Santa Claus, the jolly old man soaring through the sky in a sleigh pulled by reindeer, is a well-known and well-loved figure across the world, and he has become a staple of global pop culture. But where does this iconic representation of all things Christmas actually live? The immediate answer is often the North Pole or Lapland—in fact, the Finnish town of Rovaniemi boasts an official Santa Claus Village.

Santa Claus sculpture at square in front of the Saint Nicolas church in Demre, Turkey/Wikimedia Commons

However, not everyone agrees with this geographical placement of the beloved holiday symbol. According to the people of Turkey, Santa Claus, known in Slavic culture as Ded Moroz, is one of their own. After all, Saint Nicholas, the historical figure who inspired the cheerful Santa, lived centuries ago in what is now modern-day Turkey. Moreover, Turks have long venerated Saint Nicholas, whom they called Aziz Nikola (or Aya Nikola).

Today, however, he is known in Turkey by his French nickname, Noel Baba, which literally means ‘Father Christmas’ (Noël meaning ‘Christmas’ in French and Baba meaning ‘father’ in Turkish). While children in Istanbul, Ankara, and other major cities look forward to receiving gifts from him, along the Mediterranean coast, he holds a more traditional role. Here, Noel Baba is still revered by fishermen, who pass down menkabe (menkıbe in Turkish)—legends of saints—recounting his tales and miracles.

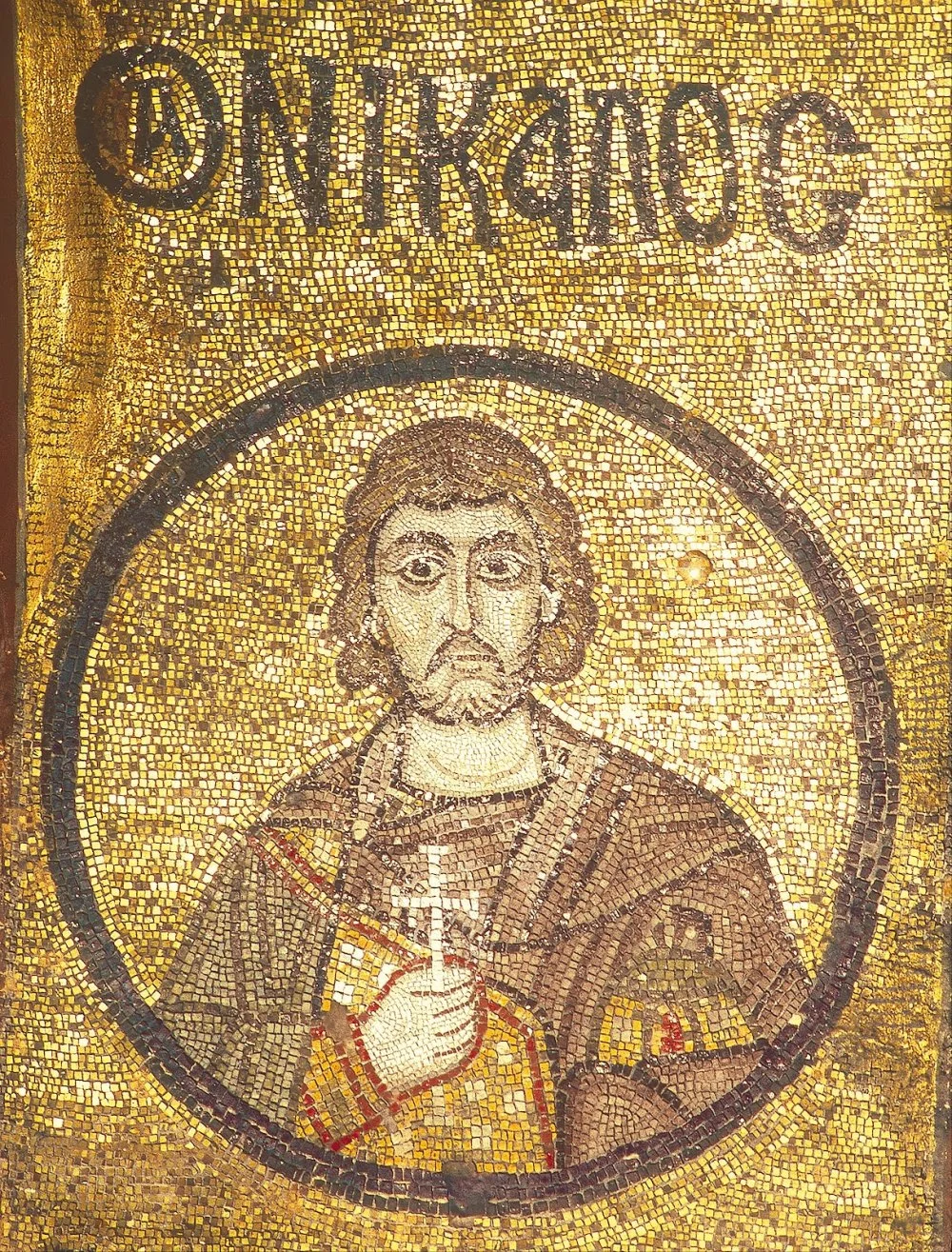

Nicholas, Martyr of Sebaste. Found in the collection of Saint Sophia Cathedral, Kiev/Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

