His life is a true legend. The writer, who lived only 44 years, dedicated himself to creativity in the last 10 years of his life.

- 1. THE INACCESSIBLE HIMALAYAS—WHY ARE THEY LIKE THIS?

- 2. THE FIRST UNCERTAINTY—DATE OF BIRTH

- 3. FROM ZHETYSSU TO TASHKENT

- 4. STUDENT OF "AVERAGE POLITICAL PERFORMANCE"

- 5. FATIMA, HIS ETERNAL MUSE

- 6. LET MY SON BECOME A SHOEMAKER

- 7. SOUNDS OF "KÜISHI"

- 8. CREATION OF "QULAGER"

- 9. THE DEATH OF QULAGER

- 10. THE LAST UNCERTAINTY: "IT TURNS OUT ILYAS IS NOT DEAD, HE IS ALIVE"

During this period, he produced 15 poems, several novels, and plays. He also worked in government positions, constantly wrote articles for newspapers and magazines, and collected samples of Kazakh folklore, tales, legends, and myths. His collected works are published in 20 volumes. However, some of his translations and poems have not yet been found. He was one of the first authors and founders of major newspapers such as "Jas Alaş," "Egemen Qazaqstan," and "Kazakh Literature." He also founded the Writers' Union of Kazakhstan and was one of its first chairmen. Particularly noteworthy is his contribution to the development of Kazakhstan's publishing industry. His figure stands out from the first portents of the early 20th century. If asked who the first Kazakh professional journalist was, we would first name Ilyas Jansugurov.

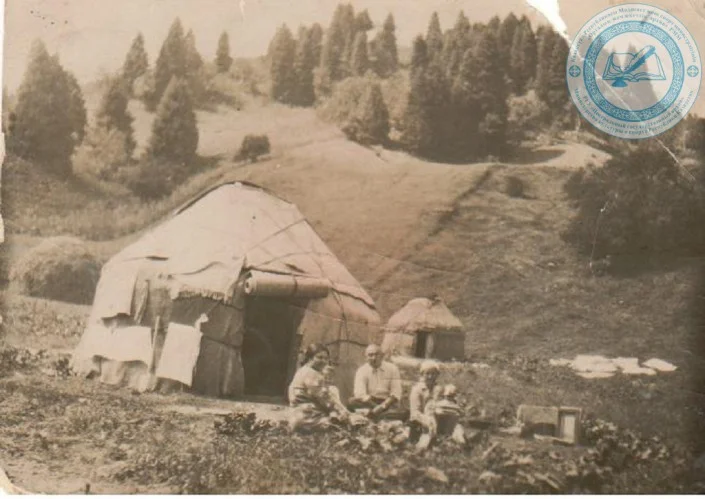

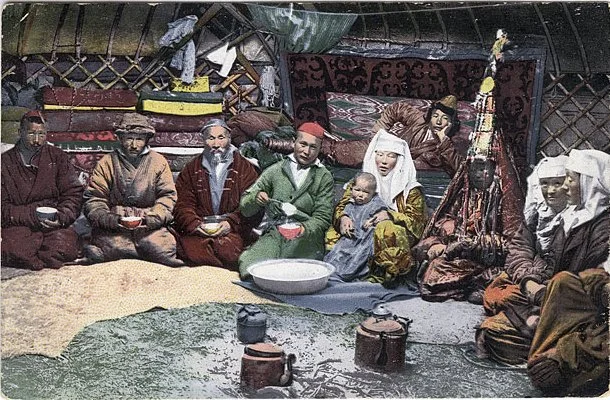

Ilyas Zhansugurov in front of yurt/Central State Archive

But in the end, he became a victim of the Soviet Communist system. The poet, who impressively and touchingly described the tragic end of the stallion (Qūlager) treacherously killed by envious people, repeated Qūlager's fate. Among the people, he is called "Qūlager of Legends." Let us recall some moments from the biography and creativity of this poet, where myths and reality are closely intertwined.

THE INACCESSIBLE HIMALAYAS—WHY ARE THEY LIKE THIS?

