Interestingly, the title of the greatest sumo wrestler belonged first to a Ukrainian, then later to a Mongolian. Over the years, Hawaiians, and even a Georgian, have aspired to reach such heights. And who knows what the future holds? Perhaps one day a Kazakh will rise to become the next hero of this ancient sport.

On 29 January 2015, Japan’s oldest and largest English-language newspaper, The Japan Times, which has been in continuous publication since the late nineteenth century, came out with a rather insulting but unambiguously grim headline: ‘Hakuhō Leads Sumo’s Mongolian Invasion.’ Non-Japanese readers may require a clarification here. Hakuhō is a sumo wrestler of Mongolian heritage. At that time, aged twenty-nine, he had held the highest rank in sumo, known as yokozuna, for more than seven years—a distinction achieved by only seventy-three wrestlers in the sport's history. By winning the 2015 New Year Grand Sumo Tournament without losing a single fight, he achieved the impressive feat of his thirty-third championship.i

The expression ‘Mongolian invasion’ used by The Japan Times in its lamentation might also need clarification. It is perhaps the most glorious of the ideological themes of Japanese patriotism in 750 years. It is about the failed sea campaign of the Mongol army in the thirteenth century. Its failure is traditionally associated with divine intervention, with the god of the wind who created the kamikaze (meaning ‘divine wind’ in Japanese) who twice sank the Mongol armada. We are familiar with the kamikazes of the Second World War, suicide pilots who, according to Japanese commanders, were supposed to disrupt the enemy’s advance like the ‘divine wind’ of the thirteenth century.

Japanese sumo wrestlers fight/Getty Images

The Japanese, on the basis of prehistoric images, believe that something like sumo has always existed in Japan, and the first written record of sumo is more than 1,300 years old. Early sumo wrestlers often fought to the death, as in a duel, but over time, the rules have become more humane, although sumo wrestlers still sometimes die. Sumo wrestlers look oddly aesthetic by non-Japanese standards. And it’s not just the near-total nudity. They wear sleek chonmage braids and style their hair in unique ways. In fact, braids and special hairstyles are also attributes of the samurai, the military caste of ancient Japan, so that death does not scare them. The Japanese name for a sumo wrestler (rikishi) is composed of two characters: strength and samurai.

Professional sumo tournaments began in 1684, and since 1757, for almost 270 years, the results of all the tournaments have been recorded in writing. In all that time, no one has ever managed to win as many tournaments as the Great Taihō. His record of thirty-two tournaments seemed unlikely to be broken. And then Hakuhō won a tournament for the thirty-third time. Interestingly, the number thirty-three is considered unlucky in Japan, especially for women, as it is phonetically similar to the word ‘calamity’.

Taihō: The Greatest and Most Beautiful

In August 1945, after two weeks of fighting between Soviet and Japanese troops, South Sakhalin, or Karafuto Prefecture in Japanese, which had been part of the Japanese Empire after the victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, was finally conquered and annexed by the Soviet Union. At the same time, a mass exodus of the local Japanese population began, primarily to the northern island of Hokkaido. Among the nearly 100,000 evacuees was the son of a Japanese woman from Sakhalin and a Ukrainian born near Kharkiv—five-year-old Ivan Boryshko. His father, a White Guard and participant in military actions against the Bolsheviks, was arrested by the Soviet troops, and nothing more is known about him since, although Ivan never stopped looking for his father even as an adult. Back then, in 1945, he certainly did not know that fifteen years later he would win his first tournament in the highest division of sumo, and all of Japan would recognize him as Taihō—the Great Phoenix.i

