In this series of lectures, Rustam Shukurov, a Byzantinist, Iranologist, and Turkologist, narrates the story of how Byzantium encountered, clashed with, and formed alliances with the Turks, ultimately meeting its demise at their hands. The third lecture initiates discussions about a pivotal era in Byzantium's relations with Turkic peoples, commencing in the eleventh century. At the core of the narrative are the Pechenegs.

In the eleventh century, Turks made advances through Byzantine borders in two powerful streams, which we shall refer to as (1) the northern stream, which traversed the northern Black Sea region to the Danube and further to the Balkans; and (2) the eastern stream, which moved through northern Iran into Armenia, Syria, and onward to Anatolia. While Turkic and allied tribes had explored the northern route since the time of the Huns, Byzantium had, with a few exceptions, not encountered a Turkic threat along the eastern direction until the eleventh century. This was because there were no stable sedentary state formations capable of stopping the eastern nomadic invaders within the expanses of the northern steppe, which the Byzantines referred to as Scythia. On the eastern route, the dominant sedentary civilizations (Sasanian Iran, followed by the Muslim Caliphate) acted as a shield, safeguarding the Byzantine border from nomadic incursions. The situation changed only in the mid-eleventh century, when the nomadic Turks, consolidated under the Seljuks, broke into northern Iran and soon reached the Byzantine frontier.

The Byzantine army proved ineffective against the nomadic military tactics of the turks, which resembled more like "guerrilla warfare"

However, it is important to note that just like in the early Middle Ages, the hordes of the Pechenegs, Uzes, and Cumans flooding the Balkans and the Seljuks invading Anatolia were not ethnically homogeneous. There could easily be nomadic, semi-nomadic, and even settled Indo-European peoples (such as Alans, Vlachs, and Persians) among them, who, for various reasons, found themselves ruled by Turkic leaders.1

It is clear that within the coalitions of the Pecheneg, Uz, and Polovtsian tribes, the Turks still constituted the overwhelming majority, unlike in the preceding era. This is indicated, in particular, by the fact that neighboring peoples linguistically identified them as speakers of Turkic dialects.

Why Byzantium Was Losing

The beginnings of the Turkic invasions from both the north and east aligned with a fundamental political and economic transformation within the Byzantine Empire. This period also coincided with somewhat of a demilitarization of the economy that began shortly after the death of Emperor Basil II (976–1025). Under Basil, the empire had reclaimed the Balkans from the Bulgarians in the west and parts of Armenia and Syria from the Muslims in the east, reaching the natural limits of its expansion at the time. Any further expansion to the west and east seemed neither feasible nor expedient. The empire inevitably entered a period of stabilization, and a vast field army was no longer necessary. The militarized economy, geared toward addressing the significant military tasks inherited from Basil, no longer met the empire's pressing needs. His successors did not pursue—quite justifiably—such ambitious conquest plans. Military officials were gradually replaced by civilian administrators in provincial administration. Simultaneously, attempts were made to reform the military machine, but these were sporadic, intuitive, and inconsistent. Funding for the army was reduced, the size of the troops decreased, stratios units were transformed back into regular peasants. The critical border zone in Greater Armenia also underwent this type of demilitarization, which proved fatal for Byzantine Anatolia with the advent of the Seljuk raids.

In addition, professional mercenaries began to play a more prominent role, replacing the traditional militia.2

The intensification of this systemic crisis during the reign of Constantine IX Monomachos (1042–55) in the mid-eleventh century, the monarch primarily responsible for the demilitarization of the country, was exacerbated by powerful simultaneous Turkic strikes from the north and east. And so, Byzantium found itself caught between a rock and a hard place. The Byzantine military apparatus and diplomacy struggled to adapt to the peculiarities of nomadic invasions. Their field units proved ineffective against the nomadic military tactics of the Turks, which resembled ‘guerrilla warfare’ conducted by small, mobile groups of warriors. In many cases, Byzantine diplomacy suffered setbacks as the Turkic groups pouring into the Balkans and Anatolia in the eleventh century were not united under centralized policiesi

J.W. Waterhouse. Emperor Honorius's favorites. 1883 / Alamy

As we will see in this lecture, one cannot accuse the Byzantines of being utterly defenseless in the face of the nomadic threat. As mentioned earlier, throughout their history, the Byzantines had dealt with nomads, especially along their Danubian frontier, and these experiences were recorded in military treatises and diplomatic guides. However, the peculiarity of the eleventh century lay in the unpreparedness of the state machinery to withstand large-scale and long-lasting nomadic attacks coupled with the extraordinary force of the nomadic migratory wave. Additionally, from the second half of the eleventh century, Byzantium also found itself fighting the nomads on two fronts simultaneously (the Balkan and Anatolian).