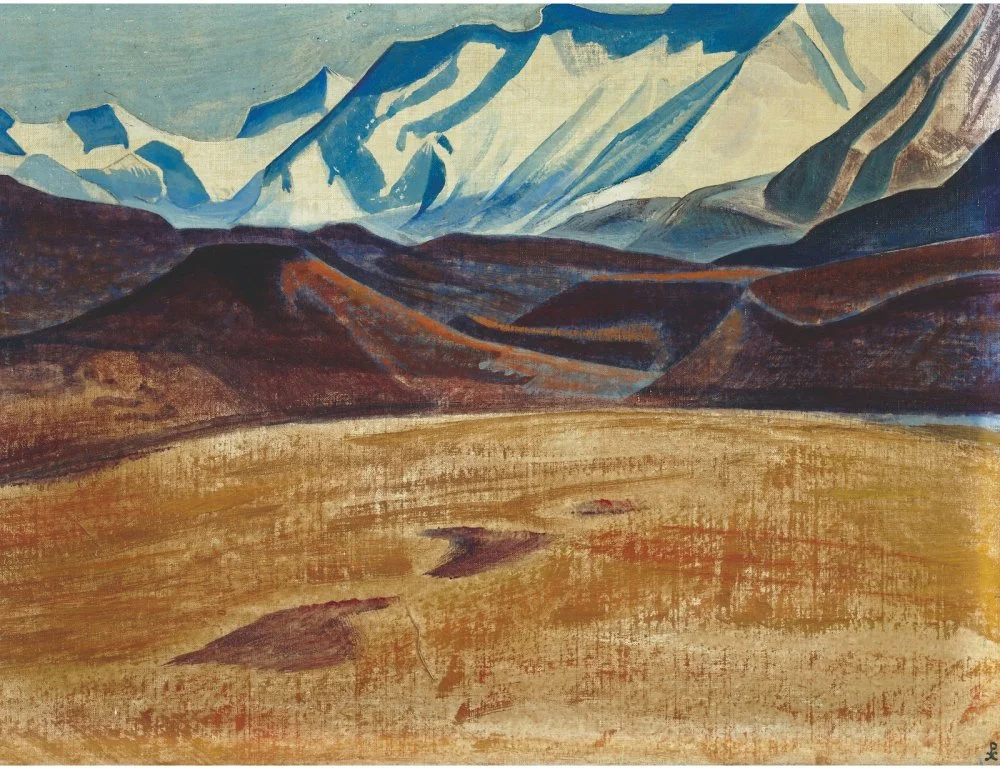

In 1929, Ilyas Jansugurov wrote a voluminous poem about the Himalayas. Since my childhood, I have been amazed that a poet living in a remote corner of Asia created such a remarkable and profound work about the greatest mountain system on the continent. We were also interested in information about the Himalayan peaks, eagerly absorbing available data about them. I still love rereading this poem, as there the author not only captured the giant Himalayan mountain chain but also allegorically described the grim political situation on the Asian continent. The poem is called "Question," and in parentheses, as an explanation, there is a subtitle "East inhabited by wanderers." In the first part of the poem, the author feels pity for the Himalayas, which cannot recharge with energy from the sun, wind, light, and repeats the question, "Why the inaccessible Himalayas are like that?" (In my childhood, I read: "Why the giant Himalayas are like that?"). And in the second part, the poet himself answers the question he posed. Concluding his work with "There is power in the Himalayas" and "there is a great fire in the Himalayas," he asserts that the time is near when the great peaks will appear from the veil of fog and will heal themselves from the ailment and he ends the work with hopeful stanzas.

Nicholas roerich. Depsang plains. 1925 or 1926/Wikimedia Commons

The Himalayas are tightly wrapped in legends. Since this is the highest mountain range in the world, many people try to conquer its peaks. We respect the bravery of climbers, their willingness to risk their lives to reach those summits. For Kazakhs, Ilyas Jansugurov is also a huge Himalayan peak. He was truly a unique personality in whose fate legends and reality intertwined inseparably. His poems "Qūlager" and "Küişı" are epoch-making works; the creation of such epic works with an unprecedentedly wide canvas was a new level in the national poetry.

The book Kulager/From open sources

THE FIRST UNCERTAINTY—DATE OF BIRTH

There are many questions and mysterious moments in his life.

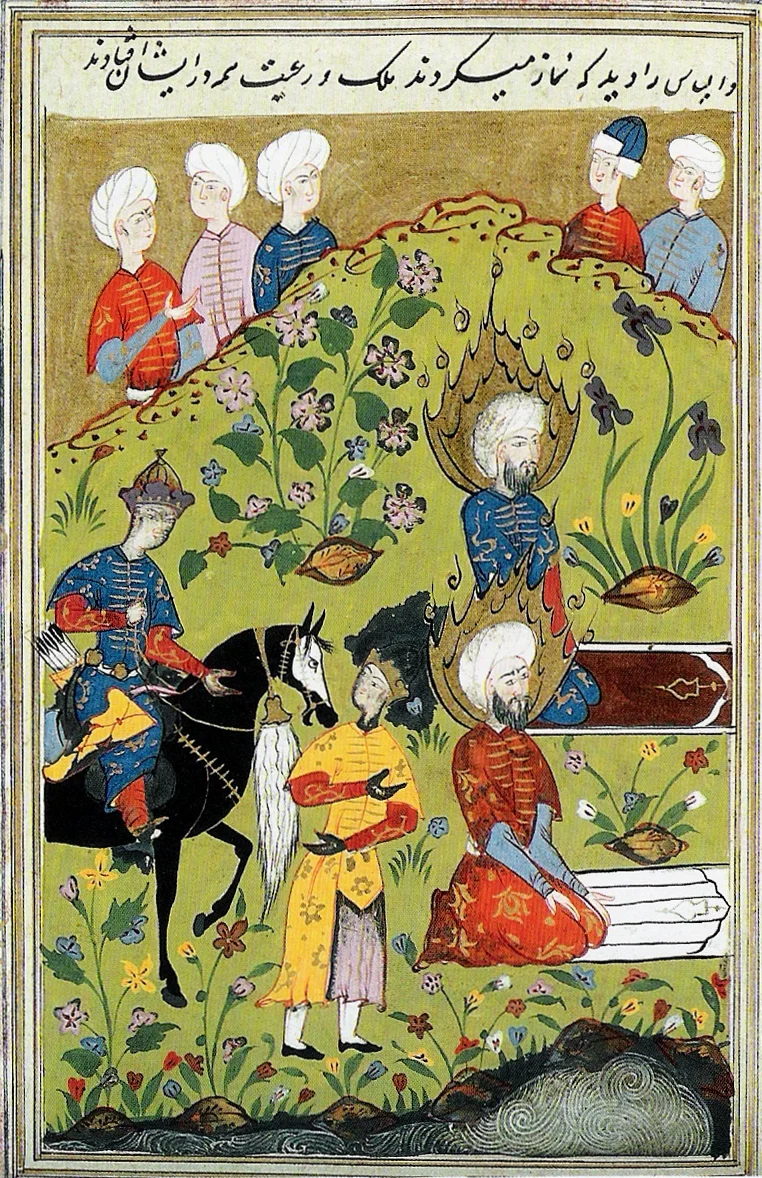

There were those who claimed that Ilyas Jansugurov was born in 1894 in the fourth village of today's Aksu district of the Zhetysu region. According to some experts in Ilyas’s history, he was born in the locality of Kindiktobe. According to sources where it is not possible to determine where facts end and legend begins, the name Ilyas was given to him by the famous qobyz player Molyukbai. Molyukbai was born in and lived in Aksu but was also forced to hide in Semey due to his opposition to the Russian Empire. Once he became a specially invited guest at Zhansugur’s newborn son naming ceremony, who was his close friend.

They say that the shaman-baqshi after his arrival played the qobyz and told the villagers legends about Korkyt, Asan-Kaigy, Shal-Kyiz, and performed epics for a long time. Then, after reading the azan, he gave the name to his friend's son. He named him "Qyzyr-Ilias." Qyzyr is a highly revered saintly figure among Kazakhs. They say Qyzyr is a prophet. There is a belief that he lives, travels around the world, and only those to whom he favors can see him. Molyukbai himself was a shaman, healer, and very devout person.

