Nicolas Poussin, Ruth and Boaz Poussin/Wikimedia Commons

Since time immemorial, cooked chickpeas ground with ingredients like tahini sesame paste and olive oil—and perhaps some lemon juice—has been a very popular snack for peasants, and indeed people from all walks of life, in the Middle East. In recent times, however, it has undergone a huge transformation, transcending its regional roots to become a global phenomenon. In this article, we explore the fascinating journey of hummus, from its humble origins to a cult food for the European and American middle classes.

Old Testament Chametz

We know that hummus originated in one of the countries in the Middle East, but it is not certain which one. The earliest written recipes in the region date to 1700 BCE, which were inscribed on clay tablets in the Akkadian language and included recipes for simple and complex dishes. However, nothing in them resembles hummus.

Pre-cuneiform writing clay tablet noting food rations. Archives of the Temple of the Sky God. Around 3300 BC. The Louvre Museum/shutterstock

The next significant source to explore for any mention of hummus is the Bible. In 2007, an Israeli writer named Meir Shalev published an article titled ‘Hummus Is Ours’, in which he tried to prove the existence of hummus in the times of the Old Testament by quoting from the Book of Ruth (2:14):

At mealtime, Boaz said to her, ‘Come here. Have some bread and dip it in the wine vinegar.’ When she sat down with the harvesters, he offered her some roasted grain. She ate all she wanted and had some left over.

In the original text, the bread is dipped into ‘homes’. In modern Hebrew, this word means vinegar, but Shalev thinks that they were referring to ancient hummus. Today, depending on the context, Hebrew speakers use the word ‘hummus’ to refer to chickpeas or hummus itself. However, it is worth noting that this is a relatively new word borrowed from Arabic. Himsa, an alternative word, was used in Hebrew and referred to chickpeas.

Shalev thinks that the words ‘hummus’, ‘himsa’, and ‘homes’ all have their origins in semitic languages, which are derived from a triliteral root made up of the letters h-m-s. In these languages, many words are created from a set of three consonants. He suggests that because these words share the same root letters, they are linguistically and perhaps culturally connected. This means that Boaz and Ruth could have been dipping their bread into chickpea paste, especially since it sours quickly and starts resembling vinegar in taste. This version is not without controversy but quite plausible.

Hummus, the Heart’s Delight

Leaving Ruth and Boaz aside, since we are unlikely to ever find out exactly what they ate their bread with in the autumn of 1385 BCE (traditionally, the events in the Book of Ruth are said to have occurred in this year), let us fast forward the calendar 2,500 years to finally find the first recipe that undoubtedly refers to hummus.

The tradition of creating cookbooks in the territory of what was Mesopotamia has endured since Babylonian times. The nobles of the Persian courts of the Sasanian era (third to seventh century BCE) had private collections of recipes. By the tenth century, the habit of maintaining cookbooks had firmly established itself in the courts of Baghdad. Khalifs commissioned poems and songs about food and rewarded those who invented new dishes. The scribes had to write at least a few facts about every single dish so that the instructions could be read out to the cooks who were unable to read.

