White innocence

A Review of Michel Pastoureau’s White: The History of a Color

Viktor Vasnetsov. "Warriors of the Apocalypse". 1887/Wikimedia Commons

The acclaimed series of books The History of a Color (comprising the titles Black, Blue, Green, Red, Yellow, and White) by the French historian, medievalist, and heraldist Michel Pastoureau, holder of honorary titles and winner of prestigious awards, is dedicated to the meaning of different colors in European culture, a subject that is little explored but certainly one of interest to even non-academics. It is a fascinating read that will help us not only to immerse ourselves in a world of curious historical facts but also reflect on the human capacity to see and recognize reality around us.

The sixth and, according to the author, final volume of The History of a Color is devoted to white and its history and symbolism in European culture. It is worth specifying that the book covers the significance of the color only and exclusively in European culture from ancient Greece to the present day. You will not learn anything from this book about the symbolism of white in Islam or in the cultures of the Far East, Japan, or India. Additionally, the symbolism of color, specifically white, in the pre-Christian cultures of Europe (with the exception of classical antiquity) is very poorly covered. Now, this study does not pretend to be comprehensive. The author writes about what he knows—and he knows a lot—so for readers interested in the subject, White: The History of a Color will undoubtedly be interesting and useful.

Still, this is perhaps the most uneven and controversial of all the books in the series. For example, literally from the first lines, the author is confronted with two essential questions: whether white is a color and what the difference between white and transparent is. I should note that it is impossible to resolve these questions without venturing into the realm of the natural sciences, which Pastoureau resolutely refuses to do. ‘The colors of the physicist, chemist, or neurologist are not those of the historian, sociologist, or anthropologist. For these latter disciplines—and more generally for all the human sciences—color is defined and studied first as a social phenomenon. More than nature, the eye, or the brain, it is society that “makes” color, that gives it its definitions and meanings, that articulates its codes and values, that controls its uses and determines its stakes. The issues it raises are always cultural,’ he writes. But in the realm of natural science, the questions that plague him are solved so easily that the author's arguments are almost funny. It is as if a linguist or anthropologist decided to answer the question ‘Why do trees sway?’ without even entering the realm of physics with a timid ‘Because the wind blows.’

French edition of Michel Pastoureau's book

All Pastoureau can do here is accept two axiomatic statements, ‘White is a color’ and ‘Colorless and white are two different colors’, and periodically remind the forgetful reader about them. How much easier it would have been for the author if he had at least taken into account the fact that Newton used daylight, that is, transparent, colorless light and not white light in his experiments on refraction! White is not a mixture of all possible colors but a separate, independent color. I realized this in kindergarten when, after being told the story of refraction, I tried diligently to produce white by mixing all the colors in a row, until I realized that even if there were a million shades in my box of watercolors, white would not result from mixing them. Be that as it may, the statements about both the chromatic nature of white and the essential difference between white and colorless are absolutely true, and there is no need to argue with the author. One could argue with his other theory, though: ‘My last remark relates to the symbolism of colors. Colors are always ambivalent, each possessing its positive and negative aspects… In the case of white, however, its symbolism is less dualistic. Most of the ideas associated with white are virtues or good qualities: purity, virginity, innocence, wisdom, peace, goodness, cleanliness. We could add social power and elegance… For a long time as well, white was the color of hygiene…’