A depiction of Elijah and Khidr praying together from an illuminated manuscript version of Stories of the Prophets. 427 Year of the Hijrah (1305 year)/Wikimedia commons

Although shamanism and religiosity are considered mutually exclusive phenomena, there was a time of harmony when Tengrianism and Islam coexisted in full harmony. Kazakhs respected the mullah but also did not reject the shaman-baqshi. His early works, written during his studies at the Mamaniya school, as well as the books he read, he signed with the name Qyzyr-Ilias, but later he began to call himself Ilyas Jansugurov. They also say that his decision to shorten his name and call himself Ilyas was influenced by the educator Bilyal Suleyev, his friend, and the first husband of his wife Fatima Gabitova. In some sources about the poet, it is mentioned that the hill where the umbilical cord of Qyzyr-Ilias was buried became known as "Kindik tobe" — "Umbilical Hill." Now a commemorative stone stands on this site, specially installed by the husband of his daughter Ilfa.

We know the year of the poet's birth for certain, but the date remains unknown. He himself writes that he was born "by summer." They say that his friends, the poet Saken Seifullin and writer Beimbet Mailin, told him: "Europeans celebrate birthdays. Let's establish your exact birth date" and set his birthday as May 1. Some sources indicate the poet's birth date as May 14. And on Wikipedia — May 5. According to experts in Ilyas’s history, it is impossible to determine the exact birth date of the poet.

Ilyas Zhansugurov, Mukhtar Auezov and their friend on horseback/Central State Archive

Thus, the transformation of Qyzyr-Ilias into Ilyas, the uncertainty of his birth date (May 1, 5, and 14 dates were established), and his statement that he came into this world "by summer" once again testify that there is much unknown in his legendary life from birth. From the moment of being named by such a holy man as the shaman Molyukbai, began the whirlwind of the short but saturated with bright and dark events life of the future küişı poet and writer. (Molyukbai is known as a shaman-baqshi, healer, and doctor. Many legends circulate about Molyukbai, which are reflected in many literary works and poems. They say that when Molyukbai touched the strings of the qobyz with his bow, the world would became different, and his qobyz, in a hurry to pour out its sorrow, emitted sad kui even when the shaman was not around. The qobyz that belonged to Molyukbai is kept in the Ilyas Jansugurov museum in Taldykorgan). It is popularly believed that the prototype of the main character in the poem "Küişı" is the shaman Molyukbai himself.

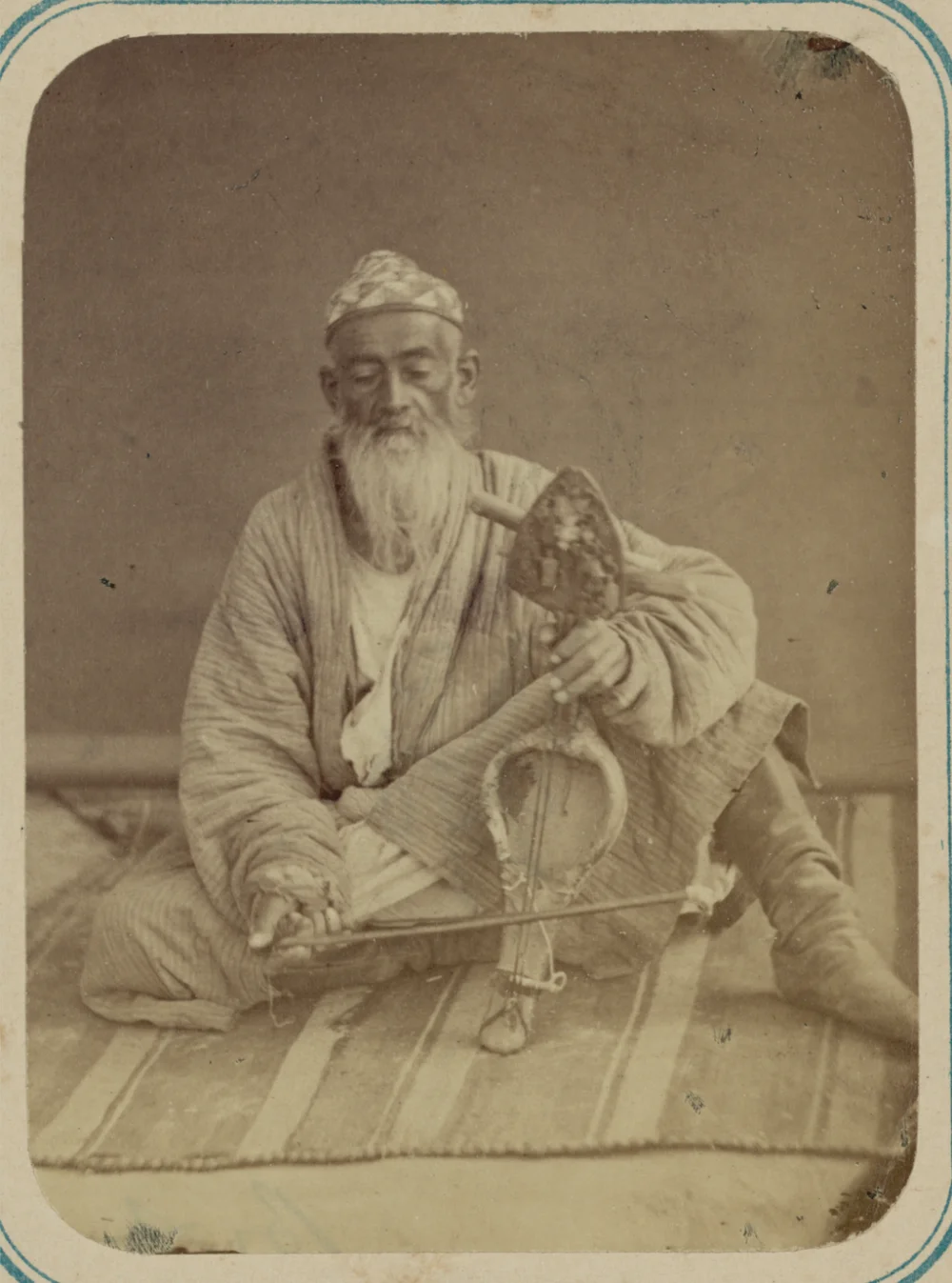

Pastimes of Central Asians. A Musician Playing a Kobyz/Kauz. This photograph is from the ethnographical part of the Turkestan Album. Between 1865 and 1872/Wikimedia commons

FROM ZHETYSSU TO TASHKENT

Initially, Ilyas studied at the Mamaniya school in the Zhetysu region. It was 1914. He received his further education from his father. Zhansugur was a küişı and had a phenomenal memory that allowed reciting epics by heart. He was also considered a brilliant orator. It is likely that Ilyas’s father was against his further studies. He did not want to let go of his son, who lost his mother at the age of four, and wanted him to study with the village mullah.

