Over the past 4,000 years, Syria has stood at the crossroads of civilization, a battleground for empires and conquerors. From the ancient Akkadian ruler Sargon to Alexander the Great, Syria has been a prize long-sought after. Today, this historically contested land still remains a focal point of global tensions, an undeniable sign of its enduring strategic and cultural significance.

In September 1260, at the spring of Ain Jalut in modern-day Israel, one of the most significant battles in medieval times took place, forever altering the history of the Middle East and the Mongol Empire. The aftermath marked a turning point, eventually leading to the distinct development of the Jochi Ulus, which would culminate in the creation of the Kazakh khanate two centuries later. Remarkably, both sides in this battle on ancient biblical lands were led by commanders of Central Asian descent: Mamluk emir Baybars, who would soon become the sultan of Egypt and Syria, and Kitbuqa, a Naiman general of the Mongol army. Both are familiar names to Kazakh readers, long celebrated in epics and films, yet they fought for Syria, which, after this battle, came under Mamluk control, although the Mongols continued their attempts to reclaim it for years.

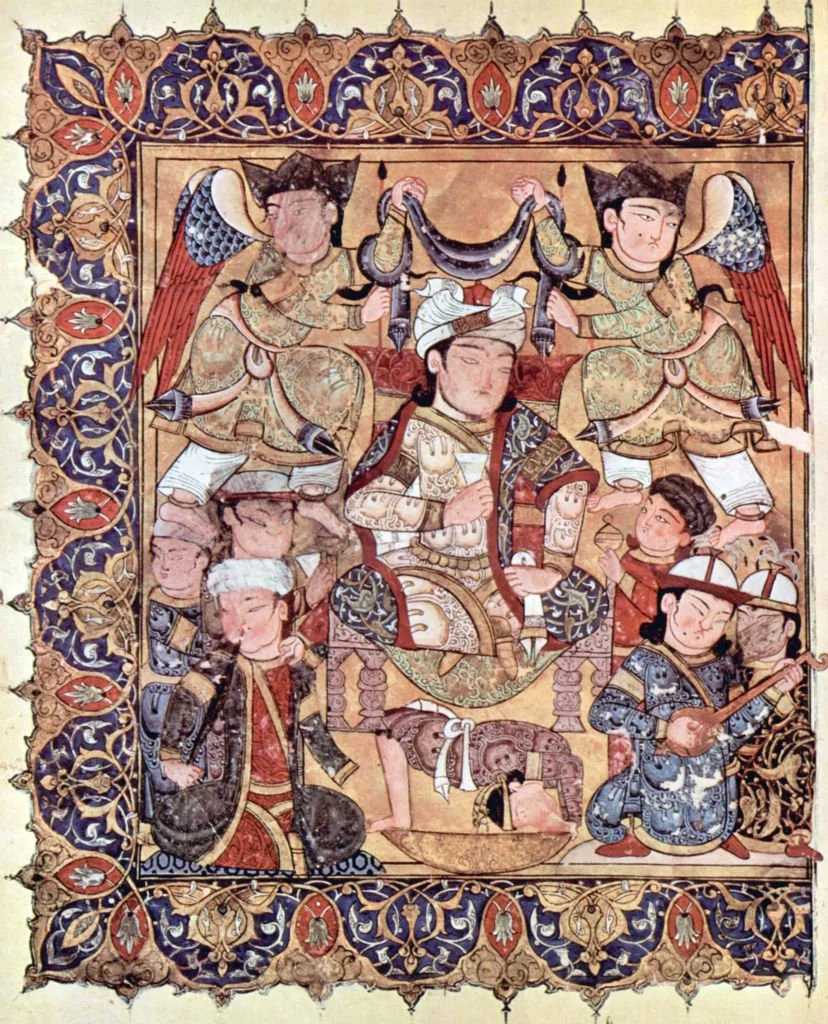

Sultan Baybars, Mamluk Sultan of Egypt. Frontispiece from an illustrated edition of Al-Hariri of Basra's Maqamat (Arabic tales told in rhymed prose) 1334/Pictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Shortly before this, Mongol forces under Hulagu Khan, the grandson of Chinggis Khan and founder of the Ilkhanid dynasty, captured the Syrian cities of Hama, Homs, Aleppo, and Damascus. This conquest brought down the once-great Ayyubid Empire, which had spread from Iran and Iraq to Egypt and Libya. At the time, its capital was located in Aleppo.