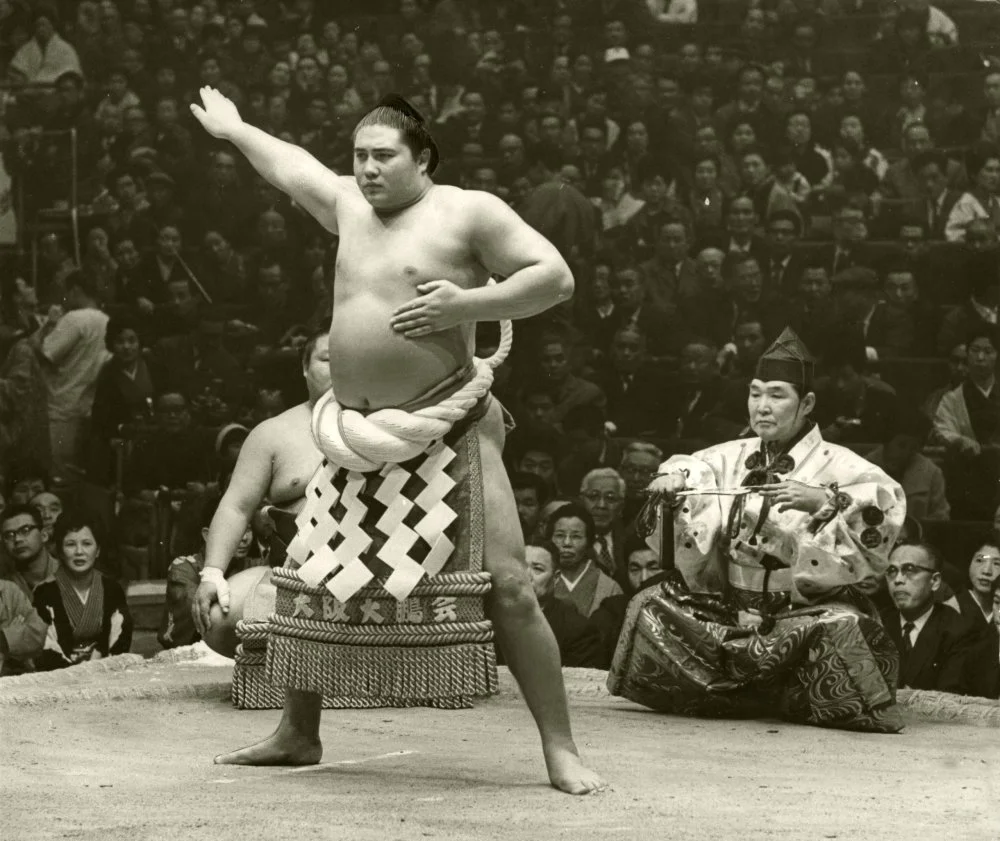

Yokozuna, the Taiho sumo champion at the spring tournament in Osaka, Japan. 1964/The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images

The Great Phoenix turned out not only to follow the graceful, breathtaking style of sumo, which was beneficial for the dejected Japanese of the postwar era, but also a rather open-minded person. He traveled, including to the Soviet Union, where he tried to find his father, communicated with the press, and arranged a tour for journalists at his lavish wedding, which was previously unthinkable for the closed, private life of conservative sumo wrestlers. Later, this became the norm. And outside the ring (dohyō), he was known as a kind and amiable man, and contrary to the militant samurai morals of rikishi, he had close and friendly relations with his fierce rival, Yokozuna Kashiwado. He also befriended Hakuhō and always gave him advice when it was sought from him.

A Cherished Friendship

In March 2000, a sixteen-year-old Mongolian boy, Erkhem-Ochiryn Sanchirbold, who lifted weights as a child and had a strong physique, was brought to the Miyagino sumo stable (called heya or beya in Japanese). Sumo scouts saw a great future in the boy, but he was not very eager to become a sumo wrestler himself. According to him, he had only agreed to move to Japan because he wanted to fly in a real airplane. Not knowing the language, not understanding why everyone was scolding and beating him, or what they wanted from him in general, he became depressed and was seriously considering running away to his homeland. Unsurprisingly, the first Mongolian in sumo, the future komusubii

Hakuho Sho picks up a trophy after winning a sumo tournament. 2014/The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images

So, they decided to find a Mongolian companion for the depressed Sanchirbold so that he wouldn’t miss his homeland and would at least have someone to socialize with until he learned Japanese. They chose a puny fifteen-year-old boy who had been rejected by other stables because he was underweight. The boys quickly became friends, doing everything together, even sleeping in the same bed at first, to the ridicule of their older stablemates. His name was Mönkhbatyn Davaajargal, but when it came time to choose a professional pseudonym and, unhindered by modesty and inspired by the shikonai