But Ilyas did not give in to his father's persuasions. He made his own decision, declaring: "What knowledge will I gain from him? What besides memorizing verses will he give me?" The future poet was particularly influenced by his first teacher at the Mamaniya school, Bilyal Suleyev. Bilyal Suleyev gave his student extensive knowledge of Russian and European literature, facilitated his acquaintance and friendship with the educated figures of the Alash movement, especially with Mukhtar Auezov.

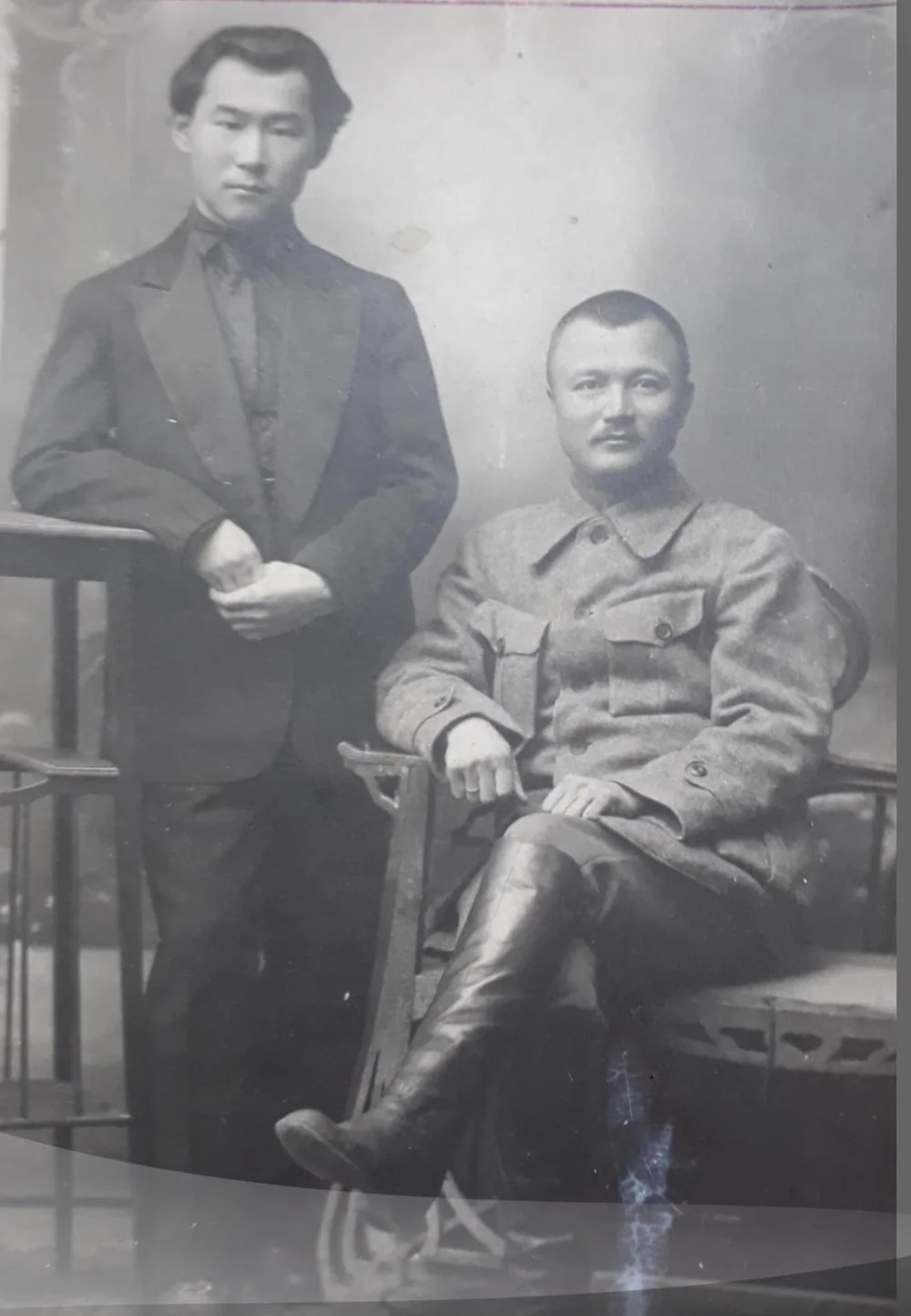

Bilal Suleev/personal archive of Eldos Toktarbai/Alash Electronic Library

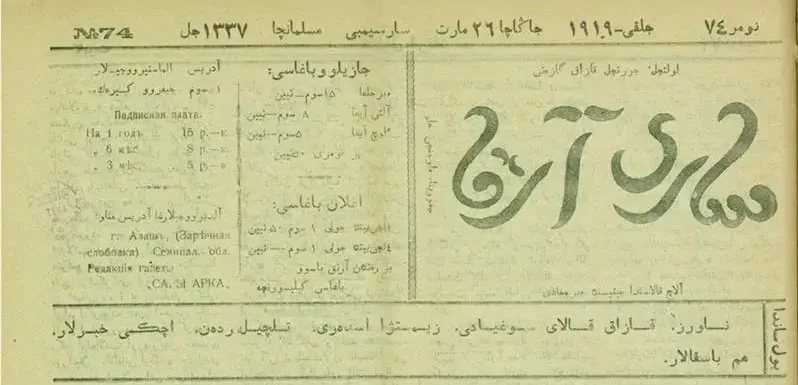

Kazakhs have an expression "having seen Tashkent." The notion of a person who has seen Tashkent corresponds to the idea of a highly educated personality with broad views. In 1920, Ilyas continued his education by enrolling in 3-year teacher courses in Tashkent on the recommendation of his first teacher, Bilyal Suleyev. Bilyal Suleyev taught him Russian, and in Tashkent, Ilyas deepened this knowledge and met young people from Central Asia who, like him, were passionate about acquiring knowledge. Ilyas began writing in 1912. His poems "Saryarqa" and "Wishes" were first published in the "Saryarqa" newspaper, which was issued in Semipalatinsk. The years spent in Tashkent expanded the horizons of the themes raised by the poet, which pushed him to create poems of a different genre. It was a time when the Communist Party established total control in Central Asia, during the peak of political campaigns. Therefore, the poet's works from this period are noticeably influenced by politics.

