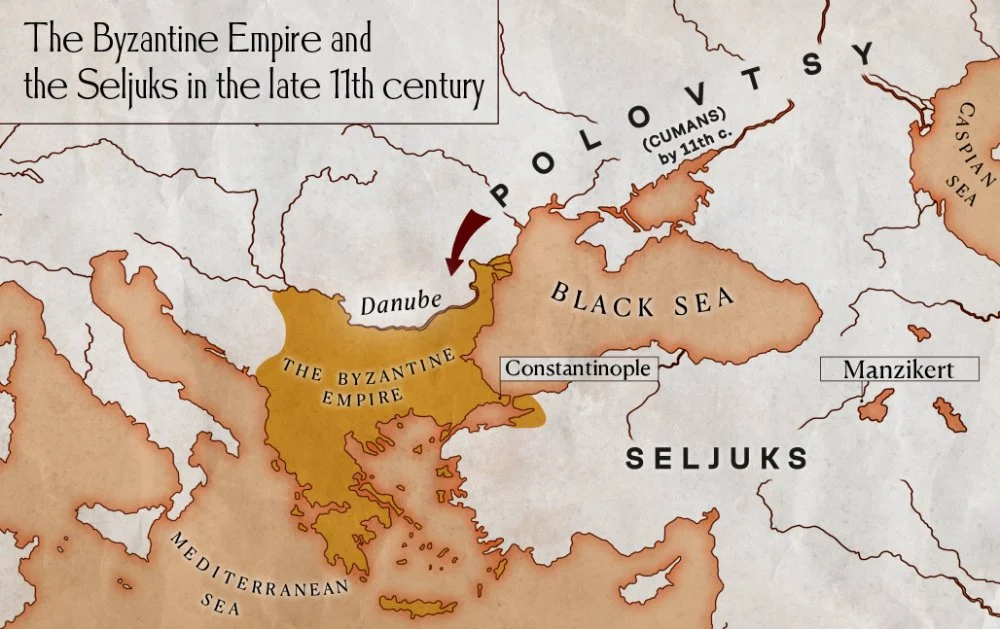

In this series of lectures, Byzantinist, Iranian scholar, and Turkologist Rustam Shukurov shows us how Byzantium interacted, engaged in conflicts, and forged alliances with the Turks, tracing the path leading to the empire's eventual downfall at their hands. The fifth lecture takes us from the north to the east of the empire, where in the eleventh century, the empire encountered the Seljuk Turks. Who are they? Why did Byzantium lose the Battle of Manzikert? Is it true that the First Crusade was organized by the Byzantine emperor? The answers to these questions are in this fifth lecture of the course.

The Byzantines did not have a single or general term for the Seljuks and referred to them by different names: Turks, Huns, Scythians, Parthians, but most commonly, Persians. The modern scholarly usage of the term ‘Seljuks’ comes from Muslim, Persian, and Arabic sources, which specifically identify the ruling dynasty in the Seljuk state. The Seljuks belonged to the Oghuz branch of the Turks. From the mid-eleventh century, the Byzantines were familiar with the Turkic Oghuz (Turkmen) tribes that raided the Balkans. Undoubtedly, the Oghuz tribes on the Danube and those from which the Seljuks originated were part of the same tribal confederation. However, the Byzantines did not know of such a connection and did not associate the Anatolian Persians with the Balkan Uzes.