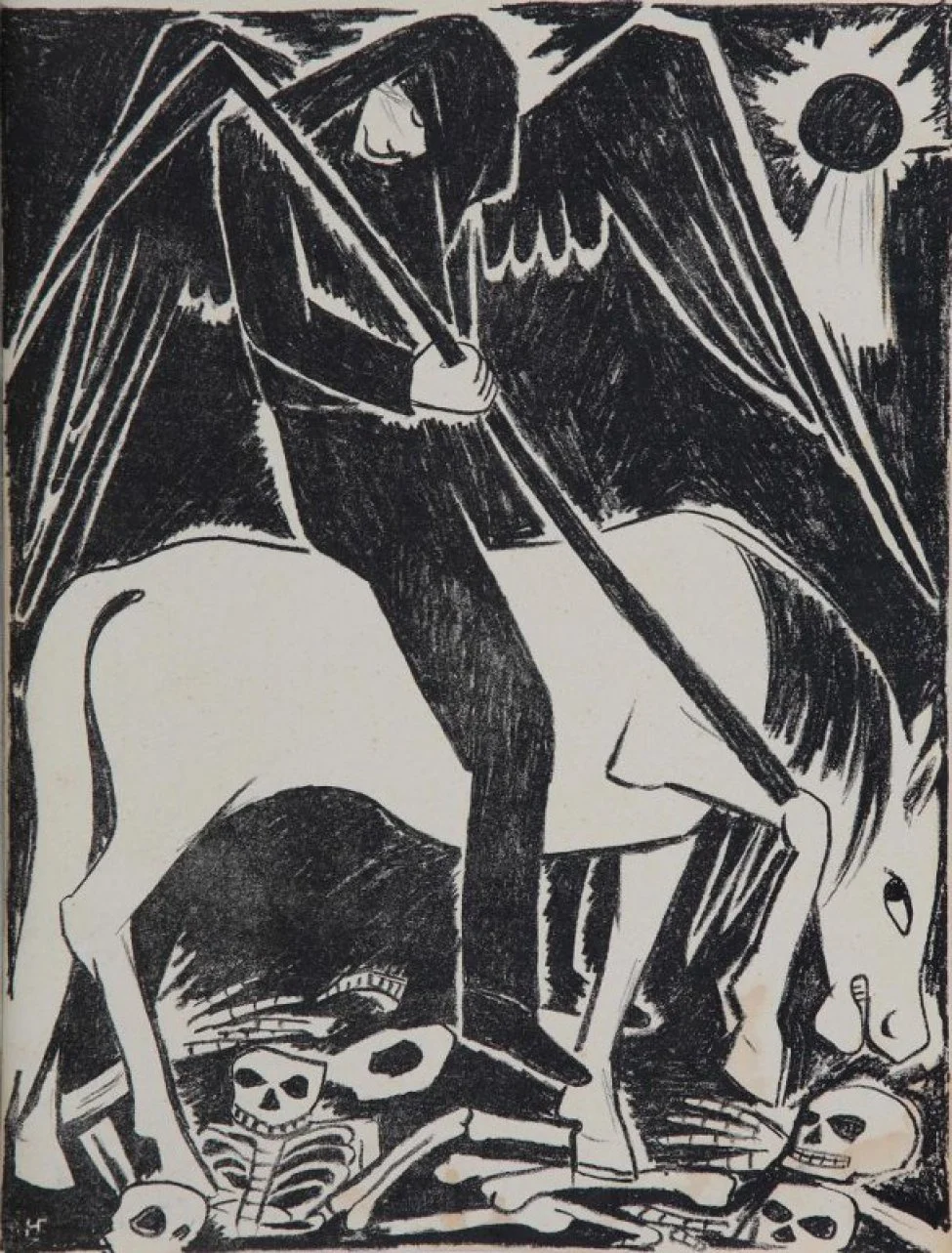

Later on, one gets the impression that the author, being overly preoccupied with the positive aspects of the symbolism of white, simply turns a blind eye to its negative aspects. This occurs to such an extent that in the sections devoted to the color white in the Old and New Testaments, Pastoureau does not even mention a part of the Book of Revelation that anyone who is even superficially familiar with the Revelation of John the Theologian remembers. It is about the opening of the seals and the appearance of the horsemen. Two of the four horsemen, carrying different plagues, ride on white horses of different hues: Pestilence (or the Conqueror), who leads this dark procession, rides on a white horse, and Death, who completes it, rides on a pale horse. One cannot say that the author is not at all familiar with the Book of Revelation. He writes: ‘Likewise in the Book of Revelation, where the color white, the color of victory and justice, occupies a dominant place, Christ rides a white horse and the celestial armies that follow him ride white horses as well (Revelation 19:11–16). This resplendent white is also the color … of the lamb and the garments of the twenty-four elders mentioned in Revelation (Revelation 4:4).’ The author seems to like to mention what correlates with his theory of the exclusively positive meaning of white!

