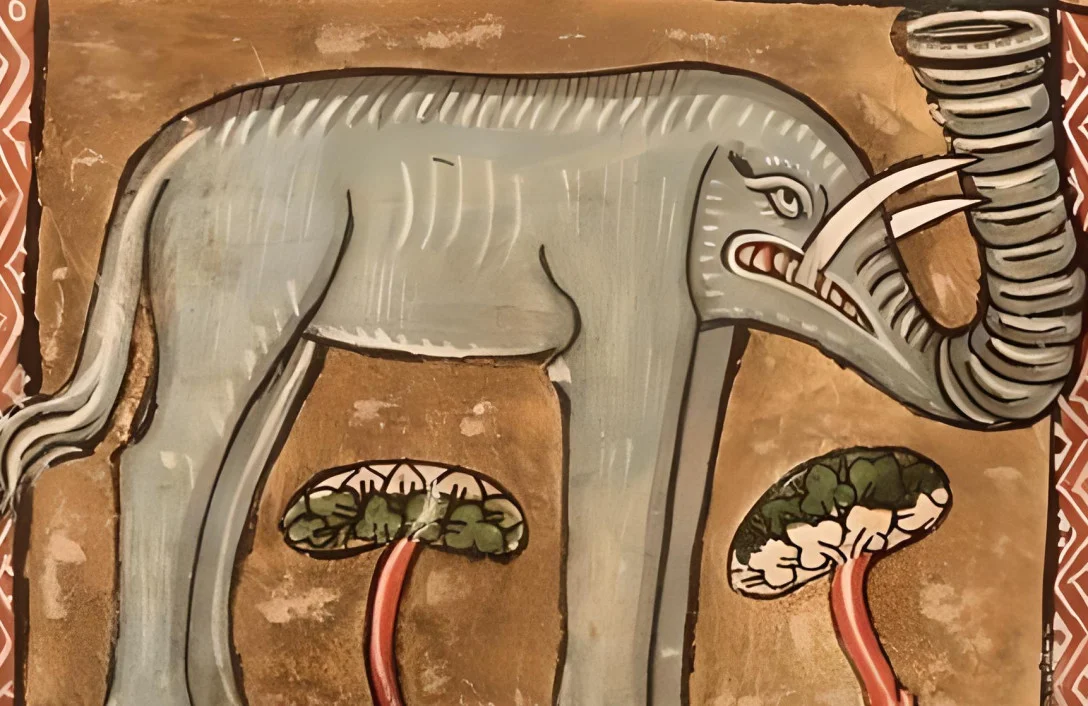

It may seem difficult to believe, but for the medieval European commoner, elephants remained exotic, almost mythical, creatures for a very, very long time. Despite the Europeans’ deep familiarity with them in antiquity, the knowledge of elephants all but disappeared in the subsequent eras, leaving behind only rumors and speculations. If you just look at medieval bestiaries, you'll see that most authors had a very vague idea of the great animal's appearance. Only the depictions of the elephant’s distinctive tusks, well-known to affluent Europeans, remained constant due to imports of ivory from the East.

Fresco. Elephant and castle. 12th century/Wikimedia Commons

Legend has it that it was one such tusk that played a pivotal role in inspiring the journey made by the subject of this article—Abul-Abbas the elephant—to Europe. It was the early ninth century, when Abul-Abbas found himself at the court of the Frankish ruler Charlemagne (768–814), serving as a reminder to Europeans of how these exotic creatures truly looked. The Frankish king supposedly received an elephant tusk as a gift from a merchant and, impressed by its size, wanted to acquire an elephant for his menagerie.

Many sources agree that Abul-Abbas was a gift to Charlemagne from the renowned Baghdad caliph Harun al-Rashid (786–809). However, mentions of this offering appear only in texts of Frankish origin, while Arabic sources are rather silent about any connections between the caliph and Charlemagne's realm. Perhaps the reason lies in the fact that the Arab ruler simply didn't consider King Charlemagne equal in status, and thus, the episode didn't find a place in Eastern records. None of the Frankish sources provide definitive information about the species to which Abul-Abbas belonged or his appearance. The popular assumption that the animal was an albino is supported by illustrations, but it is not confirmed by any authoritative documents.

The Annales Laurissenses Maiores (Greater Lorsch Annals), or the Royal Frankish Annals, stand out as the most notable Frankish source that mentions Abul-Abbas. In the entries for the year 801, these annals chronicle the journey taken by the famous elephant before it arrived at Charlemagne's residence in Aachen. Accompanying the elephant was Isaac, a Frankish Jew who had been sent to the East several years earlier. This Isaac appears to have been the lone survivor among three Frankish envoys who undertook a diplomatic mission to the court of the Arab caliph. Abul-Abbas and his companion embarked on a lengthy and intricate route that spanned the Sinai Peninsula, Egypt, and Ifriqiya (modern-day Tunisia), and they sailed to Europe from the port of Carthage. Their journey to Charlemagne's favored palace in Aachen lasted more than a year, and nearly five years had passed since the embassy was dispatched to Harun al-Rashid with Isaac as part of the delegation. During that period, Charlemagne had ascended to a higher status, being crowned the emperor of the revived Western Roman Empire in the year 800.

Regrettably, detailed information about Abul-Abbas's life at court is scarce. However, some fragmentary records suggest that the elephant was no ordinary resident of the royal menagerie. This exotic creature soon became Charlemagne's favorite and even accompanied him on some military campaigns. The Frankish state during the Carolingian era actively pursued a policy of conquest, and Charlemagne himself often engaged in battle, implying that the potential range of the Baghdadi guest's travels could have been quite extensive. Some authors go further and speculate that the Frankish emperor might have utilized his pet for military purposes, although these assumptions lack concrete evidence.

In the year 810, the emperor embarked on another war, and his new adversary was the Danish king Godfrid, who frequently threatened the neighboring land of Frisia. However, shortly after crossing the Rhine with the emperor's troops, Abul-Abbas fell ill and died suddenly. Determining the exact cause of death for the first elephant of European medieval times remains challenging. Nonetheless, it is known that cattle plague epidemics were prevalent on the Continent during that era. The Annals place the animal's demise at ‘Lippeham’, which has now been identified as near the mouth of the River Lippe, not far from modern-day Vesele. This version has gained support from several findings of elephant bones dating from this era. However, asserting with certainty that these remains belong to the renowned Abul-Abbas remains elusive.

The presence of Abul-Abbas at Charlemagne's court did not mark the start of the widespread imports of elephants into Europe. The next representative of this species would only make its appearance on the continent four centuries later. The Chronica Majora (Great Chronicle) by Matthew Paris describes an elephant's participation in the Cremona Triumph of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (1212–50). Intriguingly, this creature also seemed to be a diplomatic offering, this time from the Egyptian Sultan al-Kamil. However, Europe truly became acquainted with these majestic creatures only with the onset of the Age of Great Discoveries.

Ivory horn "Oliphant" . 1000 year/Alamy