The Seljuk State

In the tenth century, the Syr Darya Yabgu, an office akin to that of viceroy, of the Oghuz state controlled extensive steppe territories north of the possessions of the Bukhara Samanids—from the Volga River to Lake Balkhash in modern-day Kazakhstan. To the south, their settlement zone extended to the Aral Sea and the middle course of the Syr Darya. It is commonly believed that the Oghuz people arrived there, presumably from Mongolia or neighboring regions, no earlier than the end of the eighth century after the disintegration of the Great Turkic Khaganate. In Central Asia, other Turkic tribes, such as the Pechenegs, Khalaj, Charuk, Karluk, Eastern Turkic Bayandur, Imur, and Kai, were associated with the Oghuz confederation, which included Iranian nomadic tribes, such as the Alans and Ases. Turkic ethnic groups in the borderland areas of Central Asia, mixed with the indigenous Indo-European and predominantly Iranian population, were referred to as Turkmen. This term also referred to Islamized Turks in the borderland areas who, under the influence of the local Iranian population, had embraced Islam. The term ‘Turkmens’ was applied not only to the Oghuz people but also to mixed and Islamized groups from the Karluk, Khalaj, and other Turkic-speaking tribes dwelling in the border regions of Central Asia.

In the late tenth century, a portion of the Oghuz people, led by the Seljuk clan from the Oghuz-Turkmen tribe of Kynyk, rose in rebellion against the weakened rule of the Oghuz Yabgu. The Seljuks, who had initially served the Iranian (Tajik) Samanid dynasty in Bukhara (from the ninth to eleventh centuries), later aligned with the Turkic Karakhanid dynasty, which seized the region between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers from the Samanids in the early eleventh century. At the beginning of the eleventh century, a significant portion of the Seljuks-Oghuz came under the influence of the Ghaznavids, the rulers of Khurasan. Countless uprisings among the Oghuz were eventually consolidated under the rule of Muhammad Tughril Beg (1037–63) of the Seljuk clan. In 1040, following the famous Battle of Dandanaqan, in which the vast army of Ghaznavid Sultan Masud I was defeated, the Oghuz proclaimed Tughril Beg as the supreme ruler. In the subsequent years, the Seljuks rapidly conquered extensive territories from Mawarannahr to the borders of the Byzantine Empire in Syria and Armenia. In 1058, the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad officially conferred the title of sultan upon Tughril Beg.

As previously discussed, the Seljuks, who gave their name to the Turkic conquerors of the eleventh century, were merely the driving force behind the invasion. Only the leaders (and later the sultans) belonged to the Seljuk clan. The commanders of the right wing of the Seljuk troops were appointed from the Kayi and Bayat tribes, while the left wing consisted of Pechenegs and Chavundars. The Turkic hordes included tribes of both Oghuz and Kipchak origin.

The Seljuk Sultan Togrul III. A miniature from a Persian manuscript. 15th century / Alamy

Advances toward Byzantium

The establishment of the Seljuk state in the Near and Middle East increased Turkic pressure on the eastern Byzantine border from the 1040s to the 1070s. This coincided with a structural crisis in the empire during the eleventh century and devastating raids by the Pechenegs and Uzes on the Balkan provinces, which often threatened Constantinople itself.

Initially, the Seljuk raids followed the patterns of nomadic incursions, being localized in character and focussed on plundering the targeted areas. However, in effect, they served as reconnaissance missions to assess the empire's defenses. The main target of these raids was Byzantine Armenia. The central Seljuk authority pushed the nomadic hordes to the borderlands to protect the settled economy from their attacks. Thus, the Turkmen tribes displaced to the western border were weakly controlled by the central administration and carried out raids into Byzantine territory at their own risk.

In the following decade, parallel to the deepening power crisis in Byzantium, ethnic and religious tensions intensified between the Greeks, Armenians, and Syrians in the eastern Anatolian provinces. By the late 1060s, the east border of Byzantium was engulfed in anarchy, with the Turks freely ravaging the border regions of Armenia, Iberia, and Mesopotamia, penetrating deeper with their raids until the central parts of Anatolia, including Ani, Sebastia, Melitene, Hone, and many other cities, were under attack. The Turkmen hordes primarily invaded Byzantine territories via two corridors: through northern Syria into Cappadocia and Greater Armenia south of the Pontic region.