Pastoureau completely ignores the theme of white as a representation of mortal pallor, and it is not only in this case. For example, he speculates on the meaning of white paintings on the body or face applied by primitive people: ‘[White body paints] served as protection against the sun, diseases, insects, and even forces of evil. But no doubt, in combination with or contrast to other colors, white had a taxonomic function as well: perhaps to distinguish groups or clans, establish hierarchies, mark points in time or rituals, and possibly differentiate gender and age groups.’ Notice that he does not even mention the subject of battle coloring, which is well known from observations of the lives of primitive tribes in Africa or America, where white was often used to make the face resemble a skull and thus frighten the enemy. But no! How could the beautiful, pure white be frightening? Not for Pastoureau!

Maasai in ritual image /Alamy

For this author, even ‘[T]he moon is the white star par excellence, the one that allows us to see in the dark and that, like the color itself, is a source of life, knowledge, health, and peace.’ Health? Really? Of course, the belief that fevers and mental illnesses are connected to the moon can be explained by the later struggle of the Christian church against lunar cults, but it is unlikely that this belief would have endured without an older basis.

Pastoureau is much more confident in the realm of linguistics, though his excessive academic dryness is often not to his advantage. When he claims that modern languages have only one word for white, and even uses this to hypothesize that the ancient Greeks and Romans distinguished more shades of white than we do, he overlooks the obvious—that in the modern lexicon, the number of words for various shades of white (‘milky’, ‘chalky’, et cetera) are no less than in antiquity. It is enough to open the color catalog of any manufacturer of not only paints but also household goods—from fabrics to cars—to know this for fact. But such research must seem too humble to the venerable medievalist professor.

In his book, Michel Pastoureau devotes a great deal of space to the contrast between white and black and white and red. It is surprising that for such a long and detailed discussion of the opposition of these three primary colors, the author—who is French!—doesn't even mention Stendhal. At the same time, Pastoureau dwells at length on Le Conte du Graal by Chrétien de Troyes,1

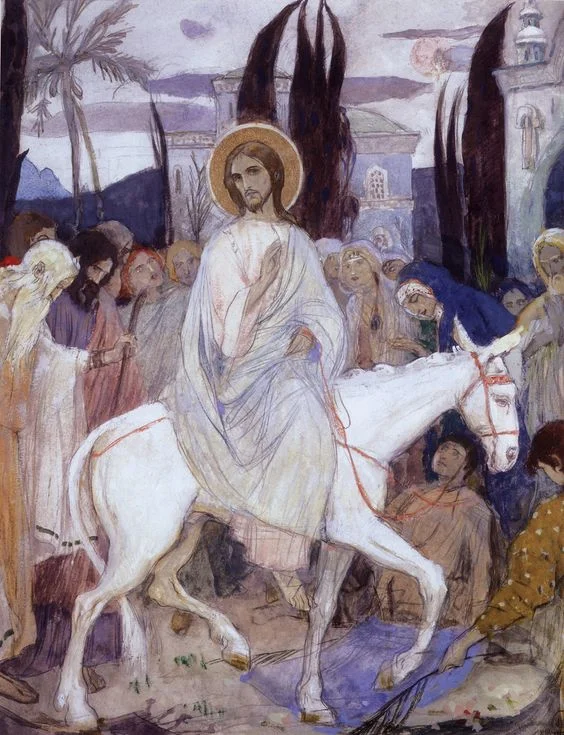

Mikhail Nesterov. "The Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem". 1900/Wikimedia Commons

Who knows, his reluctance to enter alien territory is maybe justified, but it makes it rather difficult to avoid mistakes and curiosities. For example, take this passage: ‘Among the ancients, admiration for the lily dates back very far. In various forms—true flower, simple floret, stylized plant motif—it can be seen on Mesopotamian cylinder seals, Egyptian bas-reliefs, Mycenaean pottery, Gallic coins, and Eastern fabrics. Not only does it play a decorative role, but it also often adds a strong symbolic dimension. Sometimes it is a matter of a nurturing fertility figure, sometimes a sign of purity or virginity, sometimes an attribute of power and sovereignty.’ I have a strong suspicion that Pastoureau sometimes confuses the image of the lily with that of the lotus, which is also a white but quite different flower, which was indeed an important symbol in ancient Egypt, India, and elsewhere.

