In this series of lectures, Byzantinist, Iranian scholar, and Turkologist Rustam Shukurov shows us how Byzantium interacted, engaged in conflicts, and forged alliances with the Turks, tracing the path leading to the empire's eventual downfall at their hands. The sixth lecture delves into the drastic advance of the Seljuk Turks in Anatolia, which by the fourteenth century nearly resulted in its loss for Byzantium.

After the events of 1203–04 and the fall of Constantinople to the attacks of the crusaders, Byzantium disintegrated into three rival states: the Empire of Nicaea, the Empire of Epirus, and the Empire of Trebizond. Further, the Armenian Cilicia in the southeast of Anatolia, where the Armenians had recently proclaimed their own kingdom, gained full independence from Byzantium. This, it seems, should have weakened the position of the Byzantine world in the face of Turkic tribal confrontations. However, the circumstances were such that the catastrophe that befell Byzantium did not immediately and directly affect the course of the Greek–Turkic rivalry.

By the turn of the twelfth century into the thirteenth century, the Seljuk Sultanate, the most powerful state in Muslim Anatolia, faced a period of instability and internal turbulence. The powerful Sultan Kilij Arslan II, shortly before his death, divided his possessions among his nine sons, a brother, and a nephew. The sultan had distributed land according to the inheritance laws of his grandfathers, then common among the nomads of the Turkic steppe but hardly suitable for settled society, thus condemning the sultanate to years of internal strife. Signs of stabilization appeared only in the early thirteenth century when one of his sons, Rukn al-Din, consolidated almost all the fiefdoms under his power. When Rukn al-Din Suleiman suddenly died in July 1204, his young son Kilij Arslan III, who lacked the support of the nobility, reigned for just over six months. However, the power and position of the sultanate was only strengthened from 1205 with the secondary reign of one of Kilij Arslan II's sons, Ghiyath al-Din Kaykhusraw I (1205–1211).

With the rapid consolidation of power in the Nicaea and Trebizond empires, the Greeks in Anatolia succeeded in stabilizing and strengthening the border that had been breached in previous decades. They established a reliable barrier to the nomadic invasions deep into their territory. However, the paradigm of the relations between the Turkic neighbors and the two centers of Byzantine power was quite different. The Empire of Trebizond had been in conflict with the Seljuk Sultanate since its earliest days as it affected the sultanate's commercial and political interests on the Black Sea. On the other hand, the Nicaeans were largely allies of the Seljuks. There were many reasons for the Nicaeans and the Seljuks to develop mainly peaceful relations, including deep personal ties between the Greek and Seljuk elites and even cultural affinity. However, the friendly relations between the Byzantine and Seljuk nobility did not alleviate the belligerence of the nomads in the borderlands. Their attacks on Byzantine lands continued, albeit with less intensity than in the first half of the twelfth century.

Tintoretto. Conquest of Constantinople by the crusaders in 1204. 1580 / Alamy

The Seljuks are taking over the ports

Despite the relatively low military activity on the borders and the successful consolidation of local power centers in Nicaea and Trebizond, an important turning point in the strategic position of the Anatolian Turks occurred in the first two decades of the thirteenth century. This turning point largely foreshadowed the complete displacement of the Byzantines from Anatolia. The Seljuks managed to break through to the coasts of the Mediterranean and Black Sea, gaining a foothold. In 1207, Ghiyath al-Din Kaykhusraw I responded to the complaints of offended merchants and seized Attalia (Antalya), which had belonged to the Hellenized Italian family of Aldobrandini since around 1204. With the conquest of Attalia, the Seljuks broke through to the Mediterranean Sea, thus severing the link between the Greeks and the Armenians of Cilician Armenia in southern Anatolia.

In 1214, the Seljuks captured the strategically important military and commercial port of Sinop in the southern Black Sea from Trebizond. This loss resulted in the division of Byzantine rule in Anatolia into two major enclaves that were isolated from each other: Western Anatolia and the Pontic region. The Byzantines could no longer threaten the Muslim urban centers, such as Konya, Kastamonu, Gangra, and Ankara, on the Anatolian plateau. Instead, in the former borderlands, Turkmen nomadic emirates consolidated their hold on Byzantine territories in the mid-thirteenth century. The Anatolian plateau, with its major urban centers, became completely inaccessible to the Byzantines. As a result, both the western Anatolian and eastern Anatolian enclaves of the Byzantine civilization were firmly blocked by the nomadic forces, and the Greeks finally lost their chances of reconquering Anatolia, a goal that had seemed attainable throughout the twelfth century.

