One of the oldest cities in the world, the cradle of classical art and philosophy, Athens can both entirely captivate and bitterly disappoint a traveler. It all depends on your expectations when you leave the gates of Athens Airport Eleftherios Venizelos.

The ancient Hellenes had a saying, which is attributed to the sarcastic, witty playwright Aristophanes,1

Athenian antiquity not only resides but also comes to life in places as majestic and textbook as the Acropolis or the Tower of the Winds. It is present in the fabric of the city, on the streets you walk. Every Athenian knows that the marble plaster in the mosque of Dizdar Mustafa Ağai

It should be noted that ancient structures often served as material for later buildings, but there have been times when new buildings have sheltered old monuments and preserved their traditions. Take, for example, the small church of St. John Around the Column, hidden among the new buildings on Evripidou Street. It protects the remains of an ancient temple whose only surviving column grows through the church’s tiled roof. According to one version, the temple was dedicated to Asclepius, the god of healing, whom the Athenians prayed to for the recovery of their sick. Another interpretation links the building to the Scythian healer Toxaris, who helped the Athenians cope with the plague that broke out during the war with Sparta. Understanding the germicidal properties of wine, he recommended washing the streets of the city with it, and since that time, the Athenians have honored him as a hero.i

Church of Ayios Ioannis Stin Kolona, Athens/Dan/Flickr

It is in such places that the true face of Athens begins to reveal itself—not in the austere city of white stone dreamed of by Europeans fascinated by the classics, nor in the ‘oriental bazaar’ that the hurried and superficial traveler complains about. This city is a living illustration of the words of Heraclitus:i

The Parthenon temple is seen on the skyline of Athens, Greece, on Friday, June 15, 2012. Greeks head to the ballot box in two days for a contest that may determine the fate of the world's first democracy and the future of the newest reserve currency, while roiling markets from Wellington to Wall Street/Chris Ratcliffe/Getty Images

Roots of the Olive Tree

Athens is mentioned several times in the Iliad and the Odyssey. Interestingly, in Homeric times, the city was called ‘Athena’ (Ἀθήνη), after its patron goddess. The plural Athens (Ἀθῆναι) was introduced several centuries later, probably drawing inspiration from other Greek cities such as Mycenae or Delphi. It was retained until the 1976 language reform, and in current Greek, the singular has once again become common. Thus, the first mention of Athens is as old as Greek literature. But it is impossible to say what events took place during the founding of the city. What is clear is that its history goes back more than three or even four millennia.

Antimenes Painter. Olive gathering/British Museum

The rocky hill of the Acropolis,i

Female statuette of Sparta Marble sculpture. Athenes, National Archaeological Museum. Neolithic period, 6000-5000 BC/National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece

During the Early and Middle Bronze ages (3200–1600 BCE), the population of the area increased, and some outlines and even neighborhoods of the future Athens began to emerge gradually. The first burial sites appeared in the area where the beautiful and rich Kerameikos cemetery was established.i

Kerameikos, Ancient Cemetery of Athens, Greece/Alamy

In the eighteenth century BCE, the first wave of Greek conquerors invaded the Balkan Peninsula. They called themselves the Achaeans, but another name often found in historical literature is the Mycenaeans, in honor of the most famous of the cities they built. Warlike, brave, and power hungry, the Achaeans possessed a refined aesthetic sense and a great talent for adopting the achievements of more advanced peoples. Their links with Minoan Crete, Egypt, and the Hittite Empire allowed them to enrich their own culture and create impregnable fortresses, majestic tombs, palaces, and temples.

The arrival of the Achaeans in Attica changed the way of life in that place. The rock of the Acropolis became a royal citadel. To the southeast of the Propylaia (front entrance of the Acropolis), you can still see the remains of the original fortress made of huge blocks of stone. The citadel was surrounded by workshops, warehouses, merchants’ shops, and citizens’ houses. The Mycenaean civilization gave Athens the structure and status of a full-fledged city and since then, its historical path as an important cultural and economic center was predetermined.