Salah ad-Din and Syria

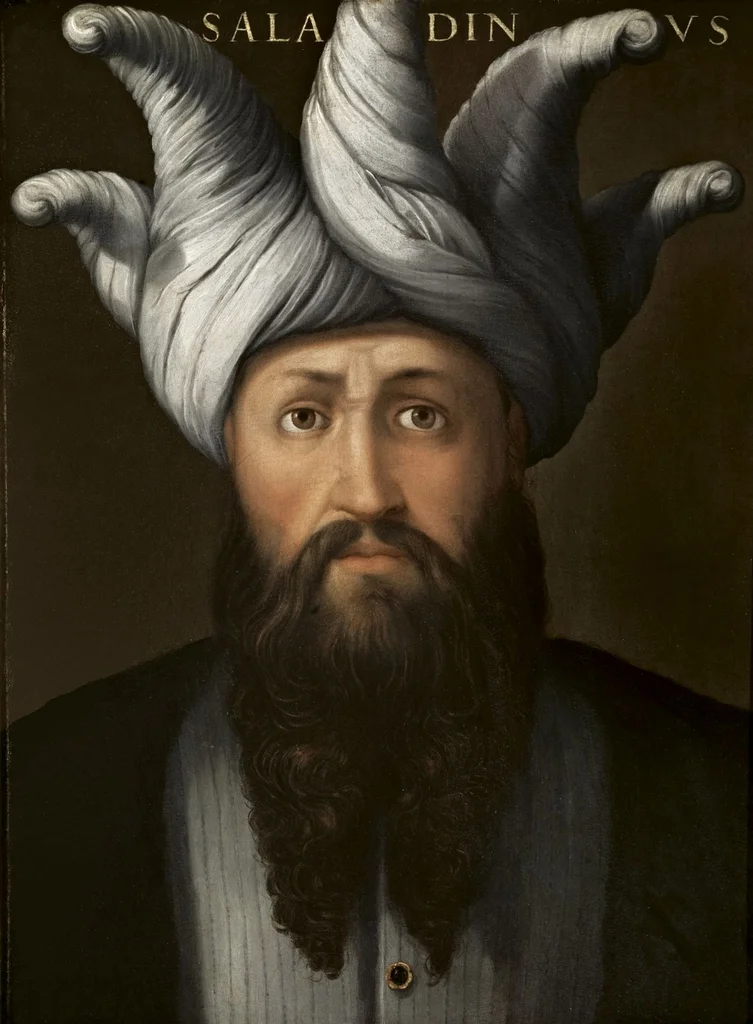

The Ayyubid dynasty's founder, Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, better known as Saladin, is a very widely recognized historical figure, famously depicted in Ridley Scott's epic drama Kingdom of Heaven. This reserved Kurdish general captured Jerusalem from the Crusaders in 1187, leading to the fall of the First Kingdom of Jerusalem and eventually to the Third Crusade.

Cristofano Dell'altissimo. Saladin. Before 1568/Wikimedia Commons

Before this, a devout Sunni himself, Saladin moved to Egypt to serve the last Shiite-Ismaili caliph of the Fatimid dynasty named after the Prophet Muhammad’s daughter. Rising quickly to the position of vizier, thanks to support from influential Syrian generals, he systematically curtailed the caliph's political influence, introduced Sunni practices, and suppressed Shiism. After the caliph’s death, whose authority had dwindled to a nominal status by then, Saladin proclaimed himself the ‘Sultan of Egypt’ and soon turned his sights on Syria.

Ayyubid Sultanate founded by Salah ad-Din/Wikimedia commons

Saladin captured most of Syria from the Zengid dynasty, warriors of Turkic origins, and ruled under the telling name ‘Atabegate of Mosul, Aleppo, and Damascus’. Following his conquest, the Abbasid caliph al-Mustadi granted Saladin the title ‘Sultan of Egypt and Syria’. This title would later attract the attention of the Mamluk Sultan Baybars, who would personally kill Turan-Shah, the last Ayyubid sultan of Egypt and Syria, even though it was the Ayyubids who had integrated the Mamluks, Turkic slave-warriors from the Eurasian steppes, into Egypt's military elite.