Meanwhile, the supreme Seljuk authority, represented by Sultan Alp Arslan (1063–72), the successor of Tughril Beg, systematically subjugated the border territories of Georgia and Greater Armenia, thus effectively providing a rear base for Turkmen raids into the Byzantine Empire's territory.

The deepening internal crisis in Byzantium led to a situation where, at the beginning of the reign of Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes (1067–71), the armies chronically suffered from a lack of essential equipment (including even weapons and horses), the Anatolian provinces endured frequent Turkic raids and uprisings by mercenaries, and tensions between the Orthodox, Armenians, and Syrians on the eastern border reached a dangerous level.

Rushing to address the situation on the empire’s eastern edge, the emperor launched a series of large-scale campaigns, leading armies composed of guard units, Balkan Scythians, Frankish and Armenian mercenaries, and militias from the eastern provinces. The Byzantines attempted to block Turkmen raids but fell short of achieving any decisive success as the Turkmen forces broke through whenever Byzantine troops were absent. It became increasingly evident that the Greeks, attempting to seal the border, were pursuing (intentionally or unintentionally) an ineffective strategy against the improvised attacks of the nomads.

In the summer and autumn of 1070, Sultan Alp Arslan invaded the Byzantine border and captured the fortresses of Manzikert and Ardjish. It appeared that he did not intend to start a full-scale war with the Byzantines. Instead, his aim was to pacify the fragmented and restless western border of his empire—the Armenian and Georgian territories, northern Syria, and Upper Mesopotamia—which had effectively fallen under the control of independent Turkmen nomadic leaders. He may have done this with the distant goal of creating a foothold for a war against the Fatimids.

600,000

The number of the Seljuk Turks settled in Anatolia during the first wave of migrations at the end of the eleventh century

In the summer of 1071, Byzantine forces under Romanos IV headed east. The emperor intended to strengthen the border in Armenia by establishing firm control over the northern shore of Lake Van. For this purpose, he sent a large part of his army to besiege Philaretos while he attacked Manzikert. By doing so, Romanos IV planned to cut off the main routes of the Turkmen incursions from Azerbaijan. With a small force, Sultan Alp Arslan decided to intercept the basileus, the emperor, stationed near Manzikert with a lesser part of his army. On 26 August 1071, Romanos IV, refusing to negotiate peace with Alp Arslan, engaged in battle with the Seljuk forces. As a result of the two-day battle, the basileus found himself in Turkish captivity, and his army was dispersed. Romanos IV spent eight days in Alp Arslan’s camp, who treated the captive with exceptional respect. After concluding a peace treaty, the emperor returned to Constantinople.

Alp-Arslan humiliates Roman IV Diogenes. Miniature of the 15th century / BNF

It was a series of unfortunate coincidences that determined the catastrophic outcome of the battle for the Byzantines. Without reliable information about the sultan's movements, Romanos IV dispersed his forces and kept only the smaller portion with him. However, some Pecheneg and Uz mercenaries, who shared ethnic ties with the Seljuks, defected to the enemy's side. And so, a battle the Byzantines had already won turned into defeat, simply because the army misinterpreted Romanos IV's return to the camp as a retreat. As the course of the battle showed, the Seljuks could not withstand the direct pressure of the Byzantine war machine, and they achieved victory only through a combination of circumstances.

The course of the Battle of Manzikert does not appear to be a straightforward consequence of the decline that had gripped the Byzantine Empire in the previous decades. From a military point of view, the Byzantine defeat was not catastrophic as the overall military potential suffered only minimal damage. However, in conjunction with the anarchy prevailing in the administrative and military affairs of the empire, it had catastrophic consequences for the fate of Byzantine rule in Anatolia. The empire, which was at the peak of a structural crisis at that fateful moment, was unable to resist the influx of the Turks into Anatolia.