Patrons and Kings

The myth of the founding of Athens is as complex and confusing as the history of the city itself. Who should be considered the founder of the city? There are many contenders. King Actaeus, after whom the region of Attica was named? His son-in-law Cecrops, depicted as a half-man, half-serpent (according to legend, he taught the Athenians to read and write and gave them wedding and funeral rites)? Or perhaps Erichthonius, the son of the earth goddess Gaia and the fire god Hephaestus? The Athenians themselves did not have a clear answer to this question. In their perception, the city’s sacred history was not linear and well defined. Many different beliefs coexisted peacefully as the remnants of indigenous tribes did with the Greek settlers.

Cecrops (Ancient Greek: Κέκροψ, Kékrops; gen.: Κέκροπος) was a mythical king of Athens who is said to have reigned for fifty-six years/Alamy

But all the myths gravitated toward one central image: that of the mother goddess. Athena argued with Poseidon about who the patron of the city would be. An agreement was struck according to which the winner was the one who gave the most useful gift to the inhabitants. Poseidon produced a salty spring from a cliff. Athena stuck her spear into the ground and it turned into an olive tree. Of course, the king of Athens chose the olive tree, recognizing the supremacy of the goddess. The story makes rational sense: olive growing was the basis of the Athenian economy. But there are no myths whose meaning is limited to only crude allegory. Athena’s victory also symbolized the mystical triumph of the feminine over the masculine, of life over destruction, of harmony over chaos.

The Night Before Dawn

Mycenaean rule gave Athens a developed culture, fortification, trade links, a written language, a name, and the foundations of identity. But in the thirteenth century BCE, processes that led to the decline of the Achaean civilization began in the eastern Mediterranean, the nature of which is still debated. Archeologists can see their consequences—destroyed cities, a decline in the quality of utensils, the appearance of new types of pottery and weapons—but it is difficult to determine the exact cause. A new wave of conquerors, the Dorian Greeks, was advancing from the north, and the mysterious ‘Sea Peoples’—apparently barbarian tribes that plundered rich coastal states—were attacking from the south, while the Achaean cities were unable to unite against the invaders.

The Dipylon Amphora, mid-8th century BC/National Archaeological Museum, Athens

In the face of this crisis, Athens was more fortunate than other regions: the city was not ravaged and destroyed, but still, the period from 1250 to 900 BCE is characterized by an extreme paucity of archeological evidence. This period is sometimes referred to as the ‘Dark Ages’ of Greek history. But in the eighth century BCE, monumental construction began to take place again. Atop the Acropolis, a small temple dedicated to Athena was built on the site of an abandoned Mycenaean palace. The city was gradually revitalized, and the features that would later make it famous began to emerge.

The seventh century BCE was marked by the abolition of royal power in Athens, and it was a time of reform and upheaval. At first, it seemed as if the city was on its way to democratization. Athens was governed by nine archons (meaning ‘rulers’) and a council (boule). But in 560 BCE, Athens had already become a monarchy again. The tyrant Pisistratus seized power in the city, and having received a detachment of so-called ‘clubmen’,i

The Temple of Olympian Zeus. Olympieion, Athens, Greece/Alamy

After the death of Pisistratus, his sons Hipparchus and Hippias came to power. The former was assassinated by the champions of democracy in 514, and the latter was expelled four years later with the support of the Spartan king Cleomenes. Athens became a republic again, entering a new era of cultural prosperity.

A Flower from the Ashes

In the history of every civilization, there are periods of remarkable harmony and flourishing, periods when a culture is given the chance to reach its full potential in every sphere available to it. For a brief time, the divisions and boundaries between science, religion, politics, and art are blurred. Geniuses have the opportunity to realize their visions, and society becomes more sensitive to their work. Such periods are not cloudless. On the contrary, they are often accompanied by war and feuds. But the flower of culture that grows in the midst of fire and smoke is often stronger than any catastrophe. Such was the culture of Athenian democracy, a flower that blossomed in spite of (or thanks to) the wars with the Persian Empire, whose army invaded the Greek mainland in 492 BCE. The engagements with the Persians on the battlefield became the myth, the ‘heroic age’ that Athenian society had lacked in realizing its potential. It is not without reason that Aeschylus, the writer of great tragedies, mentioned not his literary work, not the awards he received in the theater, but his participation in the Battle of Marathon with the Persians in his own epitaph:

In Gela, rich in wheat, he died, and lies beneath this stone:

Aeschylus the Athenian, son of Euphorion.

