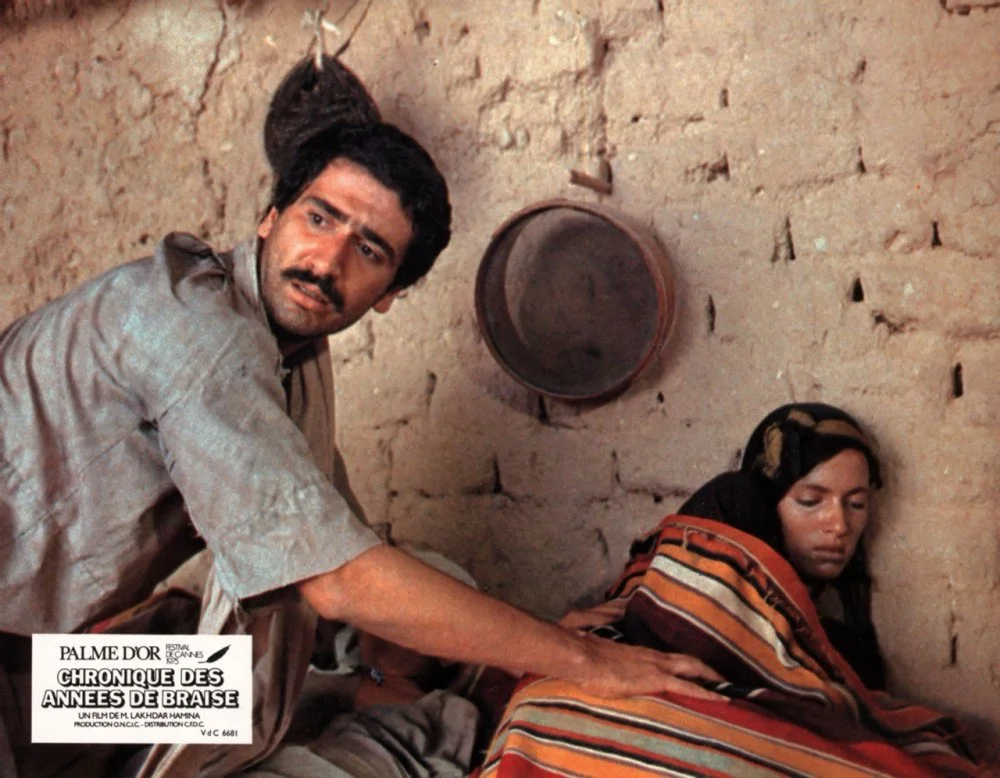

A shot from the film "Chronicle of the Years of Fire". 1975/Alamy

One girl once took two husbands at the same time, and they were brothers. She lived with them in the same house as in a harem. The younger brother didn’t know, but the older brother knew that she did it to punish him. She was a good, funny, beautiful girl. He just didn’t treat her as he should a wife, and so she decided to teach him a lesson.