Turkic raids now devastated Anatolia with renewed force, encountering little resistance from the Byzantine authorities. Following the defeat of Romanos IV, the empire fell into a long-lasting political crisis—emperors were constantly being replaced on the throne and military commanders revolted one after another in Anatolia. By the late 1070s, Turkic raiding parties operated throughout Anatolia, from Greater Armenia in the east to the Aegean coast in the west. Further, the Turks soon gained access to cities without sieges or bloody assaults—rebellious generals formed alliances with them and willingly let them into the cities as garrisons.

Malik-Shah I is on the throne. Miniature from the "Collection of Chronicles" by Rashid al-Din. 14th century / Alamy

Lost Anatolia

Masses of Turkic nomads soon flooded Byzantine Anatolia, and estimating their numbers was a difficult task. The newcomers were far fewer in number than the indigenous inhabitants of Anatolia, the vast majority of whom were Greeks and Armenians. In the mid-thirteenth century, William of Rubruck determined the numerical ratio between the local Christians and the incoming Saracens to be about ten to one, a proportion considered plausible by Claude Cahen, a great expert on Muslim Anatolia. If Rubruck's estimates even roughly corresponded to the realities of the thirteenth century (and we have no compelling reasons to reject them), then at the end of the eleventh century, the number of Muslim newcomers was even smaller compared to the local population. Referring to typologically similar examples also confirms the plausibility of Rubruck's estimates. According to the authoritative opinion of the historian Jacques Le Goff, the barbarians who settled in the Roman Empire in the fifth century constituted no more than 5 per cent of the population of the conquered territories.

Assuming that Muslims comprised only 10 per cent of the populace by the mid-thirteenth century, it is highly likely that the number of Turkic migrants in the late eleventh century could have been half as much. Warren Treadgold estimated the population of Byzantine Anatolia around 1025 to be 12 million. In that case, the first wave of Turkish migration from the east may have amounted to around 600,000 people, representing approximately 5 per cent of the indigenous population.

Half a million immigrants—an impressive number in absolute terms—becomes less significant compared to the enormous size of the local population. However, what truly matters is not how much larger the local population was compared to the invaders but rather how quickly and effectively the newcomers disrupted the communication networks within the existing administrative and economic framework. Byzantine authority collapsed precisely because administrative, police, and economic communications were paralyzed on both the macro level of provinces and the micro level of urban and rural communities. The Turkish invasion also initiated a natural population decline (through killing and enslavement) and mass migrations due to the panicked flight of local inhabitants from areas attacked by nomads. This further exacerbated and accelerated the collapse of the communication network that maintained the cohesion of Byzantine society in Anatolia.

The consequences of the nomadic migration soon manifested in the rapid depopulation of several Anatolian regions, particularly in the Central Anatolian Plateau and its outer perimeter. Moreover, the depopulation of territories occurred explosively at times due to the clash between two modes of subsistence: the sedentary agriculture practiced by the indigenous population and the nomadic pastoralism brought in by the newcomers. The regions where grain crops sustained the nomad’s herds in both winter (winter wheat) and autumn (spring wheat) were quickly abandoned by peasants, often unable to endure even a single year. The next stage of the Turkic newcomers' settlement of these territories involved their nomadization, that is, the permanent settlement of deserted lands by nomads or sedentary settlers. From an ethnocultural perspective, these processes led to the de-Hellenization (de-Armenization) of the territories and their Turkicization. Thus, the ethnic map of Anatolia gradually changed.

It is important to note that the Turkic conquerors in Anatolia were far from being a unified force. They represented separate groups, more or less numerous, and often acted independently without any political center. In the 1080s, the Turks spread throughout Anatolia and began to coalesce around several centers of power scattered across the region. The Turkic emir Sulayman ibn Qutalmish (1077–86), hailing from a junior branch of the ruling house of the Seljuks of Iran and operating in Anatolia at his own risk, firmly established himself in Nicaea. It was Suleiman ibn Qutalmish who, in addition to extending his authority over parts of Cilicia and Antioch, played a crucial role in forming the first Muslim quasi-state entity in the urbanized areas of Lesser Asia.