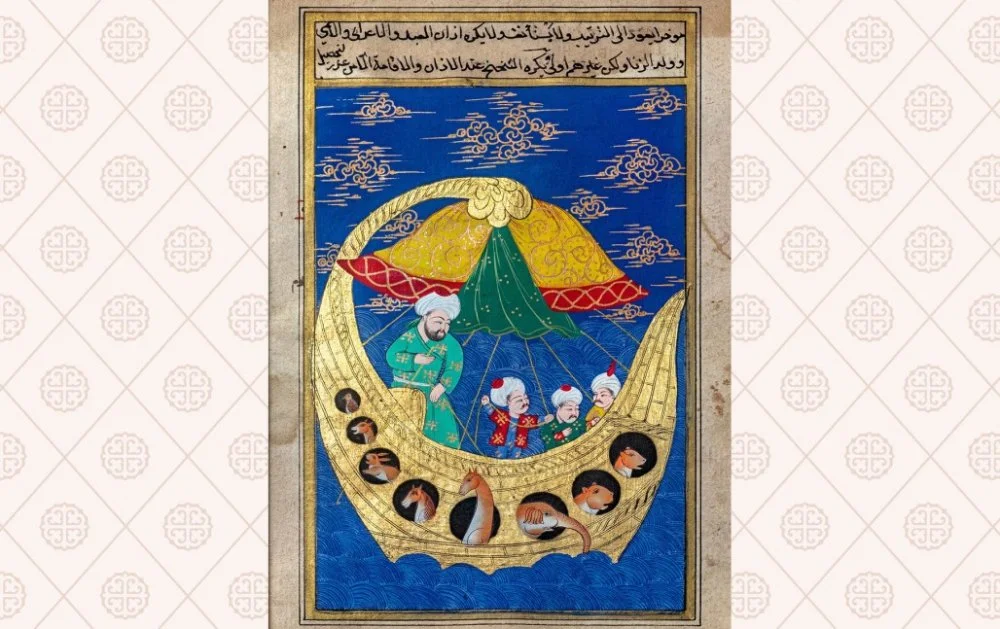

Noah's Ark. A miniature from an Arabic manuscript of the Seljuk era. 13th century / Alamy

The Second Wave of Migration

In the early thirteenth century, the destructive effects of the first wave of nomadism gradually began to fade. While many nomads transitioned to sedentary life, others suffered fatal losses in their conflicts with the Byzantines in the west and north of Anatolia, the Armenians in the south, the Georgians in the northeast, and even the Seljuks in the sedentary regions of mainland Anatolia. However, driven by the Mongol invasions, a new wave of nomadic migration to Anatolia began in the 1230s. Numerous Turkmen and other Turkic tribes, forced from Eastern Turkestan, Central Asia, and Iran by the Mongols, once again flooded into Asia Minor. They arrived in Anatolia with equally devastating consequences for the sedentary Muslims in the agricultural areas, as well as for the local Greeks, Armenians, and Georgians. Waves of nomadic tribes traversed Anatolia from east to west, disrupting traditional ways of life and leading to the nomadization of territories, just as they had done a century ago. Along the Seljuk-Nicaean border, the nomads reached a high concentration in the 1250s and 1260s, seemingly blocking the end of the Anatolian corridor—the Byzantine border.

In the 1230s, the Mongols appeared on the eastern borders of Anatolia, significantly altering Nicaean-Seljuk relations. Faced with the advancing Mongols, the two powers found themselves converging. A Nicaean contingent took part in the Battle of Köse Dağ on 26 June 1243, between the Seljuks and the Mongols of Iran, but the combined forces suffered a crushing defeat. The Seljuk Sultanate soon became a puppet state of the Mongols of Iran, who established the Ilkhanate in northeastern Iran (Maragha, Sultania, Tabriz) in 1256. In this situation, the Nicaeans, still in contact with the Mongols, continued to support the Seljuk Sultanate, seeing it as a barrier between their own dominions and Mongol-controlled Iran.

The Battle of Köse-dag 1243. Miniature from the Vertograd of Histories of the Countries of the East by Getum Patmich. 14th century / Alamy

These new developments in Byzantine-Turkic relations coincided with a radical change in Byzantine politics. In July 1261, Alexios Strategopoulos, a notable Nicaean commander, launched a surprise raid on Constantinople with a limited unit of Byzantines and Scythians. In August 1261, Nicaean emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos solemnly entered the city, and the patriarch returned, marking the restoration of Byzantium.

