Wikimedia Commons

The legend of Nasreddin Hodja, retold by Leonid Solovyov, is one of the bridges that connected European and Asian traditions in the Soviet people.

Stories of Nasreddin Hodja, the legendary trickster, span Eurasia—from China to the Balkans—blending humor, wisdom, and sharp social critique. In the Soviet era, Leonid Solovyov’s The Tale of Nasreddin Hodja introduced this beloved folk hero to a new generation of readers, showcasing Central Asian culture while subtly challenging authority. Still widely popular years after being published, the enduring appeal of Nasreddin Hodja’s adventures proves that laughter, wit, and the fight against injustice are truly universal.

Nasreddin Hodja is always easy to spot—wherever he goes, his trusty donkey and sharp wit are never far behind. But beyond these, everything else about him is as changeable as the water in an irrigation ditch, shifting roles and identities with ease. One moment, he’s a wandering philosopher; the next, a mischievous rogue, pausing by the roadside to nibble on flatbread, savor an apricot, and count the meagre tanga in his worn purse.

The trickster—a rogue, a deceiver, a scoundrel—is, along with the hero, the villain and the victim of fate, one of the oldest archetypes of the human cultural consciousness. Indeed, the illustrious tribe of tricksters includes figures as diverse as Hermes and Odysseus, Sun Wukong and Zhu Bajie, Anansi and Till Eulenspiegel, Lisa Patrikeyevna and Reynard the Fox, Wile E. Coyote and Raven, Loki and Set. The trickster is the master of deception, the one who palms the cards, twists the layers of reality, and turns the sublime into the ridiculous, the great into the trivial. He introduces chaos into order and turns the tragedy of existence into comedy, revealing the humor hidden in the human condition.

Nasreddin Hodja became the trickster for all of the East, with anecdotes about him circulating from China to the Balkans, reshaped by every culture that embraced him. The vastness of this territory gave Hodja two completely incompatible and seemingly paradoxical features—he is instantly recognizable, yet impossible to define.

Wife asks Nasreddin:

- If we had money and decided to make pilaf, what would we need to buy?

- One measure of rice and two measures of oil.

- Two measures of oil for one measure of rice only?” exclaimed the wife in surprise.

- If we are going to imagine making pilaf, then let it at least be a fatty one!

He is young and he is old and he is a middle-aged man. He is wise and he is foolish. He is greedy and stingy and he is generous and noble. He has a beautiful wife, resembling a houri on one hand, and he is married to a loud and ugly fool on the other. He is a mullah and an atheist, a merchant and a beggar, a potter, a blacksmith, a weaver, and an advisor to a ruler. Even his name is changeable - Hodja, Molla, Kozhanasyr, Afandi...

And yet we always recognize him because behind his malevolent donkey always follows laughter. This is the laughter that allows us to lift our heads up and straighten our shoulders; the laughter that saves no one and respects not a sacred thing.

Hodja's homeland is claimed by about thirty countries and disputes about how real his prototype is have been going on for hundreds of years. Some popular anecdotes about him suggest that if his prototype did exist then he would have lived in the 14th century, which is also supported by the image of Tamerlane (Timur) that often appears in these anecdotes and against whom the cunning man stood.

Bust of Tamerlane. 1941/Wikimedia Commons

In any case, it is known for sure that the first written surviving mentions of Hodja Nasreddin are dated to the end of the 15th century in a composite description of the life of another folk hero, the warrior dervish Sari Saltuk Dede, compiled by the Turkish author Abu al-Khair Rumi.

Soviet Hodja

Of course, the anecdotes about Hodja Nasreddin were created and tested by people according to the same principle by which the anecdotes about Chapaev or the naughty boy Vovochka were told with no concern for matching the image. People would simply insert a familiar name into any funny situation. The eclecticism of such a hero is inevitable, but some features that are being passed from one story to another are always inherent to him. Vovochka is rude and cynical, Petka is naive, whereas Hodja thumbs his nose at the powerful of this world.

One time Timur saw Hodja telling something to the courtiers:

- Hey, what are you lying about there?- shouted the Khan.

