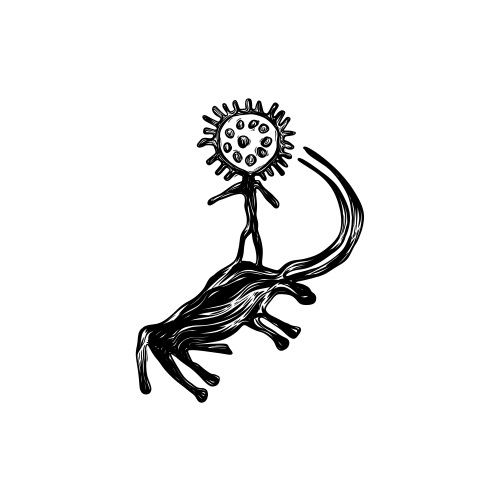

The Enigmatic Wheel

A Petroglyph Puzzle with a Twist!

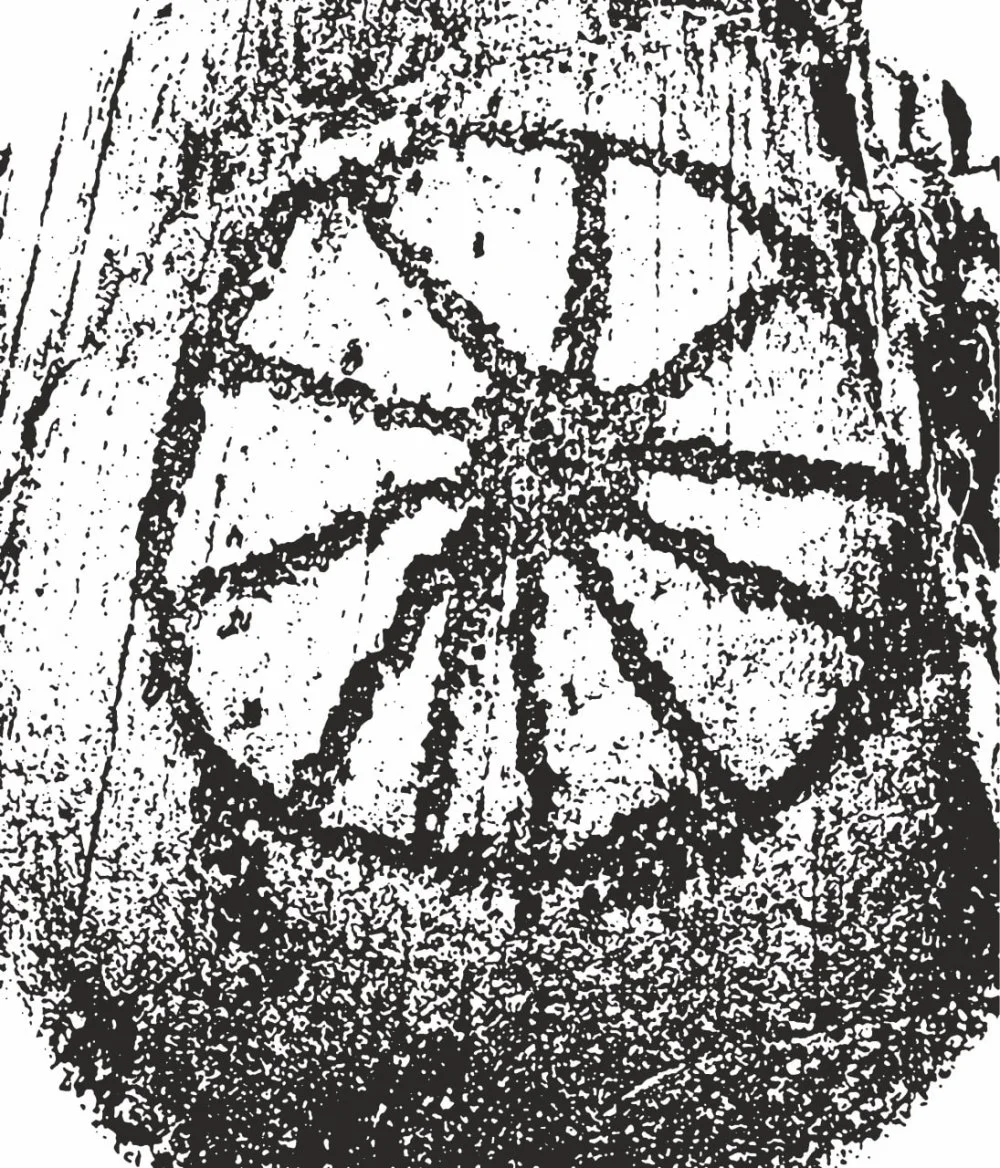

Wheel-sun. Fragment. Kulzhabasy/Olga Gumirova

‘With twelve spokes—it never wears out!—

The wheel of law spins across the sky.

Upon it, O Agnii

Seven hundred and twenty sons.’

This riddle, over 3,500 years old, appears in the Rigveda, the oldest known Indian texts in Vedic Sanskrit. Composed in all likelihood around 1700–1100 BCE, the Rigveda is one of the oldest Indo-Aryan texts and among the world’s earliest religious scriptures.

The answer to the riddle is clear—the writer talking about the year, and the wheel, of course, represents the sun. The mention of sons, totaling 720, might be puzzling, but with a bit of reasoning, it becomes clear that it refers to not only the days but also the nights of the year, which may come as a surprise to modern readers. Indeed, the ancient Indo-Aryans divided the year into 360 days and 360 nights.

