Prussian Blue

The Story of How Two Con Men Gave the Gift of the Sky to the Impressionists

Edvard Munch. Starry Night/Wikimedia Commons

From the vibrant swirls of Van Gogh's The Starry Night to the haunting depths of Hokusai's The Great Wave off Kanagawa, Prussian blue has long captivated artists’ imaginations. But the story of this color spreads far beyond the canvas. It's a tale of accidental invention, artistic revolution, and acts of Nazi atrocity that would forever complicate this seemingly innocent hue. Let's dive straight in because the history of Prussian blue is as unexpected as the color itself.

A Rather Fortunate Act of Fraud

The story begins in 1706 when Johann Jacob Diesbach, a Berlin-based color maker, ran out of potash, an agent he would add to cochineal extract to create red paint. He decided to replenish his stock from Johann Konrad Dippel, an alchemist. Dippel did not have any good quality potash, and he shamelessly sold Diesbach some that had already been used for clarifying bone oil. At the time, bone oil was considered the best remedy for aching joints, and the potash was therefore contaminated.

Much to Dippel’s surprise, when Diesbach reappeared demanding to know what he had been sold, he was far from angry—rather, he appeared ecstatic! And there was a very good reason for this reaction. Instead of the expected red, his retort contained a sediment of that amazing blue color that artists had, over many, many years, tried and failed to achieve in their paintings, as it could not be achieved by using lapis lazuli, or azurite, or cobalt, or vegetable dyes.

The trail of what happened to Diesbach, who was so fortunately conned, goes cold, and it is not known if he ever managed to make any profit from his accidental discovery.