His valor, tried and proved, the mead of Marathon can tell,

The long‐haired Persian also, who knows it all too well.i

Today, Marathon is a picturesque, green suburb of Athens. The only reminder of the battle that took place here in September 490 BCE, when the Athenians, in an alliance with their neighbors the Plataeans, defeated a huge Persian army, is an exhibition in the museum and a mound that guides often call a mass grave of Greek soldiers. However, the mound is a structure from Roman times in fact. Marathon was the home of the famous orator of the second-century CE Herodes Atticus, who spent much of his vast wealth beautifying Athens and its environs. Apparently, he felt it was his duty to honor his countrymen and erected a monument in their honor, of which this mound remains. As for the actual graves, the soldiers who fell at Marathon were not buried in mass graves, but in individual tombs.

Ten years after the Battle of Marathon, in 480 BCE, the Persian king Xerxes I launched a new campaign against Greece. After defeating the Spartan army at Thermopylae, the Persians came dangerously close to Athens. The city’s inhabitants had to be evacuated, but most were reluctant to leave their homes. To persuade them, the Athenian strategosi

The war continued for several years. Led by the Athenians, the Greeks drove the Persians from their land. And by the time peace came, Athenian society had already entered a period of creative growth. The struggle for freedom, however, had hardened the Athenians, strengthened their sense of citizenship, and made them think more seriously about the religion and customs of their ancestors. Playwrights, philosophers, painters, sculptors, and poets all tried to understand what had happened and to find answers to the eternal questions of honor, justice, and humanity. Only construction, the most expensive and labor-intensive field, lagged behind.

