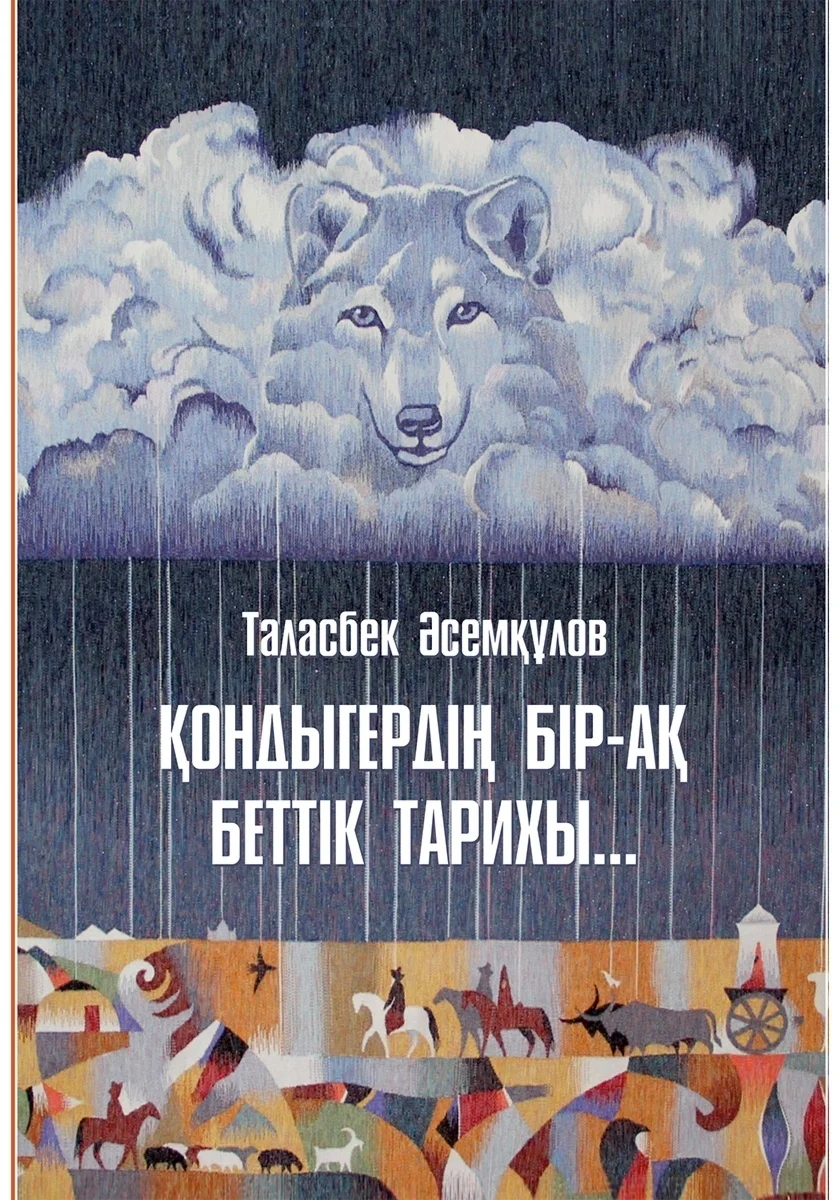

In 2024, the work of the celebrated scholar Talasbek Asemkulov, also a much-loved writer and küishi, was collected in a new book titled A One-Page Story of Qondyger. This collection dives into the myths, historical events, and traditions of the Kazakh people, and even covers social issues, highlighting Asemkulov’s research into Kazakh history and culture. Gathered from a long and illustrious career, his writings offer a unique window into the heart and soul of Kazakhstan.

In the world of Kazakh literature, Talasbek Asemkulov is a groundbreaking figure. He is one of the few writers who has captured the essence of the traditional Kazakh musical art of küi and rendered it into words. His writing is very popular among the youth and has sparked a renewed interest in Kazakh spirituality since the country's independence. Rejecting the traditional ideas of socialist realism, he has reinterpreted the art of küi, mythology, and epic poems, which are the cornerstones of Turkic worldview, from an intellectual and philosophical perspective. It is also important to note that Asemkulov’s influence extends well beyond literature. In his work, he has deciphered the core aspects of Kazakh thought, significantly shaping the development of the decolonial discourse in Kazakhstan.

Talasbek Asemkulov/From open sources

Some of the articles included in A One-Page Story of Qondyger were written a long time ago but remained unpublished because the direction of Asemkulov’s philosophical inquiries contradicted Soviet ideology. The research articles and critical works he wrote in a later period were published in periodicals and online portals, not only resonating deeply with readers but also becoming sought-after texts among young writers. His work even reached the Kazakh-speaking readership in China, where they were widely distributed as brochures with copies in Arabic. Even a brief acquaintance with Asemkulov's publications clearly demonstrates that each one breathes with a boundless love for Kazakh spirituality and cultural life. One of his most unique articles is devoted to the narratives and mythological meanings of Kazakh epics, as well as the similarities in content between the Turkic epic Alpamys and Homer's Odyssey.

‘Love … What is this feeling? Where does it arise, and where is it directed to?’

‘Love … What is this feeling? Where does it arise, and where is it directed to?’ This question, perhaps the most profound question Asemkulov raises, delves into the very essence of the Turkic baqsy (shaman) and the Turkic worldview. He explains that with the advent of Islam, the poetics of the Turkic world were transformed by the orthodox morality of Islam, and the Turkic gods alive in myths were desacralized. The once-divine Turkic heroes were stripped of their mythical status and classified as ordinary, religious figures. Additionally, Asemkulov also asserts that epic poems such as Qozy Körpesh–Bayan Sulu, Alpamys, and Qobylandy retained a part of their mythological character, but their content evolved over time. He meticulously examines these epics, providing surprising new parallels to the narratives of Homer's epic works.