Moreover, the influence of the Normans in Byzantine Italy3

These circumstances were the key factors behind the severe defeats of the empire against the nomadic Turks in the Balkans and the strategic failure on the eastern Anatolian border. The state machinery of the empire was overwhelmed, both internally and externally.

Prosper Lafaye. Roger I of Sicily at the Battle of Cerami. 1860 / Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/ Getty Images

Let’s Start with the Situation in the Balkans

For the Byzantines, the natural boundary of their world to the north was the Danube River, and thus the deployment of the imperial army to the lower reaches of the Danube during the reign of John I Tzimiskes (969–976) and its subsequent consolidation had strategic and ideological significance. From the late tenth to early eleventh centuries, the Byzantines restored the frontier Danubian fortresses and cities in the lower and middle courses of the river. These locations played a vital role as both military and crucial trading hubs, attracting merchants from the vast central and eastern European regions. Adjacent to the southern bank of the Lower Danube were the extensive plains of Paristría, also known as the Danubian or Moesian Plain. During this period, the administrative and economic map of the eastern Balkans was significantly influenced by the presence of nomads on the Danube and their desire to head south into the realms of developed urban and agricultural civilizations.

The defeat of the Bulgarian kingdomi

Nomads

The Pechenegs

The ethnogenesis of the Pecheneg tribes seems to have occurred in the Aral region, in close interaction with local Iranian nomadic tribes including the Alans. It is possible that the Pecheneg community was initially predominantly composed of Iranian nomads who, at some point, adopted the Turkic language. Craniology,4

From the mid-ninth century, the Pechenegs advanced westward from the Aral region due to various wars with the Uzes (Oghuzes), Khazars, and Hungarians. By the mid-tenth century, they approached the Prut River and the Danube estuary. As long as the Pechenegs did not come into contact with the borders of their empire, they were regarded by the Byzantines as important intermediaries for trade with the north and, to an even greater extent, as a powerful political force whose alliance would help protect Byzantium from its northern enemies.

Exploring the Life and Beliefs of the Pechenegs

Before their appearance on Byzantine territory, the Pechenegs, as claimed by Greek authors, were pagans. However, the precise nature of their paganism is difficult to ascertain. There is information that at some point in the recent past, a portion of the Pechenegs converted to Islam. However, it is unlikely that the nomads who crossed the Danube were Muslims. They may have practiced shamanism; it is not impossible that they had Manichaeans—a religion they might have adopted during their time in Central Asia—among them.5

Regarding the daily life and appearance of the Pechenegs, the Byzantines wrote very little. An extensive passage by Michael Psellosi

