In normal parlance today, the name of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is often shortened to and used as ‘Lithuania’. However, it is rarely expanded to its original name: the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Russia, and Samogitia. It was once a vast and dynamic region, playing a pivotal role in the events of the Baltic and Black Sea regions. Indeed, this was no ordinary state, and the addition of ‘Russia’ in its full title hints at the Grand Duchy's unique character, a multi-ethnic empire that fostered the cultural development of several future European countries, including modern Lithuania, Ukraine, and Belarus. In this last lecture you will learn why the union of Lithuania and Poland was necessary. And how this alliance, after resolving a centuries-old conflict, created a new one that seems to have no end in sight.

This is the third part of the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The first part can be read here. The second part can be read here.

In 1385, the union between Poland and Lithuania was concluded at Krewo Castle, located in present-day Belarus. King Władysław (Jagiełło), the founder of the Polish Jagiellonian dynasty, formally became the unified sovereign a year later. However, the terms of the union itself were so vague that they sparked prolonged disputes. Lithuania was convinced that it was a union of equals, but Poland insisted on including its eastern neighbor within its borders. The original text of the Union of Krewo is lost to history, and we know it only from subsequent accounts. So, why did all this complexity arise in the first place?

Blood Oath

The mid-fourteenth century was a time of prosperity and territorial expansion for Lithuania, ruled by the duumvirate of the brothers Kęstutis and Algirdas. Despite their successes, it was not easy for them to fight the crusaders, expand their territories in Russia, and fight the Tatars, Poles, and Hungarians simultaneously. The latter were particularly attracted by the rich lands of the Galicia-Volhynia principality,i

