R. Decker. One-leaf print on a witch burning in Derenburg. Circa 1555/Wikimedia Commons

When it comes to the Middle Ages, we often picture fires blazing across Europe, where ‘witches’ were supposedly burned en masse. However, this is a simplified view. In reality, it was the heretics—people who strayed from Catholic dogma—who were burned at the stake during this time. True witch trials were rare until the end of the Middle Ages (fifteenth century), and it wasn’t until the onset of the early modern period in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that Europe was swept by a wave of panic and persecution known as ‘witch hysteria’.

The largest number of witch executions took place in the German lands, France, Switzerland, Scotland, and Poland. In contrast, there were far fewer persecutions in Italy, England, and the Scandinavian countries; in fact, in Spain, Ireland, and Russia, witch hunts were very rare. Let’s look at how this hysteria began and who its victims were.

Francisco Goya. Witches' Sabbath. 1797–98/Wikimedia Commons

The Belief in Witchcraft

The human belief in magic has ancient roots—every culture has myths about sorcerers who can both help people and cast curses, and the Middle Ages and the early modern period were no exception. Even though Christianity had become the official religion across Europe, the church was, in essence, one branch of authority. Pagan practices still persisted in society: villagers would jump over fires during festivals, make offerings to various spirits, and, of course, believe in magic, often turning to folk healers who knew special spells and the ‘healing’ properties of plants. This is understandable: the Bible was in Latin, and most peasants, and sometimes even members of the higher classes, couldn’t read. Knowledge of the faith was passed down through the local priest, who was sometimes also illiterate and far from the ideal of Christian morality.

Numerous fortune tellers roamed the cities, predicting fate by watching the flight of birds or tossing stones into the air. Occasionally, more gruesome methods of divination were used, such as reading the entrails of animals or even human bones (which could be purchased from the city executioner).

Witches colluding with a demon (2nd quarter of the 15th century): Cotton MS Tiberius A VII/1, f. 70r/Wikimedia commons

Even educated physicians did not shy away from using magical rituals and alchemy. Many intellectuals between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries dreamed of creating an elixir of immortality or a universal cure for all diseases. And for this, they relied not on scientific methods but on magical practices, on combining various substances and casting spells.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The Alchemist/Wikimedia Commons

Belief in all kinds of wonders, including witches, permeated society. The church, however, denied the existence of witchcraft for a long time. But there was also a political element to this: by reconciling pagan beliefs with the official religion, the church avoided the need for bloody conflict with society. The Inquisitioni