- What can I do, Your Highness,- replied Hodja, - I have to lie because I was just telling these esteemed people about your justice and wisdom.

It was precisely this feature that was developed in the great, yes, indeed great books by a man who gave Hodja Nasreddin to all children and adults who lived in the Soviet Union. The incredible in its coverage circulation of his duology about Hodja The Disturber of Peace and The Enchanted Prince, eventually united in a single Tale of Hodja Nasreddin, did an amazing thing: they turned Central Asia into something close and familiar to a great number of schoolchildren in Moscow, Kiev, Tallinn, or Chisinau. Although adults were amazed by the incredibly colorful, vivid, and lively tale, they no longer knew how to incorporate it into their world. However, for the children of Hodja, it was simply a fantasy world to immerse themselves in, for those who could read, of course. All the turbans, caravanserais, old men, and Baghdad thieves gave a child raised in the European tradition the key to the gates of Asia.

Leonid Solovyov. The tale of Khoja Nasreddin. 1957

Interestingly, Soloviev's Hodja is not a children's book at all, and it is a cultural and pedagogical mystery why it was published by Detgiz Publishing House from the very beginning in the rather puritanical USSR, and why it is still included in the list of one hundred mandatory books for extracurricular reading in high schools for the students in Russia. The horrific scenes of torture and impalement on stakes are bad enough, but there are also overly erotic and indecent scenes in that book - more than enough. Let us remember the knives of palace physicians who turn men into eunuchs, or the naked lover of the beautiful Arzi-Bibi sitting in a chest, or the beautiful almost exposed female dancers on the drums... The author of this text once almost drove his parents crazy at the age of seven, insisting in the presence of some guests on showing him "the bed on which I was conceived." The process of conceiving was not even vaguely understood by the author at that time, but the phrase from the book "Cursed be the bed on which I conceived you!" apparently deeply intrigued the child's imagination.

Another childhood memory: my parents entertain their guests again. I am together with my relatives, a few boys and girls, in the children's room, and we are playing Bridge of Fortune Tellers from Hodja. We wrapped towels into turbans over our heads and put on our grandmothers' robes... We also still needed a human skull for fortune telling — so we had to remove poor Doll Nadya’s head. However, with some effort, we could always put the head back on the neck peg.

Solovyov placed his Nasreddin in Uzbekistan: Bukhara, Fergana, Kokand — all these names lured us no less than the Caribbean and Jamaica. It's hard to say now what percentage of Soviet schoolchildren had a period of deep infatuation with Central Asia thanks to Solovyov's book, but it was definitely huge. Simultaneously, Hodja delivered another powerful message to its readers, which was somehow missed by Soviet censors. This book truly taught to hate and despise the authorities.

Disturber of the Peace

In Solovyov's book, the khans, emirs, their courtiers, judges, customs officials, guards — all of them are described as greedy, repulsive sadists, liars, and hypocrites drunk on impunity. They are sociopaths who revel in executions and the suffering of others. Meanwhile, the bloodiest scenes such as stakes with people writhing on them, prisoners beaten to death with whips in dungeons were described by the author in a completely different way than fans of such medieval horror stories such as Druon, Aleksey Tolstoy, or even George Martin. There is no hidden relishing of tragedy, no sadistic secret eroticism, not even a desire to shock and awe the reader.

We see everything happening through the eyes of Nasreddin, with anger, sadness, completely bewildered at why people do such things to each other?