However, Sulayman did not overcome the essential fragmentation of Turkic Anatolia, and this became evident after he died in 1086. The center of power in Nicaea passed to Abu al-Qasim, one of the emirs and Sulayman's successor. In the following years, a slow process of political consolidation among Turkic groups began, with their power typically relying on the urban centers they had captured.

Clearly, in these spaces of power, many of which did not last long, various subethnic and tribal Turkic groups, including the Oghuz and Kipchaks, could dominate. These centers could also pursue different political and cultural strategies toward the local Byzantine population and the Constantinople authorities as we can retrospectively assume from later evidence. Thus, in this sense, Turkic Anatolia was highly fragmented at the turn of the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Traditionally, we collectively label all the conquerors who arrived in Byzantine Anatolia in the eleventh century as Seljuks. However, it is vital to remember that the overwhelming majority of the Turks hardly identified as Seljuks or even as part of something greater.

Siege of Antioch. Miniature from a 14th century manuscript / Alamy

Stabilization under the Komnenoi

In the second half of the 1080s, the newly ascended emperor Alexios I Komnenos made some progress in the coastal areas of northwest and west Anatolia, pushing the Turks farther into the mainland. However, the real turning point in favor of Byzantium in Anatolian affairs came much later, thanks to the knights of the First Crusade. The very idea of the crusade seemingly belonged to Alexios I, who systematically explored all conceivable means to save the empire and restore its power. From 1097 to 1098, the crusaders expelled the Turks from Nicaea and handed it over to the Byzantines. This exceptional success immediately shifted the balance of power in Anatolia in favor of the Greeks. The Byzantines once again occupied vital strategic points that safeguarded the western part of the empire. Around 1099, Alexios I reclaimed almost the entire Mediterranean coast of Anatolia up to Cilicia. In May 1101, the crusaders in northern Anatolia recaptured Ancyra from the Turks and gave it to the Byzantines.

Alexandre Hesse. Godfrey of Bouillon received by Alexis Comnene, Emperor of Constantinople. Circa 1879 / Alamy

However, the Turks were not broken by the victories of the crusaders and the Greeks. In the subsequent years, a protracted struggle for the western parts of Anatolia unfolded. The Turks incessantly threatened strategic strongholds along the Aegean Sea and the Propontis (the ancient Greek name of the Sea of Marmara). The Greek campaigns from 1109 to 1116 were often led by the emperor himself and were meant to stabilize the border region and protect the inner regions of west Anatolia from Turkish raids.

The military activities of Alexios I in the final years of his reign in Anatolia led to the establishment of a relatively stable border zone, which had previously not existed in these parts. From the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, the Byzantine-Turkish border was not a distinct line, like modern interstate borders, but rather a buffer zone.

Emile Signol. Taking of Jerusalem by the Crusaders on July 15, 1099. 1847 / Alamy

Undoubtedly, the establishment of this border zone positively impacted the rest of the Byzantine territories in Anatolia, which now became inaccessible to nomadic incursions and constant instability. Most of Byzantine Lesser Asia regained peace and protection, essential for the normal functioning of society and the economy.

The restoration of peace and prosperity in the fertile valleys and ports of Anatolia, along with the revival of the urban economy and agriculture, played a decisive role in restoring financial stability to the empire under Alexios I and subsequently in the rapid growth of prosperity, both in the imperial treasury and among the citizens. Within a generation or two, Byzantium would once again shine with gold, emeralds, and silks, surpassing most eastern Mediterranean nations in its economic potential and, therefore, its geopolitical possibilities.