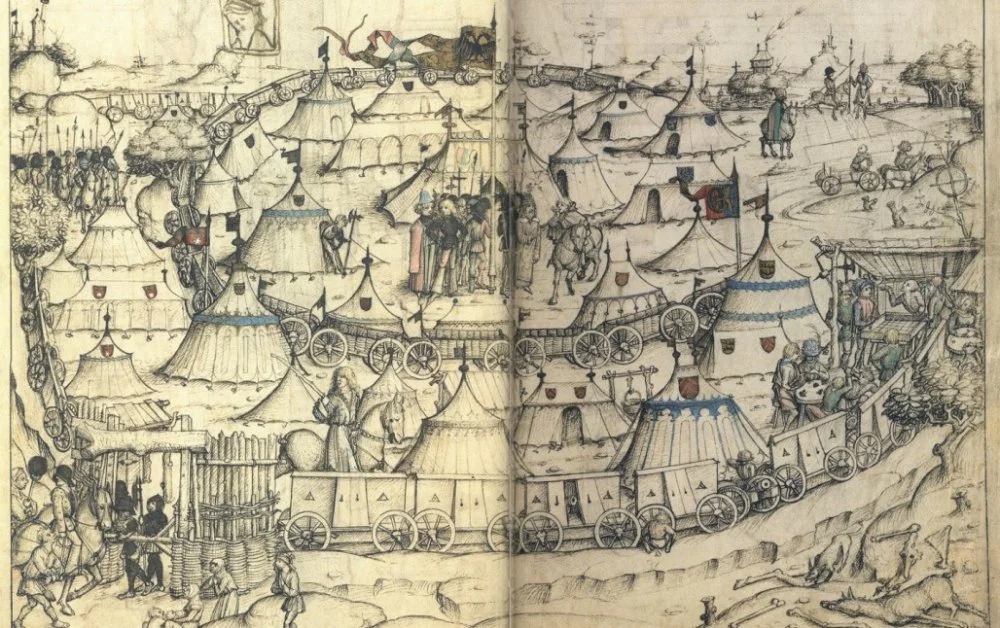

Medieval military camp / Wikimedia Commons

By the time Emperor Alexios I (1081–1118) ascended the throne, the Byzantine treasury was completely depleted, with no resources for the economic 'appeasement' of the Pechenegs. The only way out for Alexios I was to wage war to the end. In the summer of 1088, the emperor assembled a substantial military force and sent the Black Sea fleet to the Danube. The frightened Pechenegs sought peace, but Constantinople rejected their offer and arrested their envoys. However, in a land battle against the Pechenegs, Alexios I suffered defeat and barely escaped being captured. A massive ransom for Byzantine prisoners, paid by the victorious Alexios I, led to the unexpected rout of the Pechenegs. Before the major war, the Pechenegs sought assistance from the Polovtsians, who roamed the other side of the Danube.

Although we seem to have no chance of ascertaining even an approximate number of the Pechenegs in the Byzantine Balkans, their hordes, it seems, were quite numerous. In one instance, Anna Komnene mentions that the size of the Pecheneg horde was by no means 'ten thousand people' but expressed in vast numbers. The multitude of the Scythians is indirectly indicated by their significant presence within Byzantine society, leaving a vivid impression in the memory of contemporary Greeks as Byzantine authors created highly colorful and memorable portraits of the Scythians.

A Short-Lived Friendship

Initially, the Byzantines developed a kind of program aimed at appeasing the Pechenegs, and by concluding a peaceful treaty with the nomads, the Byzantines strengthened strategic fortresses along the Danube. South of the Danube in Paristría, a 'quarantine zone' was preserved—the absence of settlements and any sedentary infrastructure made it naturally unappealing to the nomadic hordes. Further, another significant and effective measure was implemented—granting the Pechenegs access to the goods they had raided from the sedentary population, such as crafted items and agriculture. The markets of Danubian cities were filled with coins, handicrafts, and agricultural products, and they attracted not only the Pechenegs but Russian merchants as well. The increase in trade led to an economic boom in the region, reflected well in archaeological evidence.

However, peace on the Danube border was soon disrupted. Around 1045, two Pecheneg uluses (consisting of around 20,000 people) led by Kegen, who rebelled against the Pecheneg khan Tirah, approached the Danube and sought Byzantine suzerainty. Emperor Constantine IX Monomachus received Kegen in Constantinople, honored him with the title of patrician,i

During the winter of 1046–47, Tirah's Pechenegs launched raids into Byzantine territory by crossing the frozen Danube. Kegen and the Byzantine forces managed to defeat the khan and capture him along with many of his followers. Gaining this victory was made easier by widespread diseases among the attacking Pechenegs, thought to have been associated with unfamiliar food and the excessive consumption of wine.

Nevertheless, the Pechenegs under Tirah soon revolted and returned to Paristría, joined by many of Kegen's followers. The excessive cunning of the Byzantines, who tried to use the hostility between Tirah and Kegen to control the Pechenegs more effectively, led to the opposite result. Chaos reigned in the eastern Balkans for several years to come, and the Pechenegs ravaged Thrace and Macedonia, defeating the Byzantine armies sent to fight them.