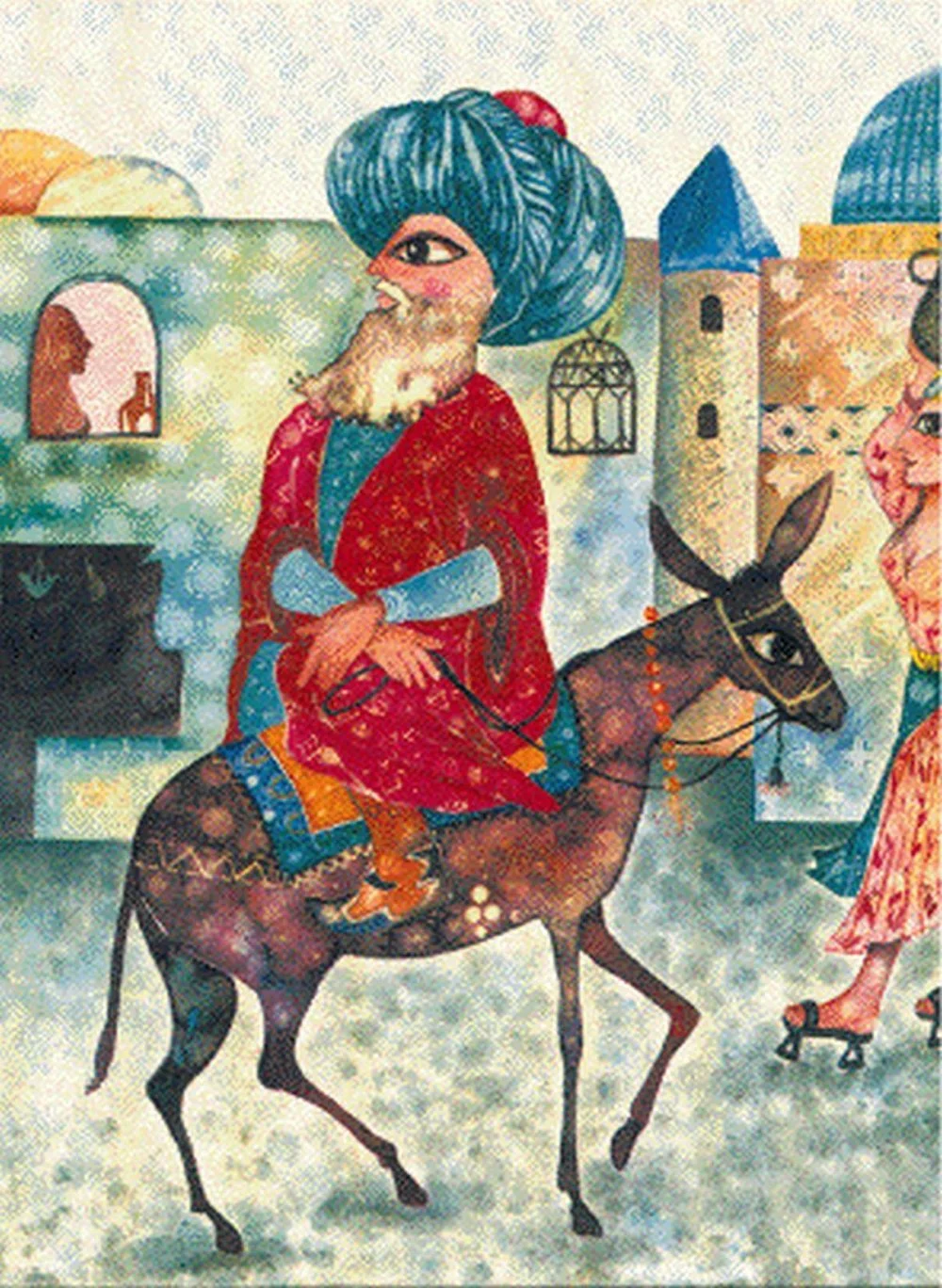

Miniature of Khoja Nasreddin. 18th century/Alamy

And we answer this question together with Hodja: the worst always come to power where there is no strong societal control. The greediest come to power and the most cowardly, and the cruellest. Solovyov's selection process for officials and courtiers is based on the fact that the scoundrels can quickly eat up their competitors, the thieves can steal enough money for bribes and gifts, and the flattering liars can pave their ways with deceit, thus quickly rising to the top.

Thieves as guards, unjust judges, and sadistic prison wardens, and at the very top, something completely cruel and paranoid, such is the power structure in The Tale. And this power is only willing to shape the life of the ordinary people into the most abhorrent prison.