Upon their return to Constantinople, the Byzantines shifted their focus from the eastern provinces of the empire. They sought to restore the empire's position in the Balkans and regain prestige in Western European politics. Meanwhile, the nomads who had invaded Anatolia and gathered in the Byzantine border regions increased pressure on the Greeks and actively occupied fertile valleys in western Asia Minor. From the 1260s, the Byzantines, along with the Seljuks and the Mongols of Iran, attempted to defeat the nomads, yielding temporary results. The numbers of the nomads continued to grow, making it increasingly difficult to control them. In the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, Constantinople's belated attempts to reclaim strategically important points in western Anatolia ended in disaster. By the first decade of the fourteenth century, Byzantium had lost western Anatolia, except for small enclaves.

Portrayals of the Seljuks

The Mongols of Iran turned the Seljuks into puppets, and a powerful wave of migration from Iran to Anatolia radically changed the demography and culture of the region. Thus, the Seljuk period of Anatolian history came to a close in the last decades of the thirteenth century. The relations between the Byzantines and the Anatolian Turks over almost two centuries left a lasting impact on Byzantine traditions. This influence can be seen in the long list of Anatolian figures who played prominent roles in Byzantine life, their influence on Greek high culture and everyday existence, and the incorporation of numerous ‘barbarian’ words into the Greek language. While a detailed analysis of these influences is beyond the scope of our discussion, I will outline the typology of individuals and significant interactions, providing some examples for clarity.

The Byzantines appeared quite impressed by Anatolian Muslim leaders, some of whom had visited Byzantine territories. As early as 1093, the powerful and militant Seljuk emir Abu al-Qasim, who had Nicaea as his capital and controlled the western and central parts of Anatolia between 1084 and 1096, visited Alexios I Komnenos in Constantinople. Seljuk Sultan Malik-Shah (1110–16) also visited Constantinople after making peace with Alexios Komnenos I. Moreover, the next Sultan, Masʽud I (1116–55), became the first among all Muslim rulers of Anatolia to flee to Constantinople as a political exile.

A classic example of the Byzantine historians' vivid descriptions of a Seljuk sultan is found in their portrayal of Kilij Arslan II from his official visit to the court of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos. The Byzantines recognized the luck and managerial talents of the sultan, considering him a serious adversary. However, Choniates, a well-known Byzantine historian, depicted him as secretive, double-hearted, treacherous, cruel to his royal relatives, greedy for wealth, and eager to plunder and seize Byzantine lands.

In 1161, Kilij-Arslan II decided to visit Constantinople to conclude a long-term peace treaty with Basileus Manuel I Komnenos. Manuel I saw this visit as a great success, enhancing the glory of the empire. The plan was for Manuel and Kilij Arslan to enter Constantinople together as part of a magnificent triumph, involving nearly all of the city's residents. However, this endeavor failed. Patriarch Luke Chrysoberges opposed the Muslim Sultan's participation in the ceremony as it should have included Christian symbols, such as images of saints and Christ, church banners, et cetera, according to the Byzantine palace protocol. A strong earthquake that struck Constantinople shortly before the ceremony was regarded as a bad omen, seemingly confirming the patriarch's position. The Byzantines, who were sensitive in matters of faith, refused to hold a triumph involving a Muslim, which was quite typical of them.

View of the Hippodrome and the Great Palace of Constantinople. Reconstruction / Antoine Helbert

Nevertheless, the reception of Kilij Arslan II in Constantinople was characterized by unprecedented luxury, befitting the magnificence of the event. Manuel gave the sultan his first audience while sitting on a luxurious golden throne that rose high above the floor, adorned with precious metals and stones. The emperor wore a scarlet robe adorned with rubies and pearls, and a precious stone the size of an apple hung from a golden chain around his neck. Rows of senior dignitaries, dressed in splendid ceremonial gowns, stood on each side of the throne. Struck by such magnificence, Kilij Arslan, according to a Byzantine author, reluctantly took a low seat and only sat on it after much persuasion. In this episode, Manuel continued the long-standing strategy of Byzantine sovereigns, wherein the first audience was considered the most important and aimed to psychologically assert the empire's dominance over foreign visitors.