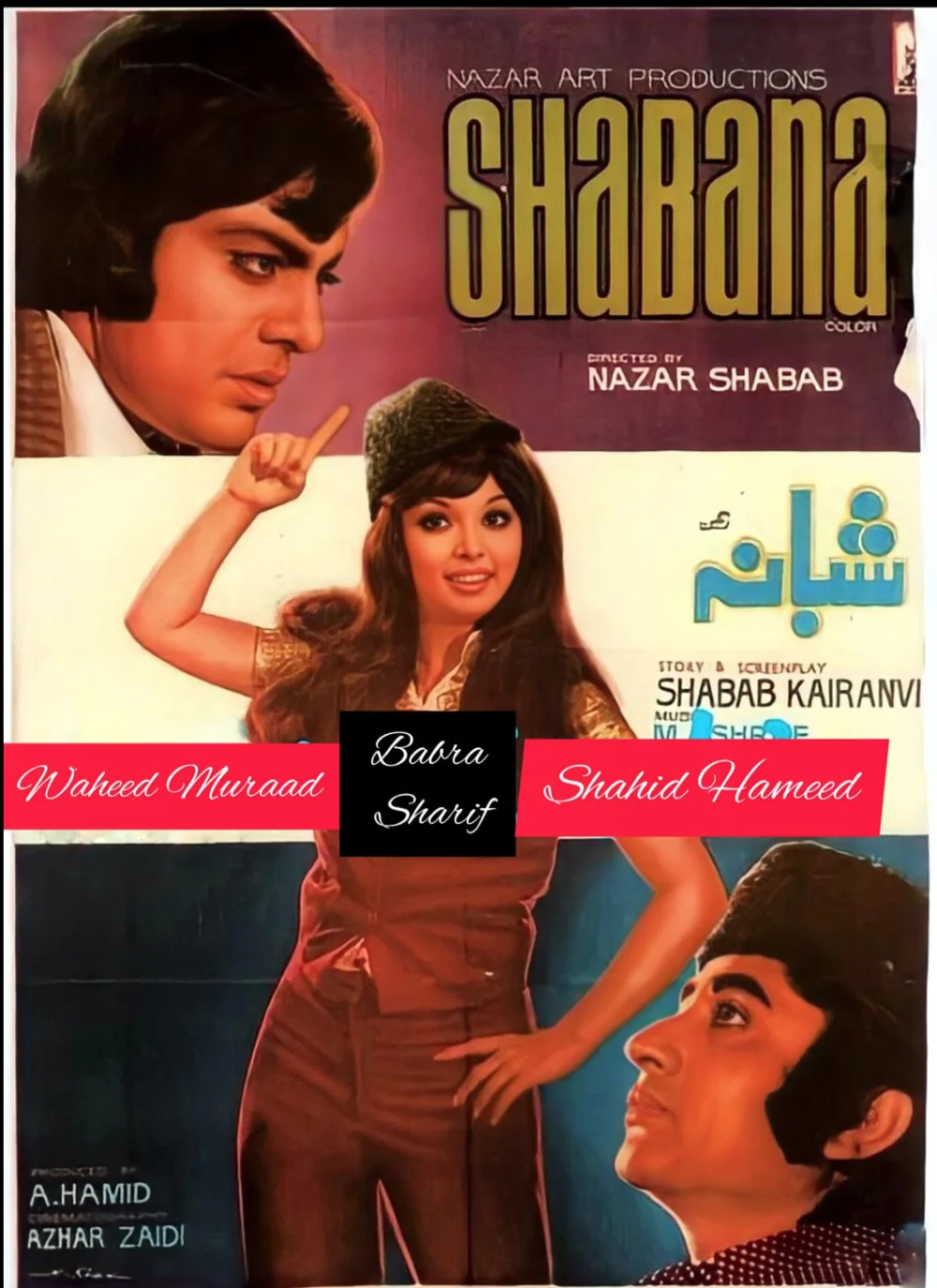

You would agree that such a story would raise questions, at the very least, in any culture. But the origins of this story are in the culture of Pakistan, an Islamic country where the laws of fiqh are sacredly honored. It is told in the film Shabana, which was released in November 1976 and ran continuously for four years, setting a record in the history of local film distribution. Thus, Shabana is neither a mishap nor an outing of the opposition—it was simply the darling of Pakistani audiences of the 1970s.

Shabana threw a hijab over her face only once in the whole movie, and that was also done for sheer effect, to lift it up and shock the older brother even more when the younger one proudly presents his beautiful wife to him. But she wore pants willingly, and in one scene, for fashion's sake—she was an avid fashionista and could cross the city in a fur stole, though it should be asked why the hell she would wear fur in the Lahore heat!—she even wore tails like in the movie Peter. And even when she didn’t wear men's clothes, she chose ones with masculine motifs on them, such as a lovely fitted dress with a sash pattern of rhinestone daisies, topped by a tightly buttoned men’s shirt with a lapel collar. Again, this was in keeping with the fashion of the time. She walked around the house striding widely, moving with the plasticity of that yard boy who is carefully avoided not only by all the girls, but even by other boys when he sticks out his hip, leans on the doorjamb, and whistles after them (the girls, that is). And when she danced with her younger brother in the open to the completely original funk masterpiece ‘Tere Siwa Duniya Mein Kuch Bhi Nahin’ (‘There’s Nothing in the World but You’) with its typical funk chorus, ‘zu-zu-zu-zu-zu-zu’, it did not look like a lovers’ dance but rather like the running and fiddling of two friends dazed by fresh air and freedom. Oh, and as a punishment, while her older brother was performing namaz, she would raid his stash of liquor and meet him already drunk.

The movie "Shabana". 1976/from open access

To complete the portrait of Shabana herself, let’s talk about the actress who played her. She started her career in 1973 with TV commercials for personal care products and is still revered as the Pakistani face of Lux soap. The skin on her face, which seems to consist of nothing but pleasant roundness, is something you would want to touch. In Shabana, her appearance might be compared to the Spanish diva Sara Montiel, but in movies of a different era, such as Alien (Shani, 1989), which we will discuss later, the German singer Sandra comes to mind. As befits a great model, she possesses the kind of mobile beauty that imitates the most desirable female type of the moment in terms of her hairstyle, makeup, and outfits. What counts, though, is the perfect foundation: skin, bone structure, proportions, facial expression. This actress adopted the pseudonym Babra Sharif. The etymology is clear: these were the first and last names of the two main characters in the most popular musical comedy of the time, Funny Girl. Shabana was just that, a musical comedy, and in it, Babra fully justified the name taken from the famous Jewish-American actress. Barbra Streisand was often accused of sometimes changing her characters’ hair so quickly that the length of the hair was illogically changed, if not within a scene then within a day. The same can be said about Shabana. If she is chatting with her sister in the morning with her hair cut to the line of her chin with tightly curled ends, in the evening she is following her first husband with a mane that reaches down to her buttocks and a separately tied, gangster-style ponytail.

But we won’t mess with your head any longer. You have, of course, noticed the presence of a sister. Of course, Shabana has a twin sister, the docile and proper secretary-stenographer Farzana. It was she who was secretly married, groomed, and then thrown out of the window of a mountain villa by the older brother, for whom Farzana worked. Crippled and pregnant, her misfortune bothered Shabana, who was a real troublemaker, who never left parties where everyone twitched as if overcome by a seizure and danced on the tables, or clubs where the gentlemen exchanged dialogues with her that went like this: ‘Coffee, tea, whiskey?’; ‘Whiskey, double and no ice’; ‘Oh, Shabana, you have good taste indeed!’ She even fought with the men, so she had to be dragged away by everyone and not the other way around.

The movie "Alien". 1989/from open access

So even though the plot of the comedy hides a twist—after all, we are not talking about a female bigamist—the character of the protagonist is actually like that. It was this character who allowed her to conceive and carry out her plan so flawlessly that the older brother was transformed, while the younger one, whom she really liked, started drinking.