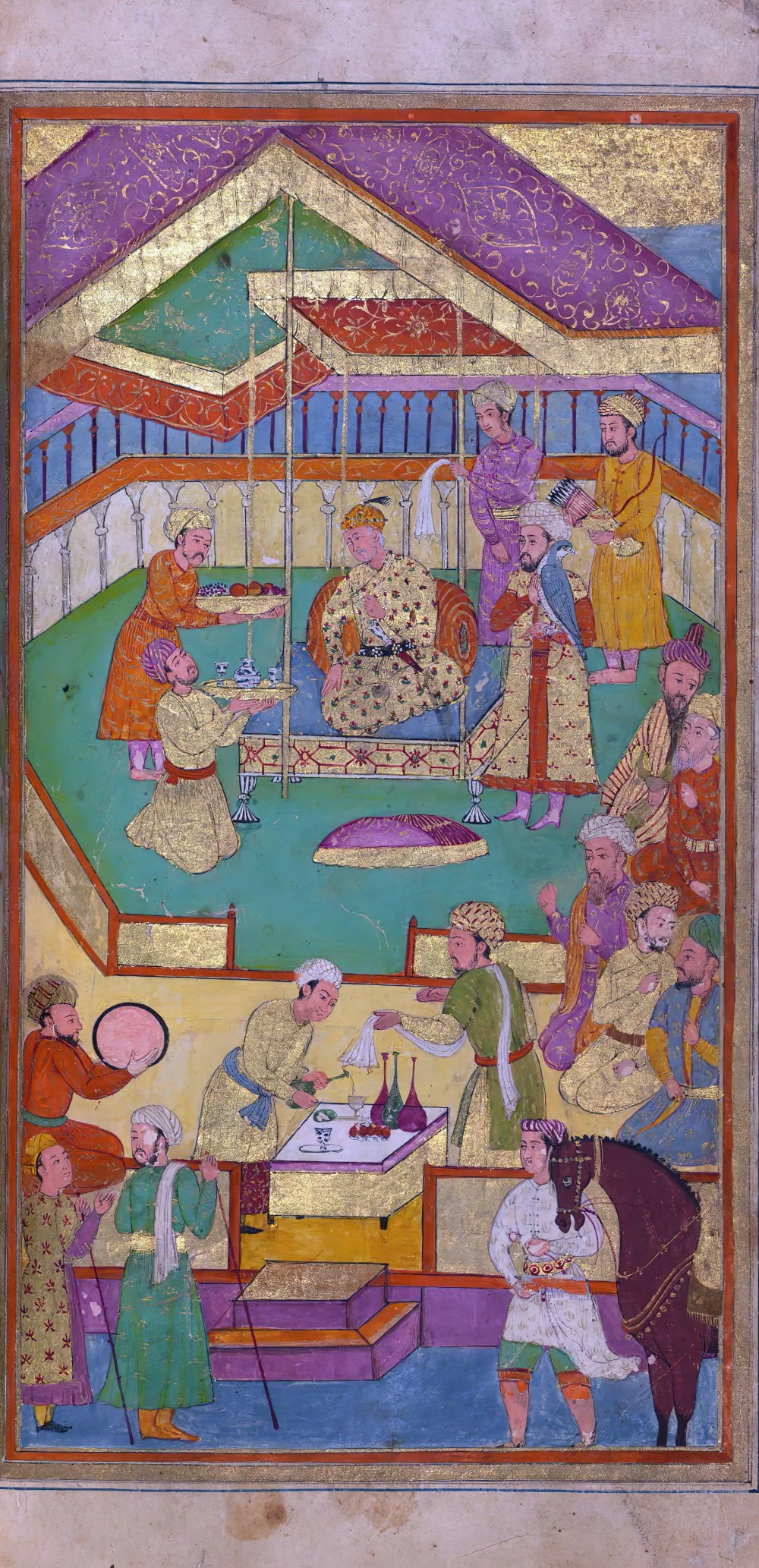

Muhammad Ali, A feast in a pavilion setting, 17th century/Wikimedia Commons

Hummus recipes first appear in Arabic books dating back to the thirteenth century BCE. Among them is a cookbook by an unknown author, recently published in English with the title of Scents and Flavors: A Syrian Cookbook. Another significant volume that contains the recipe is Book of the Relation with the Beloved in the Description of the Best Dishes and Spices by the Aleppo historian Ibn Al-Adim (died 1262).

The recipe from Scents and Flavors reads:

Take chickpeas and boil them. When they are cooked, mash them with vinegar, olive oil, tahini, black pepper, atraf al-tib,i

Hummus/Getty images

The recipe also contains advice at the end about the consistency of the hummus, saying,

‘It needs to retain its shape when scooped up with a piece of bread’.

The Chickpeas Are Jumping Out of the Pot

Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī (1207–1273), a Persian Sufi1

Jalal al-Din Rumi, Maulana - A Court Scene with Food and Music/Alamy

A chickpea leaps almost over the rim of the pot

Where it’s being boiled.

‘Why are you doing this to me?’

