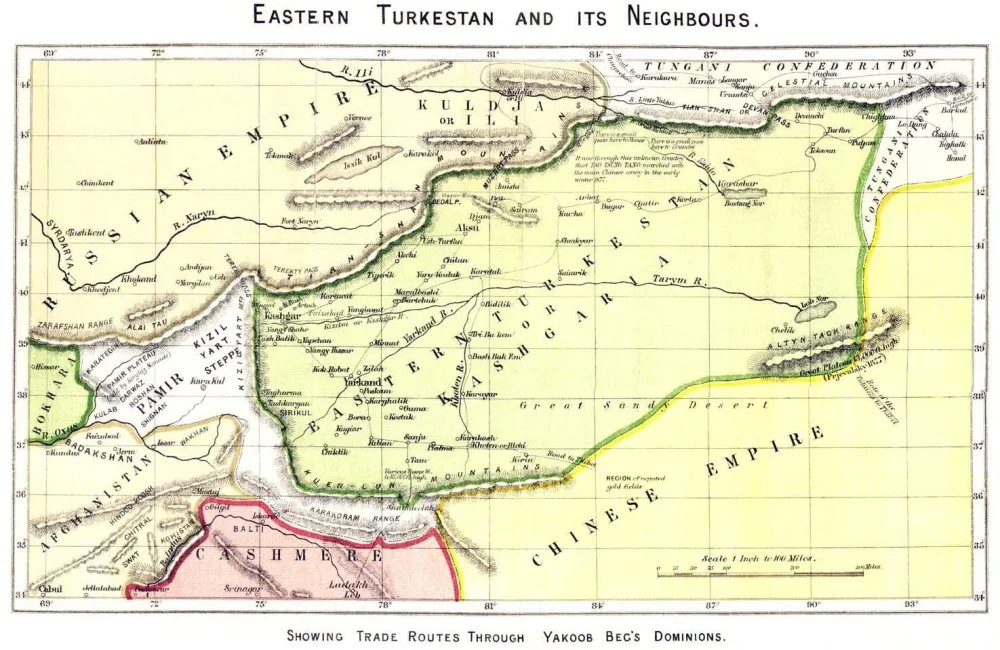

Eastern Turkestan and its neighbors on a British map, 1874 / Wikimedia Commons

In truth, Kashgar, having recently experienced an uprising, made an impression at the time as a truly dark and terrifying place. The surrounding countryside was littered with piles of human skulls, a silent reminder of recent massacres. Just a year earlier, the German researcher Adolf Schlagintweit had been beheaded here, and had Shoqan’s identity been discovered, he would likely have met the same fate. After living in Kashgar for about five months, he felt the tension around him mounting. Disturbing rumors that a Russian spy posing as a Sart merchant had secretly infiltrated Kashgar had spread through the city.

He managed to escape with the caravan literally hours before a pursuing detachment was sent after him. That he returned alive can hardly be called inevitable—it was rather a rare stroke of luck, a true gift of fate. The story of this expedition is so dramatic that it could easily serve as the basis for an adventure film, with a hero in the spirit of Indiana Jones or James Bond. Only this was not the stuff of fiction, but the true story of a twenty-two-year-old Kazakh scholar who lived through challenges of legendary magnitude.

Was Shoqan in Paris?

On 4 May 1860, a meeting was held at the Russian Geographical Society in Saint Petersburg, where Shoqan Walikhanov presented a report on his journey to Kashgar. Nearly the entire scientific elite of the capital was in attendance. Yegor Kovalevsky, the legendary traveler, Orientalist, and diplomat, had read Walikhanov’s work in advance and described it with a single, concise, yet comprehensive word: ‘Genius!’ Shoqan’s courage, the scale of his research, and his scholarly integrity impressed the Russian academic community and also attracted attention across the globe. His reports and monographs were successively translated and published in English, German, and French.