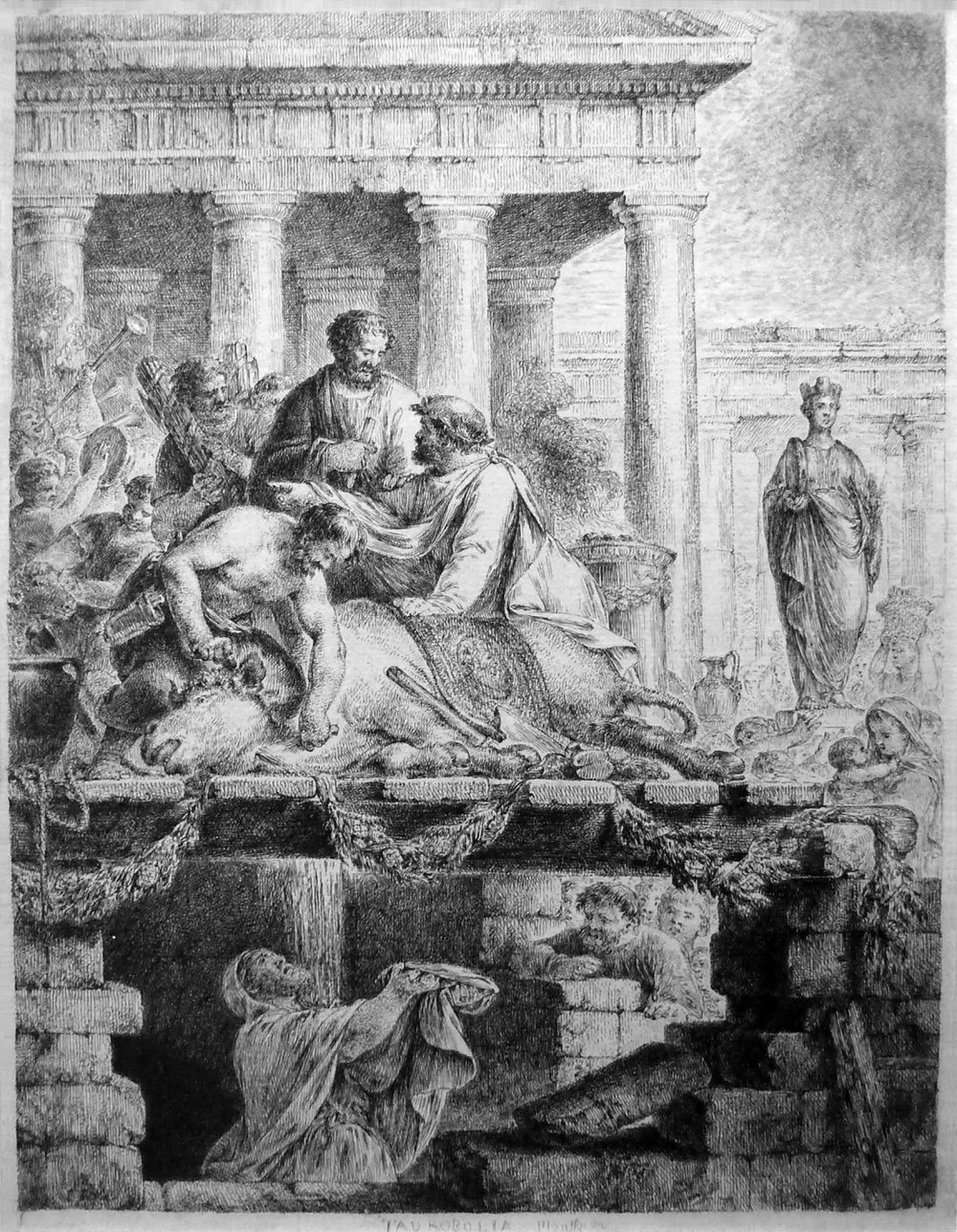

In 1351, Kęstutis asked Louis of Hungary, who was fighting for Poland, to broker peace. When the parties came to an agreement at the meeting, Kęstutis, to the surprise of those present, ordered an ox to be brought in and tied to a pole. First, he cut two veins in the animal’s back, and when its blood gushed out, he cut off its head. According to the chronicler present, the Lithuanians believed that the strong gushing of blood was a good sign. Kęstutis threw back the animal’s head and went around the circle of those present, reciting the words of the oath: ‘May it be the same with me if I break the oath …’ Then he smeared himself and his nobles with blood.

Taurobolium, or Consecration of the Priests of Cybele under Antoninus Pius. Engraving by Bernhard Rode (undated, ca. 1780)/Wikimedia Commons

What was the agreement? Kęstutis gave the Hungarians and Poles guarantees of non-aggression. But the main outcome was the creation of a coalition against the Teutonic Order and a defensive alliance against the Tartars. It is noteworthy that Kęstutis and his men, still smeared with blood, with the help of Louis of Hungary, promised to accept baptism in exchange for a royal crown from the pope. This was probably the last interstate agreement in Europe concluded in this archaic format. Kęstutis never received his crown, but the magic of integration with Poland—King Louis of Hungary would be the Polish king from 1370–82—seems to have worked, if only for the next generation of Lithuanian rulers.

The Teutonic Order: An Existential Threat

Lithuania’s relations with Poland, as with all its neighbors, were fickle in nature. War alternated with peace and peace with war. However, there was one common concern that drew the states together like a magnet: the expansion of the Teutonic Order in the north. By and large, all agreements between Lithuania and Poland were anti-Teutonic in nature. This had been the case since 1325, when the king of Poland, Władysław I Łokietek, concluded a treaty with Lithuania and arranged for his son Kazimierz to marry Aldona, the daughter of Gediminas.

Marienburg Castle viewed over the Nogat River in Malbork, Poland/Shutterstock

In the fourteenth century, the order reached the height of its power. A hundred years earlier, in 1226, the Teutonic knight Master Hermann of Salza and his team responded to the Polish Prince Konrad I of Mazovia’s request and arrived in his country to fight the pagan Prussians. This was the first bridgehead, and it was only the beginning. By the 1320s, the order was already a military and economic machine, slowly but surely grinding down the Baltic region. As a result, the order took control of the entire Baltic coast from Pomerania to the Gulf of Finland, building castles and fortified cities and bringing German colonists to new lands. As a result of the constant raids on Lithuania, an empty, deserted ‘exclusion zone’ was created one to several times a year between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the order. The number of prisoners from Lithuania was measured in the tens and hundreds of thousands.