Sanchirbold, who competed under the shikona Ryūō, unfortunately did not have a successful sumo career. He reached the top division, but a broken neck and other injuries prevented him from advancing further. However, he had a successful career as a restaurateur and manager, whose client was his best friend and the most decorated sumo wrestler in history. He was also invited by Hakuhō to serve as a tachimochi, a sword carrier for the yokozuna, during the ceremonial entrance of the yokozuna onto the platform (dohyō-iri). This is considered a great honor for lower-ranked sumo wrestlers.

Not long ago, on 4 February 2024, in Kokugikan, the high temple of sumo, an official retirement ceremony was held for the most successful Georgian in sumo, the former ōzeki Tochinoshin, where they cut off his chonmage and deprived him of his shikona. The enfant terrible of modern sumo, ex-yokozuna Asashōryū, came from Mongolia to cut off part of his hair. He said that after his career ended, he became close friends with the Georgian and added something that everyone understood but not everyone liked: ‘As foreigners fighting in the same ring, we all experienced something special.’

During a trip to Kazakhstan, the same Yokozuna Asashōryū advised the young Almaty judoka Yersin Baltagul, whose father he knew, to take up sumo and personally supported his studies in high school and later at university. In March 2023, the twenty-five-year-old Kazakh Kinbozan made his debut at the spring tournament in Osaka. Who knows what kind of career one can expect from this foreign sumo wrestler, yet another in a line of many.

Children's sumo section/The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images

The Importance of Your Birthplace

Cricket is often said to be an Indian game that was somehow invented in England. In sumo, with its 2,000-year history, ultra-conservative rules, and old-fashioned morals, no one would ever think twice about appropriating something. All the rituals in sumo—from burying sacrificial plants for a good harvest in the dohyō, to dressing the referees (gyōji in Japanese)—are rooted in the religious rituals of Shintoism. Because the ring is the embodiment of a Shinto temple, the religion forbids a woman to enter it, whether she is a newborn daughter in the arms of a sumo wrestler or a cardiologist trying to revive the mayor after a heart attack (incidentally she was not allowed to). It wasn’t until 2021, and only after the death of twenty-eight-year-old sumo wrestler Hibikiryu, that it was finally deemed appropriate to have a medical team at the tournament. Traditionally, complaining of pain or injury was considered unworthy of a sumo wrestler, and people with obvious concussions, head injuries, or dislocated joints would sometimes try to come out for a replay in the event of a draw. Only recently, after consultation with doctors, can an injured wrestler be kept out of the next match. So it's not surprising that in the age of smartphones, K-pop, and artificial intelligence, sumo often seems like a time capsule from the Japan of the past, the most Japanese of all Japanese traditions.

However, of the six yokozuna honoured with this title in the twenty-first century, only one—Kisenosato—was born on Japanese soil. Four of the six were born in the Mongolian capital of Ulaanbaatar (Asashōryū, Hakuhō, Harumafuji, and Terunofuji), while the fifth (Kakuryū) was born in the western Mongolian province of Sükhbaatar. This is despite the fact that since 2002 the Japan Sumo Association has imposed restrictions on foreigners—there can only be a maximum of one per stable, or roughly one foreigner for every fifteen to twenty locals. Despite this, Mongolians won fifty-six of fifty-eight tournaments between 2006 and 2016.

Attempts were made to explain this by the average height advantage of Mongolian sumo wrestlers, their national meat diet, and the techniques of Mongolian wrestling (Ündesnii bökh in Mongolian). On this occasion, the former komusubi Mainoumi even wrote a book—Why Can't the Japanese Become Yokozuna?—in which he categorically attributed the success of the Mongolian sumo wrestlers to the metaphysical sense of the ‘hungry spirit’, which the soft Japanese youth in the era of prosperity had completely lost.