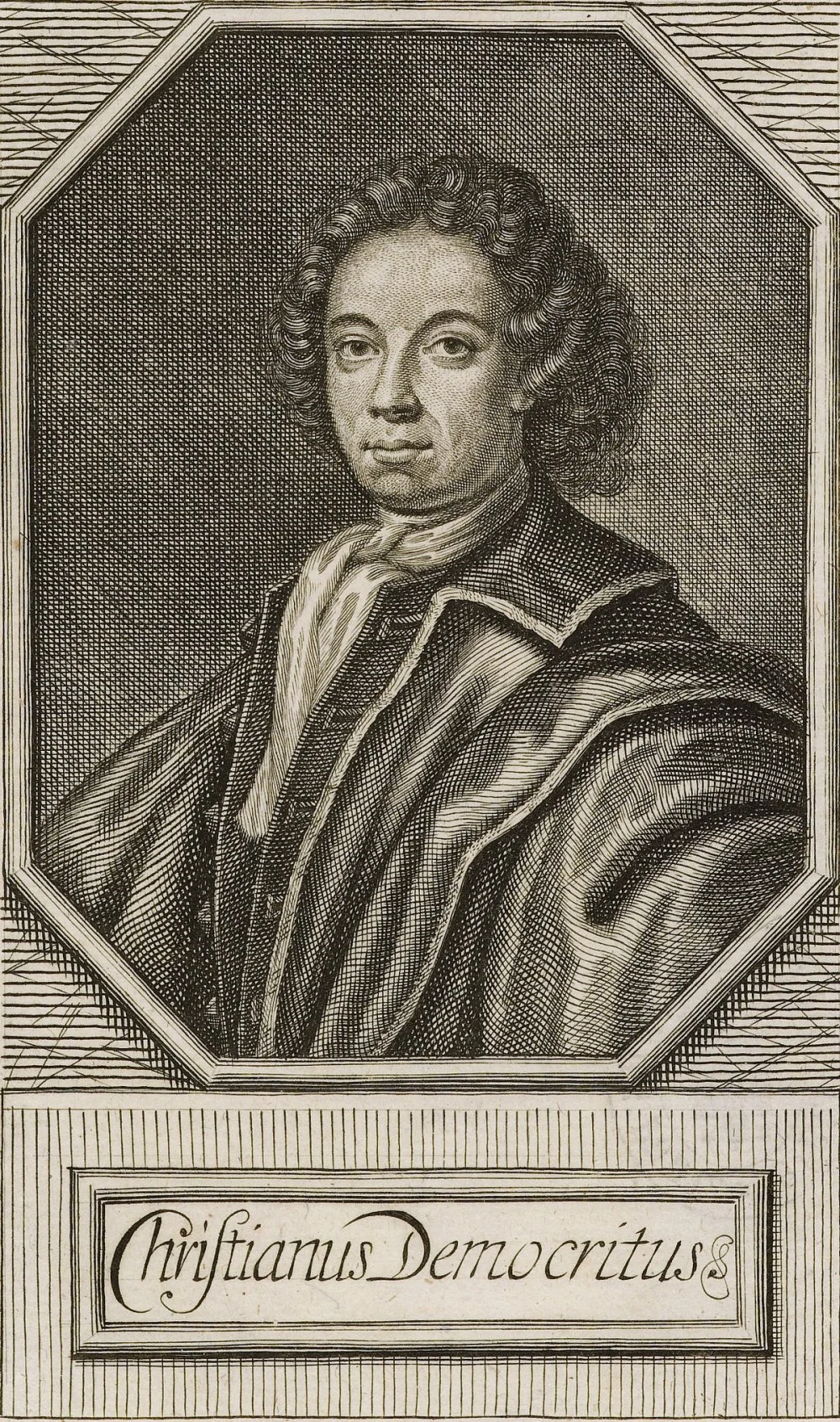

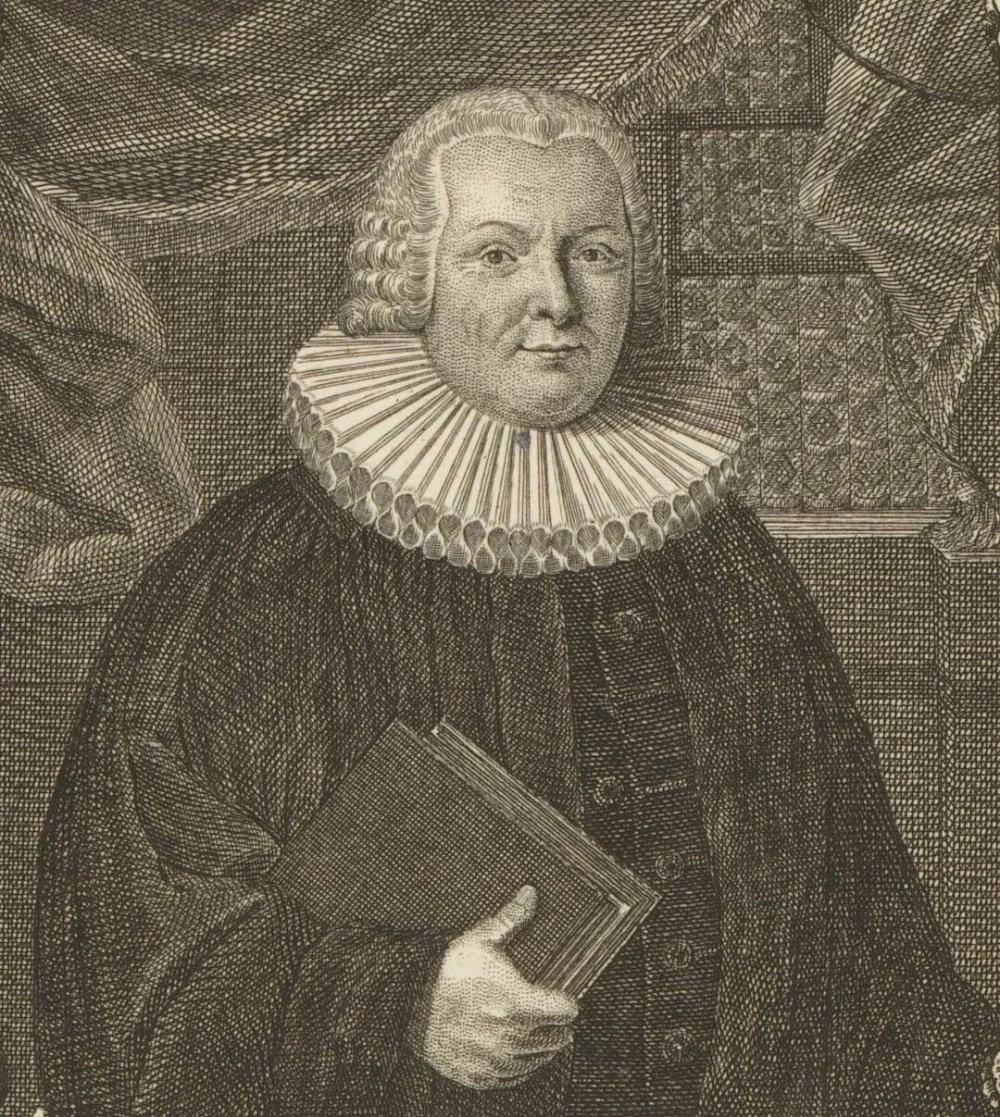

Johann Konrad Dippel/Wikimedia Commons

Theologist, Alchemist, and Con Man № 1

However, Dippel, a schemer and a brazen opportunist, immediately recognized the potential benefits of this discovery. According to one version of events, he became the prototype of Victor Frankenstein from the famous novel by Mary Shelley. This connection is fueled by Dippel's reported addition of ‘von Frankenstein’ to his surname, mimicking the nobility of the day. It should also be noted that the idea that he was born in the famous castle and belonged to the Frankenstein family was one he had propagated himself. And so, the newly christened Frankenstein, having got his hands on the color blue that had never been seen before, abandoned his main project, trying to create the elixir of life. Instead, he prioritized the newfound Prussian blue. He guarded the recipe fiercely, transforming himself into a shrewd businessman.

Over the next decade, he amassed a fortune by selling this captivating pigment to artists and dyers across Europe. During this time, he managed to move to the Netherlands, gain a diploma as a doctor of medicine, become an honorary physician to Frederick I, king of Sweden, kill several patients with his medicines, and end up in a Danish prison for his part in political schemes. However, Prussian blue remained Dippel’s biggest achievement. He never managed to create his own monster using parts of cadavers or transfer a soul from one body to another using a funnel, a hose, and lubricant.

Prussian blue pigment/Shutterstock

Con Man № 2

Dippel, despite being a con artist, didn’t manage to pocket all of the profits from the discovery of Prussian blue. He studied theology, philosophy, and alchemy, but to fully understand what was going on, he needed the help of a well-educated chemist. Dippel approached Professor Johann Frisch, the protégé of the great Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.i

Portrait of Johann Friedrich Frisch/Wikimedia Commons

The Unveiling of the Secret