Portraits of the Pechenegs: Kegen and Tirakh

Among the Pechenegs, one of their leaders, John Kegen, was perhaps the most remarkable of them—at least as depicted by Byzantine historians John Skylitzes and John Zonaras. As mentioned earlier, he was the first of the Pechenegs to enter Byzantine subjugation, embrace Christianity, and be honored with the Byzantine title of 'Patrician' and position of 'Magister and Archon of the Pechenegs'. After achieving victory alongside the Byzantines over their enemy Tyrachus and capturing him, his nobles, and many Pechenegs as captives, he advised the emperor to execute all of them. However, this suggestion was regarded by the Byzantines as 'barbaric, impious, and unworthy of Roman mercy'. Contrary to Kegen's insistence, Tyrachus and other notable Pechenegs were not executed but recruited into imperial service instead. Kegen himself sold some as slaves and executed others among the captured prisoners, thus earning numerous blood enemies among his fellow tribesmen.

In 1051, the emperor sent Kegen to negotiate with hostile Pechenegs ravaging Byzantine lands. However, fortune had now turned against Kegen: as soon as he arrived among them, the Pechenegs killed him, breaking their oath, and tore his body into pieces. A Byzantine seal of Kegen has survived, depicting St. John the Baptist on the obverse with the saint's name inscribed and on the reverse bearing the inscription: ‘Lord, help John Kegen, Magister and Archon of the Pechenegs’.

Tyrachus, Kegen’s enemy, did not remain in the emperor's service for long. As early as 1049, when sent to the Balkans to quell hostile Pechenegs, Tyrachus defected to the enemy's side. In connection with the events of 1053, he was last mentioned by Byzantine historians as the leader of the hostile Pechenegs who inflicted a defeat on the Byzantines. Nevertheless, a seal of John Tyrachus from his time in Byzantine service has been preserved. On the obverse of the seal, St. Michael is depicted, and on the reverse, the name and title of the seal's owner are inscribed: ‘Lord, help Your servant, Patrician and Strategos John Tyrachus’.

Pechenegs kill Prince Svyatoslav. Miniature from the manuscript "Skylitzes of Madrid". 12th century / Alamy

The End of the Pecheneg Horde

The appeasement of the Pechenegs was facilitated by a new invasion from the steppes by their ancient enemies. During the winter of 1064, the Uzes, Turkic nomads, broke into Paristría and further into Thrace and Macedonia. The Greek name 'Uzes' seemingly conveyed the Turkic name 'Oghuz', and the Uzes mentioned in Byzantine sources belonged to the powerful Oghuz confederation in the tenth century, which roamed the southern Russian steppes and was well-known from Russian sources. They were called 'torqu', 'torchin', and 'torci' in Russian sources. In the mid-eleventh century, under pressure from the Polovtsians, some Oghuz tribes moved towards various Russian principalities and further west towards the Danube. Eventually, the Byzantines managed to sow discord among the Uzes by offering them gold. At the same time, a widespread disease struck the Uzes, caused by unfamiliar food and drink. The attacks of the Byzantine forces and their Pecheneg allies completed the devastation. The remaining Uzes fled beyond the Danube, and some of them switched sides to join the empire. The Uz leaders received elevated titles from the Byzantines. Pecheneg and Uz units, collectively referred to as ‘Scythians’, were incorporated into the Byzantine army as mercenaries, serving as light cavalry and mounted archers.

However, in the 1070s, due to financial constraints, the Byzantine authorities abolished annual subsidies to the cities along the Danube and gifts to the Pechenegs, unintentionally undermining the main pillars of their previous appeasement policy. Due to their troubles in Anatolia, the empire faced a severe budget deficit. It is possible that as part of budgetary measures, the Byzantine government aimed to minimize expenses and establish stricter fiscal control over the Danube markets. In response, the Danube cities and the Pechenegs revolted. The balance between the nomads and sedentary populations in the Balkans was lost, exacerbated by the Seljuks' capture of Anatolia and the subsequent collapse of the Byzantine administrative machinery there. The Pechenegs continued their raids on peaceful settlements and willingly acted as mercenaries, supporting both the rebels and the central authority, and chaos intensified in the Balkans with each passing year.

