Among the Mongols, tea is the most common and popular form of both beverage and food.

In Mongolia, tea is called tsai, and the most common form of tea drunk by the Mongolians is süütei tsai. Süü means ‘milk’ and süütei tsai means ‘tea with milk’. In Mongolian tradition, tea holds a special place as the primary and most esteemed dish on the table. It is regarded with great respect and is known as ideenii deej, which translates to ‘the pinnacle of foods’. Thus, tea is not simply something to consume but also an integral part of culture and tradition in the country.

Tea is accompanied by rituals and etiquette that are strictly observed. The first ritual is offering freshly brewed milk tea to the Eternal Blue Sky and the spirits of nature in the morning. The lady of the yurt exits the yurt with a dipper of tea every morning and splashes it upward, thus offering the new tea to the sky, the spirits of the area, and the spirits of revered mountains, usually from the family's ancestral lands. This custom is faithfully followed even by people who live in urban areas. In a city, one can see women carrying tea-filled water dippers in the morning. Of course, instead of at a yurt's door, they stand on the balconies of their apartments and fulfill the ritual. Those passing below their windows, should they get splashed with tea, will not be angry but will consider it a good omen instead. Many families also place a cup of milk tea on the Buddhist altar in their homes in the morning.

Tsaatan woman offering tea as welcome gift in her ger/ Pascal Mannaerts/Alamy

Traditionally, the first bowl of tea is served to the head of the household and then to the others in order of seniority. The tea is offered with both hands or only with the right hand, which is supported at the elbow by the left hand. The tea is also received with both hands or with the right hand only. In Mongolia, the general rule is to use the right hand, and all items should be given or received with either this hand or with both hands; it's inappropriate to do so with rolled-up sleeves. Additionally, tea is typically served at the start of the meal while waiting for the main course. Once the tea is on the table, they also place boortsog,i

Every Mongolian family brews süütei tsai several times a day. As the well-known joke goes, a foreigner once asked, ‘When and how do Mongolians drink tea?’ and another, more observant, person answered him, ‘Mongolians drink tea before meals, during meals, after meals, and instead of meals.’ Mongolians are indeed very fond of tea, drinking it on various occasions and even without occasion, which, of course, is reflected in the language. Lunch time is known as tsainy tsag, which translates as ‘tea time’, and the dining area is called tsainy gazar, which means ‘the place of tea’.

There are several types of milk tea made in Mongolia, among which süütei tsai and hiitstei tsai are the most common. Süütei tsai is drunk every day, while hiitste tsai, which means ‘tea with additives’ or ‘specially prepared tea’, is usually made on the weekends, when there is enough time to brew it.

Mongols drink tea in their yurt/Edwin Tan/Getty Images

To prepare hiitste tsai, you heat up a kazan (cauldron), then add pieces of lamb fat or shar tos (‘yellow oil’) and fry some flour in it. Then you add pearl barley or, less commonly, rice, water, and tea leaves. Boil the mixture for a while and then add some milk with a portion of salt, and boil it again. The boiling tea is mixed well with a ladle from the bottom upward, pouring the tea back into the cauldron from a height, repeating this procedure until the tea starts boiling. As a result, the tea turns out thick, tasty, and hearty. Then, depending on the occasion, the finished tea is then poured out into silver, porcelain, or wooden bowls. It is important to remember that Mongolians do not always drink such thick tea, and this is usually made for special occasions.

On a regular day, a lighter version of this tea is usually made: süütei tsai without lamb fat and pearl barley. The recipe calls for only water, tea, milk and salt, and the shar tos is added to the prepared tea when it is poured into a thermos. People in cities drink such tea on weekdays, while rural residents enjoy it during the warm season.

It is noteworthy that all the recipes for Mongolian milk tea have one key ingredient: shar tos, which means ‘yellow oil’, sometimes mistakenly thought to be real cow’s butter or ghee (melted and hardened cow’s milk butter). In fact, shar tos is a unique product. In central and eastern Mongolia, this yellow butter oil is made from öröm, while in the western part of the country, it is made from airag.