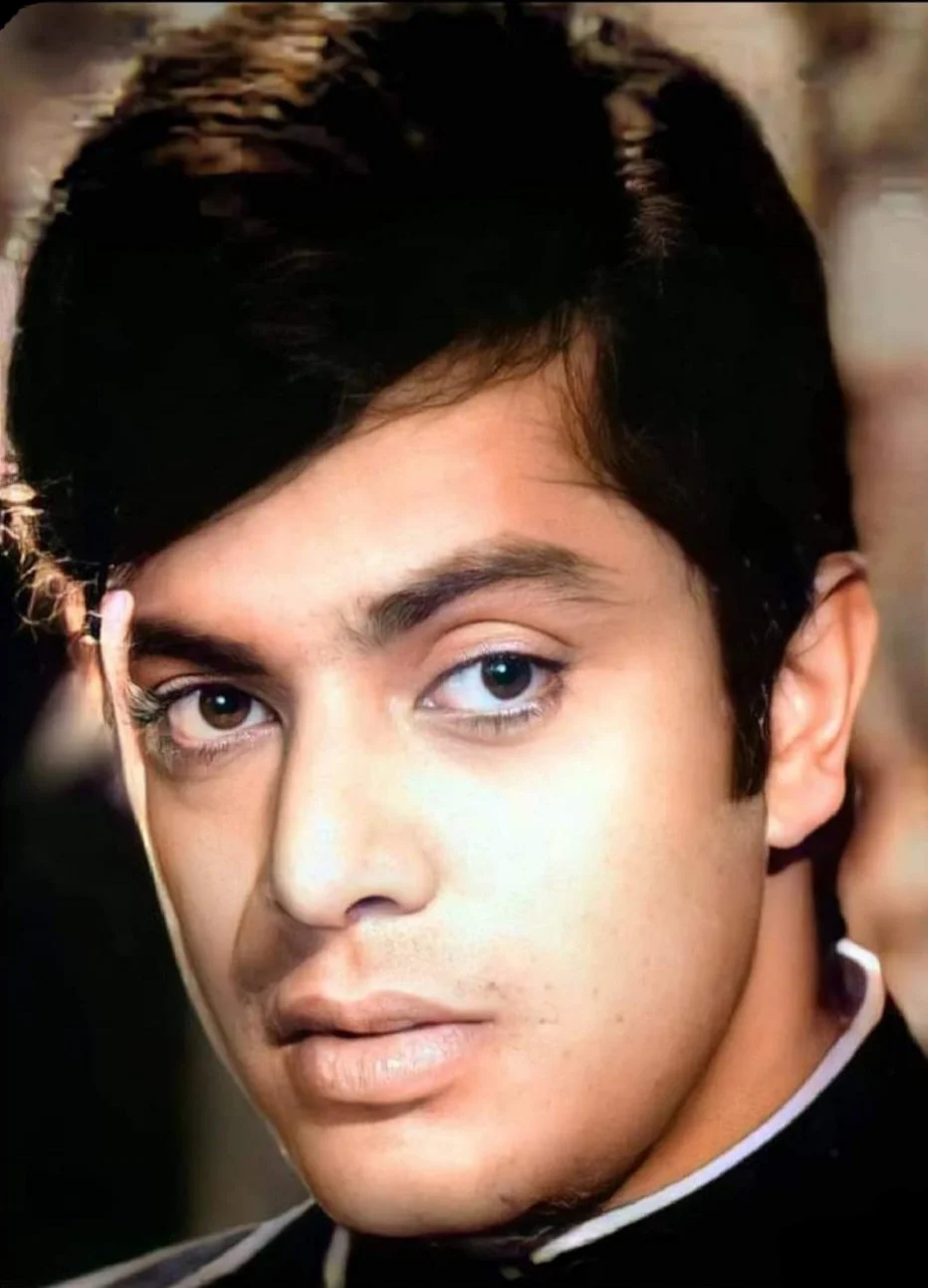

On later watching the film again, the scenes of the younger brother’s binge-drinking are particularly poignant. While Shabana was Babra Sharif’s first film role, it was also the swan song of perhaps the most important and certainly the most beautiful Pakistani film idol of that time, Waheed Murad. After the movie, the thirty-eight-year-old actor, struggling to survive the first sparks of the sunset of his masculinity, became addicted to a cocktail of alcohol and sleeping pills and crashed his car into a tree, disfiguring his face completely. He had huge, wide-set eyes, like the Mexican crooner Luis Miguel, and a similar freedom of movement, explosive, unpredictable, sprawling, and precise at the same time. When, in Shabana, his drunken hero slaps a column and then walks up a flight of stairs, you feel as if you are watching the chronicle of how this handsome intellectual walked away from the season of his own flowering (he turned to directing in 1969, using the symbolism of James Joyce’s Ulysses in his film The Hint (Ishara)).

