North Korea emerged triumphant from the era of Stalinism. In fact, for several decades, the country established and sustained a society in which state control over the economy, culture, and citizens' daily lives reached a level almost unparalleled in history. However, this society proved short-lived and began to disintegrate after just thirty to thirty-five years. Andrei Lankov, a renowned expert in East Asian and Korean studies, delves into the evolution of North Korea from its ancient origins to the present day.

From 1948, Kim Il Sung persistently sought Moscow's approval for a military operation against the South. However, until January 1950, these demands were made unsuccessfully. Joseph Stalin considered a war in Korea neither desirable nor acceptable, fearing it could quickly escalate into a third World War, given the United States' nuclear capabilities. Stalin had no desire to engage in a conflict with the US, which, at the time, had a monopoly on nuclear weapons, especially compared to the ambitions of a small communist regime in East Asia.

A Dashing Opening

Nevertheless, by the end of 1949, several events occurred that changed Stalin's stance on Pyongyang's requests. First, in August 1949, the Soviet Union conducted its first nuclear weapons test, creating a deterrent that reduced the chances of the Korean conflict escalating into a global war. Second, on 1 October 1949, the People's Republic of China was proclaimed. Despite the less-than-ideal relations between Stalin and Mao, the victory of the Chinese communists shifted the balance of power in East Asia in favor of the socialist bloc. Third, by that time, Soviet intelligence had acquired several documents—and it is known that Stalin was familiar with these—that confirmed that the United States did not categorize South Korea as a country they would automatically defend in case of conflict. Secretary of State Dean Acheson publicly articulated this position in January 1950, significantly reducing the likelihood of American intervention in the event of a North Korean attack on the South.

Chinese postmark. Stalin and Mao shake hands. 1950 / Wikimedia Commons

In this context, in January 1950, Stalin finally agreed to yet another request from Kim Il Sung seeking permission for a military operation. However, during negotiations in Moscow with Kim Il Sung and Pak Hon-yong in April 1950, which were focused on preparing for the military operation, Stalin issued a warning: if the United States intervened in the conflict, the Soviet Union would not send ground troops to the Korean Peninsula (although air support had already been promised). In response, Kim Il Sung and Pak Hon-yong assured Stalin there would be no need for such assistance. They claimed that the population of South Korea awaited the arrival of North Korean troops, who would be welcomed as liberators. Additionally, it was claimed that up to 100,000 partisans were operating in the mountains, and after North Korean forces crossed the border, they would immediately descend and seize control over a significant part of the country.

It is unknown to what extent North Korean leaders believed these assurances themselves. However, the Soviet Union had no way to verify these claims as there was no Soviet intelligence network in the South at that time. They had to rely partly on the optimistic accounts of Korean communists.