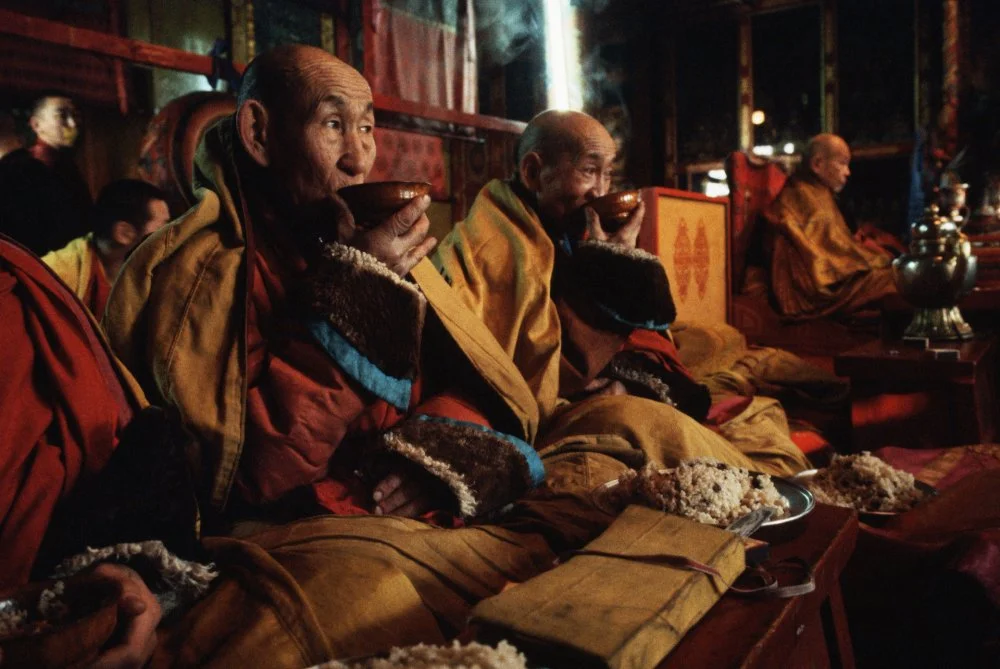

Llamas at Gandan Monastery having breakfast of rice and tea before prayers. Mongolia/ Dean Conger/Getty Images

Airag is typically made from fermenting cow or yak milk, although Mongolians also refer to kumis, made from mare's milk, as airag. It is made by vigorously whipping warm, fresh milk for several hours until oil starts to appear on the surface. This oil, sometimes referred to as airag butter, is then carefully collected in a special container or even a sheep's intestine. This is how shar tos is made in western Mongolia. In central and eastern Mongolia, it is mainly obtained from another product called öröm (milk skins). First, cow's milk is repeatedly skimmed using a ladle. This skimming action creates foamy layers, or 'skins', on the surface of the milk. These milk skins are then collected and melted in a hot pan. After they harden, the oil is fermented in wooden vessels or vessels made from cow’s intestines, which is how shar tos is stored.

In Mongolia, shar tos is made throughout the summer, and it can be made from the milk of cows, camels, sheep, and goats, as a result of which the oil will vary in color and taste. It is a key ingredient to make süütei tsai, giving it a wonderful taste and aroma, reminding us of summer during cold winter days, of fresh airag and white (dairy) food.

Nomads in Asia, unlike Europe and other parts of the world, have been drinking tea throughout their history as they have been neighbors with China for millennia. Chinese traders always exchanged fabrics, silks, and, of course, tea with the Mongols. After the signing of the Bura Treaty between Manchuria and tsarist Russia in 1728, the Great Tea Road began to pass through Mongolian territory, which ran to Kyakhta, then through Siberia to Moscow and from there to Western Europe. This route brought significant income to the Mongols. Along with silver, bricks of tea soon became a unit of currency, an interesting substitute for money. Until the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the Great Tea Road was a very profitable route for the Mongols.

Song dynasty painting showing commoners engaged in tea competition/Wikimedia commons

After the fall of the Manchurian Empire in 1911, Mongolia declared independence. However, after 1921, Mongolia fell under the influence of Soviet Russia, although it tried to continue independent development until the 1930s. In 1929, Mongolia’s trade landscape shifted dramatically. Under pressure from the Soviets and the Communist International (Comintern), all foreign businesses, including Chinese companies, were expelled from Mongolia, and trade with other countries, except Soviet Russia, was discontinued. Thus, the tea trade with China also ceased. As a result, tea imports from China, particularly the popular yellow tea, shar tsai, came to a halt. Mongolians, who had grown fond of this Chinese tea, were now forced to find a new source for their favorite beverage.