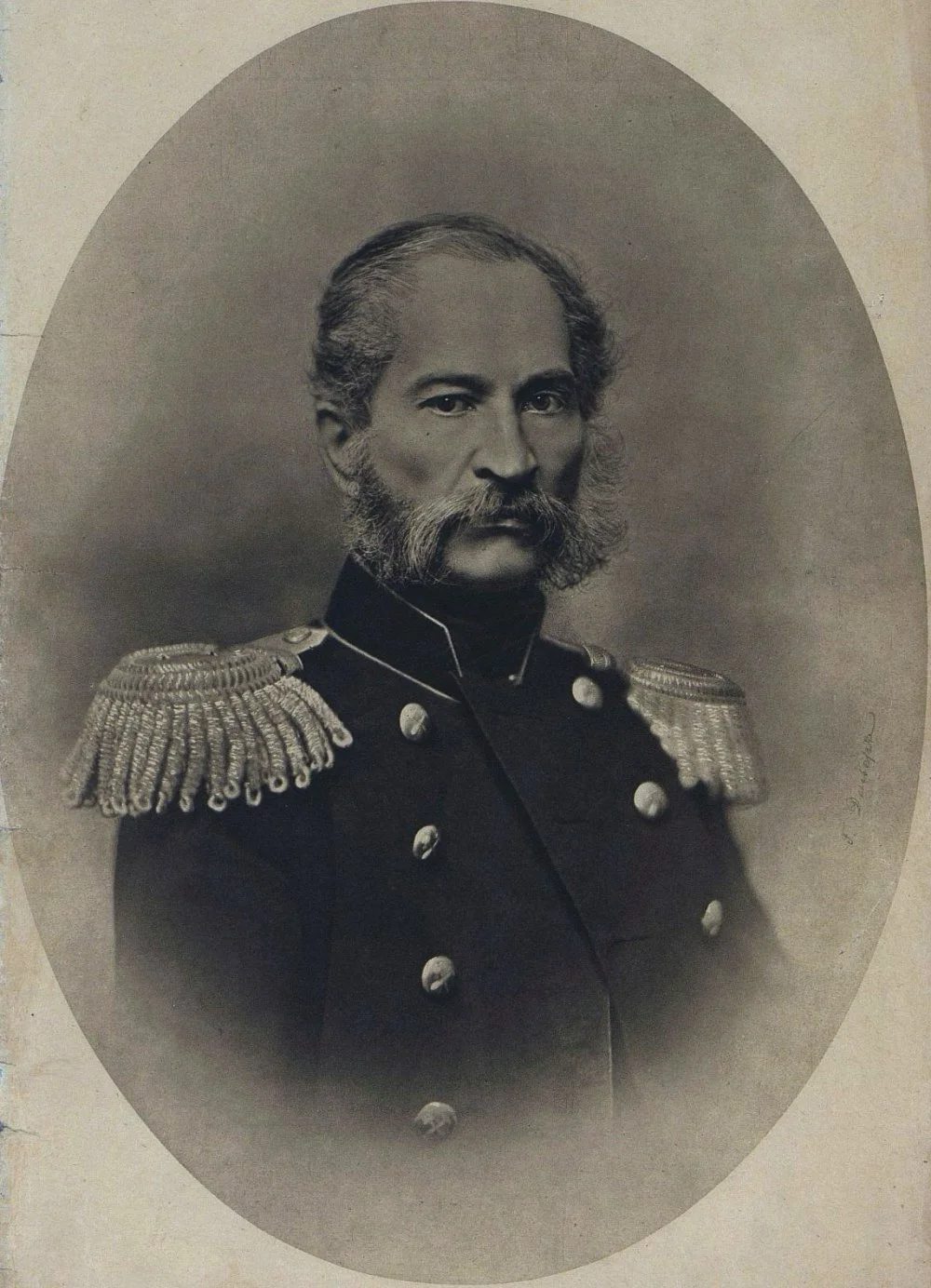

Yegor Kovalevsky, 1860s / Wikimedia Commons

By the emperor's personal order, the young officer was awarded the Order of St. Vladimir, 4th class. Soon after, on the recommendation of the foreign minister Alexander Gorchakov, he was admitted to service in the Asian Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and his military rank was elevated to the rank of staff rotmistri

Indeed, Shoqan, who had received acclaim from the scientific and literary elite in Saint Petersburg, could have visited Paris. While many historians still consider this unproven, two compelling arguments make this version plausible. The first is his own letter to his father dated 4 November 1860, in which he explicitly states that he borrowed money because he intended to travel to Paris and asks that funds be sent as soon as possible. The second argument comes from the memoirs of the Russian diplomat Baron Alexander Wrangel:

Walikhanov made an impression as an exceptionally polite, intelligent, and educated man. I liked him immediately. Dostoevsky was also pleased to meet him. Later, I met him both in Petersburg and in Parisi

However, circumstances would soon change dramatically, and Walikhanov’s fate would take a sharp, unexpected turn.