Syria in the 20th century

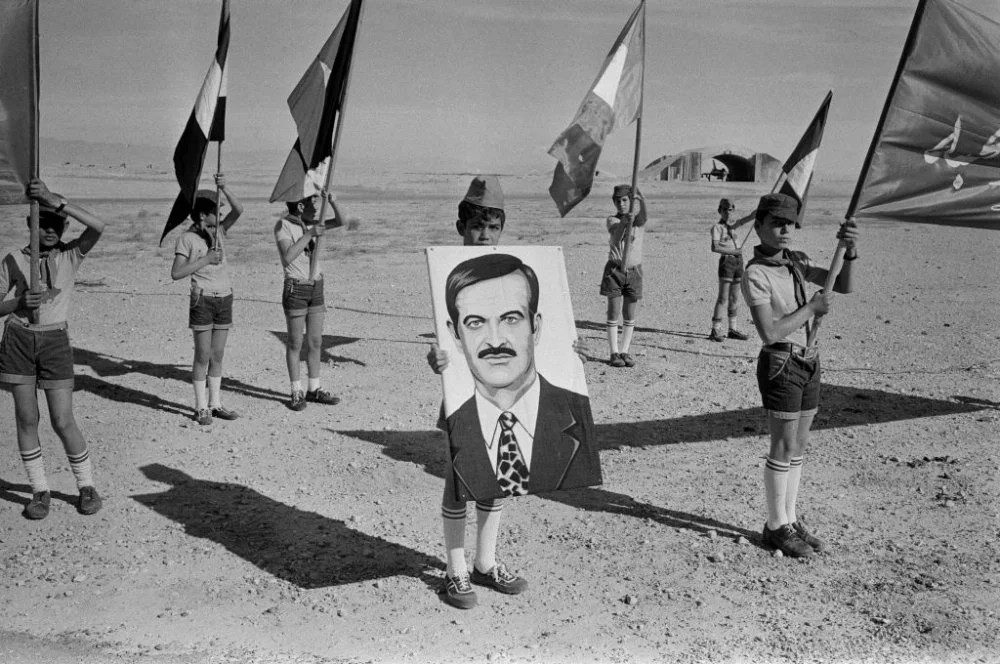

Power in Egypt then shifted to the Mamluk sultanate until the early sixteenth century, when the Ottoman sultan Selim the Grim seized Syria, followed by Egypt, once again uniting the two regions. Perhaps it is no surprise then that from 1958 to 1961, Syria and Egypt were briefly united to form the United Arab Republic. However, after a coup in Syria in 1961, the country left the union and formed the Syrian Arab Republic. Two years later, on 8 March 1963, another military coup shook the nation, orchestrated by three young Alawite officers, who at the time represented just over ten per cent of the population. The youngest and lowest-ranking among them was thirty-two-year-old Hafez al-Assad, who would overthrow his senior companions within seven years. For the next fifty-four years, the country would be ruled exclusively by his family, until the bloody regime of his son, Bashar, collapsed in a record eleven days.

Kids holding Hafez el-Assad’s photo/Photo by James Andanson/Sygma via Getty Images

A longstanding history of regime changes, ideological shifts, shifting borders, and ethnic, religious, and linguistic fragmentation—coupled with imperial ambitions—has been the norm in Syria for the past 4,000 years. Entire civilizations, not just political regimes, have risen and fallen, and Damascus alone has been conquered dozens of times.

Ancient Syria

As early as the third millennium BCE, Sargon of Akkad, the founder of the first empire in history, campaigned against Syria four times and finally incorporated it into his empire. By the second millennium BCE, the territory of modern Syria had become a battleground for the greatest ancient empires: Babylonia, Assyria, Egypt, and Persia. Approximately 3,000 years ago, Syria was conquered by the Assyrian Empire for three centuries, leading to the Greek-derived name for the region—Syria. Then, it was conquered by Babylonia, which later fell to the Persians, who were later defeated by Alexander the Great. After Alexander's death and the breaking up of his empire, Syria came under the rule of the Greek Seleucid dynasty, only to be conquered by the Romans, though it briefly became part of the Armenian kingdom of Tigranes I in the interim.

Roman theatre, built in the 2nd century AD in Palmyra/Giovanni Mereghetti/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Biblical Syria

Syria was also part of Canaan—a historic region inhabited by Semitic tribes—and the birthplace of the Phoenician civilization, with key city-states like Aleppo and Palmyra.