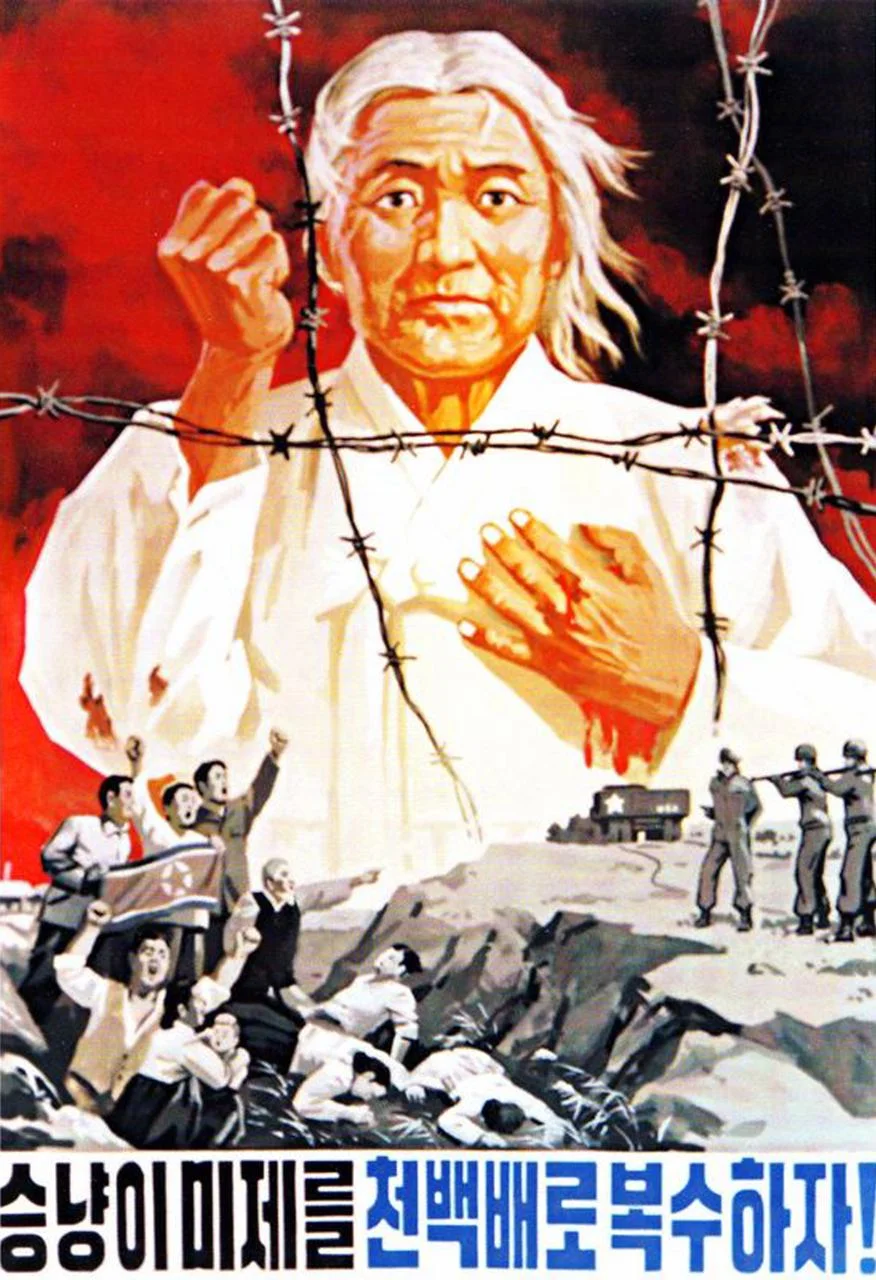

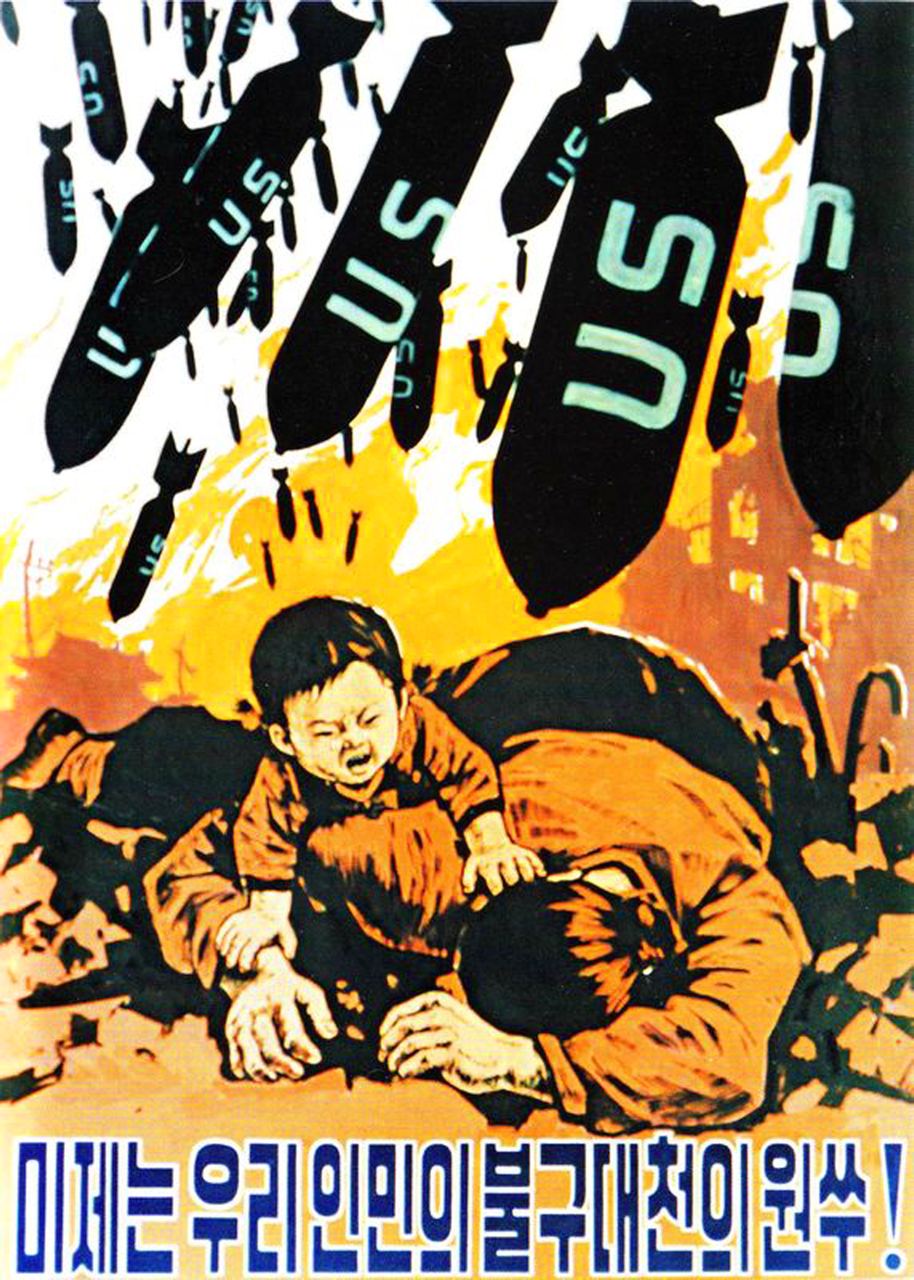

North Korean propaganda poster/Getty Images

It was later revealed that the reported number of guerrillas operating in the mountains of South Korea had been exaggerated. In actuality, in early 1950, there were not ‘around 100,000’ guerrillas but only a few hundred. After Stalin's strategic decision in January 1950, active planning for military operations commenced. Operational plans were drafted by a group of Soviet military advisors who were specially dispatched to Pyongyang. The decision was made to launch the operation on 25 June 1950, on a Sunday morning, a time when most South Korean leaders and officials wouldn't be at their workplaces. As evidenced by South Korean documents and memory, the element of surprise was indeed fully achieved. The South Korean command simply ignored intelligence reports indicating that a full-scale invasion of the South would begin soon.

In the initial weeks of the campaign, the North Korean Army had some remarkable victories. Material and technical superiority played a role in this success. While the United States, cautious of the potentially unpredictable Syngman Rhee, refrained from supplying South Korea with modern offensive weapons, North Korea was equipped with state-of-the-art Soviet technology. The high degree of motivation among North Korean soldiers and officers also contributed significantly to these successes.