Return, Alienation from the Empire, and a Wedding Without Ceremony

In the spring of 1861, Shoqan returned to his homeland, heading not to Omsk but directly to his native auli

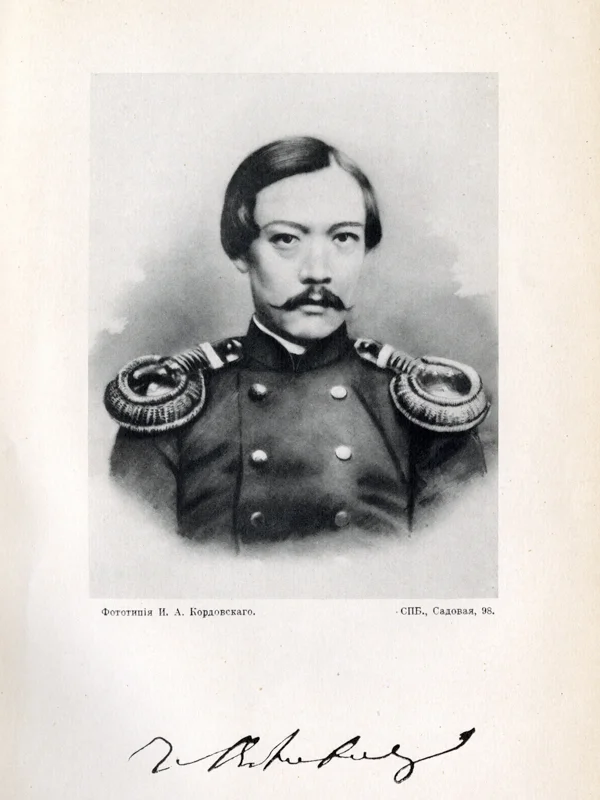

Shokan Valikhanov, 1860 / Wikimedia Commons

In 1863, the Russian administration approached Walikhanov to request his proposals regarding judicial reform in the Kazakh steppe. It was then that Shoqan prepared his famous work, ‘A Note on Judicial Reform’. This was not merely an analytical document but effectively a political manifesto: an open and well-argued critique of the colonial system.

In his comments, he insisted on the necessity of political reforms and directly accused the empire’s administrative and judicial apparatus of corruption and bias. For example, Walikhanov noted a telling fact: justice was sought not only by Kazakhs but also by Russian settlers, who often preferred to turn not to the imperial court but to the traditional court of biys (judges), because, in their view, justice prevailed there more often. Developing his political thought, he wrote:

For any people to develop, they must possess independence, the ability to protect themselves, the capacity for self-rule, and their own system of justice.

He then moved on to a direct critique of imperial governance practices:

The greatest evil in the administration of the Orenburg Steppe lies, without a doubt, in the fact that officials are appointed not as a result of popular choice, but at the discretion of the border authoritiesi