The veneration of saints is an important aspect of Turkish folk Islam. The most common themes in folk tales and fables are stories about righteous figures and saints and the miracles they have wrought. Researchers believe that several factors have influenced the popularity of these stories, including the ideas of Sufism, which is a mystical and less dogmatic interpretation of Islam; the proximity to Balkan and Anatolian peoples who revered dozens, if not hundreds, of saints; and the Turkic ancestor cult. It is no coincidence that in Turkish menkabe legends, saints are invariably referred to as baba (father) and dede (grandfather).

Ambrogio Lorenzetti. St Nicholas Saves Mira from Famine/Art Media/Print Collector/Getty Images

In Turkey, stories about Noel Baba range from how he calmed a storm at sea and miraculously filled grain storages during a year of famine to how he helped end a plague epidemic. Perhaps the most famous story about Saint Nicholas, also known to Turks, is how he threw small bags of gold into the window of a poor man’s house at night so that his daughters could have dowries and get married. It’s worth pausing here to note that ancient writers managed to merge two different Saint Nicholases into one figure. These saints lived in Lycia, in the southwest of modern-day Turkey, nearly two centuries apart—from the third to the fourth and in the sixth centuries.

Myra, St. Nicholas church/Schellhorn/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Today, Lycia, the region where both Saint Nicholases lived, is located near the heart of Turkey’s beach resort area. In the town of Demre, historically known as Myra of Lycia, stands a basilica officially named the Noel Baba Kilisesi (Noel Baba Church). There is also a museum of the same name at the same site, and notably, this church was never converted into a mosque.

The Sarcophagus of Nicholas of Myra/Getty Images

Here, visitors can also see a statue of Saint Nicholas created by Russian sculptor Grigory Pototsky. From the year 2000, it stood in the center of the town, but in 2005, the authorities decided to remove it, likely because it appeared too iconographic and overtly Christian. The new mayor of Demre, Süleyman Topçu, ordered the statue to be moved to the museum and replaced it with a sculpture of Santa Claus resembling the Coca-Cola advertisement—a jolly, plump man in a red coat carrying a sack of gifts.

According to Topçu and some Turkish public figures, this decision had nothing to do with xenophobia or hostility toward Christianity. Instead, the Western Santa was seen as a more globally recognizable image capable of attracting more tourists. However, the new statue failed to win over Turkey’s Minister of Culture and Tourism, Ertuğrul Günay. He found the depiction of Santa in a fur coat with reindeer rather odd against the backdrop of the sunny Mediterranean coast.

Myra, St. Nicholas church, statue of St. Nicholas/Raimund Franken/ullstein bild via Getty Images

And so, in 2008, Santa was removed and replaced by a third statue—this time intended to represent the ‘authentic Lycian saint’. The idea was to make Noel Baba resemble a local resident—and it worked. His face, headgear, and clothing leave no doubt that this is an inhabitant of the Turkish Mediterranean region. Noel Baba is depicted holding a little girl's hand, with a boy sitting on his shoulder—the happy father of a little Turkish family!

Myra, St. Nicholas church, statue of St. Nicholas/Photo by Raimund Franken/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Of course, the secular New Year and its celebration are relatively new phenomena in Turkey. The country only adopted the Gregorian calendari

Moreover, the growing influence of conservative Islam in Turkish politics over the past few decades has not always embraced foreign festivities, especially the veneration of Christian saints. Despite this, Noel Baba has not lost his standing. Before setting out to sea, fishermen along Turkey's southern coast often toss small wooden figures of him into the water for good luck, and children believe that on New Year's Eve, this kind wizard fulfills their wishes.

St Nicholas. 19th century/Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images

Meanwhile, in 2005, the first translation of Letters from Father Christmas by J.R.R. Tolkien, published as Letters from Noel Baba, was published in Turkey. The book was translated by Leyla Roksan Çağlar, who was only sixteen years old at the time. In her own words, she wanted to make the text ‘as Turkish as possible’i

Additionally, the Christmas treats mentioned in the text, such as figgy pudding, were replaced with more familiar Turkish sweets, like muhallebii

The statue of Saint Nicholas located in the centre square of Demre, formerly Roman Myra, on the Mediterranean coast of Turkey/Alamy