Moreover, North Korean units surpassed the enemy in real combat experience. Three of the six North Korean divisions that advanced to the South in the summer of 1950 had been transferred to the North Korean Army from the People's Liberation Army of China a few months before hostilities began. Previously, these divisions had been national units, composed of ethnic Koreans from Manchuria, within the People's Liberation Army.

North-Korean and Chinese troops celebrate their shared victory in South Korea after having driven back an attack of American forces in June 1950. /Getty Images

These ‘Chinese’ divisions had participated in the Chinese Civil War, acquired significant combat experience, and played a crucial role in the initial stages of military operations. Specifically, the 6th Infantry Divisioni

United Nations Against the North

The meeting of the United Nations Security Council meeting on 25 June 1950 was crucial, especially since the Soviet representative abstained. This was due to the fact that the meeting was chaired by a representative of the ‘Chinese Republic’, and at that time, Taiwan was considered as such. During the Chinese Civil War from 1945 to 1950, the ruling Kuomintang Party in China was defeated, and power shifted to the Communist Party led by Mao Zedong. The Kuomintang, though, retained control over Taiwan and some smaller islands. However, until 1971, Taiwan occupied China's seat in the UN. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) demanded the transfer of this seat to the newly formed government of the ‘People's Republic of China’ in Beijing. Since this demand was ignored, the USSR, following established tradition, boycotted such meetings.