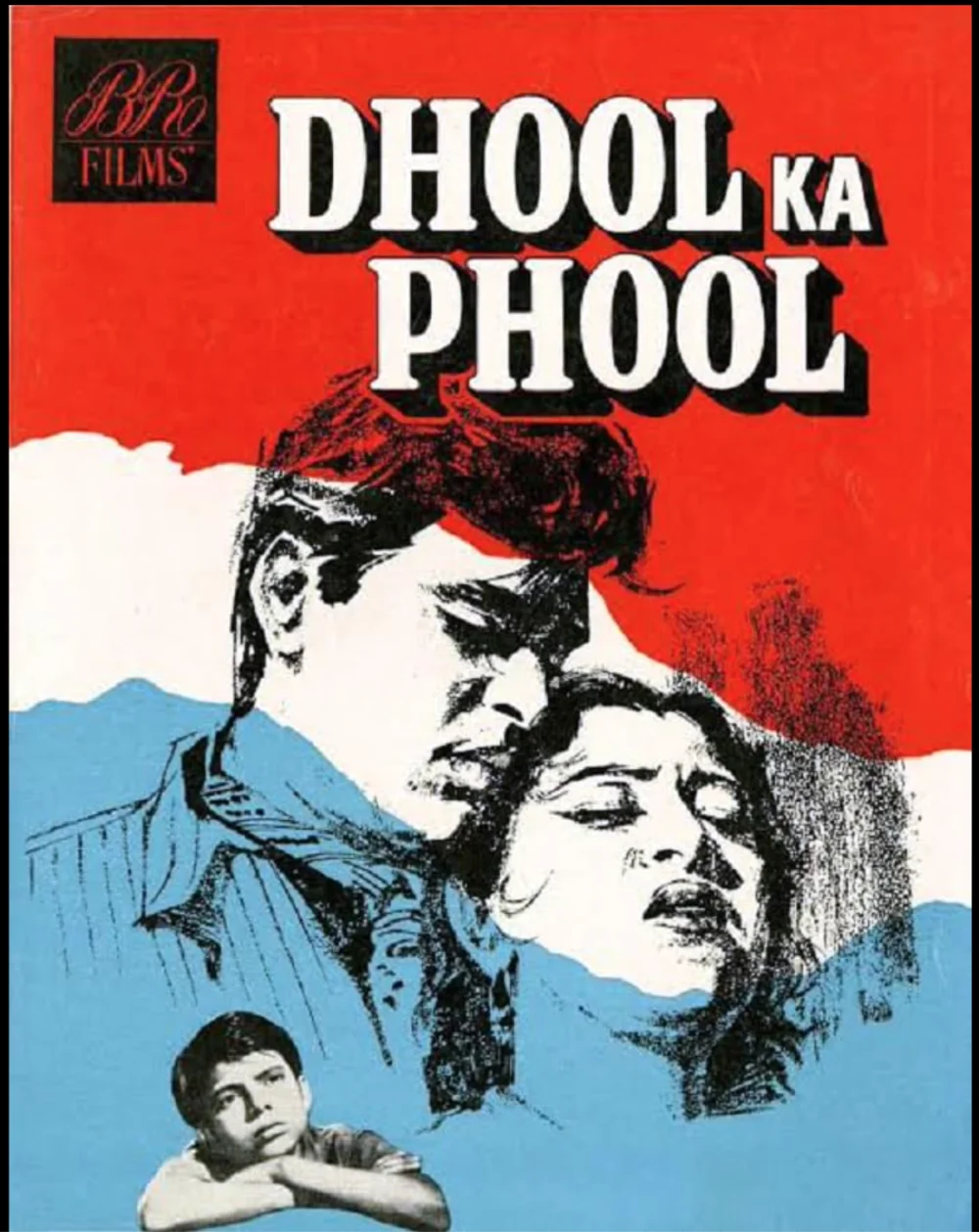

There are many other delightful details in the movie as well. For example, a servant who, when he drinks, immediately starts picking fights. This servant would easily make it into Kira Muratova’s work. It may seem that she is far away from Eastern cinematography, but that's not true. Her article on Rustam Khamdamov, for example, uses the title of the Indian melodrama Flower of Dust (Dhool Ka Phool, 1959). During the years of Soviet stagnation, she spent almost all her time at the Odessa Film Studio, waiting for a job in films, which she couldn't get for five or seven years. So she spent her time watching everything that was released in the Soviet Union at the time, and it is very interesting to find traces of obscure foreign films in her work (for example, the Swiss film Melancoly Baby starring Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg’s music in The Piano Tuner).

The movie "Dhool Ka Phool." 1959/from open access

Shabana was one of the movies screened in the Soviet Union. A scene in the movie shows Shabana sending the older brother a cup of extremely over-sweetened tea with a domestic worker, and the brother sends the servant saying, ‘Go and pour the tea on her head,’ to which the domestic worker replies, ‘How can I pour it there—she’s not a teapot! You go and pour it yourself!’ In Change of Fate (1987), Muratova turned this dialogue into an endless, as she liked it, monotonous verbal arabesque between two prison guards: ‘Go and pour the tea on his back!’, and the response ‘You go and pour it yourself!’

The cockiness of every verbal exchange in Shabana, the lyrical heroine who was invented as if to specifically turn Sharia law on its head, the characters’ careless handling of alcoholic drinks, the rhythmic songs and dances, and the general atmosphere of a kindergartener that flatly refuses to go to bed were the quintessential examples of the mad spirit that gripped Pakistani cinema in the 1970s. That spirit ruled the world in the 1970s, but as we have seen, each of the Eastern countries had its unique political conditions for it to prevail. In the 1960s, Pakistan was ruled by the military, but the last of them, Yahya Khan, was in no mood to stay in power forever and was unable to control the civil war in East Bengal, which led to its secession into the separate state of Bangladesh in December 1971. Immediately after that, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the leader of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), became president of the western part, what is Pakistan today, and first agreed with Indira Gandhi on the withdrawal of Indian troops from Pakistan’s borders. The threat of war—and Pakistan had been troubled by conflicts with its neighbor more than once—did not contribute to the fun. Land was taken away from the zamindars in favor of tenants, wages were raised, banks were nationalized, even the word ‘socialism’ was put to the test—the course set was liberal and good neighborly, and secular.