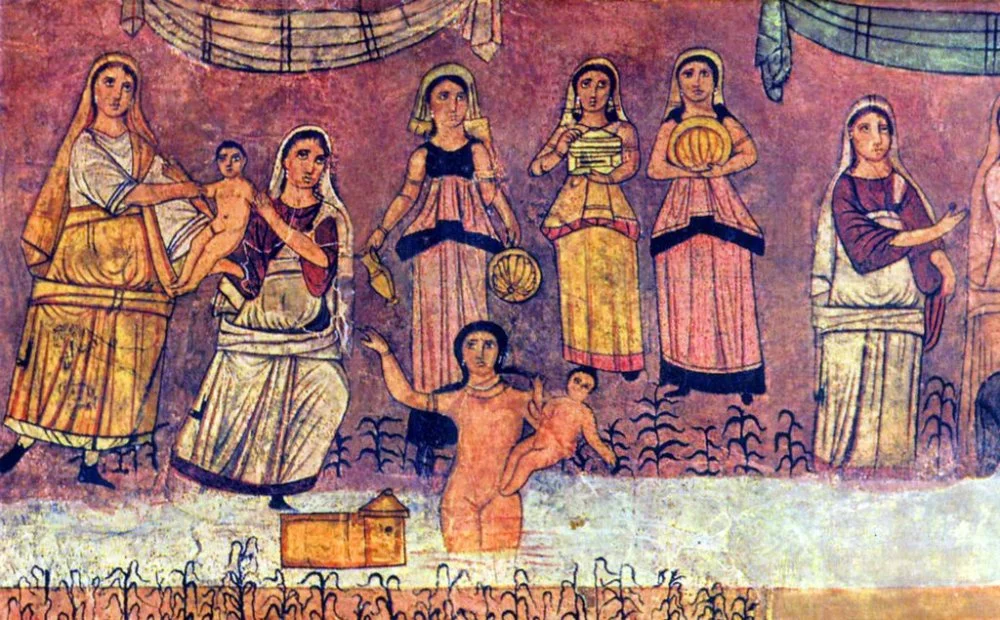

The childhood of Moses. Fresco from Dura Europos synagogue, c. 250 CE. Dura-Europos, Syria/Pictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Beyond Syria, Canaan included modern-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine. In the biblical tradition, part of Canaan is considered the ‘Promised Land’, the historical homeland of the Israelites, who journeyed there from Egypt. This began the Israelite conquest of Canaan and their ongoing struggle with the Philistines, another regional people whose name gave rise to the historical term ‘Palestine’.

Map of Canaan drawn in the 17th century/Wikimedia commons

Syria and the Arab Caliphate

From then on, religion began to play a central role in regional conflicts, heralding an era of ‘holy wars’. It is no surprise that Syria often found itself at the crossroads of crusades, battles between righteous and unrighteous caliphs and inter-religious and sectarian wars. Even in early Christianity, Syria was a hub for alternative Christian beliefs, including various Monophysite and non-Chalcedonian traditions. Nestorianism, founded by the Syrian theologian Nestorius, was declared heretical and banned, but it spread across Central Asia. The Mongol general Kitbuqa was, in fact, Nestorian.

Qal'at Siman or the Church of St. Simeon Stylites, one of the most revered Christian saints. 5th century AD. Aleppo, Syria. February 28, 2023/Abdulmonam Eassa/Getty Images

Syria also played a pivotal role in the schism of the Muslim world. After the death of Ali, the fourth ‘righteous caliph’, a bloody power struggle ensued, won by the governor of Syria, Muawiyah, who founded the Umayyad Caliphate with its capital in Damascus. Followers of Ali subsequently split from mainstream Muslims, giving rise to the Sunni (followers of the community) and Shia (followers of Ali) branches. As the name suggests, the Alawites, to which the Assad family belongs, are closely related to Shia Islam, although their inclusion in Islam is still debated due to practices like alcohol consumption during rituals, belief in reincarnation and a divine trinity, and more.

Crowds gather at Umayyad Mosque following the collapse of 61-year of Baath Party rule in Syria. December 8, 2024/Izettin Kasim/Anadolu via Getty Images

Syria between the world wars

Adding to this history are the 400 years Syria spent as a province of the Ottoman Empire, followed by its pivotal role in the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans during the First World War. While the Syrians joined the revolt in the hope of gaining independence, they ended up as a French mandate until the end of the Second World War instead. Making this betrayal worse was the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement, which arbitrarily divided former Ottoman provinces, including Syria, without considering ethno-religious and linguistic distinctions. All of these events have only fueled the nation’s current conflicts. And as if that weren’t enough, the creation of the pan-Arab socialist Ba'ath Party, which underpinned Hafez al-Assad's regime, aligned Syria with the Soviet Union during the Cold War, a relationship later continued by the Russian Federation.

In 1925, France put down a major uprising in Syria against the mandate. During the suppression of this uprising, Damascus was especially affected by artillery fire./Robert Sennecke/ullstein bild via Getty Images