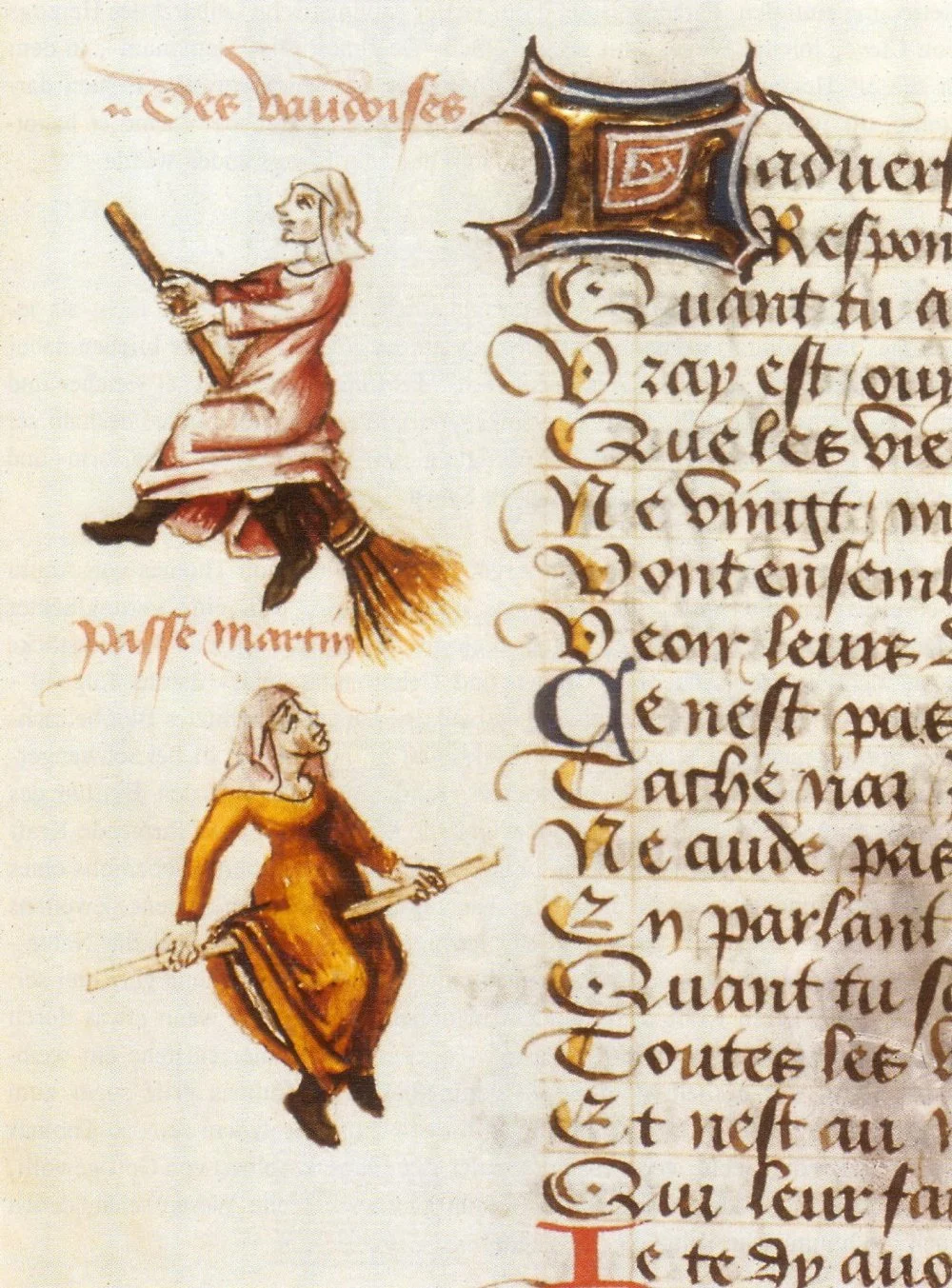

Martin Le France. Illumination depicting the two witches on a broomstick and a stick/Wikimedia Commons

In rare cases, secular courtsi

When Did the First Fires Ignite?

In 1324, an Irish bishopi

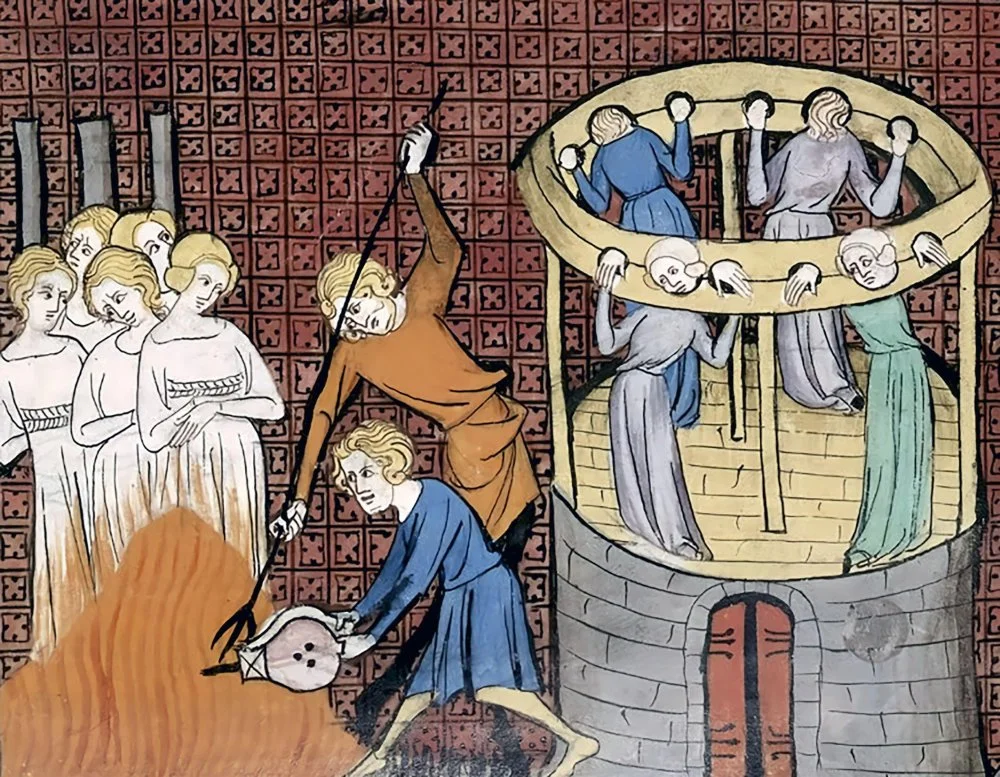

Witch Burning. 14th century illustration/Wikimedia Commons

The spread of witch trials was further fueled by the idea that witches were just like heretics. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Christian Church fought to preserve the purity of faith, and the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries were marked by a fierce campaign against heresy. In 1326, Pope John XXII issued a bulli

The execution of Joan of Arc /Wikimedia Commons

A striking example of this shift was the trial of Joan of Arci

The Hammer of Witches and Mass Persecutions

In the fifteenth century, some inquisitors became professional witch hunters. The most famous among them was the German monk and theologian Heinrich Kramer (1430–1505), who was a true fanatic and may have suffered from mental disorders. He was obsessed with the idea that sects of heretics and witches were conspiring everywhere.