The only way out for Alexios I was to wage war to the end. In the summer of 1088, the emperor assembled a substantial military force and sent the Black Sea fleet to the Danube. The frightened Pechenegs sought peace, but Constantinople rejected their offer and arrested their envoys. However, in a land battle against the Pechenegs, Alexios I suffered defeat and barely escaped being captured. A massive ransom for Byzantine prisoners, paid by the victorious Alexios I, led to the unexpected rout of the Pechenegs. Before the major war, the Pechenegs sought assistance from the Polovtsians, who roamed the other side of the Danube.The Polovtsians came to help the Pechenegs, but their support came too late, and they demanded a share of the spoils. The Pechenegs refused to share and suffered a terrible massacre at the hands of their allies.

However, this did not stop the Pecheneg raids in the following years. A decisive battle between the Greeks and the Pechenegs took place on 29 April 1091 near Mount Levunium. Alexios I secured the support of Polovtsian warriors who arrived in great numbers at Levunium. The emperor feared a conspiracy between the Pechenegs and Polovtsians, but he had no choice but to proceed and engaged the Pechenegs in a major battle. Surprised to find themselves in a defensive position, the Pechenegs defended their own camp, enclosed by overturned wagons. The battle soon turned into a full-scale massacre of not only Pecheneg warriors but also their women and children, which lasted until the sunset of that day.

Alexios I Komnenos before Christ. Miniature. 12th century / Alamy

The Polovtsians and the Greeks took a vast number of prisoners and seized rich booty. There were too many Pecheneg captives to reliably guard, and the following night, a significant portion of them was butchered by the Greeks, contrary to the will of Alexios I, who regarded the act as inhumane. Some of the Polovtsians, shaken by the cruelty of the massacre, fled blindly beyond the Danube. Alexios I sent part of their loot after them.

Thus, the Pecheneg horde came to an end in April 1091. The refrain of a ditty composed by the Greeks to celebrate this victory sung: 'All because of just one day, the Scythians never saw May.' The surviving Pechenegs were resettled in Macedonia, and they served as light cavalry in Alexios I's army. After the victory over the Pechenegs, the Byzantines managed to fully restore their control over the Danube and Paristría.

The Role of the Pechenegs in the Byzantine Army and at Court

The Pechenegs served in the Byzantine army as light cavalry and mounted archers, referred to by the Greeks as 'Scythian troops' or 'Scythian allies'. When utilizing these Scythian troops (Pechenegs as well as Alans, Uzes, and Cumans), the Byzantines actively employed specific nomadic battle tactics, such as mass and unexpected attacks by mounted archers, luring the enemy into ambushes, et cetera.The common nomadic tactic of swift tactical retreat when met with resistance was vividly described by Michael Psellus, who wrote that the Pechenegs ‘... scatter in disorder and disperse in all directions: some throw themselves into the river, swim or drown in the whirlpools; others hide from pursuers and disappear into the dense forest; the rest come up with something else. After dispersing, they stealthily converge again from all sides, some from the mountains, some from the gorges, and others from the river.’ In addition, when facing heavily armored western European riders, the Byzantine Scythians aimed at the enemy's horses, as the Franks, once dismounted, became much more vulnerable.

Like many other civilized nations, the Greeks noticed the Pechenegs' particular inclination for plundering: after putting the enemy to flight, they immediately scattered across the territory, capturing prisoners and booty. In this regard, Anna Komnene has accurately remarked: ‘Such is the Scythian tribe: without defeating the enemy completely and consolidating the victory, they, giving in to plundering, squander the triumph.’ Interestingly, the Greeks did not hinder their Scythian allies in their plundering activities.

Mikhail Vrubel. Captive Pechenegs. Costume sketch for the opera "Rogneda" by A.N. Serov. 1896 / Alamy

The Pechenegs were also mentioned among the domestic slaves in the households of noble Byzantines. Michael V (1041–42) surrounded himself with Pecheneg youths, bought and castrated to become eunuchs. These Pechenegs were given high titles, and some of them served in the imperial bodyguard. There were also offspring from mixed Pecheneg–Greek marriages within Byzantine society.