Waheed Murad/from open access

Melodrama is a genre of strict laws, and multiplied by Sharia law, they make the work of screenwriters almost meaningless, turning all movies into half a dozen chewed-up plots. Moreover, Pakistan is not India, and there are a few factors we should consider. Nature here is stunted, lovers cannot run among the pines, melodrama is confined to the pavilion, and even the architectural beauties of Lahore soon began to be overused. Because of the small population, big-budget movies are also a problem. The typical set-up is a frontal conversation between several characters. Traditional to the point of teeth-gnashing, all the motifs are melted into a single cauldron, all the pedals (unequal love, the condemnation of the poor bride by the relatives of the rich groom, the double suicide of the lovers, their daughter growing up in an atmosphere of hatred and ridicule) are pushed. Such was the tear-jerking melodrama Saiqa, the box-office hit of 1968 and the highest-grossing Pakistani film in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), where it was seen by 37.6 million viewers. A third of it consists of long episodes in which nine (!) people, arranged in a semicircle, usually around a tea table, have a conversation with the audience. It’s not as if this amusing counter-cinematographic technique was suddenly abandoned. For example, in The Dancer (Umrao Jaan Ada), released a week after the jaunty Sense in December 1972, there is still a scene in which seven people have the same conversation for three whole minutes about a gentleman shooting another gentleman.

Such a set-up is particularly amusing in the gothic vampire horror The Living Corpse (Zinda Laash, 1967). There, at a tea table, a respectable couple sits with their future brother-in-law, leisurely discussing his account of how, after searching for their missing son-in-law, he found him a vampire and stabbed him to death. ‘I still don't understand,’ the father says, scratching his chin. ‘You killed your own brother? But why was he already in the coffin?’ The mother meanwhile dangles her slippers under the table in the manner of a woman whose feet are stiff: the actress was simply not informed that the space under the table would also be in the shot.

The movie flopped in Pakistan. In fact, the plot is far from the logic of vampire legends: the professor was mixing an elixir of youth, but he overdid it and died, and then he rose from his coffin and started attacking everyone. It looks especially spectacular when his fangs close in on the neck of the bride/daughter, played by the superstar Deeba. In the final scene, the vampire, who is naturally afraid of light, is turned into a skeleton with an electric flashlight.

Babra Sharif/from open access

But in the West, the film has achieved cult status, and with good reason. A castle with cobwebs, a fireplace, a model of a cannon, paintings with images of bats and crows with the eyes of the man from Edvard Munch’s The Scream are the dream of the Hammer studiosi

The most conspicuous change in Pakistani cinema in 1972 was that it no longer wanted the audience to laugh at it but with it. Shabana was the culmination—but not the finale!—of this process, in part because the writers realized that silliness, complexity, and inventiveness should not only extend to the space within the frame but also to the technique of its actual cinematic presentation.

Even the opening credits are impressive. The surprising thing about them is that they are set against the backdrop of the everyday hustle and bustle of Lahore that Farzana passes on her way to work, while waiting for a bus, getting into an auto-rickshaw, and so on. Pakistani cinema avoids the city streets like the devil avoids church incense. It’s not that they’re completely unrepresentable, but it’s that they’re too ordinary. Pakistani cinema, unlike Indian cinema, is a priori anti-realistic. The viewer comes out of a dusty street that is in no way architecturally inspired and immediately falls face first into a cake of colorful decorative beauties, New Year tree garlands, and decorative rain that the filmmakers like to smear the screen in with almost childish abandon. That is why watching Pakistani movies of that time—where the heroes are completely cut off from the outside world and live in their own land of year-round festive trees, where everyone is idle from morning till night, where women, from schoolgirls to old ladies, twirl in front of the mirror and invent practical jokes, and where men read newspapers with an air of importance while hiding bottles behind them—represent a delicacy in the world of cinematography. Similarly, these movies keep their characters away from all mundane distractions. Housing bills, political news, and other nonsense don't reach here.

A shot from the movie "Embers"/Alamy

The makers of Shabana broke this rule: the audience seemed to enter the movie from the same street from which they entered the theater. And then the first miracle happened. Titles were replaced by the blink of an eyelid, and an eyelid with eyelashes. By the standards of 1976, this is not a bad trick for cinematography in principle. It was as if a projector was blinking for us. Although it was a familiar street, it was not our eyes that looked at it, but an invisible eye that flashed the names of the creators for us. Previous filmmakers immediately offered us a fairy tale. Here, too, the task was immediately declared: this is reality but one that is seen by a certain euphoric being who perceives life in a festive, fairy-tale way.

A strange vision appeared as an interlude between episodes. In fact, the filmmakers shot a close-up of a dandelion lamp and blew on it to make the LED tendrils sway. The dandelion lamp was a popular symbol of kitsch at that time—every Soviet schoolchild knew of it—but Pakistan was full of poor people, and in 1976 there were even more of them. They had never seen such a lamp, and God knows what they imagined it to be. In all likelihood, they perceived it as a captured abstract hallucination.