At U.N. Security Council, Warren Austin, U.S. delegate, holds Russian-made submachine gun dated 1950, captured by American troops in July 1950. He charges that Russia is delivering arms to North Koreans. 18 сентября 1951/Wikimedia Commons

Some historians argue that Stalin's decision not to participate in the 25 June meeting and, consequently, not to use his veto power was a deliberate political choice, suggesting a shift in his previous stance and an alleged interest in maximizing the expansion of the conflict. While it cannot be completely ruled out, proving this claim with a sufficient degree of certainty seems unlikely. In any case, on 25 June, the Security Council decided to dispatch UN expeditionary forces to the Korean Peninsula. In practice, these forces mainly consisted of American and South Korean units, although military contingents from the United Kingdom and Turkey also undoubtedly played a role.

Meanwhile, North Korean forces continued their southward advance, although the speed of their progress gradually slowed down. North Korean units faced logistical challenges, particularly as railroads became frequent targets of American air raids. Still, by August 1950, around 90 per cent of the Korean Peninsula's territory was controlled by the North Korean government. South Korean forces struggled to maintain control of a small area in the southeast around the city of Pusan, known as the Pusan Perimeter.

On the Verge of the World War III

During this period, the United States actively prepared for a large-scale amphibious operation in Korea, comparable to the Normandy landings of 1944. The chosen landing site was the city of Incheon, the seaport near Seoul. The plan aimed to have American forces coming into the city swiftly seize Seoul and, with the reinforcement of South Korean units and other allied contingents, cut off the entire North Korean Army, which had advanced far to the south, from its rear bases in the North. However, it was impossible to keep the plans for the amphibious operation completely secret. Both Soviet and Chinese intelligence obtained information about the impending landing. Yet, amid intense bombings, primarily targeting railroad junctions and bridges, the North Korean leadership had no opportunity to redeploy troops to the area where the landing was expected.

North Korean аnti american poster during Korean war /Getty Images

The Incheon amphibious operation began on 16 September and unfolded as planned. As anticipated, by 28 September, American-South Korean forces (formally ‘UN forces’) had gained full control of Seoul. The majority of North Korean forces, engaged in battle in the south near Pusan, found themselves completely cut off. Over the ensuing weeks, the remaining North Korean units in the south, surrounded and trapped, were either annihilated or captured. Only a small portion of the encircled North Koreans managed to break through to the north.

Meanwhile, American-South Korean forces initiated a broad offensive toward the North. On 16 October, Pyongyang fell, and by November, in some areas, they had reached the border with China.

Two US Air Force Soldiers pose with a comfort woman in Chinhae South Korea/Getty Images

Thus, ‘wartime happiness’ turned out to be remarkably capricious. In August 1950, over 90 per cent of the Korean Peninsula had been under North Korean control. However, just three months later, in November 1950, 90 per cent of the peninsula was controlled by the opposing side.

Beijing was particularly alarmed by the fact that General MacArthur, the commander of UN forces on the Korean Peninsula, hinted that the campaign could extend into Chinese territory.

The Chinese government repeatedly warned the US that American troops should stop at a certain distance from their border. However, this warning was largely ignored, partly because, based on the experience of the Second World War, American military personnel were used to not taking Chinese forces seriously.

Lieutenant General Douglas MacArthur with other generals makes pre-invasion inspection of landing areas at Inchon from Admiral’s launch, September 15, 1950/Getty Images

In these circumstances, the leadership of the People's Republic of China opted for significant intervention in the conflict, which, at that time, appeared to be completely lost for the North. The situation bore a striking resemblance: in September 1950, the South Korean regime was spared from defeat due to substantial American intervention, and merely two months later, in November 1950, equally substantial Chinese intervention rescued the North Korean regime from potential defeat. Preparations for a potential deployment of Chinese military forces to Korea began as early as May 1950, immediately after Mao Zedong learned about the North's preparations for an invasion of the South. For reasons not discussed here, Stalin and Kim Il Sung deliberately informed Chairman Mao of their offensive-liberation plans several months later.

