Central Asia—the cradle of ancient traditions and a crossroads of diverse ideologies, cultures, and beliefs—has long captivated the imagination of travelers from near and far. Through their vivid notes and reflections, they offered, albeit not always impartially, a unique window into the rich mosaic of life in this region: bustling bazaars, nomadic customs, and an enduring cultural heritage. In this series of articles,

Qalam presents excerpts from their accounts and memoirs, spanning different eras and revealing the multifaceted nature of the region. Today, we present excerpts from various notes on how Kazakhs observed the sacred month of Ramadan in the nineteenth century.

Interestingly, travel notes from the second half of the nineteenth century sometimes present starkly contrasting observations on how Kazakhs observed the sacred month of Ramadan. For example, in Materials for the Geography and Statistics of Russia on the Kazakh Steppe, compiled by L. Meyer in 1865, Kazakhs were described as diligent in prayer but neglectful of fasting, or orazai

The prayers prescribed by the Muhammadan religion are performed quite diligently by the Kyrgyz, but fasting is rarely observed, especially among the common people, due to their innate gluttony. Of the prayers, the morning one at dawn and the evening one at sunset are considered the most important, while the others are observed less strictly. In general, although the Kyrgyz pray willingly, they have a pronounced aversion to mosques. This aversion was so strong that the late khan of the Inner Horde, Zhangir, resorted to rather severe measures to stir religious sentiment among the people: when the Kyrgyz gathered in large numbers at a fair held at his encampment, several mounted Russian Cossacks from the khan’s convoy would suddenly appear and drive the crowd into the mosque with whips.

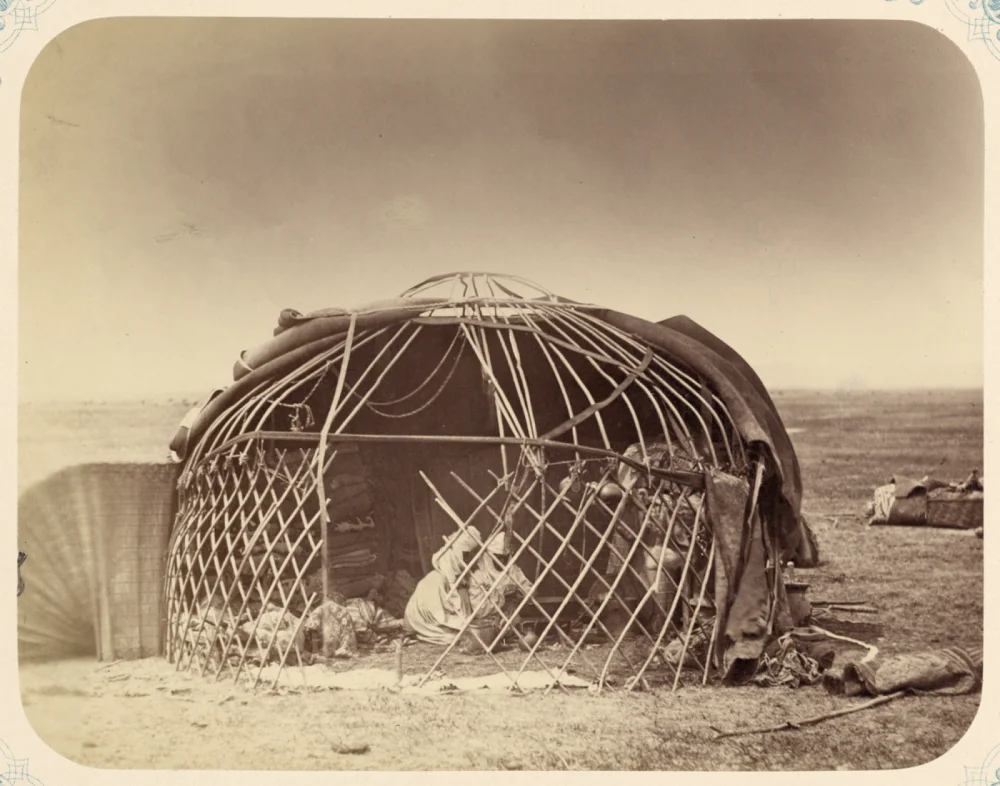

Kazakhs in yurt/Library of Congress

In contrast, the observations of Nikolai Frideriks in his Turkestan and Its Reforms: Notes of an Eyewitness (1869) present an entirely different picture. According to his account, Kazakhs diligently adhered to the rules of fasting, even in cases where it was not obligatory due to travel:

The Kyrgyz of the Greater Horde are more devout Muslims than many Russians assume. True, they do not read the Quran, as almost all of them are illiterate, but they faithfully observe holidays and fasts. More than once, at sunset, we witnessed entire groups kneeling in prayer, stroking their faces and beards, and bowing to the ground. Throughout the whole fasting month of Uraza (Ramadan), nearly all Kyrgyz—exceptions were extremely rare—abstained from any food or even a sip of water until evening. The Quran permits travelers to forgo fasting, yet the Kyrgyz who accompanied us, despite the cold, fasted strictly until sunset. Often, poor villagers, summoned by the commission from fifteen versts away, would return home in the evening at their usual slow pace (for in winter, the horses were thin and weak) and, by all accounts, could arrive well after sunset. And in the yurts during winter, only the wealthiest had qazy [a traditional sausage-like food in various Central Asian countries] and smoked mutton to add to the kazan [a type of large cooking pot used throughout Central Asia], where köje simmered—a simple dish of water and millet, prepared by roasting the grains and then pounding them in a mortar.

Kazakh communities in the nineteenth century greatly enjoyed celebrating Oraz Ait—the festival marking the end of fasting—often postponing other events to coincide with these festivities. Fok describes this in his Notes on the Nature and Productivity of Countries and Peoples: From the Urals to the Eastern Ocean, Based on Personal Observations and Research (1866):

They love festivities: after the Ramadan fast, which, in fact, differs little from their everyday life, they gather to celebrate at the home of a wealthy sultan. They celebrate weddings, annual memorials for the eldest in the clan, visits to distinguished individuals, and generally never miss an opportunity for a celebration.

In poor auls, festivities are limited to slaughtering a ram and engaging in gymnastic exercises. When I happened to visit a modest aul, the elder bustled about and sent for everyone to gather.