The strategic goal of the order was to gain complete control over a bastion of paganism, Samogitia, but raids were also carried out on Polotsk land and on Black Russia, which were fairly Orthodox regions. The northern theater of military operations became popular with European knighthood; the order received ‘guests’, volunteers from all over Europe. Thus, in the 1340s, firearms were used in the region for the first time, and in 1377, the crusaders stormed the castle in Druja with artillery. Thus, Lithuania was in a state of permanent war and became a ‘European testing ground’ for 150 years. A huge but archaic state by European standards was pitted against a compact and technological military machine.

The Poles, who had invited the crusaders to the region, were also involved in this process, and the faith factor did not help here. At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the crusaders took control of Pomerania and Gdańsk. The threat was more than serious, and thus, despite other contradictions, a strong strategic alliance with Lithuania became a matter of time.

Two-faced Janus: Vytautas and Jogaila

Shakespearean passions simmered between the cousins Vytautas and Jogaila. The first was the son of Kęstutis, the second Algirdas’s. According to various chronicles, Jogaila lured his uncle Kęstutis to the castle of Krewo in 1382 and killed him treacherously. The elderly, but still strong, eight-five-year-old prince was chained, thrown into the tower dungeon, and then strangled. And this is, in a manner of speaking, the beginning of the conflict, although some historians are of the opinion that the story of the murder is ‘black PR’ by the crusaders. The same chroniclers describe the murder, for example, allegedly committed by the ancestor of the Lithuanian dynasty Gediminas, who was allegedly a stableboy of the ‘real’ prince Vytenis and traitorously killed him to take his place.

Wojciech Gerson “Kęstutis and Vytautas imprisoned by Jogaila” 1873/Alamy

This is a general problem with Lithuanian history before the Union of Krewo: we know about its events from Russian and crusader chronicles, which had every reason to present the episodes in their own unflattering interpretation. Or we know them from later sources of the sixteenth century, such as Maciej Stryjkowski’s Chronicle of Poland, Lithuania, Samogitia and all of Ruthenia (1582), where another bias is noticeable: the glorification of the past. So why was this the case?

Despite its large area, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a rather archaic state, whose development did not keep pace with its territorial growth, hence the late baptism, the problems with ‘domestic’ chronicles, and even the ‘bloody oath’ of Kęstutis. He confirmed the treaty, as he was accustomed to do, with a pagan oath.i

Vladislav II Jagiello, Grand Duke of Lithuania 1377-1381 and 1382-1392, King of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1386-1434/WIkimedia Commons

But let us return to our heroes for a moment. Even before the murder of Kęstutis, regardless of who killed him, Jogaila formed an agreement with the crusaders in 1379 and concluded the Treaty of Dubysa, a military alliance that provided for the transfer of Samogitia and the baptism of Lithuania by the order, in 1382. The expressive and successful Vytautas, wanting to seek revenge against Jogaila for the death of his father, started a civil war and did not hesitate to enlist the order’s support of the order. The prize was the same: Samogitia. In 1383, during the course of hostilities, the cousins, with the participation of the crusaders, burned half of Wilno. Jogaila, as a more calculating and balanced man, looked for a way out of the situation, which would have been a reliable ally. He considered various options: Moscow, the order, the Tatars—and the Poles.

The Poles were interested in forming this alliance because in 1382, Louis of Hungary (the one Kęstutis surprised with a bloody performance) died. He was king of Hungary and from 1370 until his death, he was also the king of Poland. He left behind a young daughter named Jadwiga. The court officials soon realized that it was possible to make the deal of the century: marry the child to a ‘barbarian’ from Lithuania and to simultaneously obtain a strong ally and put an end to the seemingly endless war for the Galicia-Volhynia principality, which had already lasted forty-five years. Thus, when an embassy from Jogaila, led by his brother Skirgaila, arrived in Kraków in January 1385, the marriage had most likely already been decided. According to some historians, the Poles deliberately ‘threw away the sword and replaced it with union. After all, why fight for Galicia-Volhynia Rus when everything could be settled by a dynastic marriage?