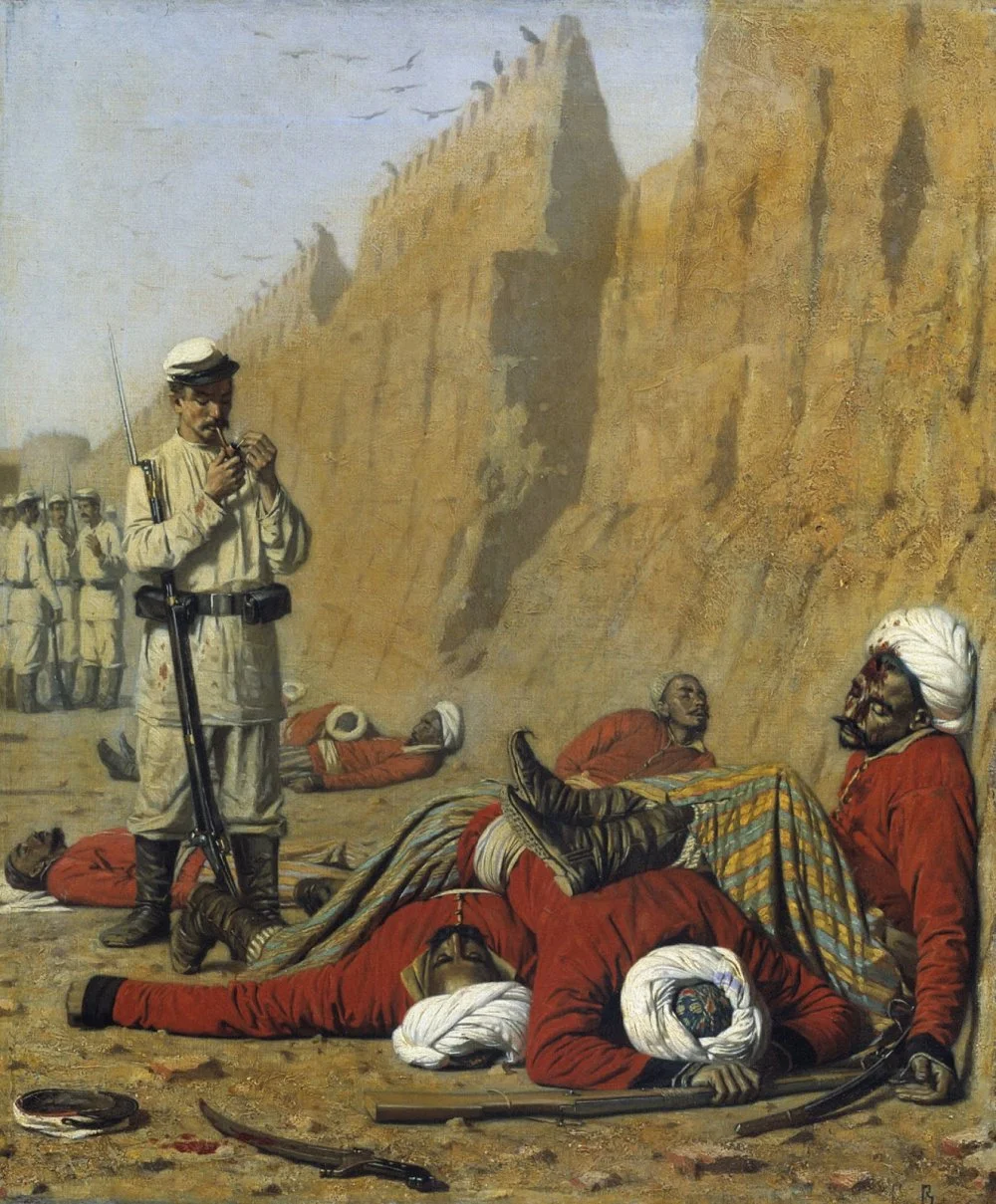

In March 1864, Walikhanov joined the detachment of General Mikhail Chernyaevi

Vasily Vereshchagin. The Apotheosis of War, 1871 / The State Tretyakov Gallery / Wikimedia Commons

He did not, however, return home. Instead, he went to the aul of senior sultan Tezek-Töre, located on the Kazakh-Chinese border. There, he married the sultan’s sister without traditional ceremonies, without matchmaking, without a toy—none of the customs that normally accompany a Kazakh wedding. The marriage of the ‘Kazakh prince’ was so quiet and unobtrusive that it could scarcely be called a wedding. It was, instead, more a modest event, quieter and more unremarkable than even what people without noble lineage could afford. In April 1865, ten months after the bloody events at Aulie Ata, Shoqan Walikhanov passed away.

Questions Without Answers

When you try to make sense of Shoqan Walikhanov’s short but brilliant life and his rich, profound, and meaningful creative path, you inevitably face questions that have no simple or straightforward answers. Why, at the height of a promising career in Saint Petersburg, did he suddenly decide to leave everything behind? Why did he resign from a prestigious position in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs? Why abandon scientific research and return to his homeland?

Shokan Valikhanov and Fyodor Dostoevsky in Semipalatinsk, 1859 / Wikimedia Commons

Why did he decide to run for the position of senior sultan? Shoqan, the son of a senior sultan and an officer in the Russian army, surely understood that, under the colonial system, this position was merely symbolic? The senior sultan would be a ‘puppet leader’ who could not compare in influence or authority to even the lowest-ranking imperial official. And most importantly, why, after confidently winning the election, did he, according to the official report, suddenly refuse to perform his duties, citing health reasons?

In 1865, Grigory Potanin and Nikolai Yadrintsev, Shoqan’s close friends, were arrested and convicted under a ‘political article’ for attempting to achieve the separation of Siberia from the Russian Empire, and they were sent to prison. Yet no case was ever brought against Walikhanov, who had left military service without permission and held the rank of staff rotmistr. Against him, no investigation was initiated—not even a formal inquiry.

In a letter to Kolpakovsky dated 14 January 1865, Shoqan Walikhanov requested that several crates of cigars be sent to him, a request that seems at the very least strange for a man ‘suffering from tuberculosis’.

That same year, at a meeting of the Russian Geographical Society, the eminent scholar Pyotr Semyonovi

In the depths of the Kyrgyz steppes, on the border of Russia and China, the gifted Kyrgyz sultan Chokan Valikhanov perished in the prime of his life.

In the Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language, the verb pogibnut, meaning ‘to perish’, is defined as ‘to die a violent, unnatural death’.

Yakov Fedorov. Grave of Shokan Valikhanov / Wikimedia Commons

Why did such a respected scholar choose exactly this word when speaking of Shoqan’s passing? This question inevitably deepens the doubts and makes the mystery surrounding his death even darker. But one thing is certain: Shoqan Walikhanov’s life still holds many unanswered questions, to which we have yet to find clear answers.