Multiscreen technology was used in the scenes featuring telephone conversations. And it got especially rowdy when the heroes sang the song ‘Tere Siwa’ to each other—the song was so good that it would have been a sin not to make two numbers: the first sung by Murad and the second by Sharif. In these scenes, double exposure was used for the first time in Pakistani cinema. Another trick was invented when the shots where Murad and Sharif, holding hands, were jumping around in a half-dried riverbed, wetting their bell-bottoms, were cut in half and then the parts where both performers were in the viewfinder were combined. This created the illusion that they were reflected in some kind of mirror.

These discoveries were immediately taken up and amplified. Pakistani cinema literally began to sparkle. For example, in the film Priceless Love (Anmol Mohabat, 1978), in a musical number filmed in the snow of the mountains, the cameraman amazingly managed to capture the shaky twilight of the winter light, for which double exposure was used again, emphasizing this vagueness, but in addition, the actress Shabnam appeared as if in a kaleidoscope tube, which was a favorite toy for children at the time. She was put in a close-up in the center of the frame, and around it, in hexagons, were six more images of her, smaller but exactly the same, fully duplicating the central one.

A shot from the film "Chronicle of the Years of Fire". 1975/Alamy

Art directors also let their hair down. In Fake Wife (Amber, 1978), Nadeem—a screen idol with the looks of Al Pacino, who combined the persona of lyrical hero and comedian, playing irresponsible, good-natured fantasists who get into trouble because of their detachment from reality—performed a beautiful waltz to ‘Tum Mere Ho’ (‘You Are Mine’), the beauty of which was emphasized by a percussion rhythm section typical of Eastern music. Whenever he began to play the tune at a party, he and the girl of his dreams would find themselves on an island at the foot of a three-meter-high candle, in the midst of water and darkness, with bare branches covered with festive lights.

Fake Wife deserves more time and discussion. If Shabana is an ordinary comedy, a challenge to everyday life, then Fake Wife is a comedy for the upcoming holidays, when there is no mood or energy to have fun because after this, it will surely come. It is decidedly impossible to recount all the vicissitudes that a dozen characters are involved in by the slacker Nadeem, who has lost an impressive part of his father’s fortune at the races in Lahore. Among those that seem unacceptable for the screen in a Muslim country is a scene of taking compromising erotic photos with a completely drunk girl, painted so clownishly that it’s a pleasure to watch. The appearance of the fat Tamanna is announced with the line ‘… and his wife is a stupid and belligerent woman.’ After this, a shot cuts to a scene in which Tamanna smashes a plate over the cook's head and begins to scream non-stop in her shrill voice.

All the points of intrigue come to a head when Nadeem brings a beautiful girl to his father’s estate and introduces her as the girl he secretly married in Lahore. Fascinated by her beauty—and under the influence of regular and impressive doses of alcohol—his father prepares the marital bedroom for them. But Nadeem and Mumtaz (the characters’ names are the same as the actors’) are not only not married, but also not even in love: the girl is doing him a favor for a favor. They lie on the marital bed and make a fuss—in one scene, Mumtaz crawls away from Nadim on all fours. The scenes are full of charm and nostalgia, and of course, the girl eventually realizes that she doesn’t want to do anything at all without this great playmate.