During their time together, the two sovereigns enjoyed feasts in the grand palace located in the southern part of the city, amusing themselves by burning small boats with Greek fire, indulging in horse races, and viewing various other entertainments at the hippodrome. An astonishing incident at the hippodrome is mentioned in Byzantine accounts. A Muslim from Anatolia decided to jump from a great height while wearing a loose, wide shirt with multiple stitches and willow rings that created broad folds. He believed that this suit would allow him to glide smoothly over the arena, covering a distance of about 400 meters or more. He intended to achieve the same gliding effect as wingsuit jumpers do today. The Saracen jumped from one of the highest points of the hippodrome: the tower above the Carceres, the monumental entrance gate decorated with the Triumphal Quadriga. He waited for the right wind, raising his hands as if to catch the air in the folds of his suit. The assembled spectators were skeptical of his venture, joking about it. Manuel I, through his servants, however, tried to dissuade the daredevil. Finally, the Saracen jumped, stretched like a bird, and predictably crashed. However, the experiences of modern wingsuit jumpers suggest that the Saracen may have succeeded in previous attempts as there are striking similarities between his outfit and modern wingsuits. The cruel Constantinople crowd mocked the unsuccessful jump, continuing to mockingly remind the sultan's retinue of the Saracen's failure.

St. Mark's Quadriga. Sculpture. Bronze. 4th century BC / Wikimedia Commons

Manuel I sought to psychologically intimidate the sultan through this demonstration of luxury. He filled a palace chamber with expensive gifts, such as precious coins, clothes, and dishes. He brought the sultan into this chamber and asked him what he desired from this wealth. The sultan humbly replied that whatever the emperor gave him would be enough. Manuel continued the game, asking whether any enemy could resist the Roman Empire if he, Manuel, decided to hire and equip an army using all these treasures. The sultan, amazed, responded that if he himself possessed such treasures, he would be able to deal with all his enemies. Upon hearing this expected answer, Manuel triumphantly announced that the entire contents of the chamber would be gifted to the sultan. Kilij Arslan, with the help of these excessive gifts, soon defeated his Muslim rivals in Anatolia, expanded his territories to the border with Syria, and united vast lands under his rule. The people of Constantinople were known for their sharp tongues, and during Kilij Arslan's visit, the emperor's cousin and future Basileus, Andronikos I Komnenos, stood out the most. He was a brilliant aristocrat, intellectual, successful warrior, ladies' man, and well-known wit. Kilij Arslan had physical disabilities, including a limp and experiencing pain in the joints of his hand. Andronikos made fun of this by altering the Byzantine pronunciation of Kilij Arslan's name from ‘Klitsaslan’ to ‘Kutsaslan’, which meant ‘lame Arslan’.

Byzantine descriptions of other Seljuk rulers also survive. Two sultans who sought political asylum in Constantinople, Ghiyath al-Din Kaykhusraw I (from 1196) and his great-grandson Izz al-Din Kaykaus II (from 1262), are described in greater detail. Ghiyath al-Din Kaykhusraw, upon his arrival in Byzantium, was baptized (or rebaptized) by the emperor and married the daughter of Byzantine aristocrat Maurozomes. Izz al-Din Kaykaus II, along with his entire family and many thousand subjects, including nomadic Turks, moved to Byzantium. Kaykaus gained notoriety in Constantinople for his frequent bouts of drinking. His children, and perhaps even he himself, were baptized. Three of his offspring remained in Byzantium after their father fled to the Golden Horde. Another son, Masud, became one of the last sultans of the Seljuk dynasty.

Byzantine society included many noble Muslims who had defected to the Greek side and became what we call Byzantine Turks. One of the early noble defectors was the high-ranking Turkic emir Erisgen, known as Chrysoskoulos by the Byzantines. He was the brother-in-law of the sultan of Great Seljuk Alp Arslan, having married his sister. In a clash in Sebastia in 1070, Erisgen captured the Byzantine commander Curopalate Manuel Komnenos, the elder brother of the future Basileus Alexios I Komnenos. However, Erisgen fell out with Sultan Alp Arslan, and, upon the advice of his captive, Manuel Komnenos, he switched sides and joined the Byzantines. Erisgen went to Constantinople with Manuel, where the emperor received him and granted him the honor of prohedria, or one who has the privilege of sitting in honored theater seats. Despite his young age and short stature, which resembled that of a Scythian, he easily assimilated into Byzantine life. He later gained fame for his involvement in the uprising led by future Emperor Nikephoros III Botaneiates in 1077–78. When the acting Basileus Michael VII Doukas sent hired Anatolian Turks to suppress the rebels, Chrysoskoulos negotiated with them, convincing them not to intervene.