Sumo wrestlers after the match/Alamy

The overwhelming success of Mongolian sumo wrestlers in the ring was accompanied by their dominance in the lists of most notorious sensations and scandals, and the rhetoric concerning them often dwelled on their non-Japanese origin. Presidents of sumo associations and even government officials have repeatedly complained about the reluctance of some foreigners to assimilate, recognize, and adopt Japanese ‘dignity’. In January 2010, Yokozuna Asashōryū (born Dolgorsürengiin Dagvadorj) was accused of drunkenly beating up a restaurant worker, and when the incident became public, he was forced to resign and then leave the country. Asashōryū was always known for his brash and defiant behavior both in and out of the ring, even refusing to take Japanese citizenship, but the elegance of sumo could not be taken away from him. With each passing year, he got closer and closer to Taihō’s ‘immortal’ record, winning twenty-five tournaments by the age of twenty-nine. The scandal and his subsequent retirement from the sport at the height of his fame gave rise to many conspiracy theories. The main one, voiced even by Mongolian politicians, is that the severity of the punishment was due to the desire of sumo officials to preserve Taihō’s record.

However, the issue of discrimination against non-Japanese yokozuna was not only associated with defiant Mongolian champions such as Asashōryū and Harumafuji, who both publicly refused to apply for Japanese citizenship and thus tie their futures to Japan. It was also tied with the comparatively respectable Hakuhō and the eternally good-natured Kakuryū. As a result, the Japanese Sumo Association hastily made Japanese citizenship a prerequisite for coaching, and Hakuhō himself, the absolute record holder in the number of championships won, was denied the automatic status of a sumo elder (toshiyori) for outstanding yokozuna, which is a prerequisite for an oyakata (the head and coach of the stable). The Japanese yokozuna Takanohana, however, was awarded this status for only twenty-two championships.

Sumo wrestler Kotonowaka (left) attends a press conference at Sadogatake stable in Matsudo. 2024/The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images

Embedded in Your Roots

Despite its apparent complexity, the essence of sumo is quite simple—stay on your feet inside the ring at all costs. Touching the ground with any part of the body other than the feet, even the fingertips, or stepping outside the ring is a loss. The association with the ground is not accidental as the ring is made entirely of clay and sand.

In the superstitious world of sumo, in which the color of mawashi, the sumo wrestler’s silk loincloth, can be held at fault for a sumo wrestler's unsuccessful performance, the belief in continuity, including hereditary continuity, plays a very important role. Great Hakuhō is the son of the great Mongolian wrestler Jigjidiin Mönkhbat, six-time champion in Mongolian wrestling and the first Olympic medalist in Mongolian history (silver, 1968). The rebellious Asashōryū also comes from a family of famous wrestlers. His own nephew is the ōzeki Hoshoryu. The newly promoted ōzeki, and coincidentally Japan’s most stable sumo wrestler currently, Kotonowaka is the son of ex-sekiwakei

A young baseball team. Japan/Getty Images

The Morning Sun Never Lasts a Day

On 28 January 2023, the sumo world bid farewell to Hakuhō. The danpatsu-shiki, or official retirement ceremony, took place at Tokyo’s Kokugikan, the main sumo palace. At the end of a wrestler's career, the chonmage is cut off, as these samurai braids are only permitted to be worn by active sumo wrestlers and some kabuki theater performers. With the braids, the wrestler also loses his shikona, so now he is Miyagino Oyakata. But his record of forty-five championships, thirteen more than the Great Taihō, now certainly seems to have brought him immortality.

Meanwhile, the Japanese, as well as the rest of the world, are beginning to lose interest in this archaic and perhaps most closed sport. Its religious philosophy seems less and less compatible with the worldview of young Japanese people, and the attempts to keep sumo a purely Japanese sport are diminishing international interest in it. The absolutely spartan and exclusively male world of sumo, with its rigid hierarchy and brutal discipline, violence, humiliation, constant injuries, and the prospect of living ten to fifteen years less than the average Japanese citizen, no longer attracts young people. As the culture changes, so does the social appeal of sumo wrestlers as role models, commercial projects, and marriage options. This is especially noticeable when the internet is flooded with the news that twenty-nine-year-old Japanese baseball player Shohei Ohtani has signed the biggest contract in sports history—worth $700 million—with the Los Angeles Dodgers.