Battle of Salamis Italiano: La Battaglia di Salamina 1868/Wikimedia Commons

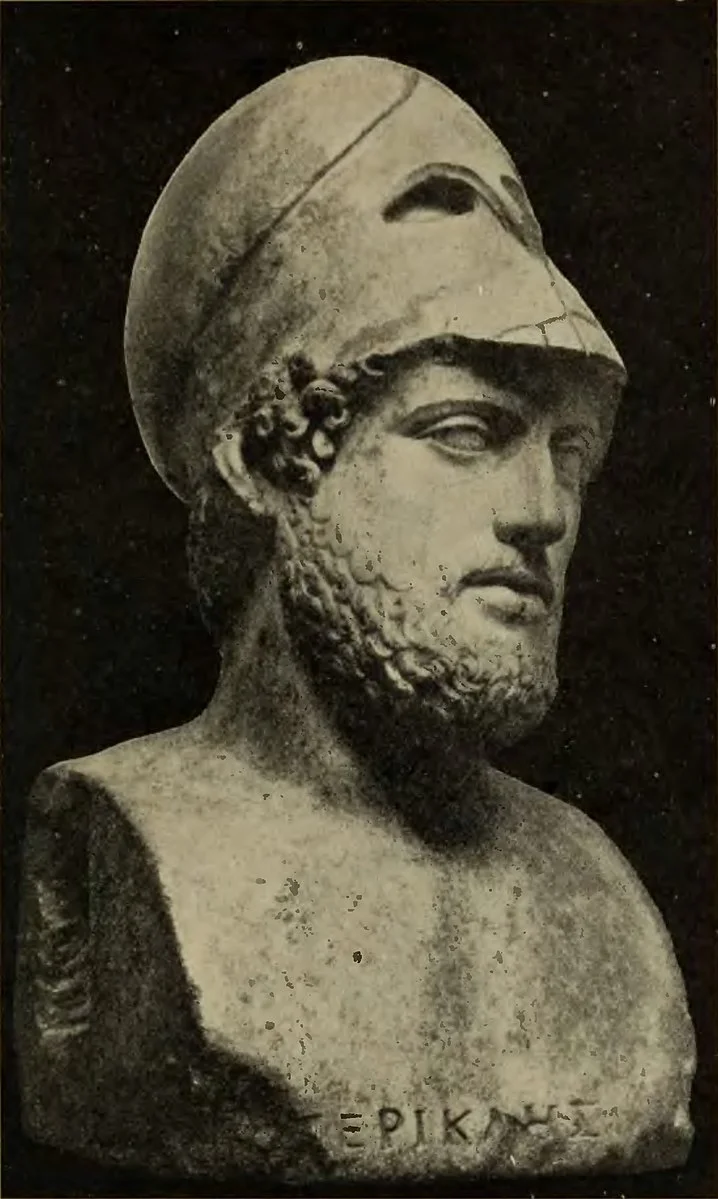

As a free city, Athens lay in ruins. Reconstruction required a clear plan and ample funding. Thus, in 472 BCE, the Athenian public was presented the tragedy The Persians, written by Aeschylus. The playwright was sponsored by the noble Athenian Pericles, son of Xanthippus, an ambitious young politician and patron of the arts. A few years later, in 464 BCE, he successfully ran for strategos and began grandiose reforms, one of the most important of which was the rebuilding of the city. The most talented craftsmen were recruited, and Phidias, a brilliant sculptor with an excellent grasp of all aspects of urban planning, was entrusted with supervising them. For the first time in its history, the Acropolis became a cohesive whole, with each element harmoniously integrated with all other details. The composition of the ensemble was inspired by the Athenian religion itself.