The Anatolian Situation from the Eleventh to Thirteenth Centuries

When discussing the Anatolian situation in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, it is essential to focus not only on a single buffer zone (known as udzh in Turkish) but on a whole system of interconnected border zones. This was a relatively vast territory, mostly sparsely populated due to constant military clashes and the dominance of the nomadic tribes. However, control over these border zones was critical for both opponents, the Komnenoi and the Seljuks. These border zones were structured by dozens of fortified settlements, strongholds, and forts, which we only know of from archaeological remains. Alexios I began the construction of key fortifications in western Anatolia, accommodating several tens to hundreds of people even before the start of the First Crusade. This system of small forts, supported by fortified military bases, constituted the only effective strategy to combat nomadic incursions.

Interestingly, similar strategies to deter nomadic raids have been employed by sedentary societies throughout history. One example is the system of forts in the North American frontier zones bordering Indian territories from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries. It was a network of interconnected stations and small forts, initially surrounded by walls but eventually evolving into practically unfortified military bases during the nineteenth century. These stations and forts were strategically positioned to cover areas that had been settled by colonists and to control not only transportation arteries but also the traditional routes of hostile indigenous nomads. Apparently, a similar logic was applied while constructing the Byzantine fortifications in Anatolia.

Another example is the Russian defensive system that resisted Turkic raids on the southern borders and in Siberia. From the sixteenth to seventeenth centuries, it consisted of the so-called intersection of lines, a series of fortifications, garrisons, and settler colonies. This defense system evolved into defensive lines comprising earthworks, ditches, and forest barriers that were supported by observation points and garrisoned forts during Peter the Great's reign .

King Seleucus I with his army. A miniature from the "History of Alexander the Great". 14th century / Alamy

Consolidation of the Seljuk Realm

Paradoxically, the formation of the Byzantine borderlands contributed to the crystallization of Muslim power in the Central Anatolian plateau.

In the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, Muslim Anatolia was divided among stable Muslim principalities that managed to consolidate the diverse mass of nomads and, to varying degrees of success, redirect them from urban centers toward the emerging borderlands between Byzantine and Muslim territories. The crucial contribution to the crystallization of the Seljuk state was made by the activities of Sulayman ibn Qutalmish and later his son Kilij Arslan I (1092–1107). They established and consolidated authority over Central Anatolia with its center in Konya (Iconium). At the turn of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, another significant center of power, the Danishmendid Emirate, emerged around major urban centers in northeast Anatolia—Sivas (Sebastia), Amasya, and Niksar. The principality was founded by Danishmend (meaning ‘learned, knowledgeable, wise person’ in Persian), one of the emirs of Sulayman ibn Qutalmish after the latter's death.

In the first third of the twelfth century, the caliph in Baghdad conferred the honorary title of king (in Arabic 'malik') on Gümüshtigin, Danishmend's son (1104–1135). In the first half of the twelfth century, the Seljuks of Konya and the Danishmends fiercely competed for power in Muslim Anatolia. In addition to these two main centers of power, two other emirates emerged in the easternmost part of Asia Minor in the first half of the twelfth century: the Mengujekids with their base in Erzincan and Divrigi, and the Saltuqids with theirs in Erzurum. The Seljuks and Danishmends became the primary counterparts of Byzantine policy in the East in the twelfth century. At the same time, the Mengujekids and Saltuqids played a modest role in the greater political game, remaining in the shadows of their more powerful neighbors.

Under the successors of Alexios I—John II Komnenos and Manuel I Komnenos—the pattern of conflict remained the same. The Byzantines fortified their border regions and prepared the groundwork for the complete reconquest of Anatolia. The Greek pressure on Muslim territories intensified during the reign of Manuel I. In 1176, Manuel I launched a major campaign against Iconium, intending to penetrate the Anatolian plateau controlled by the Muslims. However, in the Civetot Valley (known as ‘Djibrilcimeni’ in Turkish), the Turks attacked the tired Byzantine army near the abandoned fortress of Myriokephalon. The Byzantines suffered significant damage, resulting in human losses and the destruction of their entire supply chain, including siege equipment for the assault on Iconium. Thus, Manuel I was forced to retreat. The psychological blow of the defeat at Myriokephalon outweighed the military losses, and the complete reconquest of Anatolia by the Byzantines was never realized.

