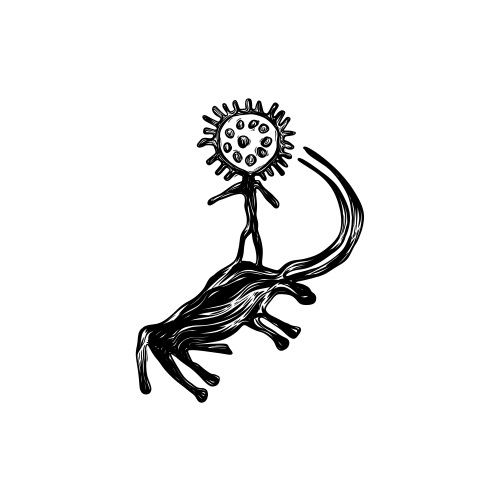

The World Tree

And horsewomen

The World Tree petroglyph/Olga Gumirova

In 2020, the Petroglyph Hunters team discovered a large cluster of petroglyphs on one of the peaks in the southern part of the Dauylbai Mountains in Jetisu. Despite this, the location lacks the ideal characteristics suited to rock art—there are no well-oriented, smooth rock surfaces, and the stones lack a distinct ‘sunburn’ patina. Yet, the location was so significant that everyone, from the shaman-artists of the Bronze Age to the Turks, have left their mark here. From this vantage point, one can see at least three sizable clusters of petroglyphs, each separated by a distance requiring one to two days of travel by caravan.

The repertoire of this small group of petroglyphs, located on what was once a bustling route (the uniqueness of the Dauylbai Range as an ancient transport hub lies in the fact that most paths run along the ridges rather than the valley floors), showcases quite a diverse range of images and includes several cult scenes. Most of the rock art at this location dates back to the Bronze Age. One particular petroglyph stands out as especially significant. It appears to depict the world tree with horse riders positioned on either side. Surrounding the central image of the tree are several indistinct figures of horned goats arranged in a circular pattern, which is a clear representation of solar symbolism. An additional goat figure is shown in a posture suggestive of ritual sacrifice.

The world tree is one of the most universal mythopoetic symbols, embodying the structure, essence and concept of the world across numerous ancient cultures. The tree's roots are usually associated with the lower, underground world of ancestral spirits. The trunk corresponds to the world of humans, while the tree's crown, with its spreading branches and leaves, represents the dwelling place of gods and spirits, including the spirits of one’s ancestral lineage. This motif is found across various tribes and peoples across the world, not only in their oral traditions and religious beliefs but also in their visual art including petroglyphs.

One particular group of drawings features symmetrical depictions of hoofed animals or human figures (gods, mythological characters, priests, or people) on either side of the world tree’s trunk. According to scholars and ethnographers, such scenes reflect the transition from the old year to the new one, which in ancient times was associated either with the equinox or the days of the summer or winter solstice.

So what information did the shaman-artists encode into the scene from Ordakul? To find the answer, let's turn to traditional northern Russian paintings and embroideries, whose symbolic elements and their meanings have been preserved thanks to the work of past ethnographers.

It might seem as if the Dauylbai Range in Jetisu and the Russian North are separated by thousands of kilometers, and these images are divided not just by centuries but by millennia.

In traditional Russian folk art, particularly from the northern regions (Arkhangelsk, northern Dvina, Vologda, et cetera), horses usually symbolized the sun and were frequently portrayed with riders, the goddesses of spring. The art historian G.S. Maslova refers to the intricate ornamentation featuring two symmetrical riders on horses facing the tree of life as the ‘meeting of spring’. The image of a priestess—whether a maiden or a young bride—riding a horse into a sacred grove, offering sacrificial gifts to the trees (and later circling the horse around a plowed field) is a common archetype across Eurasia and North Africa that emerged no later than the mid-fifth millennium BCE.

The final argument supporting this interpretation is that the slab with the petroglyphs is tilted westward, meaning that when it is viewed, the crown of the tree is directed toward the sunrise, most likely on the day of the spring equinox.