Greek fire

Under the rule of Alexios I, several emirs defected to the Byzantine side during a campaign. Emir Ilkhan, who had captured important strongholds in western Anatolia, suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Byzantines and switched allegiance. Two other Turkic emirs from Ilkhan's entourage, witnessing the generosity bestowed upon him, also joined the Greek side and were rewarded with ranks and gifts. One of them, Scaliarus, became a Byzantine commander and participated in numerous campaigns. The other emir's name has not been preserved in any records, but he received a high title in the Byzantine provincial administration. Scaliarus faithfully served the emperor until his death at the hands of the Normans, specifically Bohemond of Taranto, during the Norman siege of Dyrrhachium in 1108.

In the thirteenth century, several nobles of Anatolian origin, including sultans and meliks, joined the highest echelons of Byzantine society. They were related to the ruling house of the Pailaiologos and other aristocratic families that owned vast lands, and their seamless integration into the Byzantine elite was facilitated by their lineage from the Anatolian Seljuk sultan’s family.

These are just a few examples of foreign nobles adapting to Byzantine society and, notably, to the Byzantine elite class. Noble Muslim defectors were not uncommon in Byzantium. Turks and other outsiders sought not only high positions in society and the accompanying wealth but also to immerse themselves in a different, refined, and elegant way of life. In all these cases, the primary and unchanging condition for non-Christians, whether pagans or Muslims, was conversion to Christianity. Among the Anatolians who successfully adapted to Byzantine society were many individuals from the lower social classes. Notable examples include former slaves who experienced remarkable careers in the empire. Perhaps the most extraordinary example is John Axouch (died 1150), a renowned courtier who was captured in Nicaea as a child when the Byzantines and the crusaders took the city in 1097. Alexios I took him under his care and appointed him as a companion to his son and successor, John. Axouch ascended to the pinnacle of the Byzantine hierarchy under John II Komnenos when he was given the title of Sebastos, an honored title in the Byzantine court. He was appointed Grand Domestikos of all the East and the West, effectively the commander-in-chief of the entire army, under Manuel I.

John Axouch proved himself as an experienced politician and talented commander, fighting on almost all of the state's frontiers and even leading maritime campaigns to Sicily and Kerkyra. He was also well-versed in intellectual pursuits and developed friendships with Constantinople's theologians and rhetoricians. Several seals bearing John Axouch's name have been preserved, which is understandable given his prominent position in the empire for many decades. Based on these seals, it is apparent that Saint Demetrius, consistently depicted on the obverse of the coins, was John's patron. The seals of Axouch bear identical inscriptions: Saint Demetrius on the obverse and John, Sebastos and Grand Domestikos of the entire East and the West, on the reverse.

John Axouch became the founder of the well-known aristocratic Axouch family, which had ties to the ruling house of Komnenoi. His son, the Protostrator Alexios Axouch, was a prominent commander and close associate of Manuel I. However, he fell into disfavor for adorning his house with paintings depicting Kilij Arslan's military victories. Alexios's son John Komnenos the Fat nearly overthrew Emperor Alexios III Angelos in July 1200. This family is particularly significant because their bloodline flowed through the veins of the great Komnenoi, the rulers of the Empire of Trebizond. The founder of the Empire of Trebizond, Alexios I, the Great Komnenos, was married to Theodora Axouch, the daughter or niece of John Komnenos the Fat. Their eldest son, Emperor John I of Trebizond, was also known as Axouch.

Frit porcelain bowl. Iran, late 12th century / David Collection Museum, Copenhagen

A significant number of former Anatolian Turks also served as mid-level officers and ordinary soldiers in the Byzantine Empire. They formed special units known as Persians in the thirteenth century. Moreover, some served under the leadership of the first generation of noble Byzantine Turks or their descendants. Most Byzantine Turks became soldiers in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, with only a minority pursuing intellectual and spiritual paths. This can be attributed to their relatively lower levels of education, as immigrants found it more challenging to obtain a good education, and the Byzantines did not prioritize educating them, often assigning them to non-intellectual professions.

The influx of Persians into Byzantine society continued into the thirteenth century. For the most part, these belonged to traditional categories of society, nobles and military personnel who received ranks and pronoia (grants) from the Byzantines. And during this time, several intellectuals emerged from their midst. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Byzantine fashion was enriched with numerous Eastern (Persian and even Mongolian) elements, such as caftans, robes, and various headdresses such as turbans (Persian) and saraguch (a Mongolian headscarf).