As the sole trading partner of Mongolia, the Soviet Union began to supply Mongolians with pressed ‘green’ tea from Georgia, but it was a low-grade tea with a lot of twigs. It was difficult for Mongols, long accustomed to Chinese quality, to switch to Georgian tea, and many elderly people complained about the quality of Russian tea. In a marketing move to sell this tea to the Mongolians and get them accustomed to it, gold earrings and rings were pressed into the tea. The strategy relied on generating excitement about being ‘lucky’, hoping that the chance of finding something valuable would overcome the Mongolians’ hesitation. As the saying goes, in the absence of fish, a crayfish will do. And so, during the years of socialism, Mongols got used to brewing Georgian tile tea and even grew to love it. And after 1990, when the imports from Georgia stopped, many complained that it was difficult for them to drink Chinese ‘black’ tea. The change was particularly hard for the elderly as they complained either of high blood pressure, weakness, or poor health and demanded the return of their beloved ‘green tea’.

In addition to tea from China, Mongolians also gather and consume herbal teas. Made from over a hundred types of different plants, these teas are made into specific blends. Today, there is great demand for tea produced in the Khövsgöl aimag (province) in western Mongolia, particularly for a blend known as ‘Ikh taiga’, or the ‘Great Taiga’.

Tea brick with hammer and sickle and cyrillic script at the market Ulaangom Mongolei/Alamy

There are many natural zones across the vast territory of Mongolia, and each region has its own methods of brewing tea using local ingredients. These are further influenced by family traditions, creating a huge diversity of tea traditions in the country. Apart from the traditional süütei tsai and hiitste tsai, people also drink teas with butter, tea prepared in a cup, teas with medicinal herbs, and more.

In the western and central regions of the country, people drink salted tea, while in the eastern and Gobi aimags , where it is hotter than in other regions, tea is consumed without salt. This is probably due to the saltier and harder well water of the Gobi. The ingredients used to brew tea—besides milk, water, and tea leaves—may include dried medicinal plants, various types of salts, and dairy products, such as shar tos or clotted cream, as well as pieces of mutton fat, cooked and sliced meat, grains, dumplings, and noodles. In some places in Mongolia, in addition to ordinary salt, people use khujir, white alkaline minerals growing in the steppes. Khujir contains many different salts and trace elements, such as copper, zinc, iron, and iodine.

Special attention should be paid to the tea with dumplings, or banshtai tsai. A popular comfort food is the ‘tea with seven dumplings’, believed to have healing properties. Hence, it's drunk when one is feeling tired or slightly unwell. This tea features small dumplings stuffed with lamb, onions and salt. First, clotted cream is melted in a hot kazan, and then flour is added and toasted slightly. Brewed tea is poured in next, and lamb meat on the bone is added. Everything gets boiled together for a while, after which dumplings are added and cooked. Finally, milk is added and the whole mixture is boiled once more. The tea is poured into pialas, and seven dumplings are added to each cup.

Tea transportation in Kyakhta (Russian Empire). Engraving of the 19th century. Kyakhta is a town and the administrative center of Kyakhtinsky District in the Republic of Buryatia, Russia. Engraving of the 19th century/Alamy

Nowadays, Mongolia started producing instant teas, which have become popular in offices and among Mongolians studying and working abroad. The most famous are the instant süütei tsai ‘Khaan’ and hiitstei tsai ‘Khaantan’, with both names meaning ‘khan’.

As is clear, Mongolian teas, due to their unique ingredients and special preparation methods, are not simply beverages but more like soups or even meals. In the harsh weather conditions of Mongolia, such thick teas are very necessary: they are calorie-rich, are hearty, and provide warmth. It's especially pleasant to drink hiitstei tsai during sand storms in the spring, when it gets cold and dry winds and dusty storms are blowing, making being outside very tiring. There's nothing better at this time than sitting at home in the warmth, drinking hiitstei tsai or tea with dumplings, and listening to the sounds of the wind gusting and sand hitting your windows.

Mongolian people visit their family and friends in their yurts during Tsagaan Tsar, the mongolian new year/Alamy