The inquisitor's motto (and that of many of his followers) could be summed up by a quote from the Old Testament: ‘Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live’.i

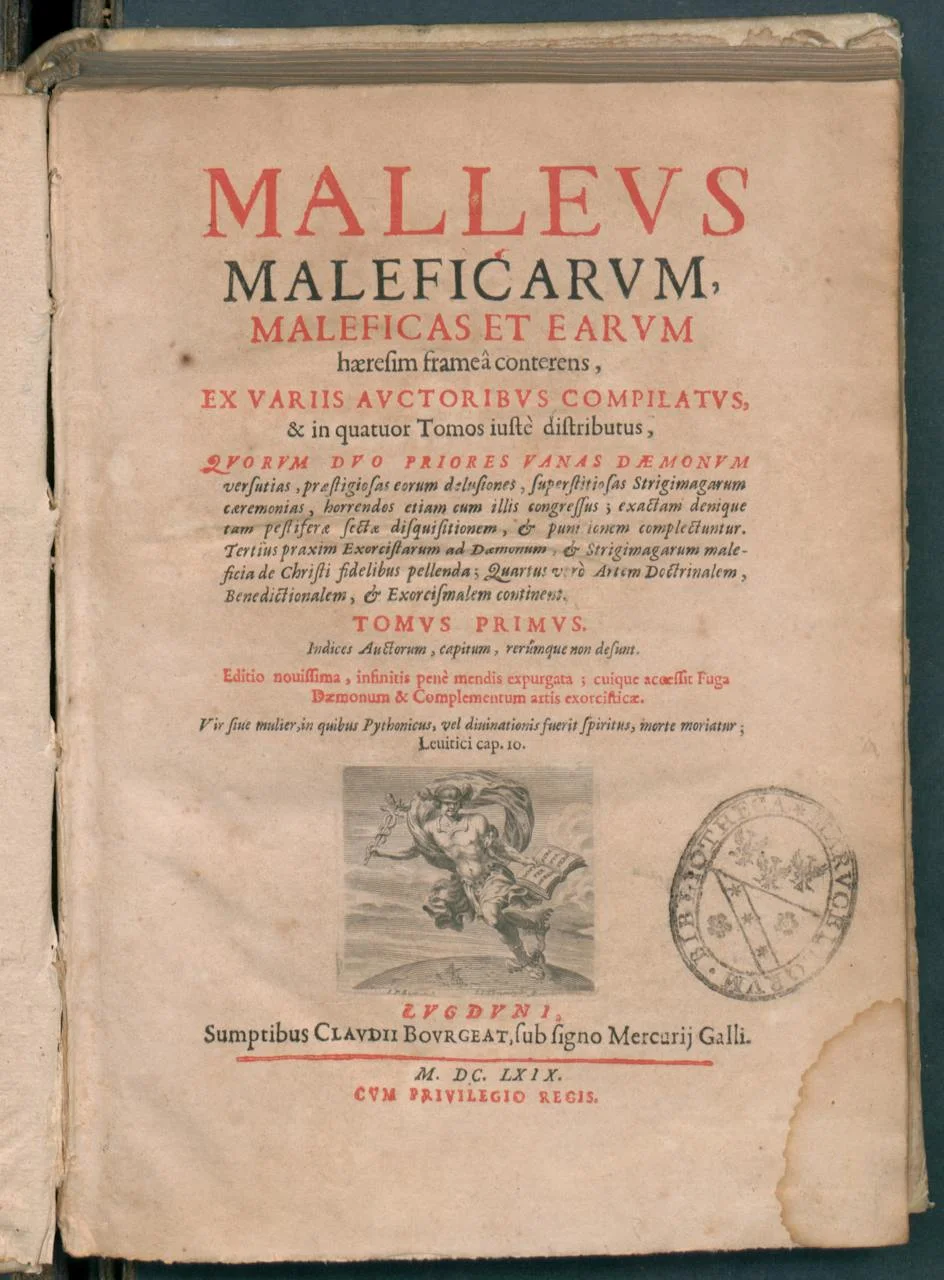

Wishbone. Malleus maleficarum. 1669/Wikimedia Commons

In 1485, Kramer condemned several women to be burned at the stake in the German city of Innsbruck, but the local bishop disagreed with the sentence and was appalled by the brutality of the interrogations. Ultimately, the women were acquitted, and Kramer himself was expelled from the city. Despite this setback, the relentless witch hunter managed to win the favor of the pope and persuaded him to issue a papal bull ordering the search and destruction of witches. Thus began the era of mass executions.