By the beginning of October, significant Chinese Army forces were already near the Korean border, ready to enter the Korean Peninsula upon receiving the order. However, the decision was not made in Beijing immediately and came after lengthy consultations with Moscow. It was only in mid-October 1950 that Chinese troops began to covertly cross the border and concentrate in positions in the northern part of Korea.

American movie actress Marilyn Monroe entertains a group of soldiers in Korea. 1950/Bettmann/Getty Images

From this moment, the Korean War, which began as a civil war between Korean left and right factions, finally transformed into an international conflict, primarily an American-Chinese war, unfolding on the Korean Peninsula.

An Exhausting Power Parity

The Chinese offensive, which began in November 1950, turned out to be unexpectedly successful. The American and South Korean forces were forced into retreat, and on 4 January 1951, power in Seoul changed hands once again. Only in mid-January was the Chinese advance halted approximately 50 kilometers south of Seoul. This was followed by an American counteroffensive so that by the end of spring 1951, the front line stabilized roughly where the military actions had initially begun a year earlier.

Interestingly, Chinese forces during the war used a ‘political mask’ to avoid creating a situation that could lead to a direct US-China war. It was believed that in Korea, it was not the units of the regular Chinese Army but rather the so-called ‘Chinese People's Volunteers’ operating, with whom the government of the People's Republic of China had no direct affiliation. This diplomatic fiction may have appeared somewhat clumsy, but it helped reduce the likelihood of escalation.

A United Nations soldier in uniform helps a wounded Canadian rifleman to an aid station behind the front lines during the Korean War/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The next two years were a time of positional warfare, during which neither side achieved any decisive success. The focus was on wearing down their opponent. American aviation engaged in the active bombing of Pyongyang and other industrial centers. These bombings yielded no results, except for the destruction of cities and loss of lives, as North Korean armed forces and the decisive Chinese troops were directly supplied by the USSR and China, and American aviation was never completely successful at destroying the railway network and disrupting the supply chain.

The prolonged nature of the war was closely tied to the USSR's stance. Initially, Stalin opposed the conflict, but as the Korean War unfolded, he realized that its protraction served the USSR's strategic interests. Stalin was concerned that Mao Zedong, whom he never entirely trusted, might negotiate with the Americans behind his back. As later events revealed, this concern materialized, albeit much later, in the 1970s. The Korean conflict decreased the chances of an American-Chinese rapprochement and heightened China's economic, financial, and military-technical dependence on the USSR. Additionally, the Korean standoff drained the US, diverting Washington's attention from other global regions. Thus, under these circumstances, Moscow insisted that North Korean and Chinese representatives adopt positions explicitly unacceptable to the US at ceasefire talks, making the extension of the conflict inevitable.

Only after Stalin's death did the USSR allow Chinese and North Korean representatives to make a series of concessions previously deemed unacceptable during ceasefire negotiations. First, the new Soviet leadership did not share Stalin's concerns about China (and as events unfolded, perhaps mistakenly), and second, they wanted to concentrate on internal matters amidst the emerging power struggle within the Kremlin. The outcome of this was the signing of the Armistice Agreement, formally concluding the Korean War on 27 July 1953.

The Four Fractions of Power

The Korean War resulted in massive destruction, with a significant portion of North Korean cities reduced to ashes and many people losing their lives or acquiring disabilities. Despite these severe consequences, the war, for several reasons, led to a significant strengthening of the political positions of Kim Il Sung and his circle, the representatives of the ‘partisan faction’ in the North Korean leadership.

An important thing to remember is the war led to a consolidation of power. From 1945, the leadership of the Workers' Party of Korea had consisted of four factions: Soviet, Yan'an (Chinese), Internal (South Korean), and Manchurian (partisan). These factions were roughly equal in strength and influence, and their relationships were far from ideal, as noted in confidential Soviet diplomatic documents by the late 1940s. For a significant part of the old party elite, Kim Il Sung was merely a provincial field commander during the underground struggle years. Although they had heard something about him, they did not perceive him as a serious leader equal in status to political giants like Pak Hon-yong or Kim Du-bong. But the war fundamentally changed this situation. People who joined the party during the war joined Kim Il Sung's party and perceived him as the leader of the party and country.

