Magical Mola Tapestry

When Missionaries Confronted Bare Breasts

Dioscoro Puebla. "Columbus' landing in the Americas". Painting of 1862/Library of Congress

How Spanish colonization accidentally led to the emergence of a new art form—unique tapestries.

The Guna people (also spelled Kuna or Cuna) are descendants of the Muisca (Chibcha) civilization, which was one of the most advanced in South America, comparable to the Mayans, Incas, and Aztecs. The Muisca culture reached its peak between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, when their population exceeded a million people. They were talented jewelers and metallurgists, and their lands stretched over 25,000 square kilometers from the high plateau of the Eastern Cordillera to the Orinoco tributaries.

The Spanish conquest marked the end of the Muisca Empire, and today, their descendants, the indigenous Guna people, number around 50,000 and live in Colombia and Panama. The Guna people now live modestly, with the remnants of their ancestors' brilliant civilization—golden ornaments, utensils, and sculptures—now being found only in museums. However, the Guna invented something entirely new and perfected it—unique tapestries called molas.

Panama's handmade mola/Getty Images

The everyday female attire of the Guna emerged as a result of the infiltration of European lifestyles and the civilisational requirements of the new era into their culture. Earlier, Guna women decorated their bare shoulders and breasts with patterns made with colored paints. These were intended to protect the lady and her household from evil spirits and various disasters, but the missionaries insisted that the indigenous women should adhere to a modest appearance that followed Christian norms. Eventually, Guna women yielded to these strange demands and began wearing dresses in the European style, complete with corsets. All this new clothing came to be called by the old word ‘mola’, which in the Guna language meant ‘shirt’ or ‘cape’.

However, in the second half of the nineteenth century, Guna women began to modify European clothing according to their own notions of beauty and reason. The protective drawings that were previously applied to the naked body logically transitioned onto fabric, subsequently transforming from drawings into appliqué. Initially, patterns were part of the decorations of their clothing, embroidered and applied to corsets, but gradually the mola technique became an independent craft. Today, it is used to make clothes, blankets, and other decorative textiles, including wall tapestries.

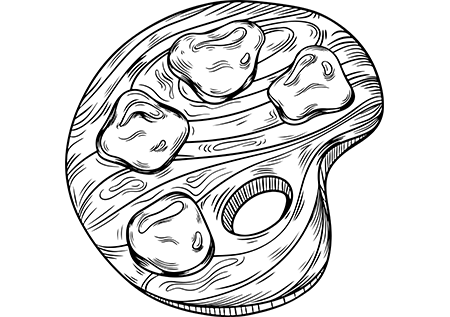

Upon a first, inattentive glance, a mola tapestry may seem like embroidery, but that's not the case. Upon closer inspection, it is clear how complex this almost three-dimensional construction is, executed in the technique of reverse appliqué. Each tapestry consists of several (usually two to seven) layers of colorful cotton. Small openings are cut in the upper layer, through which the next layer is revealed, and the next beneath it, and so on. As the layers go deeper, the cut-outs get smaller. The edges of the cut-outs are folded and sewn, and the entire construction is assembled with thousands of tiny stitches. To achieve a stronger artistic effect, additional embroidery is also sometimes done on top of this multilayer appliqué.

Owl design on tapestry/Getty Images

Even the simplest mola requires tens of hours of painstaking manual labor, but work on the most complex tapestries can take several months. Accordingly, the price of the tapestries varies. The simplest and most common tapestries with uncomplicated patterns usually consist of two layers of fabric and are made within a couple of weeks. Tapestries made of four layers and more, with original and truly complex appliqué, are rare and much more expensive. The price is also influenced by their quality. For example, in the most expensive molas, the stitches are so small that they are practically invisible. It is possible for a talented and hardworking craftswoman to earn decently by exclusively creating molas, but her work is, in modest terms, not easy.

The design of mola tapestries ranges from depicting simple geometric ones to detailed floral patterns and conceptual designs. Often, on these tapestries, one can see whimsical fish, turtles, and birds intertwining in an intricately arranged and vibrant space. The colors of the appliqués are always very bright and contrasted, with the composition being precisely balanced and involving endlessly varied plots.

Guna girl shows off colorful molas/Getty Images

The French ethnographer and anthropologist Michel Perrin, who studied the art of the Guna people and wrote the book Kuna Pictures: Molas, an Art of America (Tableaux Kuna: Les Molas, un art d'Amérique), played an important role in the popularization of mola tapestries. Nowadays, mola tapestries can be seen not only in street markets, for example, on the San Blas Islands in Panama, but also in private collections and museums worldwide.

However, in Panama and Colombia, even the finest molas can still be bought for the price of a couple of restaurant lunches. This craft is widely practiced by peasant women and women from the poorest layers of the population, who do not seem to know the real value of their work. Most of the craftswomen today are already elderly women; young girls usually do not see any special value in making molas and do not seek to adopt their grandmothers’ art, and there is a risk that the mola craft will gradually decline in the coming years.