The cook knocks him down with the ladle.

‘Don’t you try to jump out.

You think I’m torturing you.

But I’m giving you flavour,

So you can mix with spices and rice

And be the lovely vitality of a human being.

Remember when you drank rain in the garden?

That was for this.’

Eventually the chickpea

Will say to the cook,

‘Boil me some more.

Hit me with the skimming spoon.

I can’t do this by myself.

I’m like an elephant that dreams of gardens

back in Hindustan and doesn’t pay attention

to his rider. You’re my cook, my driver,

my way to existence. I love your cooking.’

The cook says,

‘I was once like you,

Fresh from the ground. Then I boiled in time,

And boiled in the body, two fierce boilings.

My animal soul grew powerful.

I controlled it with some practices,

And boiled some more, and boiled

Once beyond that,

And became your teacher.’

Strangely, after its magnificent debut in the Middle Ages, hummus disappeared from cookbooks for quite some time. It appears again in 1885 in a book called The Master Chef’s Culinary Memento for Housewives by Lebanese author Khalil Sarkees. His recipe is close to the contemporary one and contains chickpeas, garlic, lemon juice, and tahini. By that time, it is worth noting, hummus was a very popular dish in the Middle East and in some countries of Central Asia, but it was practically unknown beyond those regions.

Bowl of raw chickpeas/Getty images

Victory March

Until the 1970s, the thick chickpea dip was treated as a suspicious exotic dish in Europe and the US. It was meant to be eaten only by the hippies, ‘the flower children’ who were into everything eastern, or by the eastern people, such as the Turks and Lebanese, themselves. Hummus first appeared in the UK during the late 1980s at Waitrose, a chain of stores known for catering to the upper and middle classes, where exotic goods were the norm.

However, an ordinary working man from Manchester could not even dream of hummus in those days. Even up until the noughties, a person asking for hummus in a village supermarket would simply not be understood. An excerpt from ‘A History of Hummus’, a short piece of fiction written for a performance by Matt Barton, gives us a glimpse of what such a conversation may sound like.

On the way back to Sparrow Hall, Harry stopped off at the Pioneer, to buy some hummus.

The Pioneer in Broadway HAD NO HUMMUS.

He asked one of the assistants, ‘Where do you keep the hummus?’ But the assistant didn’t know what he was talking about.

‘I hate it round here,’ Harry told his mum and dad when he got home, ‘they don’t even have hummus in the Pioneer.’

‘What’s hummus?’ said Harry’s dad. Christ! Harry couldn’t believe these were his actual parents.

To this day, hummus still has the reputation of a pretentious and exotic ‘food of the rich’ in some parts of Europe. Even though the world has become ‘global’, with everyone traveling everywhere, the rise of vegetarianism and healthy lifestyles amongst the middle class has made hummus a very handy thing to have in the fridge. Now, the British Department of Health and Social Care recommends it to pregnant women, and hummus sales in the US are close to USD 1 billion per year.

Hummus is rich in vegetable protein, non-saturated fats, vegetable fibre, vitamin B6 and iron. On average, a hundred grams of hummus contains 166 calories, but there are between five and twenty-five variations of hummus made by different manufacturers, including a low-fat one, where the calories are reduced by one third.

Political аnd Social Mural Paintings And Graffitis On The Israeli West Bank Barrier In Bethlehem, West Bank On March 13, 2018/ Artur Widak/NurPhoto/Legion-Media

Today, hummus can be found in any self-respecting supermarket. It is made with many different ingredients, including pine nuts, chili peppers, garlic, parsley, ground cumin, lemon, pumpkin puree, cocoa, smoked paprika, sun-dried tomatoes, feta cheese, and fried onions. As the Times columnist Alex Renton said: ‘We imported it, adapted it and now the people who invented it wouldn't recognize it.’

What to read

Мокич Андрей. Хумус и соленые лимоны. Яркая кухня Ближнего Востока. — Хлебсоль, 2022.

Scents and Flavors. A Syrian Cookbook, by Charles Perry (Translator). 2020.

Barton, Matt. ‘A History of Hummus’. 2023.