Second, the Korean War allowed Kim Il Sung to partially break free from Soviet influence. There were already initial signs in the late 1940s that, despite the declared loyalty to the USSR and its leadership, Kim Il Sung was pursuing his own political agenda. However, practically implementing it was challenging with North Korea under Soviet control. Notably, at the beginning of the Korean War, it was China, not the USSR, that dispatched ground forces to the Korean Peninsula.

The Soviet Union limited its involvement to sending aviation units. Although the presence of Soviet pilots played a significant role, they were still less crucial to the overall outcome of the war than the presence of the Chinese People's Volunteers. In these circumstances, Kim Il Sung had opportunities to navigate the growing contradictions between the Soviet Union and China.

His initial post-war steps were aimed at strengthening his own power by distancing himself from the other three factions. His first target was the Internal faction, primarily composed of the communists who had not left Korea during the colonial period and had participated in the revolutionary movement in Seoul and other major cities. This faction was a relatively easy target as it lacked a foreign sponsor. Repressions against South Korean-born communists began in 1952, and in August 1953, an open political trial took place in Pyongyang, largely copied from the Moscow trials of the 1930s.

Marshal Kim Il Sung signing the Korean Armistice Agreement and the Temporary Agreement Supplementary to the Armistice Agreement at 10pm on July 27, 1953/ Sovfoto/Getty Images

High-ranking party leaders who had conducted illegal revolutionary activities in Seoul during the colonial period were accused of absurd crimes. For instance, it was alleged that the defendants maintained contact with American authorities through an American diplomat (later proven to be far outside Korea at the time). Nevertheless, all the defendants predictably confessed their guilt and were sentenced to death. In December 1955, a trial was held for Pak Hon-yong, who had once been the leader of all Korean communists and later the leader of the Internal faction in the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK) leadership. He was accused of espionage for the United States and Japan and was sentenced to death.

Division of Forces in the USSR

Meanwhile, a crisis was unfolding in the socialist bloc, a crisis that from Kim Il Sung's perspective offered opportunities for success. After Stalin's death in 1953, de-Stalinization began in the USSR, a process that, from Kim Il Sung's point of view, seemed perilous. Kim Il Sung harbored particular dissatisfaction with the principles of collective leadership and the criticism of personality cults.

By that time, North Korea had established a system under Kim Il Sung's sole leadership, and the personality cult had reached proportions comparable to those seen in the Stalin era in the Soviet Union. If the leadership of North Korea had embraced the new Soviet principles of ‘collective leadership’ and ‘criticism of personality cults’, it would have been challenging for Kim Il Sung and his former partisans to retain power—and they were well aware of this.