The next step was the signing of the union itself in August 1385 in Jogaila’s family castle in Krewa. According to the Treaty of Krewa, Jogaila, in exchange for the right to marry Jadwiga, ‘accepts the Catholic faith of the Holy Roman Church, transfers all his wealth to compensate for the losses caused by the war between Poland and Lithuania, and promises to return to Poland the lands taken from it.’ The last was the most mysterious clause: Jogaila ‘promises to annex his Lithuanian and Russian lands to the crown of the kingdom of Poland forever’. Due to this provision, much blood would be shed both during the lives and after the deaths of the main actors of the drama.

Belarus: remains of Krevo castle/Shutterstock

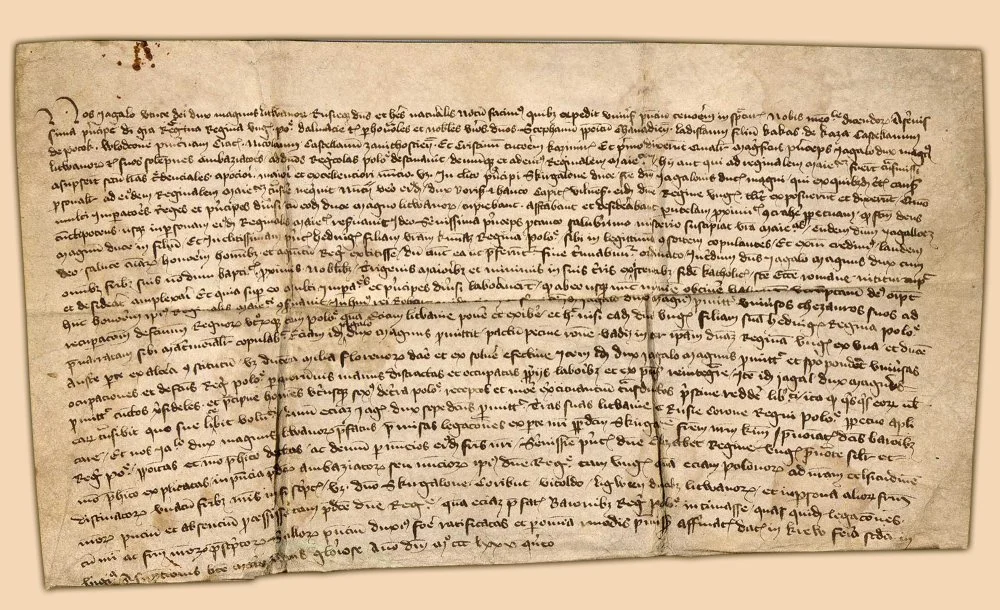

The original document of the treaty is lost, and what we have is only a copy without seals or signatures. So what was it really like? Was it a forgery? Or perhaps everyone interpreted the union as they desired: the crown as an act of annexation, Lithuania as a vassal, and Lithuania as an equal union? Some historians are inclined to believe that it was a personal alliance between the Polish state and Prince Jogaila of Lithuania. It is easy to guess why the latter needed the alliance: prestige, the throne of Kraków, the solution of internal (Vytautas) and external (the order) problems.

Treaty of Krevo: without seal and subscription.… 1385/Wikimedia Commons

But for the rest of Lithuania and Russia, including Vytautas, such an alliance promised rather dim prospects. Jogaila first appointed his brother Skirgaila as the governor of Lithuania and not his cousin Vytautas. Effectively driven out of power, Vytautas began a new round of war with Jogaila (again with the help of the order), declaring that he would lead the Russo-Lithuanian kingdom with no obligations to Poland.

However, the war ended with an agreement: Vytautas became the ruler of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania for life and was given full freedom in domestic policy, but after his death, Lithuania was to pass to Jogaila and his descendants,which postponed integration.