Wheel-sun. Fragment. Kulzhabasy/Olga Gumirova

The wheel is one of the most frequently encountered symbols in Bronze Age petroglyphs, appearing in various clusters across Kazakhstan. In the religious worldview of ancient peoples, the wheel, symbolizing the eternal and mighty sun, played an important role, reflecting their understanding of the world’s structure and humanity's place within it.

A depiction of the wheel can be found among the petroglyphs of Quljabasy in the Jambyl region. Train travelers passing by Arqarly Station may have yet to learn that on a low ridge of the Chu-Ili Mountains, just east of the station, lies one of the largest petroglyph sites not just in Kazakhstan but in all of Eurasia.

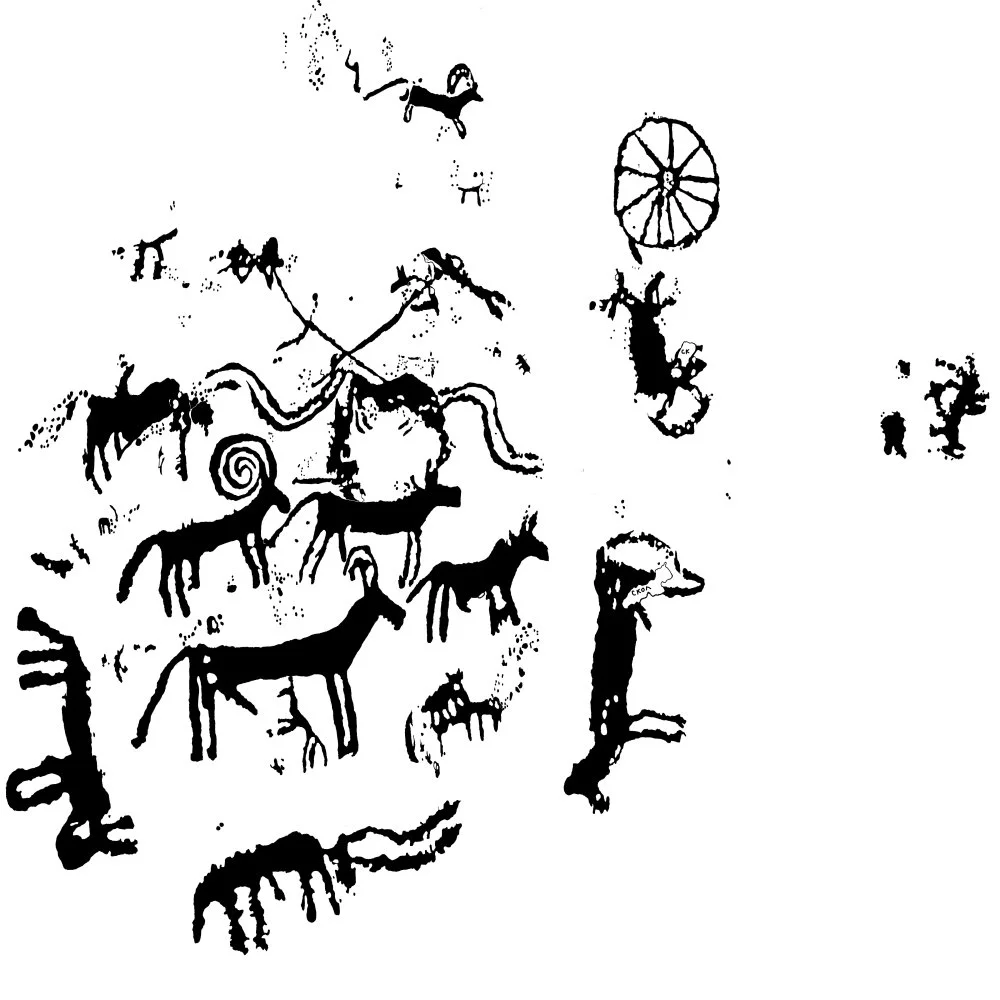

Zoomorphic scene with a wheel. Kulzhabasy/Olga Gumirova

Deep in the gorges, on sun-scorched hilltops, entire galleries of ancient rock art lie hidden, and among these is a scene depicting a wheel. The surface is heavily patinated, making it challenging to find without knowing its exact location. In addition, the details of the image can only be seen in oblique light, usually right before sunset.

The wheel in this petroglyph has eleven spokes, not twelve as in the riddle, but the carving dates to around the same period as the verse from the Rigveda. The specific tribe to which these artists belonged remains unknown, as research at the Quljabasy archeological complex is still ongoing, and no large-scale excavations of the settlements or burial grounds have been conducted yet. However, scientists speculate that the Andronovo tribes were likely involved in the creation of this sanctuary.

Landscape/Olga Gumirova

Perhaps the exact number of spokes in a wheel wasn't critically important to the shaman artists, but we should note that the four spokes in the wheels of a chariot from the same petroglyph cluster are carefully aligned with the cardinal directions. At that time, it was commonly believed that the sun made a daily journey in a chariot drawn by horses, appearing and disappearing at precisely fixed points on the horizon. For the ancient inhabitants of the Chu-Ili Mountains, this knowledge seems to have been more significant.

So, why are there eleven spokes? It’s easy to assume it was a slip by the artist, but it’s also possible that this is evidence of an unknown calendar system. Ancient cultures often divided the year in ways unfamiliar to us—Britain's ancient inhabitants, for example, divided the year into thirteen months, while the Mesoamericans had a calendar with only 260 days in a year. Could the spokes hint at a forgotten way of marking time? We do not yet know the answer, but perhaps it would be a worthy endeavor to explore ancient timekeeping further.

Horses graze in the Chu Ili Mountains/Olga Gumirova