Kramer’s primary ‘achievement’ in the fight against witchcraft was the publication of a treatise in 1490 titled Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches). One section of this work describes all sorts of crimes related to witchcraft. It claims that witches can summon demons to harm people and kill and boil newborn infants in cauldrons. They could cause livestock to die, epidemics, and crop failures, as well as poison wells, seduce people with spells, and commit numerous other horrific acts. Another section provides detailed instructions on how to find, interrogate, and best execute a witch.

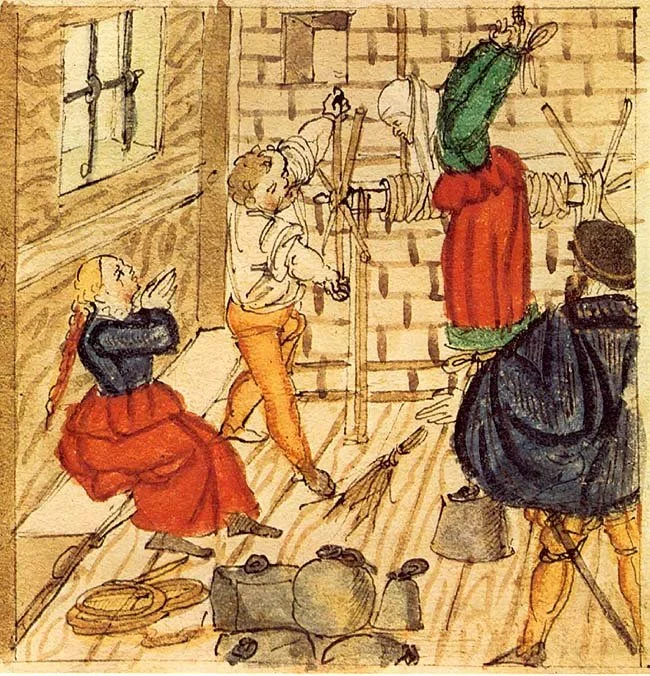

Torture/Wikimedia Commons

Forty-five years before The Hammer of Witches was written, the printing press had been invented, allowing books to spread quickly across the world. Kramer’s work gained immense popularity—printed in large quantities and translated into many European languages. The more priests and judges read The Hammer of Witches and similar works, the greater their fear of black magic grew. Increasing numbers of people were sentenced to burning.

Terrible Centuries

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the early modern period, saw numerous severe trials being conducted all over Europe. In 1517, the Reformation began a massive sociopolitical movement to restructure the church. Its supporters, known as Protestants, criticized the wealth of the Catholic Church and the power of the pope. The Reformation led to unrest, religious wars, and peasant uprisings. Moreover, the Little Ice Age, a global cooling followed by crop failures, famine, and epidemics, began around this time.

Those accused of witchcraft could be forced to testify against other ‘witches’ under torture. The torment compelled them to ‘betray’ even their closest loved ones. Often, children under pressure accused their own parents of witchcraft. In 1601, a heartbreaking story unfolded in Offenburg, Germany: executioners brutally beat ten-year-old Agatha Gwinner, forcing her to accuse her mother of being a witch. On hearing her daughter’s accusations, the mother exclaimed in anguish, ‘Wretched child! Why didn’t I drown you as an infant?’ The girl replied, ‘You should have!’

Interestingly, some particularly impressionable individuals, amid the hysteria, even accused themselves. One such case occurred in Navarre in 1614, involving the Spanish inquisitor Alonso de Salazar. Several women declared they had entered his bedroom at night and tried to harm him using a potion. Salazar merely laughed at them, saying he was in perfect health. These women, however, were fortunate to escape punishment.