Of course, the nobility accounted for a minority of the total number of Anatolian migrants, an overwhelming majority of whom were ordinary people. However, this so-called voiceless majority are the most poorly studied people, especially for the eleventh to twelfth centuries. As a rule, the Byzantine authorities sought to disperse ignorant foreigners among their population to accelerate their assimilation. However, in some cases, captives and immigrants from Anatolia might have been settled either in compact groups or in some limited areas. Here is a textbook example of such a settlement in the twelfth century. A large group of Persians from Anatolia lived in an area in Thessaloniki in approximately 1178. These were women workers who had been enslaved and exported from Muslim Anatolia and were engaged in some kind of craft. It should be noted that the capture and removal of civilians, primarily children and women, from their lands was a widespread practice in Byzantium. Civilian captives would be enslaved and sold in slave markets or made house servants for their masters.

Much more information is available about Anatolian immigrants who lived in compact settlements in the period after the end of the thirteenth century. They were settled in certain parts of Macedonia, and they could be free peasants, paroikoi (non-proprietary migrant) peasants, or military men who received grants in those areas.

Left: Human head in beaded headdress. Central Asia. 12th-13th century / Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY; Right: Human head with pointed hat. Central Asia. 12th-13th centuries / Alamy

Peculiarities of the Muslim Invasions from the East

The Seljuk invasion of Anatolia in the eleventh to twelfth centuries differed significantly from the usual paradigms of earlier barbarian conquests known to the Byzantines. The paradigm of the Persian and Arab wars (fourth and tenth centuries) featured a clash with settled conquerors, who had a professional army similar to that of the Byzantines. The barbarian invasions (by the Goths, Slavs, Avars, Pechenegs, Cumans, et cetera) of the Balkans were nomadic raids and mass migrations of nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples. In the Seljuk Turks, however, Byzantium saw a complex combination of nomadic migration and sedentary conquest techniques. A professional enemy army confronted Byzantium, distinct from the nomadic tribes that were uncontrollably spreading over vast territories in search of pastures and booty. However, the essential feature that distinguished the Turkic invasions of Anatolia from the usual nomadic raids (known, for example, from the Balkans) was the greater structural complexity of the Seljuk conquests. Nomads were only one of the elements of the migration wave. Besides the nomads, Iranians, Arabs, and settled Turks with a significant potential for social and political self-organization entered and settled in Anatolian cities.

First Crusade 1096-1099 / Alamy

The conquerors from the East by no means avoided cities or city life, as was the case with the Pechenegs, Uzes, and Cumans in the Balkans. Relying on conquered urban centers, the Seljuks began to build a sedentary Muslim statehood in Anatolia as early as the last decades of the eleventh century. The presence of a Muslim urban state-forming substratum in Anatolia undoubtedly made it extremely difficult for the Byzantines to reclaim their lost lands. The sedentary Muslim states in Anatolia gave nomadic conquests special power by guiding arrays of nomadic invasions and strengthening their success by annexing new lands. The underestimation of the structural complexity of the Turkic invasion of Anatolia was one of the reasons for the Byzantine failure to reconquer Anatolia.

The first wave of nomadic migration covered Anatolia at the end of the eleventh century, which led to the depopulation, nomadization, and subsequent Turkification of vast areas of Anatolia, especially along the perimeter of the central Anatolian Plateau. However, in the twelfth century, the Komnenoi succeeded in stopping the nomadic expansion and regaining many of the lands they had lost.

Teacher and students. Dish. Iran, 12th century / Alamy

The second wave of nomadic migration, initiated by the Mongol conquests, filled Anatolia with new hordes of nomads and sedentary Iranians who settled in cities. Moreover, the nomads outnumbered not only their contemporary sedentary immigrants but also those Turks who entered Anatolia in the eleventh century. The nomads brought a powerful disorganizing impulse that instantly destroyed the usual lifestyle and, most importantly, the Iranian-Greek symbiosis that dominated the region. Neither the Seljuk power, extremely weakened by the Iranian Mongols, nor the Byzantine Palaiologos, which had just begun to restore the empire after the expulsion of the Latins from Constantinople, could resist this destructive wave. At the end of the thirteenth century, a completely new situation emerged in this space: vast territories were divided between small and medium-sized emirates headed by the Turks who were nomads previously. Asia Minor started experiencing a deep crisis, which manifested itself in extensive nomadization, economic and cultural regression, and a change in previously established ethnic and demographic patterns. The era of the beyliks began, which eventually made most of Anatolia Turkic. A new page opened in the history of the region, marking the beginnings of modern Turkey.