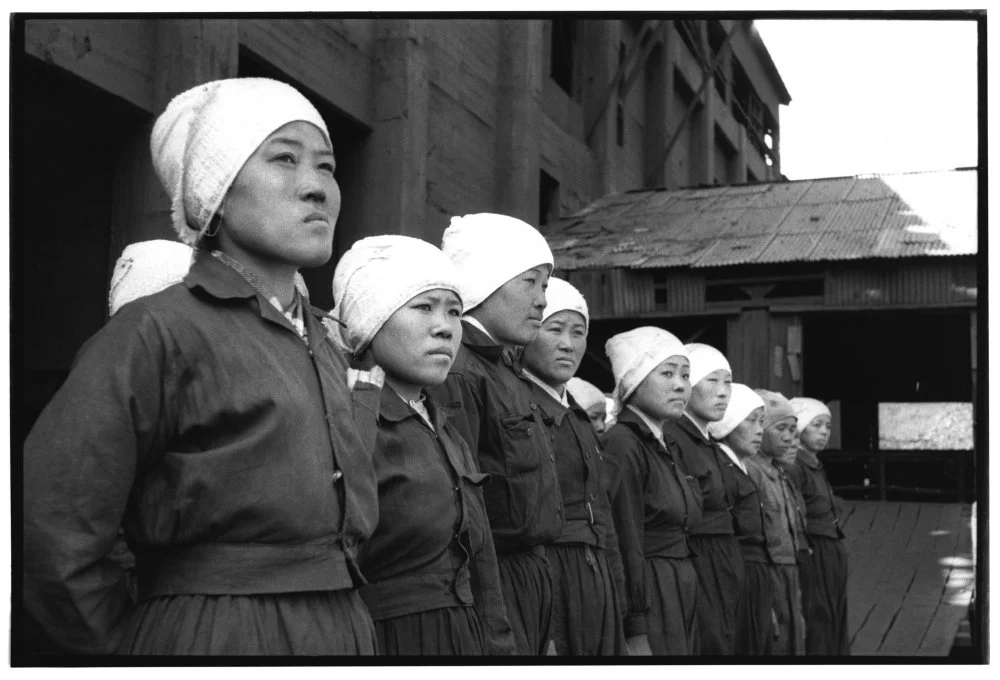

Female mine workers standing in formation/Corbis via Getty Images

The leadership of North Korea also disapproved of the ‘principle of peaceful coexistence’ that was actively promoted by Nikita Khrushchev. This principle inherently involved the necessity of compromises with the imperialist West, and the North Korean leadership feared becoming a victim of such a great power bargain. In Pyongyang, there were concerns that if the USSR actively adhered to the principles of peaceful coexistence, it might prevent North Korea from attempting to reunify the country, even if such an attempt had a high possibility of success.

Finally, the leadership of North Korea could not accept the overall softening of the domestic political course that emerged after Stalin's death. Kim Il Sung and his circle did not understand or share the willingness of the new Soviet leadership to engage in extensive housing construction, invest in the development of small-scale manufacturing, and the sale of food for currency. Both Kim Il Sung and many people in his circle believed that the time to enjoy the achievements of socialism had not yet come. At least it had not come in North Korea, where the focus should be on the development of the heavy industrial segment and, especially, the military-industrial complex (MIC) necessary to eventually achieve the task of reunifying the country.

Propaganda poster depicting a North Korean peasant woman transplanting rice / Photo by Eric Lafforgue/Corbis via Getty Images

After 1953, former Soviet Koreans, members of the Soviet faction, many of whom not only held dual citizenship but were often individuals with dual loyalty, actively advocated for the ‘new course’ in North Korea, which was a course toward de-Stalinization. In these circumstances, Kim Il Sung launched a campaign against the ‘Soviet Koreans’ in late 1955 and succeeded in removing some of them from leadership positions.

However, all these events led to a somewhat unexpected outcome. In the spring of 1956, the Soviet Koreans managed to find common ground with the Yan’an faction, the faction of those who originated from China, and began planning a joint campaign against Kim Il Sung and his policies. Most likely, their goals included the replacement of Kim Il Sung with a more acceptable leader.

Assembly of The Workers' Party of Korea. Kim Il Sung in the middle. 1955 /Wikimedia Commons

However, the plan was not to prepare a state coup as they intended to remove Kim Il Sung from power through legal means. It was implied that at the upcoming plenum of the WPK, the leaders of the opposition would criticize Kim Il Sung and demand a revision of the country's policies, possibly leading to Kim Il Sung being removed from top positions. They hoped to garner support from the majority of the WPK members who would vote for their proposed resolutions. The opposition informed both the Soviet and Chinese embassies about their plans. In theory, with good preparation and some luck, this plan could have worked, as around the same time, leadership changes occurred in some socialist countries following a similar scenario. However, in Korea, things did not unfold as expected.

The attempt to sideline Kim Il Sung took place at the plenum of the Central Committee of the WPK on 30–31 August 1956. However, this attempt ended in failure. Kim Il Sung was aware of the impending opposition and, actively leveraging the ‘administrative resource’, secured the loyalty of the majority of the Central Committee members in advance. As a result, the presentation by the opposition group, consisting of a dozen high-ranking party officials with Soviet and Chinese backgrounds, was easily suppressed, and supporters of the opposition were removed from official positions and, in some cases, expelled from the party.

However, a few opposition figures from the Yan’an faction managed to escape to China, where they had strong connections. They complained about the situation to Mao Zedong himself, who maintained a rather cold attitude toward Kim Il Sung. The Chinese leader, as he had repeatedly conveyed to Soviet diplomats, could not forgive Kim Il Sung for the ill-considered decision to initiate the Korean War.

North Korea and China have been close since the days of Kim Il-sung and Mao Zedong.