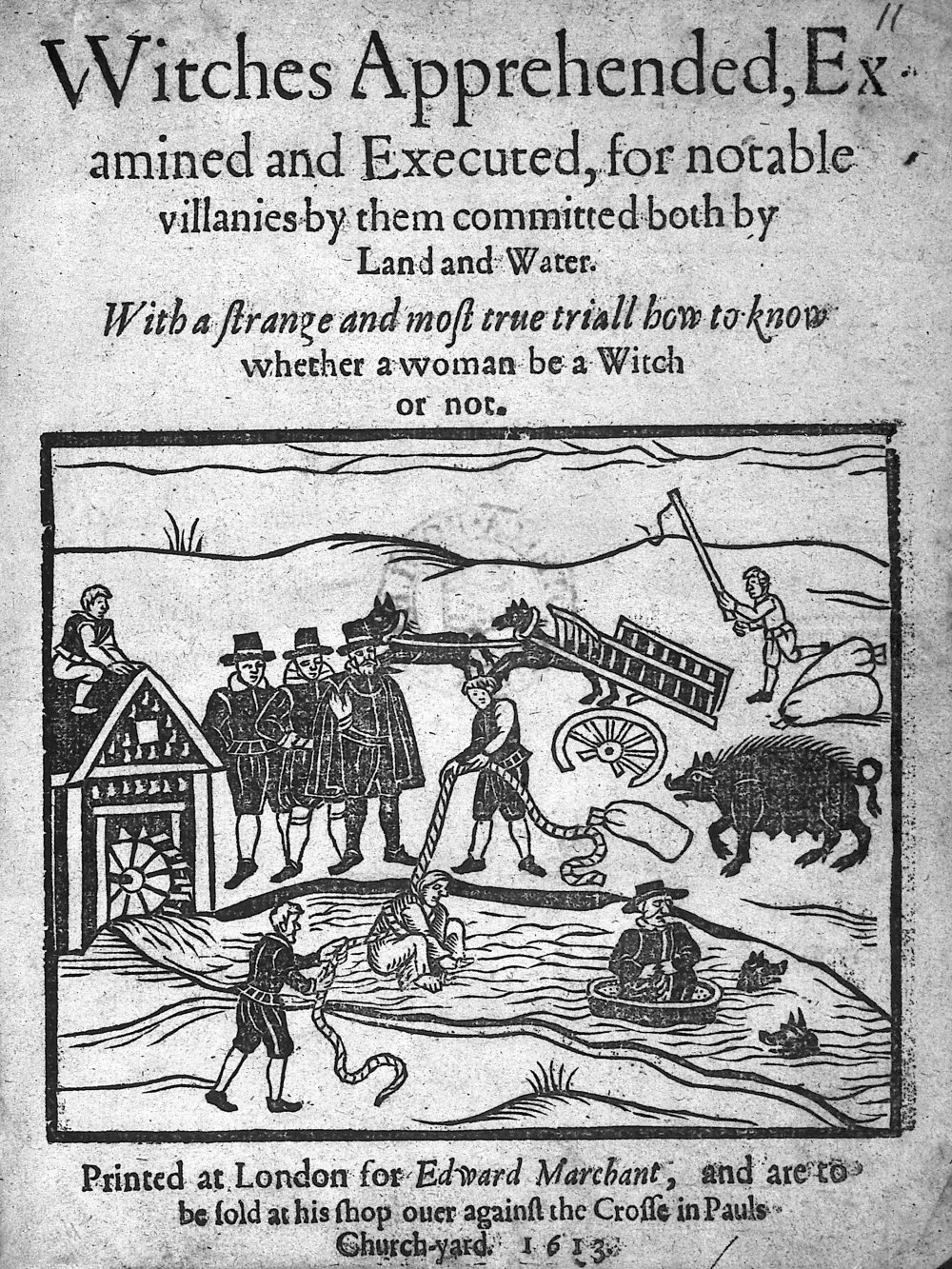

A 1613 English pamphlet showing "Witches apprehended, examined and executed"/Wikimedia Commons

However, more often, the consequence of such behavior was execution. Even the slightest suspicion could lead to accusations of witchcraft. Both the Catholics and Protestants persecuted witches, with fires blazing across Europe until the late seventeenth century, with isolated trials occurring even into the eighteenth century. Modern estimates suggest that between 50,000 and 100,000 people were executed over the entire period of the witch hunts.

How Do You Identify a Witch?

Women were most often the ones accused of witchcraft. Historians have calculated that only 20 per cent of the victims of these persecutions were men. This was due to the profoundly misogynistic (deeply prejudiced attitudes towards women) culture of the Middle Ages, where the popular and prevalent belief was that all women were lustful and prone to sin, and thus to witchcraft. This idea was rooted in the biblical story of Eve, humanity’s foremother, who succumbed to Satan and persuaded Adam to break God's command. In The Hammer of Witches, Kramer even asserted:

‘All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which in women is insatiable.’

Simply being female was thus already a compelling argument for accusation. Especially vulnerable were the single older women, spinsters, widows who refused to remarry, and, as we have talked about earlier, the healers. A common saying held: ‘If you can heal, you can also bewitch.’ Single women were treated with suspicion, and if any misfortune occurred nearby, suspicion immediately fell on them. Red hair was also considered a sign of traitors and apostates from God, and thus hair color could be a valid reason to send someone to the stake.