Sary Arka newspaper. No.74. March 26, 1919/Kaz.inform.kz

STUDENT OF "AVERAGE POLITICAL PERFORMANCE"

In Ilyas Jansugurov’s life, Moscow held a special place. In 1925, he went to study at the Moscow Academy of Journalism. In modern terms, Ilyas Jansugurov was the first professional and certified journalist from Kazakhstan. The three years he spent in Moscow have not been fully studied. However, it can be said that these years were of particular significance to him, fostering a deep understanding of global geopolitics and contemporary trends. It was during these years of study that he was motivated to translate the works of the best Russian and world writers. Through his efforts, the works of Pushkin, Lermontov, Nekrasov, Gorky, Heinrich Heine, and Victor Hugo were eloquently translated into the Kazakh language. We believe that the essence of the question: "Why are they like that, the Himalayan peaks?" posed by the poet should be connected with these moments. The poet, feeling himself a descendant of a nomadic people and an Asian, could not help but be aware of the difference between Western civilization and the communist system and feel concern for the fate of dependent Asian countries. Through his poems about the Himalayas, he wishes for a better destiny for the East. His wish for the East to achieve prosperity, to awaken, gain freedom, and be charged with the energy of "sun," "light," and "wind" was quite fitting. It is natural that he questions why the Himalayas, despite their height, are trapped by clouds, ice, and storms. It is reasonable to believe that during his time in Moscow, he deeply studied Asian identity.

Photo from the archive of the Zhansugurov-Zhandosov family: Maxim Gorky, Fatima Gabitova (according to another version Polina Kusurgasheva) and Ilyas Zhansugurov. During his stay in Moscow at the USSR Writers' Congress, a meeting with M.Gorky was held at his dacha/Wikimedia Commons

By asking, "Why are they like that, the Himalayan peaks?", he was also thinking about the fate of his homeland, far from the Himalayas. This is where the sharpness of the question lies – such is the opinion expressed by some literary critics sometimes. After all, in the poem "Steppe," written in 1930, describing the Kazakh mountains, rivers, lakes, and deserts spread out between the Altai and Atyrau, he seems to repeat the question about the Himalayas but shifts the focus somewhat. He also does not forget the moments when beautiful nature appears gray, the peaks of majestic mountains are shrouded in clouds, and the gurgling clear water disappears into the sand. He also refers to the important historical events, such as " Aqtaban şūbyryndy, alqaköl sūlama,"i

In the student records of student Jansugurov, provided by the Moscow Institute of Journalism, in characteristics section it was stated: "Political Studies performance: average. Disciplined and restrained." This one phrase elusively explains a lot... "Why are they like that, the Himalayan peaks?" A question worth pondering!

Ilyas Zhansugurov, on the right side of the photo. Pyatigorsk. 1936/Central State Archive

FATIMA, HIS ETERNAL MUSE

His family life is also shrouded in uncertainties. Throughout his life, he was married four times. His marriage to his first wife, Jamila, was short-lived. There are no definitive answers to how they got married or the reasons for their divorce. After returning from Tashkent, he married Amansha Berentaiqyzy. When Ilyas went to Moscow, his wife Amansha stayed home. She was pregnant and soon died during childbirth. He learned about her death from friends after returning to Almaty. Amansha was also an educated woman. Her last letter to Ilyas has been preserved. "Ilyas, I leave you these rings and other things. Keep them safe. I have flamed up... and faded away in this undimmed world. You were not there by my side. I was not destined to see you. Farewell!"—these were the brief final lines from his loving wife.

Fatima Gabitova/From open sources

After returning from Moscow, Ilyas Jansugurov went to Kyzylorda, then to the capital of the republic, where he married for the third time. Fatima (Batima) Törebayeva was his chosen one. On February 21, 1930, their first child, Sayat, was born, and a year later, their daughter, Saira. When Saira was six months old, Fatima took her daughter and went to Moscow to study. Unfortunately, while her mother was away, there was an accident, and Saira died. According to Sayat, the death of Saira caused a rift in the relationship between his father and mother. Ilyas blamed Fatima for this and decided to end their marriage. His fourth wife was Fatima Gabitova, who was destined to be the muse of three Kazakh giants, and three friends: Bilyal Suleyev, Ilyas Jansugurov, and Mukhtar Auezov.

In the life of Ilyas Jansugurov, Bilyal Suleyev holds a special place. He was his first teacher, mentor, friend, and inspirer, through whom he received his education in Tashkent. In 1932, Ilyas married his friend's wife. At that time, Bilyal Suleyev was in prison, although he was soon released. It is unknown how he reacted to the decision of Ilyas and Fatima, how he coped with it, but some sources indicate that he could not forgive them and left Almaty. And not without reason… However, it is also known that Ilyas Jansugurov had long been in love with Fatima Gabitova. This became clear from Fatima's letters to Ilyas. Ilyas secretly wrote and sent poems to his muse. In response to one of these letters, Fatima wrote:

"You are a very talented poet, capable of creating a majestic arch of eloquent words... Now, instead of your sorrowful letters, I want to read the poems of passion written by you, the poems that fully reflect the image of our people. I will not write to you until you amaze the country with your literary achievements. And you should not write to me!"

On May 3, 1937. On the left, Fatima Gabitova with little Ilfa Zhansugurova in her arms. In the center, Ilyas Zhansugurov holds Umut's daughter in his arms, and Azat Suleev sits to Umut's right. Janibek Suleev stands between Fatima and Ilyas. On the far right is Huppizhamal, Fatima Gabitova's maternal aunt. A housekeeper (name unknown) is standing over her. Ilyas's nephew Bulatkhan is standing to her left/From open sources

LET MY SON BECOME A SHOEMAKER

Ilyas Jansugurov lived with Fatima Gabitova for five years in their marriage, during that time she gave him three children: daughters Umit and Ilfa, and their son Bulat. All three dedicated their lives to preserving and promoting their father's work, collecting his legacy and translating it into other languages.