For Dippel and Frisch, cash for the color did not keep pouring in for very long. In 1724, English scientist John Woodward received a letter from Germany describing the process of preparing Prussian blue. Woodward showed the letter to a member of the Royal Society, the chemist John Brown, who conducted some experiments to ensure the authenticity of the recipe. In the same year, Woodward and Brown published the secret of the famous dye in England’s main science magazine Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Almost immediately after this article was published, various manufacturers of Prussian blue started popping up all over Europe.

The pigment was initially called Preussisch blau, and in November 1709, it also acquired the name Berlinisch blau. Over the course of its history, it has been known by many names, including iron blue, Paris blue, and Prussian blue, as well as Hamburg blue, Turnbull’s blue, Milori blue, and neublau.

Thomas Gainsborough. The Blue Boy/Wikimedia Commons

The Sky and Sea of the Impressionists

Today, Pieter Van der Werff’s The Entombment of Christ (on display at the Sanssouci Picture Gallery in Potsdam) painted in 1709 is the oldest known painting that uses Prussian blue.

Historian Michel Pastoureau writes: ‘Contrary to the popular belief that quite possibly exists due to Dippel’s bad reputation, Prussian blue is not poisonous and does not turn into cyanide by itself. It does, however, get more pale if exposed to light and will disintegrate if in contact with alkali substances, which makes it incompatible with some paints bases. It does have a very high intensity color and when mixed with other pigments it gives amazingly beautiful and clear tones. This is why impressionists and other painters who were partial to plein-air painting had developed some sort of a cult of Prussian Blue, despite its high price and propensity to “run” when applied over other paints.’

Peter van der Werff. The Еntombment of Сhrist/Wikimedia Commons

Sinister Pigment

Berlin blue was not only famous for its beauty. In 1782, Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele used this paint to isolate cyanide (НСN,) and in 1811, a French chemist, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac, isolated HCN in gas form. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Berlin chemists used it as a base to create a pesticide under a trademark of Zyklon В, a notorious gas that was later used by the Nazis in gas chambers in their concentration camps. This is how the term ‘Berlin blue’ got another hidden and sinister meaning.

Edmund Rabe. Royal Prussian Infantry Officers/Wikimedia Commons