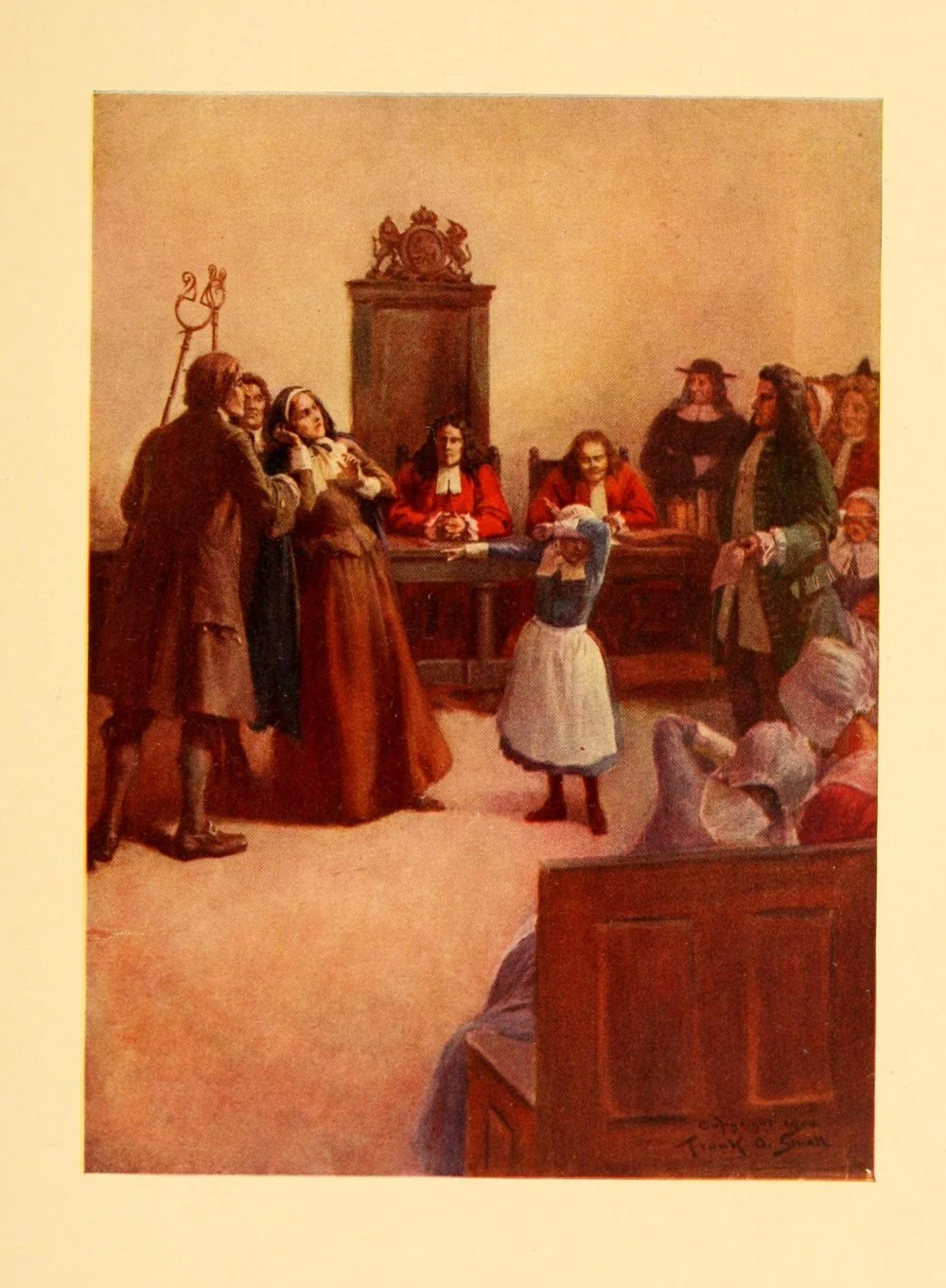

Tompkins Matteson. Examination of a Witch/Wikimedia Commons

Not only appearance but also behavior could also raise suspicions. The French judge and demonologist Jean Bodin, who lived in the late sixteenth century, advised observing how often a woman cried. If she couldn't shed a tear at a funeral or during confession, she was surely a witch. In 1692, in the American town of Salem, a woman named Rachel Clinton was declared a witch simply because she was consistently unfriendly with her neighbors and often in a gloomy mood.

It was also believed that a witch could have a familiar, a demon helper in the form of an animal. Thus, keeping a black chicken, dog, or sheep was suspicious. Cats of any color were considered servants of Satan, and their owners could hardly hope for mercy or acquittal.

In 1618, the English lawyer and witch-hunter Michael Dalton created a special manual stating that witches invariably used the assistance of spirits. Dalton wrote:

These spirits appear now in one form, now in another: sometimes as a man, sometimes as a woman, a bird, horse, hare, rat, toad, etc [...]. The spirit enters the body through the nostrils, ears, mouth, or anus and exits in the same way.

In the case of the English ‘witch’ Ursula Kemp (hanged in 1582), her own son’s testimony was presented as evidence. The boy claimed his mother had a clay pot that housed a white lamb, a gray cat, a black cat, and a black toad—all, of course, ‘demon servants’. Ursula allegedly fed them beer and pastries and sometimes even her own blood. This clay pot (seemingly quite ordinary) was submitted as material evidence in the case.