Bulat was born while Ilyas Jansugurov was imprisoned. His wife, Fatima Gabitova, visited the prison every other day hoping to see Ilyas. She managed to get the permission to meet him in person only once. Upon seeing the newborn Bulat, Ilyas said, "Son, we had to meet in such a place." He then instructed his wife, "Let my son be a shoemaker, teach him to make shoes." The investigator, who overheard Ilyas's words, sarcastically remarked, "Your son will probably become a writer like you." To this, the poet replied, "Better to be a shoemaker and live freely than to be a writer punished without guilt." However, Bulat did not become a shoemaker. He became a renowned screenwriter. Throughout his life, he collected his father's legacy and translated it into Russian. He passed away in 2004 in Almaty.

Bоlat Gabitov/From open sources

SOUNDS OF "KÜISHI"

"Recently, in our aul, a Küishi named Toytan passed away. He took about a hundred küis with him. When a person dies, others are born to take their place. But when a küi dies, it cannot be revived."

This is an excerpt from Ilyas Jansugurov's speech at a meeting he organized in Jetysu to study Kazakh küis. The last five years of Ilyas Jansugurov's life can be called his most fruitful and inspiring period. It was during these years, after marrying Fatima Gabitova, that he created his most brilliant works. His two most perfect and famous poems were written during this time. The poems "Küishi" (1934) and "Qulager" (1936) are rightfully considered beautiful examples of Kazakh literature. Notably, the famous Kazakh writer Abish Kekilbayev highly praised these two poems, calling them exceptional and noting, "These works are also the greatest compositions that can be placed on the highest shelf of our national literature's library alongside the famous epic 'The Path of Abai.'

A shot from the film Kulager (Trizna)/From open sources

In the poem "Küishi," the author revisits another prominent work known as "Küi," which was created in 1929, revives its artistic techniques, moving away from mere enumeration and delving into new depths of human psychology, shifting from generalized description to very personal expression. We know that Ilyas himself was a great lover and connoisseur of küis and skillfully played ancient küis on the dombra. Therefore, it was no coincidence that he held a meeting to study these works. Another fact is that Ilyas's performance of küis impressed Alexander Zatayevich, who collected and notated the melodies of Kazakh küis and songs. On the title page of a book with his autograph gifted to Ilyas, Zatayevich wrote: "To my best friend. Thank you for your help."

"Küishi" is a symphony in verse. Reading the poem, you become amazed by the author's masterful skill in conveying the sound of a küi through words. The work consists of seven chapters and captivates with its perfection, breathing inspiration, and vividly and beautifully depicting the inner world, hidden dreams, passions of the flesh, and the soul's aspirations of the characters. It is impossible to read this without admiration. Along with the küi, performed by the küishi, which consists of 99 parts, a complete picture of the steppe unfolds before your eyes. Like beads strung on a thread, images of a girl's dowry and the rich, luxurious setting of her yurt appear before your eyes. The essence and meaning of nomadic life are captured in the unique scenes created by the author, and as if peering into an ethnographic album with artistic images, your soul receives true spiritual pleasure from touching the aesthetic magical world.

The plot of the work is not complex

Archival photos of Kazakhs/Wikimedia Commons

The number of characters is also small. Kenesary, a descendant of Ablai, the last Kazakh khan, arrives in Jetysu. People greet him with joy and honors, offering a white-grey horse as a prize for the Küishi. A Jetysu Küishi arrives at Kenesary's camp and plays küis. The khan's younger sister Karashashi

What a girl! To cover her delicate neck with kisses,

To burn with her in passion for sixty years!

And to be invisible to any living being,

To become a bird like a fairy peri!

The melody of the küi immerses them both in a sweet state of bliss, as if they have satisfied their sexual desire while caressing each other. The poet depicts this moment with hazy images. The reader continues to wonder what really happened, whether the Küishi and Karashash satisfied their passion or dissolved in the flow of the küi and found delight in it. The subtleties of psychological moments in the work are very difficult to clarify even in this article. The poet describes Karashash's beauty as follows:

Through her transparent delicate skin was visible,

Every sip of Isfahan wine.

In this work, there is a scene where the Küishi, captivated by the girl's beauty, is in complete turmoil and cannot control his fingers, distorting the küi's melody.

"Küishi" can rightfully be called one of the best works about küis. The expressive means, personification, antithesis, and comparison of old mythological characters with Karashash cannot fail to impress.

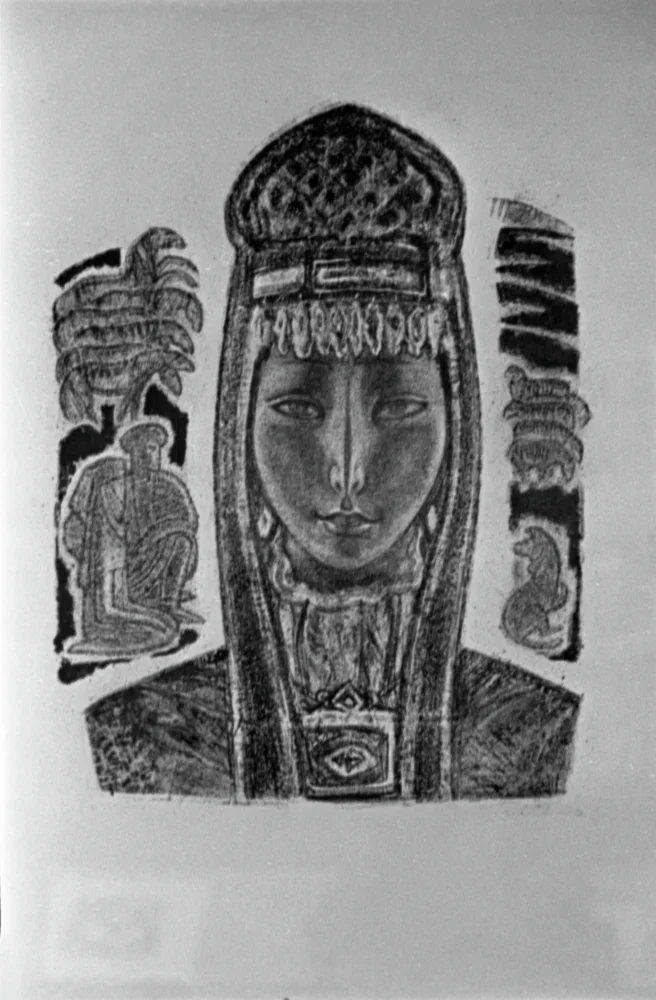

Evgeny Matveevich Sidorkin. Beauty. 1966/RIA

CREATION OF "QULAGER"

If you are even slightly familiar with Kazakh culture and literature, you definitely know or at least have heard of Qulager. In Kazakh history and epics, there are many stories about horses, where the horses are highly revered and called "man's wings." Even in fairy tales and legends, there is no hero without a horse, just as there is no historical event without a horse. Horses, the most reliable companions of khans and batyrs, such as Taibuyryl, Baishubar, Bozaigur, Qubas At, Qaraqasqa, and others, hold a special place in Kazakh literature. However, among them, Qulager stands out. Qulager is not a hero of an epic but a famous steed of Aqan Sery, a composer and singer who lived in the 19th century. It would not be an exaggeration to say that Qulager occupies a special place in Kazakh literature. Based on Aqan Sery's song "Qulager," a unique poem has been written, and numerous legends exist. Documentaries and feature films have been made about Qulager's tragic fate, and many theatrical productions have been staged. Literary critics call Ilyas Jansugurov the "Qulager of poetry."