"We believe that they no longer fell onto the millstone of that glorious mill where the waters of selfishness turn the wheels of cunning, where the shafts of ambition set the cogs of denunciations in motion, and where the grindstones of envy grind the grains of lies."

"New prohibitions with new threats were constantly announced; just the other day a decree was issued about adultery, according to which unfaithful wives were subject to punishment by whip, and men were subject to a castration by doctors' knives. There were many other decrees like this one. Every resident of Kokand lived as if in the middle of an interlacing of thousands of threads with suspended bells: no matter how careful you were, you would still touch some thread and a quiet ominous ring would sound, fraught with many troubles."

Yes, of course, in post-revolutionary USSR such an attitude towards any authority other than towards a socialist-communist one was highly welcomed: kings, presidents and their minions were supposed to be painted in the darkest colors, but at the same time it was necessary to show that such a state of affairs was abnormal and temporary, that the people would always resist and evil would be punished...

Timur and Hodja went to the bathhouse together, and Timur was wearing an expensive bathrobe.

-Hey, Hodja, -Timur asked, - they say every person has their own price, how much do you think I'm worth?

- Ten tumans, - Hodja replied.

- Have you gone mad, dog?! This bathrobe alone costs that much!

- That's precisely why I valued you so highly, Your Highness,- replied Hodja."

But in Hodja, there is no punishment of the authorities by the people: they drown the moneylender Jafar and throw the greedy Agabek into prison. But those were only rich people, not government officials, and the government itself punished them. All emirs, shahs, and dignitaries are completely safe: woodcutters do not come to save Little Red Riding Hood, the Snow White dies in her coffin, there will be no retribution for high-ranking villains, this is not a fairy tale — this is life.

The people in The Tale is both cautious and unfree; people accept evil as a given, they choose the as-if-nothing-happened approach and do not want to know the truth. If there were some hints of people’s wrath and fears of such wrath on the side of the Bukharan authorities in the first part of the tale, the second part of the book, written several years later, completely abandons these illusions.

Timur Bekmambetov. The performance "Khoja Nasreddin". Theatre of Nations, Moscow. 2020

"Meanwhile, all this prosperity that he so cherished was just a small teahouse hastily built from clay and reeds by hands, costing no more than two hundred tangas even for the most generous buyer; Safar had nothing else, no house, no garden, no field, but he trembled as if he kept gold ingots in his cellar. This poor man possessed another priceless treasure - his freedom, however he did not know how to use it; he kept himself on a leash, he himself bound the wings of his soul!"

The book, formally created along the lines of agit-prop (soviet propaganda), concealed a huge fig between its pages (Note: to show a fig — a vulgar gesture made by sticking the thumb between two fingers): it exposed any totalitarian power. We can only recall one similar work created by Schwarz around the same time called The Dragon. Many Soviet censors were intelligent people who could read between the lines. The Dragon written in 1942, was banned from any production, staging and publication in 1944, but at least Schwarz himself was not touched.

With Leonid Solovyev, everything was much sadder.

A Masterpiece from Behind Bars

Born in 1906 in Tripoli in the Ottoman Empire to parents who were officials of the Russian imperial Orthodox Palestinian society, Leonid Solovyov spent his youth in Kokand, writing for Tashkent newspapers. At the age of twenty-four, he arrived in Moscow to study at the literary and screenwriting department of the Institute of Cinematography. He published several fairly weak stories and short stories, as well as a completely falsified work under the name of Lenin in the Creative Work of the Peoples of the East, in which he composed all the folk songs about the great leader. Then in 1940, he wrote the first volume of Hodja, Disturber of Peace, which caused delight among the reading public. However, due to the start of the Second World War, he had to postpone writing a sequel. Solovyov started working as a war correspondent, mainly writing sketches about the lives of sailors and soldiers.

In 1946, he was arrested, and it wasn’t because of his book—it was for ‘terrorist activities’ instead. Along with many other journalists, he was accused of plotting to kill Stalin, which was, of course, utter nonsense, the usual fabrications habitually cooked up in those times. Nevertheless, the writer got sentenced to a prison confinement of ten years for nothing, and the same imprisonment was awarded to his colleagues, against none of whom could the authorities come up with an even half credible accusation.