Frank O. Small. A Salem Witch Trial. 1904/Wikimedia Commons

It was even worse if unusual items were found in the suspect’s home. These could include dried herbs, rabbit foot amulets, bird bones, or sheets with ‘magical drawings’. These were seen as undeniable proof of guilt. Superstitions were widespread, and people often kept charms and talismans, so if there was a will, there was a way for just about anyone to be accused.

Witches were believed to attend sabbaths, devilish gatherings where they danced with demons, ate human flesh, and cast curses. So, taking solitary walks, especially at night, was risky as neighbors might assume the person was headed to a sabbath and report them to the authorities. Witch hunters were also convinced that a witch could become pregnant by the Devil, giving birth to monstrous creatures. For instance, Bodin recounts that in Laon, a woman gave birth to a toad, proving she was a witch.

When a witch was captured, she was carefully inspected as inquisitors believed the Devil left special marks on her body. These could be birthmarks, scars, or even pimples.

«The witch no. 1» lithograph. 29 February 1892/Wikimedia Commons

In England, people believed that if a woman had a wart on her face, a demon might appear in the form of a black chick to suck blood from it. All suspicious marks on the body were pricked with a needle, and if blood failed to flow from any of them, it was considered definitive proof of witchcraft.

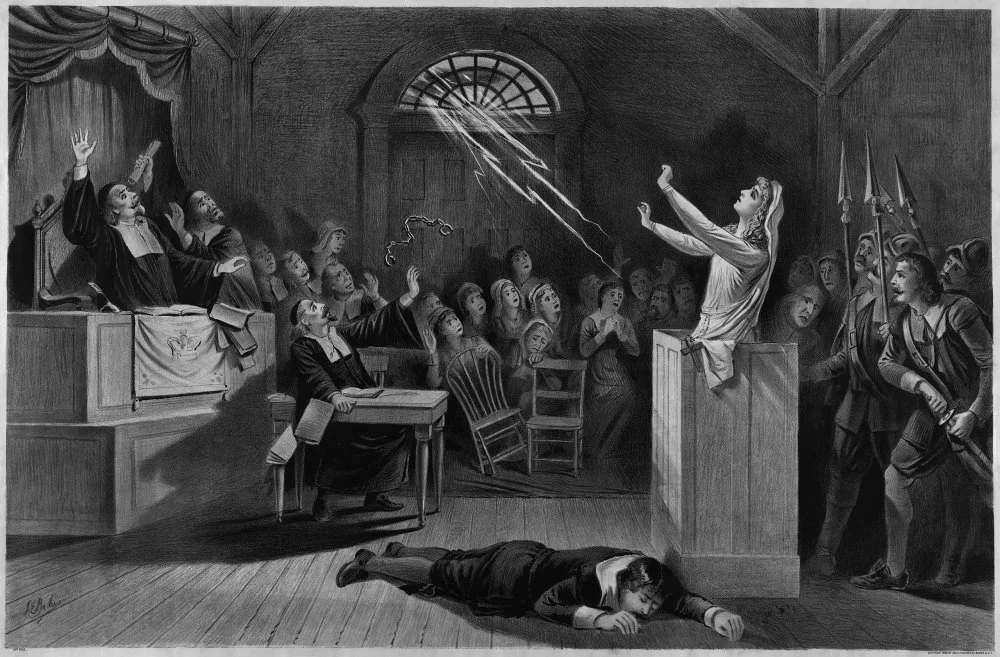

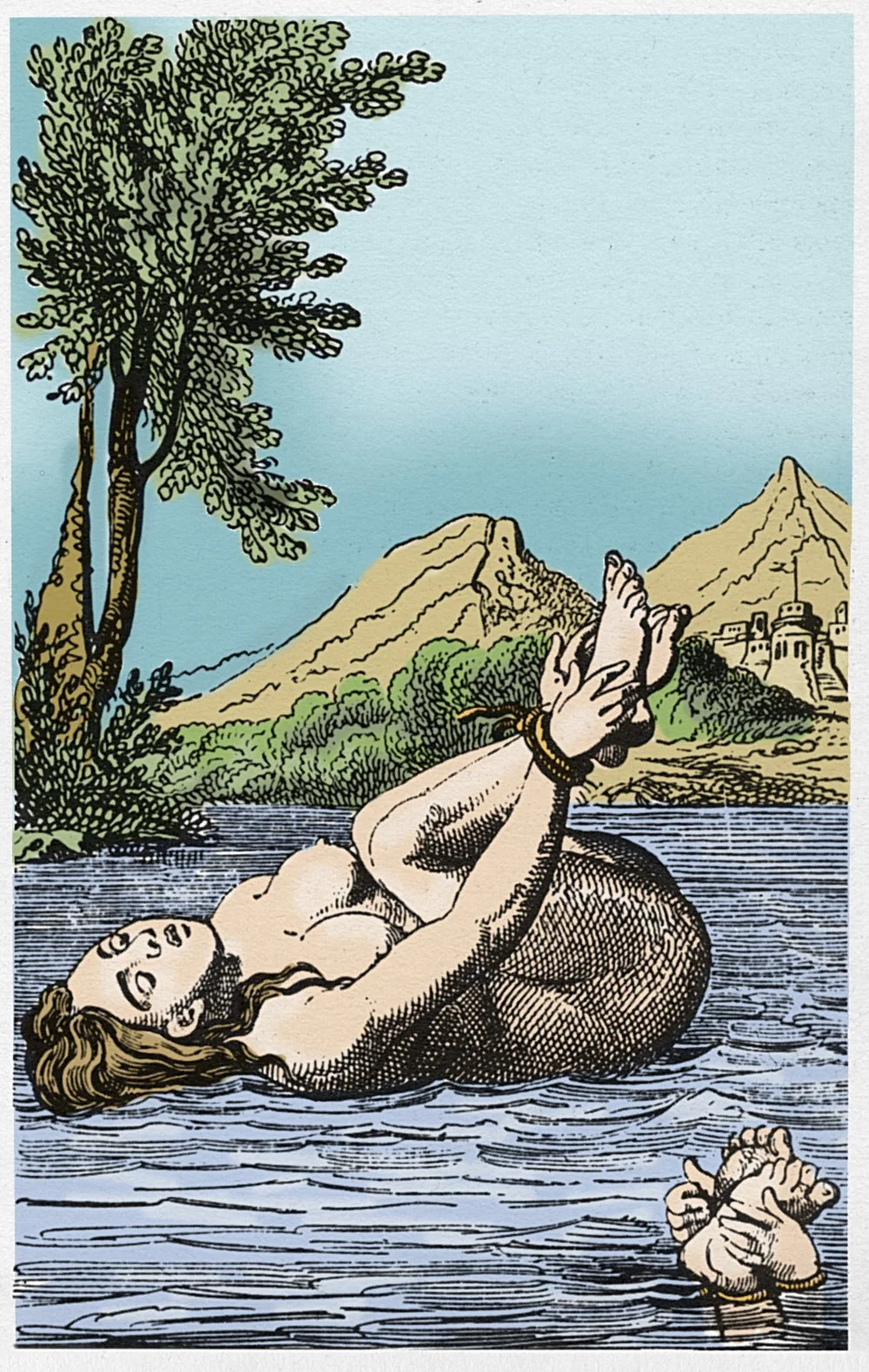

There was another way to test for association with witchcraft: binding the suspect’s hands and feet and throwing them into water. If the person floated, it was believed the Devil was saving his accomplice. In that case, the accused would be pulled from the water, dried off, and burned. If the unfortunate person sank, it was taken as a good sign that they were innocent of witchcraft. No one was concerned that an innocent might drown—if this happened, it was believed God would immediately take their soul to heaven.

Witch Execution. Colored engraving, Germany approx. 1550/Fototeca Gilardi/Getty Images