The poem "Qulager," one of Ilyas Jansugurov's finest works, was written in 1936. It is said that the literary community of Almaty eagerly anticipated the poem's release even before Jansugurov began writing it. The public, delighted by the masterpiece "Küishi," awaited another great work about the legendary steed. The story of Akan Sery and Qulager is well known to everyone. There is not a single Kazakh who does not know the song "Qulager." Now, Ilyas was to turn it into a poem.

For people raised on epics, this poem was something new. According to some sources, Jansugurov traveled to Kokshetau specifically to study the details of the event to transform Akan's "Qulager" into a poem.

To this day, much research has been conducted on the history of the steed named Qulager, killed by Batyrash at the grand memorial service for Sagynay.i

Furthermore, "Qulager" is considered the best example and standard of Kazakh poetry in the 20th century.

Evgeny Matveevich Sidorkin. Baige. 1964/RIA

In both "Küishi" and "Qulager," Jansugurov extensively utilized the richness and power of the Kazakh language. Abish Kekilbayev wrote about this: "Ilyas Jansugurov demonstrated foresight and leadership in perfecting the flexibility of the native language, inherent in realistic artistic thought, delving into the social and philosophical depths of our national material, not limited to the confines of the everyday life, and left behind an immortal model for emulation. Jansugurov's innovation not only brought dizzying success to him as an individual poet but also elevated the entire national poetry to a new historical level. "

According to Kekilbayev, just as Pushkin and Lermontov revitalized the Russian language by refining its artistic arsenal and introducing it into literary circulation, Ilyas, through his poems, infused the rich Kazakh language with that special energy.

Indeed, Ilyas Jansugurov was an artist who brilliantly harmonized epic poetics and modern poetry, encompassing both old and new in his imagery, thereby bringing a unique color to national poetry.

A shot from the film Kulager (Trizna)/From open sources

THE DEATH OF QULAGER

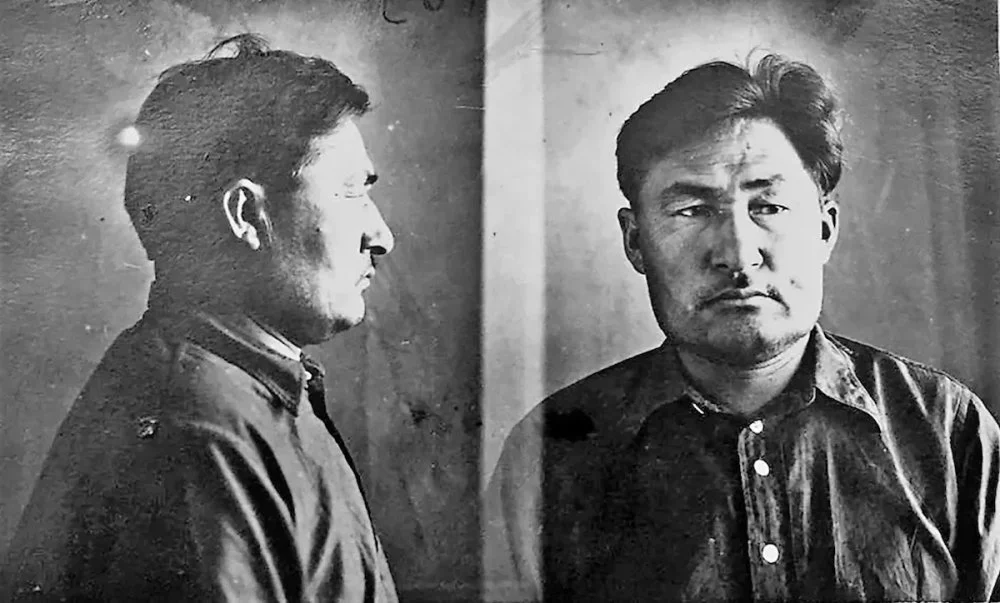

In August 1937, the NKVD arrested Ilyas. He was accused of espionage in favor of Japan, and on February 26, 1938, he was sentenced to execution in Almaty. He was buried along with 36 other victims who were executed on the same day in the village of Janalyq in today's Talgar district.

His death, like deaths of many citizens of that time, was facilitated by anonymous denunciations. When the first summons for interrogation arrived, his wife, Fatima Gabitova, urged him to cross the Alatau mountains and flee to Issyk-Kul. However, Ilyas replied that he had committed no crimes and therefore did not intend to hide from the NKVD. He went to the investigator and was immediately arrested, never to return home.

According to his daughter Ilfa's recollections, NKVD officers came to their house in the middle of the night and took away the poet's entire archive, books, and manuscripts. Only some records wrapped in felt and left in a cupboard survived. Fatima Gabitova handed these over to her relative Ospan Jilkayev, who worked in the NKVD. He returned them after Ilyas Jansugurov was posthumously rehabilitated. However, many of his works were never recovered, including the poem "Qulager."

After the poet's rehabilitation in 1957, Mukhtar Auezov initiated the search for the poem, sending inquiries to all relevant institutions. He said, "We must find Ilyas' 'Qulager.' It is a great poem." Attempts to locate the poem in archives, which had been published in four issues of the newspaper "Socialist Kazakhstan," were unsuccessful. The text had been cut out from all its issues. It was not to be found in neither of the libraries. Luckily, the work was preserved by a well-known children's writer Sapargali Begalin. He had kept the clippings of the poem's text hidden in his down pillow for 20 years. It is said that when contemporaries and well-wishers of the poet learned that "Qulager" had been found, they were so delighted by the news that they marked the occasion with special recognition.