On the other hand, the Korean opposition, effectively represented by the North Korean Ambassador to the USSR, Lee Sang-jo, approached the Soviet leadership with a proposal to send a joint Soviet-Chinese delegation to North Korea to restore order. The idea was that this delegation would compel the North Korean leadership to rehabilitate opposition figures and reconsider its policies in light of Moscow's new course.i

Between USSR and China

The proposal was accepted, and the delegation was dispatched to Pyongyang in September 1956. A.I. Mikoyan, overseeing relations with socialist countries, led the Soviet side, while Peng Dehuai, formerly the commander of the Chinese People's Volunteers in Korea, led the Chinese side. Formally, Kim Il Sung could not resist the demands of the two neighboring superpowers, one of which was his main sponsor, while the other maintained a military contingent in North Korea that outnumbered the entire North Korean Army at the time. Nevertheless, the delegation failed to accomplish its mission as Kim Il Sung skillfully delayed the situation and managed to avoid any blows. At the new Central Committee plenum convened in September 1956, with the participation of the Soviet and Chinese delegations, Kim Il Sung engaged in self-criticism and announced the rehabilitation of participants in the August uprising. However, this statement had a purely ritualistic nature as these individuals never returned to their positions. Through the following year, Kim Il Sung tried to buy time and avoid implementing the decisions he had reluctantly agreed to under Chinese and Soviet pressure.

Soviet poster: «Long live the eternal and indestructible Soviet-Korean friendship!» by Alexei Lavrov. 1960 / Wikimedia Commons

The deteriorating relations between the Soviet Union and China in 1957 were beneficial to Kim Il Sung and his supporters. The Chinese leadership, including Mao Zedong and Peng Dehuai, apologized to Kim Il Sung for the delegation's visit in September 1956, considering it an interference in the internal affairs of North Korea. Mao Zedong correctly noted that this decision was an example of meddling in the internal affairs of North Korea. Understandably, this act of contrition by the Great Helmsman was motivated by practical considerations: relations between China and Moscow were rapidly worsening, and it was crucial for Beijing to win North Korea to its side—or at least prevent North Korea from siding with Moscow in the emerging conflict. Meanwhile, Kim Il Sung initiated measures aimed at reducing Soviet influence, including what is now referred to as ‘soft power’. Starting from the late 1950s, there was a rapid deterioration in relations between the USSR and North Korea. The North Korean side actively restricted contact with the USSR—both private and official as well as scientific—seeing it not as a teacher but as a source of dangerous ideological contagion in the new circumstances. The dispatch of North Korean students to the USSR and Eastern European countries almost ceased for two decades. Several incidents contributed to this, where North Korean students in the USSR and Eastern European countries became defectors, receiving asylum in those socialist countries where they were located.

Korean woman in front of the tank/Getty Images

In the early 1960s, the North Korean postal service stopped delivering letters from the Soviet Union to recipients, and it also ceased sending letters from North Korean citizens to the Soviet Union (although there were a few exceptions to this rule). Women from the USSR and other socialist countries who had previously married North Koreans were forced to separate from them in the early and mid-1960s, though not by their choice. Divorce from foreign wives became a mandatory requirement imposed on North Koreans by their superiors. After the divorce, women and children were expelled abroad, and for several decades, they had no opportunity to contact their fathers.

In the late 1950s, a campaign to oust officials of Chinese and Soviet origin from North Korea began. Some of them faced repression, imprisonment, and even execution. However, these violent measures were more aimed at creating psychological pressure on the ‘undesirable elements’. It was implied that the party workers who had arrived in North Korea from China or the USSR, understanding that staying in Korea was becoming risky for them, would voluntarily leave the country. In most cases, these calculations worked, and significant supporters of both the Yan'an and especially the Soviet factions left North Korea en masse between 1958 and 1962.

All of these policies should not be surprising when one remembers that from the very beginning of his political life, Kim Il Sung was more of a nationalist than a communist. The Soviet leadership sought to use him as a tool to achieve its own geopolitical goals, but this process was by no means a one-way street. He also sought to use the Soviet leadership for his own purposes. It seems that in this peculiar competition, Kim Il Sung ultimately emerged victorious. He had a clear goal, shared by many people in his circle and in North Korean society as a whole: the creation of a maximally independent Korean state, organized according to the models that both Kim Il Sung and a significant part of the country's population found attractive.