However, the process did not end after such tests. Investigators would also use various forms of torture to force a confession. Only then was the exhausted victim executed, usually by burning or hanging.

The End of the Witch Hunts

The peak of witch hysteria took place in the seventeenth century. For the European world, this was a time of social upheaval including revolutions, wars affecting the entire continent, and poor harvests. During this period, the fear of witchcraft reached alarming levels; it was not only lonely, poor older women who were sent to the stake—just about anyone could be accused. Increasingly, wealthy individuals were executed, allowing the church to seize their property. Men and women, as well as children, were branded as witches. The horrors of the witch hunts were vividly described by the bishop of Würzburg in 1692, the very end of the seventeenth century:

In the city, there are at least 400 witches of both genders, of high and low status, even priests [...], no fewer than forty students. A few days ago, the dean and the notary were arrested [...]. At least a third of the city is surely guilty. A week ago, a nineteen-year-old girl was burned; she was the most beautiful in the city [...]. I saw how seven-year-old children were executed.

Interestingly, the seventeenth century was also a time of great scientific discoveries coinciding with the final surge of the monstrous witch hunts. The end of witch trials in Europe marked a new stage in the development of culture, science, and the arts—the Age of Enlightenment. An increasing number of intellectuals began writing about the absurdity of accusations of magic. The last person executed for witchcraft in Europe is considered to be Anna Göldi, who was executed in Switzerland in 1782. Although she confessed to witchcraft under torture, she was officially sentenced to death for poisoning.

And yet, even today, there are still legal prohibitions against witchcraft in some corners of the world, and people continue to believe in witches.

Aleister Crowley is an English occultist, poet, artist, writer and mountaineer, known as a black magician and Satanist. 1912/Wikimedia Commons. 1912/Wikimedia Commons