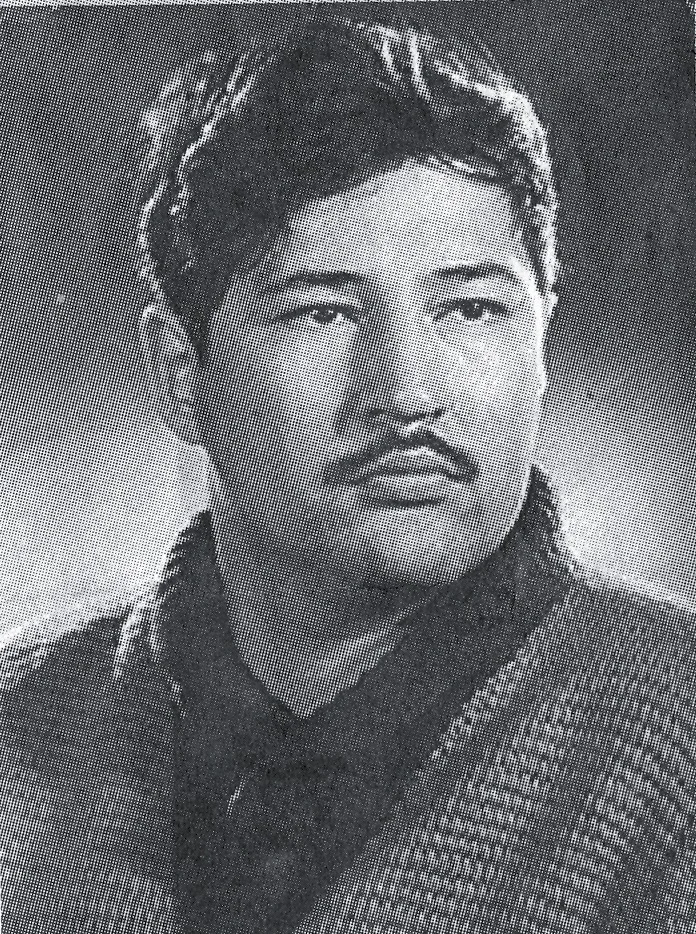

Photo of Ilyas Zhansugurov taken during the arrest of the NKVD/From open sourcess

THE LAST UNCERTAINTY: "IT TURNS OUT ILYAS IS NOT DEAD, HE IS ALIVE"

People do not want to believe in the death of their beloved sons. To this day, there are legends about the Alash Orda members, claiming that Bauyrzhan Momyshuly saw Magjan Jumabayev in Magadan and that Mirjakyp Dulatov lived in Mongolia. A similar legend exists about Ilyas. This belief was fueled by Fatima Gabitova, who never ceased searching for her husband after his arrest.

One day, Fatima, who had been writing letters to the NKVD prison in Almaty in search of her husband, received a response from one of the prison staff: "Your husband is far away. He has been exiled to Siberia."

According to the memories of Ilfa Ilyasovna, in 1955, an unknown man came to their home and told her mother: "Your husband is alive, I was in prison with him. He will return soon." Hearing this news, they surrounded him with attention and care, bought him clothes, and created all the conditions for him to feel comfortable. After a few days, they showed him photographs of Ilyas Jansugurov and Bilyal Suleyev hanging on the wall and asked: "With whom of them were you in prison?" He pointed to the photo of Suleyev. Distrust settled in their hearts, and they eventually drove the man away. This legend also reached Ilyas' native village. His brother Bimaghzum gave away his horse to people who brought him the joyful news that "it turns out, Ilyas is not dead, he is alive."

Bilal Suleev/personal archive of Eldos Toktarbai/Alash Electronic Library

The Ilyas Jansugurov Museum houses two certificates regarding the poet's death. The first one states the date of his death as February 26, 1938, and was issued by the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union on April 12, 1957. There is also a second certificate with similar content, issued on May 29, 1957, by Branch No. 2 of the People's Court of the city of Almaty. This certificate indicates that Ilyas Jansugurov died on April 29, 1949.

This information, of course, leaves Ilyas's children highly confused. Additionally, the claim by the "stranger," who asserted that he had come from Siberia, further complicates matters. Scholars specializing in Ilyas Jansugurov's life and work finally determined, based on the certificate from Moscow, that the Almaty court had made an error. However, it is said that Fatima believed Ilyas was alive until her death. The legendary figure was exonerated in 1957 due to the absence of a crime. It is known that even those who had written denunciations against him actively participated in his exoneration.

It is impossible to fully encompass the work of this poet, writer, translator, dramatist, public, and state figure. His works for children are a separate topic for study. Moreover, his work in collecting Kazakh küis and songs, as well as folklore, is simply colossal. Thus, herein, we have reviewed only a few of the most important aspects of the writer's life.

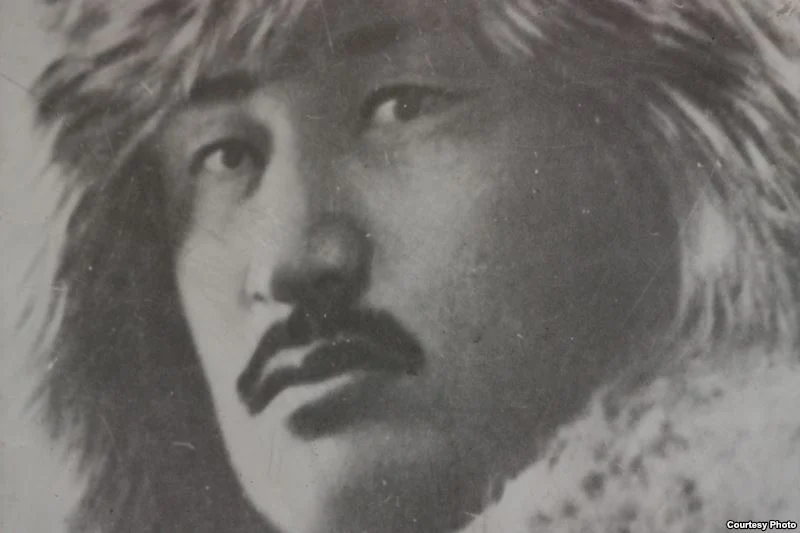

Ilyas Zhansugurov/From open sources