The seal of Witold, duke of Lithuania 1407/Wikimedia Commons

After reaching this deal, Jogaila and Vytautas decided to strike against the order. The much-coveted Samogitia had already belonged to the order for ten years, and thus, at a secret council in Nowogródek in 1408, Vytautas and Jogaila decided to get it baack through a joint effort. Thus began the Great War (1409–11), which culminated in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410. The crusaders were defeated, Master Ulrich von Jungingen was killed on the battlefield, but the order’s capital, Marienburg (Malbork), was not taken by the allied forces.

Jan Matejko, 'Prussian Homage,' 1882. The painting depicts the vassal oath of Duke Albrecht of Prussia to the King of Poland. This occasion became a turning point in the history of the Jagiellonian dynasty, paving the way for the triumph of Polish arms and Polish statehood. /Wikimedia Commons

‘An Unequal Marriage’

The union between the prince of Lithuania and the crown was essentially an ‘unequal marriage’, much like Jogaila’s own marriage to thirteen-year-old Jadwiga. A kingdom and a principality were divided into appanages. It was a Catholic power with vast territories populated by a Orthodox population and pagans. Kraków, with its university, churches, Gothic architecture and royal chancellery, coexisted with Wilno, where fortress walls appeared only in the sixteenth century, while pagan altars stood and the tradition of burning corpses persisted. Interestingly, the body of the murdered Kęstutis was brought to the capital and burned together with weapons and horses according to the old custom in 1382. Even the capital in the Grand Duchy was a fickle concept. Was it Nowogódek, Kernavė, Trakai, Wilno? Most often, the capital was where the actual Grand Duke was and from where he sent his letters and orders. If there were two places from which this was done, there were two capitals.

Michał Elwiro Andriolli.“The Murder of Keistut.” Illustrated almanac “Heritage of Belarus: history and art” 1883/Wikimedia Commons

All these practices were strange to Poland, including Jogaila himself with his relatives and boyars who came to Kraków. It is no accident that as early as the third quarter of the fifteenth century, after the death of Władysław/Jogaila himself, the historian Jan Długosz describes him as a savage who was, to put it mildly, not understood at court. He was secretive, a teetotaler, wearing black goatskin coat, no stranger to pagan customs, speaking in his own language so that the Poles could not understand him. Even the last of his wives, Zofia Holszańska, was from Jogaila’s homeland and not from the Polish nobility—it was more comfortable that way.

Naturally, a system of dividends was developed for the Lithuania and Rus boyars and nobles within the framework of the integration: they were accepted into the noble brotherhood of the Polish highborn, granted greater rights and freedoms, and they could even be legally compared to the hereditary princes of the houses of Rurik and Gediminas. Nevertheless, the alliance between Poland and Lithuania, after the order had ceased to be a real threat, still had many cracks. Until his death, Vytautas wanted to catch up with his rival/brother and become king and receive the crown from the pope. Jogaila, of course, did not allow it, and papal ambassadors were detained in the territory of Poland as long as it was necessary—until, in fact, Vytautas died in 1430.

After Vytautas’ death, a power struggle began in the Grand Duchy, and Vytautas’ brother Žygimantas (Sigismund) was killed in 1440 by the Jagiellonian representative Kazimierz (according to another version, it was Iwan Czartoryski who killed him). One of the last separatist princes was Jogaila’s younger brother Švitrigaila, who fought with Vytautas, Jogaila, and Žygimantas and ended his turbulent political career in Volhynia in the castle of Lutsk. For some time he called himself the Grand Duke of Lithuania and, relying on the nobility of Volhynia and Galicia, continued the project of the “Russian kingdom.” After his death in 1452, his body was taken to the Vilnius Cathedral and placed next to the bodies of his enemies and relatives, Vytautas and Žygimantas. At the time, the representatives of the Polish line of Gediminas, now Jagiellonians, were buried in Kraków.

Lithuanian Grand Duke Švitrigaila 16th century/Wikimedia Commons

The union was on the verge of collapse on several other occasions and was renewed several times (in 1499 and 1501). In a sense, it was a matter of correcting mistakes, compensating for the unspecified and unspoken conditions of the original union. Incidentally, the Teutonic Order, after its defeat in the Thirteen Years’ War with Poland in 1466, recognized itself as a vassal of the crown and ceded West Prussia. The last master of the Order, Albrecht Hohenzollern, accepted Lutheranism in 1525, which put an end to the ‘past of the Order’, and thus began the history of the Duchy of Prussia.