I have long wondered what the white color on the flag of republican France means since white is the traditional color of the monarchy. Yes, I know that it is now generally believed that this color symbolizes equality (one of the components of the motto Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité), but this is clearly a late, modern interpretation since white never symbolized equality in the culture of the time. So what does it stand for on the flag? I expected to find the answer in this book—the author is French, after all! But I didn’t. Pastoureau describes the war of flags and cockades in great detail, but he manages to say not a word about the meaning of the three colors of the French Republic. Even if he considers it trivial and certainly common knowledge, it would have been worth mentioning at least briefly.

French flag on the facade of the old city hall building with the national motto "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity". Gravelines city /Alamy

And that, unfortunately, is not the only blank space (pardon the unintentional pun!) in the fascinating and informative book White: The History of a Color. After reading it, you will learn a lot of interesting and carefully selected facts, but do not forget that the author's interpretation of this information is, unfortunately, often flawed. Here's a simple example: ‘Many explanations have been offered for the origins of white clothing for tennis, golf, cricket, rowing, and other outdoor sports. The least fantastic finds the source in practices of the English aristocracy in the second half of the nineteenth century. Supposedly they chose white for summer sports because perspiration stains from physical exertion were less visible on it than on other colors.’ Anyone who has dealt with such stains will immediately object that wet stains are perfectly visible on white. However, the white powder of talcum, which has been used for centuries to prevent excessive perspiration, is almost invisible on white. I don’t know if that’s why they chose white sports uniforms, but it seems a lot more logical.

Pastoureau’s discussion of the black-and-white, contrasting world that he argues emerged with the invention of the printing press is in many ways valid, but even here there are some caveats. ‘In medieval handwritten books, the ink was never completely black and the parchment never white,’ he writes. How could paper be white after a few centuries? Pick up a book printed as recently as the middle of the last century; its yellowed pages were once bright white, too. We have no way of knowing how contrasting the text was in fresh medieval manuscripts. It is likely that the ink was as black as, well, ink—otherwise the language would hardly have retained this construction.

Let’s not forget that printing opened up the exhilarating black-and-white world of print to a tiny percentage of people—those who could read. In France, 50 per cent of the population did not learn to read until the last two decades of the eighteenth century, and universal literacy was still a long way off. Yet, Pastoureau writes with confidence: ‘The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries witnessed the progressive establishment of a kind of black-and-white world, first located on the margins of the color universe, then outside that universe, and finally, in direct opposition to it.

Natalia Goncharova. Illustration from "Mystical images of war". Kon' Bled (The Pale Horse). 1914/Wikimedia Commons

These slow and extended changes—taking place over two centuries—began with the appearance of printing in the 1450s and achieved their outcome symbolically in 1665–66 when Isaac Newton carried out new experiments with glass prisms and broke down the white light of the sun into colored rays.’ But were there many people who tapped into the life-giving source of printed books in the middle of the fifteenth century? I do not ask how many people even knew about Newton's discovery of the dispersion of light before the introduction of universal secondary education. The vast majority of people lived serenely for centuries without even knowing about the alleged revolution in color perception.

I don’t want you to think that Michel Pastoureau’s book is bad after reading this short review. On the contrary, any book that makes you think, agree, or argue is good, especially such a treasure trove of facts, from the common to the obscure, offered to us by a distinguished medievalist professor. I’d be happy if you’d read it and make up your own mind.

What to read

Pastoureau, Michel. White: The History of a Color. Translated by Jody Gladding. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023.