The movie "Under the Blue Sky". 1969/from open access

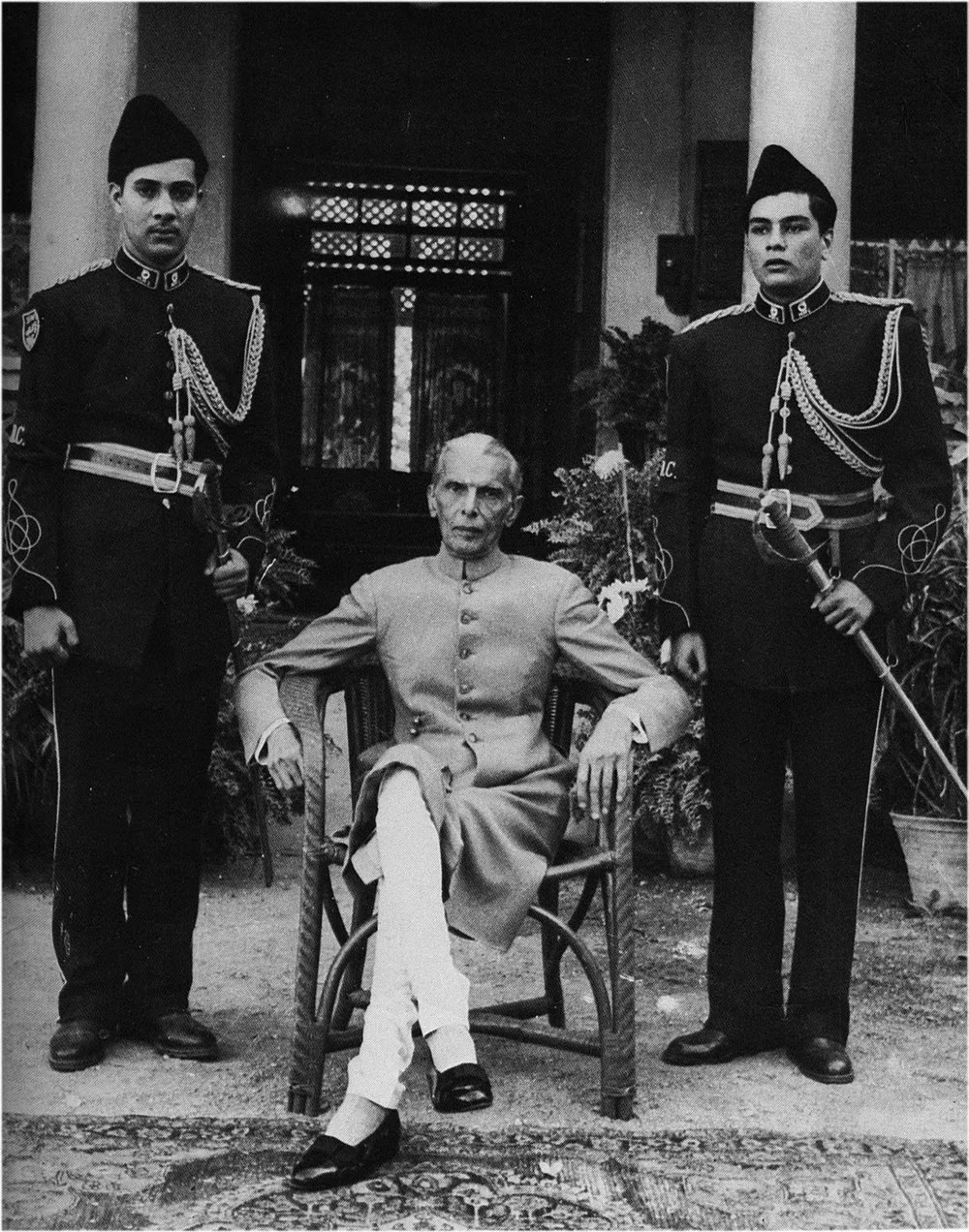

Fake Wife was released in early 1978. Six months before that, Pakistan had experienced a military coup that put General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq in charge of the country and set it on a course of Islamization. Heads flew, of course, but not those of the filmmakers. It was not like the Iranian Revolution. Those five years (1972–77) were just a holiday for the Pakistanis, a window into carelessness, while adherence to the precepts of Islam was something they were used to. The general simply screwed the nuts back on, tighter than they had been before they were loosened, and made sure that they would now stay in place forever. No one cared to remove the beloved films of the frivolous era from the screens, but the films written after the coup differed dramatically from the films of the previous period. The technical tricks were retained and even improved, but the mood? Ten months after Fake Wife, the same careless Nadeem sang a completely different song in Priceless Love: a spiritually uplifting song about a unifying impulse, about building for the good of the motherland, and the double exposure showed not another beauty, but photographs of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the main initiator of the partition of Pakistan from India, who is revered in the country as the Father of the Nation.

Interestingly, unlike Fake Wife, which became one of the year’s biggest box office successes, Priceless Love had very limited success. There are other similarities between the two films that highlight the differences that emerged in the country's cinematography over the course of the year. In Fake Wife, Nadeem spends part of the film in a hospital bed covered in bandages and a cast after a car accident. The doctor claims that only the girl he is delirious about can bring him back to life. When his father brings the girl to him and, in desperation, agrees to the marriage, Nadeem joyfully rips off the cast on his leg—it all turns out to be a sham, necessary for another of his divorces. In Priceless Love, Nadeem finds himself back in the hospital ward, again wrapped in bandages—these injuries caused when a horse he was riding bolted—but as the girl adjusts his blanket, she begins to scream in horror. Under the bandages, she—and we, the viewers, in close-up—finds a real bloody stump. The girl begins to bang her head against the door until her forehead is covered in blood.

Curiously, close-ups of freshly torn stumps and women banging their foreheads against something hard until their blood ran would become the main attraction of the cinema of the Zia-ul-Haq era. The highest grossing film of 1989—Zia-ul-Haq died six months before the film's release—would be Alien (Shani), with the same whole nine yards, though the stump would be a freshly severed arm, and the woman would be smashing her forehead against the bricks of the edge of a well. Her drops of blood fly picturesquely into the water by means of a cartoon trick, the most unpretentious in this movie that boasts many special effects. The film about an alien who takes the form of the dead fiancé of a girl from Earth (Babra Sharif) and gives her a son with superpowers is a reference to the American Starman (1984), but the sci-fi melodrama was thickly mixed with a film about dacoits, bandits who ravage villages, a genre known as Hindustani Western, the examples of which include the longest-running Mumbai film of all time, Embers (Sholay, 1975).

Politician and the founder of Pakistan Muhammad Ali Jinnah/Getty Images

The movie makes extensive use of computer graphics, which are dated and reminiscent of Tron, but still impressive in the low-income conditions of Pakistani cinema. The sight of a flying saucer, a kind of giant ball bearing with flashing lights on board, soaring over the rooftops of a Pakistani village, is a must-see for all followers of cinematic hallucinations.

It would be unfair in this discussion to ignore the cinema of East Bengal, which was part of the country until the end of 1971, especially since Under the Blue Sky (Neel Akasher Nichey, 1969) features the standard ‘woman with her forehead against the wall’ trick, which was introduced here long before West Pakistan became obsessed with it. A wealthy resident of Dhaka chases a taxi driver who is having an affair with his daughter out of his mansion. The daughter, trying to catch up with her lover, hits her forehead on an iron gate. A psychiatrist is called in, and it is curious to see what the work of a psychiatrist was like in Dhaka in the late 1960s.

Trishna sits in her bed, dazed, with a man sitting next to her, whose unimaginable hair would drive you crazy. With his eyes wide open under his thick glasses and wearing a manic smile, he tells her, ‘Look to your right. Do you recognize who that is?’ In a colorless voice, she replies ‘Trishna,’ echoing the way in which the madwoman named Lucía in Almodóvar's Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown would pronounce her name. In the end, all the psychiatrist manages to achieve is for Trishna to bang her forehead again, this time against a tree.