It was at the Dubravlag camp in Mordovia, where he worked as a guard at a local production facility, that he wrote The Enchanted Prince, his second part of the duology. The camp commandant was kind to the writer, as he had enjoyed the movie adaptation of the first book, and he allowed Solovyov to write and even preserved his manuscript until his release.

Solovyov was released in 1954, during one of the first waves of rehabilitations. He returned to freedom as a poor, seriously ill, and toothless man, but he managed to see the publication of his book in 1956 and witness its tremendous success. Indeed, his own suffering mirrored the struggles he depicted in his work, making his writing all the more poignant and authentic:

And when he woke up and his eyes grew accustomed to the darkness of the prison, he saw around him a multitude of different criminals. Each of them was a step on that terrible staircase by which the nobleman made his brilliant ascent to the heights of power, wealth, and honor … but there were other steps too, very treacherous ones for the climber, on which it is easy to break a leg, or unintentionally, even the neck—this is what the tireless noble builder forgot! Anger and pity choked Nasreddin Hodja; even he, who had seen so much, did not think that such a terrible, such a disgusting place was anywhere possible on earth; as if he had descended into the very abode of evil! Another scar was added to his heart, one of those that armor the heart with the cruelty of mercilessness.

Leonid Solovyov was a semi-paralyzed and tortured fifty-five-year-old when he died in 1962 of yet another hypertensive crisis.

Timur Bekmambetov. Animated film by "Bazelevs" studio about Khoja Nasreddin/Provided by "Bazelevs" studio

The Victorious Hodja

How is it then that a book written mostly in one of the worst places a person could end up, a book that often tells of quite monstrous events, ended up being remembered as a lighthearted adventure, a hymn of joy, even a cheerful staple of children’s literature? Was it because the blood and pain in it passed through the purifying flame of irony? Was it because Hodja would still fool everyone and emerge victorious? Yet, let us consider another famous trickster tale, the one about Till Eulenspiegel, a famous German rogue from the Middle Ages. That story too is filled with humor, jokes, and clever antics, but no one would ever call it cheerful. What makes The Tale of Nasreddin Hodja different?

One suspects that the feeling of joy and thrilling adventure in this work is the stamp of the author, who did not merely write a dramatic narrative. In this book, we see his great love for the world he depicts—for the world of his youth; for that nostalgic feeling of happiness and freedom, which his memories of the cities of Central Asia brought, the people he knew there, the apricots he ate, and the fairy tales that he had heard. It’s no wonder that the heart of the book is an unexpected insert about the childhood of Nasreddin—the brightest and most vivid part of the diptych, a picture of an ideal world where true evil is only gathering strength but does not yet dare to cast its shadow on the shaven head of a young Bukharan boy.

In magical Bukhara, under an incredibly blue sky, where birds, cats, and snakes are friends with the child, where an all-forgiving mother waits with a jug of fresh milk, where donkeys have velvety noses, and old, ugly gypsy women turn out to be kind and grateful, and where you have the power to give kindness to everyone who needs it. This feeling of childish omnipotence, when ‘everything will be according to my will’ and there is no real fear because you are sure of your immortality, is also preserved in the adult hero. He is merciful, as only good children can be, but he is also merciless, like them, when he deceives and steals from the scoundrels. According to Orkhan Jamal, founder of the Muslim Union of Journalists of Russia,

‘This is a description of what is happening inside Islam, inside the Islamic ummah, with love … with genuine, honest, and sincere love, with genuine and honest solidarity.’

It is no wonder that the people of Asia consider The Tale of Nasreddin Hodja an anthem of their own: it contains nothing of souvenir forgery, imperial condescension, nothing that irritates so much when you read books about your culture written by someone who is distant from it. Published at a time when official culture was still weighed down by dogma, Solovyov’s novel offered something radical: a celebration of individual cunning over oppressive power, of laughter as a form of resistance, and of a world that, despite tyranny, could still outwit its rulers.

Mausoleum of Khoja Nasreddin/Alamy