Although missionaries and priests in Prussia and Lithuania continued to be confronted with the vestiges of paganism, the ‘war of faith’ was over. Thus, the geopolitical threat that had been the cause of Lithuania’s alliance with Poland ceased to exist.

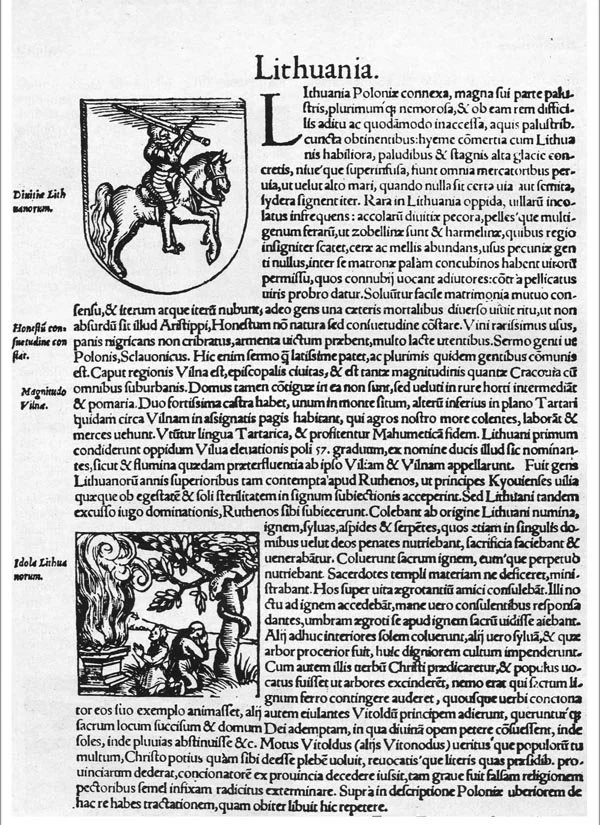

A facsimile of a page from Sebastian Münster atlas “Cosmographia universalis”, describing Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1544/Wikimedia Commons

Why Reunite in 1569?

In 1569, when the Union of Lublin was negotiated and concluded, as a result of which the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth of the two nations, already a formalized union state, appeared on the map of Europe and stayed there for more than 200 years, Lithuania and Poland were completely different states than at the time of the signing of the original union in 1385. First, Lithuania was clearly thriving. They had printing presses, a well-developed system of coins for trade, and even written laws to keep things in order. Their buildings reflected the Renaissance style popular in Europe. Interestingly, Lithuania even had its own unique story about where their royal family came from. They claimed their grand princes were descended from Roman nobility, setting themselves apart from the Polish nobility who traced their roots back to a different, nomadic people called the Sarmatians. The two states competed with each other as before, and had separate armies and economic systems, but now they had one ruler from the Jagiellonian branch who acted as king and grand duke at the same time.

The impetus for another round of rapprochement, like 200 years ago, was a great war. This time it was with Muscovy, which had gained strength and freed itself from the yoke of the Horde and began to ‘gather Russian lands’. It was the Livonian War,i

P. P. Sokolov-Skala "The capture of the Livonian fortress Kokengausen by Ivan the Terrible" /State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

At that time, in the sixteenth century, Moscow was repelled by joint efforts. But this turned out to be just another episode in the endless confrontation in Eastern Europe. In the future, there would be a Polish-Lithuanian occupation of Moscow, and a Polish king, Władysław from the Vasa dynasty, who was related to the Jagiellonians, would become the tsar of Moscow. But this wouldn’t last. Battles over Ukraine would follow, along with the devastating partitions of Poland by Catherine the Great. This period of loss is even captured in a famous polonaise by Michał Ogiński’s called Farewell to My Homeland. Today, it feels like echoes of the past are clashing with the present, like someone messed with the controls on a time machine. It's a complex relationship, with a long and dramatic history.

Here you can read the first and the second parts of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.