Postage stamp of the USSR in 1988, dedicated to the Uzbek folk epic "Alpamysh-Batyr"/Wikimedia Commons

For instance, Asemkulov argues that the divine characters in the epic poem Alpamys Batyr bear an uncanny resemblance to those in the Odyssey. Alpamys, underestimating the cunning of the evil old woman Jalmauyz Kempir, gets thrown into a deep well by her; however, he is saved by the goddess of forgetfulness, Karakoz, the daughter of King Taishin. But after living with her, he loses his memory, and only regains it when he sees in a dream that the son of the dark night, Ultan, is going to marry his beloved Gulbarshin, who is waiting for him at home. Alpamys hastily returns and defeats Ultan. Similar narratives are found in epics about heroism and love, such as the epic Qobylandy.

‘The world of Kazakh culture inherited from our ancestors is an inexhaustible wealth, as boundless as the elevation of the human spirit and its growth.’

In his work, Asemkulov discusses the significance of Kazakh epics, legends, and tales and perceives them as testament to the evolution and endurance of the human spirit, representing the pinnacle of Kazakh cultural achievement. The author writes: ‘The world of Kazakh culture inherited from our ancestors is an inexhaustible wealth, as boundless as the elevation of the human spirit and its growth.’ According to him, Kazakh epics encompass the Platonic idea of eidos, which plays an important role in understanding the universe, the structure of the world, and world order. For example, using Qozy Körpesh–Bayan Sulu, Qobylandy, and Alpamys Batyr as examples, Asemkulov shows how human feelings born from dualistic ideas intricately intertwine in legends and epics, sometimes contradictory and occasionally harmonious. He writes that ‘the dualistic idea in the lyrical epic Qozy Körpesh–Bayan Sulu grows into a love drama, and then, as a result of the centuries-old conflicts with Iran and the Dzungar khanate, becomes the theme of the struggle against the tyrant in the epics Alpamys and Qobylandy’.

Mausoleum of Kozy-Korpesh Bayan Sulu/Wikimedia Commons

In the Kazakh cultural context, there are various interpretations of the image of a horse. According to Talasbek Asemkulov, the countless horses in Qozy Körpesh–Bayan Sulu represent the image of the world and space, which transitions into a person and becomes their soul. If the character Mamabike symbolizes the sorrow and grief of the human soul, then Qodar and Qarabai reveal another darker side of the human soul, its inherent cruelty and cunning. If Mamabike enters a person's heart, they will plunge into perpetual sadness, but if Bayan and Qozy Körpesh retain control, love and goodness, peace and harmony will reign on earth.

These dualistic confrontations show us that the meaning of human life is born from the struggle between noble qualities and base instincts within the soul. Talasbek Asemkulov says that qualities such as humanity, honor, and kindness have always been recognized as the highest virtues in Kazakh culture, and this is reflected in the expression ‘the defenselessness of others is on your conscience’. Accordingly, the annals of world history demonstrate that the victorious were usually fierce peoples who despised the weaknesses of others.

For example, the image of the treacherous and evil old woman from Alpamys, her terrible villainies, which she, as a demonic embodiment of evil, commits against Alpamys, considered a symbol of victory and inspiration, leads to the battle of two dualistic ideas. Here, the human spirit awakens from years of lethargy, makes a leap, and enters the fight for a better life, culminating in the triumph of justice. In any case, the figurative and symbolic meanings of the epics that Asemkulov examined harmonize with the universal values reflected in world literature and resonate with the best human qualities in the understanding of Kazakh culture.

Zhalmauyz kempir/Dall-e

Overall, A One-Page Story of Qondyger is a remarkable work that has found its rightful place in the world of Kazakh spirituality. It should be noted that this work originated from one of the extensive data sets Asemkulov had recorded, when he faced various difficulties in gaining access to a secret archive in Iran to study an article critical to his research. His friend Lev Gumilyov came to his aid, empathetically giving up his place in line for access to the archive.

‘I was frightened by the scale of the pseudoscience called Soviet history, by this endless fake narrative, superficially resembling real history, with references to well-known scholars.

Talasbek Asemkulov, with his characteristic bravery and aplomb, continued to work despite the ideological censorship of the Soviet era, noting: ‘I was frightened by the scale of the pseudoscience called Soviet history, by this endless fake narrative, superficially resembling real history, with references to well-known scholars. Try to question not the entire history, but just some parts of it, and you will see what happens. At best, you will be accused by society, the scientific community, and colleagues, and you will be fired and stripped of all titles and reputation. At worst, you will face imprisonment and a lead bullet. Kazakhs today might not believe this to be true. But this was the state of historical science in Soviet times because history was the main tool of ideology.’ A fundamental understanding of this truth drove the scholar to work tirelessly for the benefit of Kazakh spirituality and create valuable works.

The other pieces included in A One-Page Story of Qondyger allow the reader to understand the Kazakh worldview through Asemkulov writings for the Kazakh ethnocultural dictionary, his reflections on the great küishi Tattimbet, legends about legends, and critical works on novels and poems.

The book A One-Page Story of Qondyger is kindly provided by Meloman Bookstore.

Book cover of A One-Page Story of Qondyger/From open sources