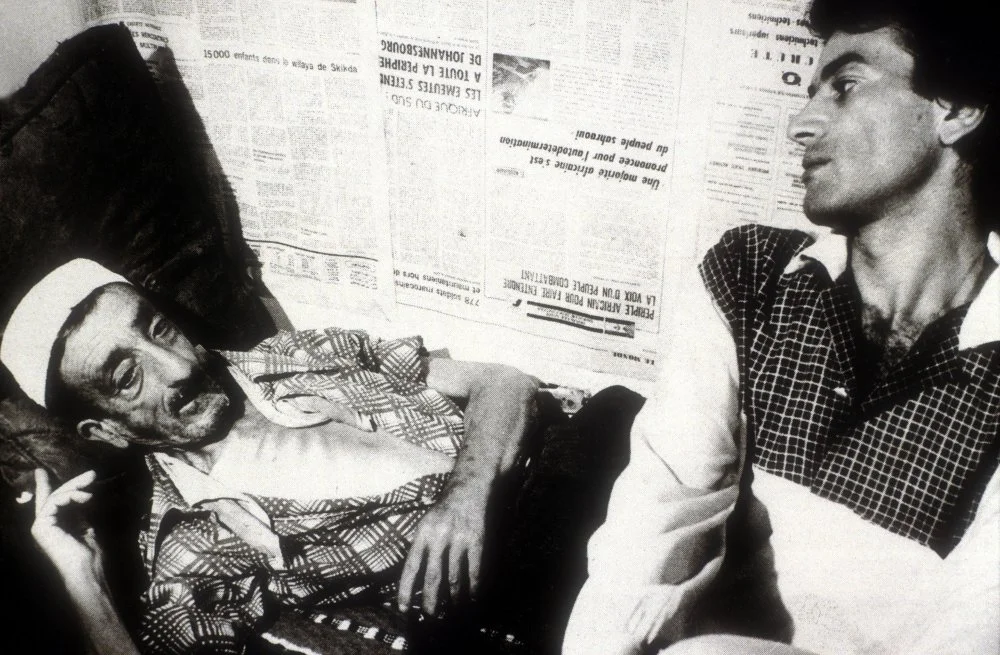

A shot from the movie "Shy Omar". 1976/Alamy

What is important is the radical difference between the cinema of East Pakistan and West Pakistan, which would define the distinctive image of the cinema of the future Bangladesh. The films of Pakistan are isolated from the city, but this one is immersed in it. The taxi driver’s profession allows the protagonist to show us the hustle and bustle of the railway station and the huge white building nearby. We also see the layout of Dhaka, where you have to drive for a long time through wasteland before you reach the street: an oasis of fenced-in plots and dilapidated apartment buildings where people like him live. This is the world of those who have seen the magical movies we’ve been talking about in this series: young boys who spend all their time playing and talking to each other, infected by the dreams of songs and movies, who know no girls except their own sisters. I suppose the pretty girls we’ve listed are as much an attraction to them as a living dinosaur would be to us. They’ve been taught the dream, they know it’s real, but they can’t touch it or even see it.

The best film about such boys in the period we are describing was made in Algeria in 1976. The film is called Shy Omar (Omar Gatlato), and its director, Merzak Allouache, would go on to win every major international film festival prize. His 2003 comedy about a Maghrebian transvestite in Paris, Chouchou, would cause an explosion at the French box office, catapult Gad Elmaleh to superstardom, and put the Canadian singer Diane Tell of the early 1980s back on the map. But for now, he lives and shoots in Algeria, a socialist upstart where cinema is entirely subsidized by the state and has so far focused only on the recent past of the national liberation movement. The sum of these developments led to the three-hour widescreen epic Chronicle of the Years of Fire (Ahdat Sanawovach El-Djamr, 1975), directed by Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, which won the Palme d'Or at Cannes the same year. After such a huge cinematic hit, Allouache was the first to realize that it was time to take a look at the street of today. This is the same Eastern street that the movies discussed in our article used to overlook.

‘When an Indian film is released in Algeria, you don’t need advertising,’ says Omar, the protagonist (played by Boualem Benani) of Shy Omar. Through the movie, he is in conversation with the viewer, explaining the place and his own life, often looking directly into the lens from the crowd of friends that surrounds him. The film is accompanied by a simple and beautifully composed melody, tender and masculine. The mood changes with the arrangement—from a brooding guitar strumming like cigarette smoke to weightless female vocals.

Four years later, Shy Omar had a curious, and indeed poignant, sequel in Brahim Tsaki’s Children of the Wind (Aulad el rih, 1980). There, the protagonist is a boy. At home, he has only a drunken and old father. The boy boils eggs and sells them to regulars on the terraces. Day after day, his eyes are drawn to the most popular actor in Algeria, Boualem Benani, whom the boy had seen in Shy Omar. He longs to go up to him, to talk to the actor who, in that film, said something so tender and important about him and their lives that the child might see him as an older brother. But he doesn't even dare to offer him his goods. If the hero of his dreams simply tossed him a coin, how hurtful that would be! If he turned out to be like Omar, rubbing his head, talking to him about the things he understands, spending time with him, it would only be worse. The boy’s fear is not that Benani/Omar won't be able to give him what he needs. He is afraid that he will be given what he needs and then deprived of it, just as the Eastern films he knows well give their confused, insecure viewers the most important thing they need—happiness—and then simply take it away.