Qalam

Two Anatolias

As a result of the events of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Anatolian region was divided into two main zones: a Christian zone dominated by Byzantium and a Muslim zone controlled by the Seljuk sultanate. In a situation similar to the one in the Balkans, the characteristics of Byzantine-Turkish military and political relations were closely tied to the peculiarities of the landscape and climate in different parts of the Anatolian Peninsula. However, Anatolia is much larger than the Balkans and, from a natural and climatic point of view, more diverse.

Anatolia is composed primarily of the extensive Anatolian plateau situated at an average altitude of 1,000 meters above sea level. The inner part of the Anatolian plateau is the Anatolian highlands, bordered by the vast Armenian highlands to the east, representing the highest and often most inaccessible part of Asia Minor. The heights of the Anatolian plateau increase from the west (800–1,000 meters) to the east (up to 1,500 meters). The plateau's most arid and rocky areas are poorly suited to or are entirely unsuitable for agriculture, but in some regions, agriculture was possible and even flourished.

The Anatolian plateau is surrounded by the Pontic Mountains to the north and the Taurus Mountains to the south. The Pontic Mountains, stretching for 1,000 kilometers along the coast of the Black Sea, reach heights of almost 4,000 meters. They descend steeply into the Black Sea for nearly their entire length, with only a few sections between the sea and the mountains comprising more or less extensive plains suitable for agriculture. The highly fertile valleys along major and minor rivers (such as the Kizilirmak, Yesilirmak, Coruh, et cetera) cut through the Pontic Mountains.

To the south, the Anatolian plateau is limited by the Taurus Mountains, a continuous range of mountain chains along the Mediterranean coast, covered with forests from the Euphrates in the east to the historical region of Caria in the west (with heights ranging from 2,000–3,000 meters).

To the west, the Anatolian plateau is adjacent to extensive, predominantly mountainous areas along the Mediterranean, Aegean, and Marmara seas, intersected by numerous rivers and often characterized by vast fertile valleys. The regions adjoining the sea, where the mountain ranges allowed, were the most urbanized areas, particularly the western part of Asia Minor and eastern Anatolia. Due to high levels of urbanization in these regions, the densest network of both primary and local roads in the region was developed.

By the end of the eleventh century, the Anatolian plateau was under Turkic rule, while Byzantine authority was confined to coastal areas of Asia Minor. The coastal lands along the Black and Mediterranean seas were separated from the central plateau by the natural barriers of various mountain ranges, which hindered Turkic incursions into coastal regions. Thanks to the Pontic and Taurus mountains, the Greeks consolidated themselves in the coastal areas of northeast Anatolia in the Pontic region, with its center in Trebizond, and in the southeast, with the Armenians and Greeks of Cilicia, who successfully repelled the Turkic attacks from the interior plateau.

In the western part of Anatolia, the geography was more complex, with fewer significant natural barriers to penetrate from the Anatolian plateau into the fertile valleys of the Aegean region and the Propontis. Therefore, defensive lines of Byzantine forts appeared here, compensating for the geographical vulnerability of the coastal valleys. These forts were built on the northern and western edges of the Anatolian plateau, where the arid plain areas, throughout the twelfth century, represented a no man's land between Byzantine and Muslim domains. These were nearly abandoned by sedentary populations and occupied by nomads. The Byzantines used these spaces as a buffer, preventing Turkic breakthroughs toward the Aegean and Mediterranean seas and the Propontis.

In turn, the Turks from inner Anatolia sought to break through this buffer to reach the urbanized valleys that were abundant with resources ripe for plunder, as they made their way toward the coast. In the second half of the thirteenth century, when the Turks finally breached this buffer, the fate of the Aegean region and the coast of the Marmara Sea was sealed, and Byzantine authority there collapsed overnight.

Musicians in the garden. Piala. late 12th-early 13th century / New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art