Bust of Pericles in the British Museum./British Museum

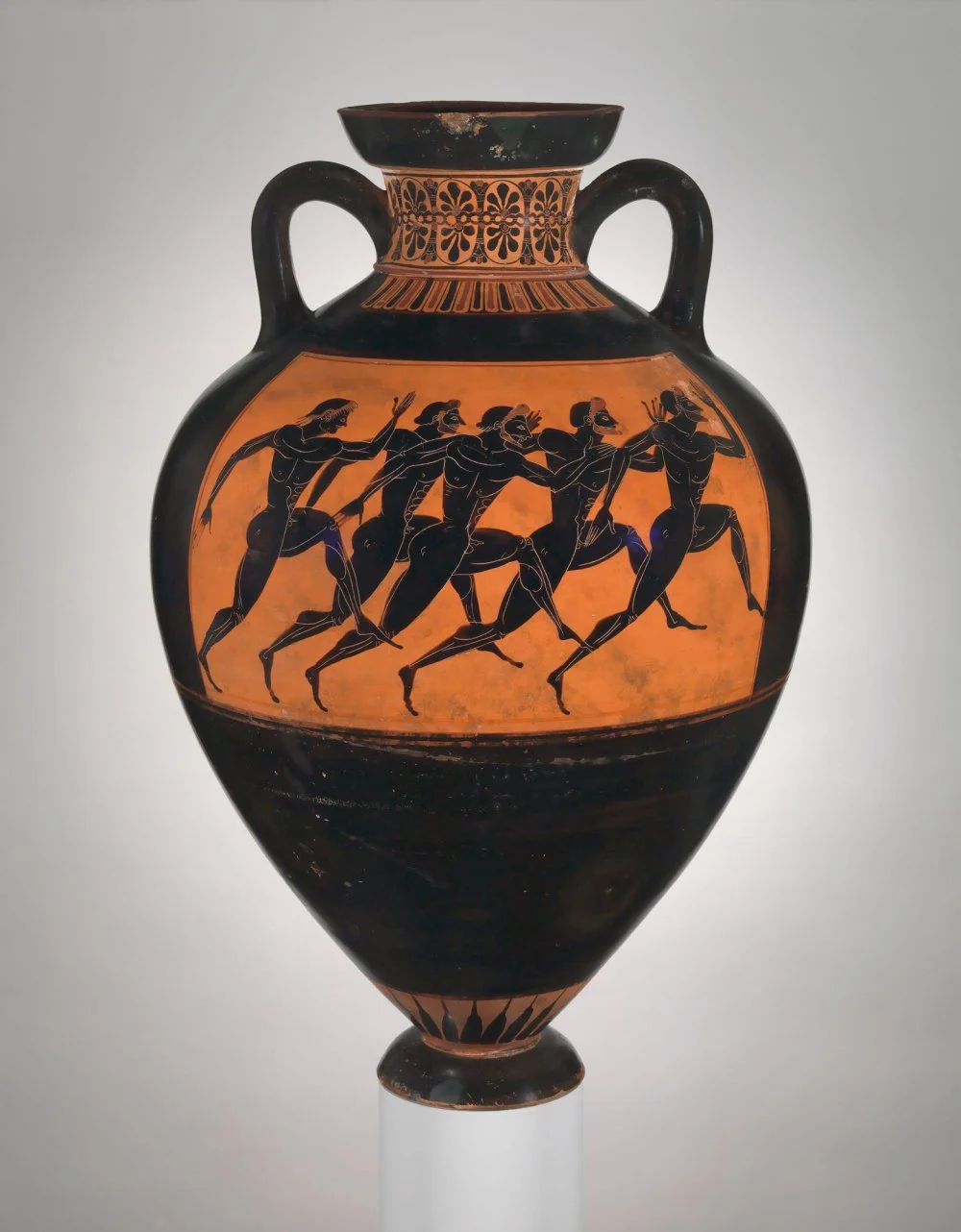

The most important city festival was the Panathenaia, the annual celebration of Athena. The first days of the festival were devoted to athletic and artistic competitions and on the last day, a great procession moved through the center of the city, from Kerameikos to the Acropolis and up to the temples, in which all citizens participated without exception.

Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora. Attributed to the Euphiletos Painter. ca. 530 BCE/Alamy

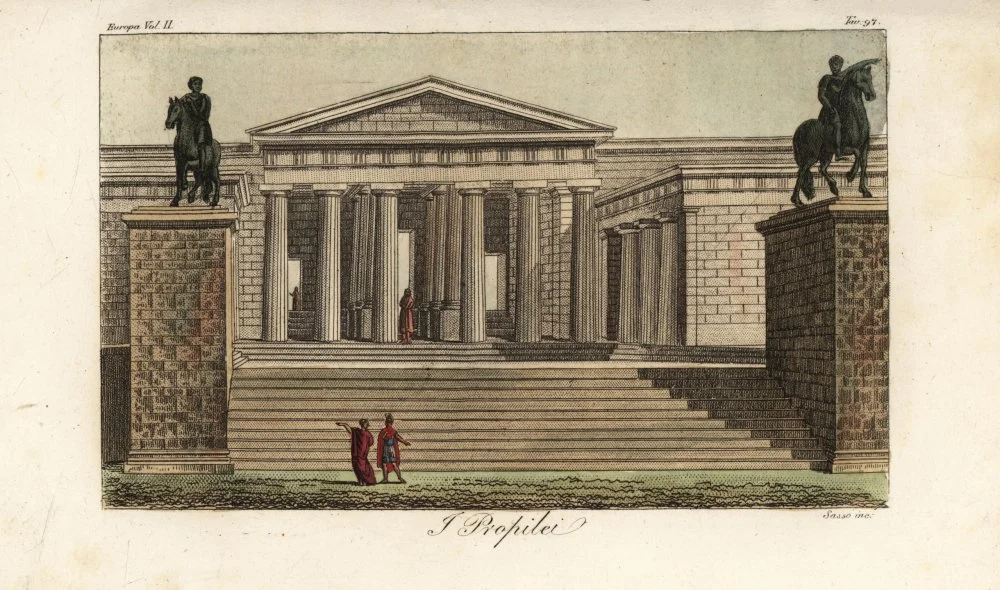

The statue of the goddess was dressed in a sacred garment woven by Athenian girls, and then the priests made a sacrifice at the altar and threw open a public feast. Architects invited by Pericles reproduced this ritual in stone. The main gate of the Acropolis was now the Propylaia, a monumental portal for the passage of people and sacrificial animals.i

Reconstruction of the Propylaeum in Athens, 1826/Getty Images

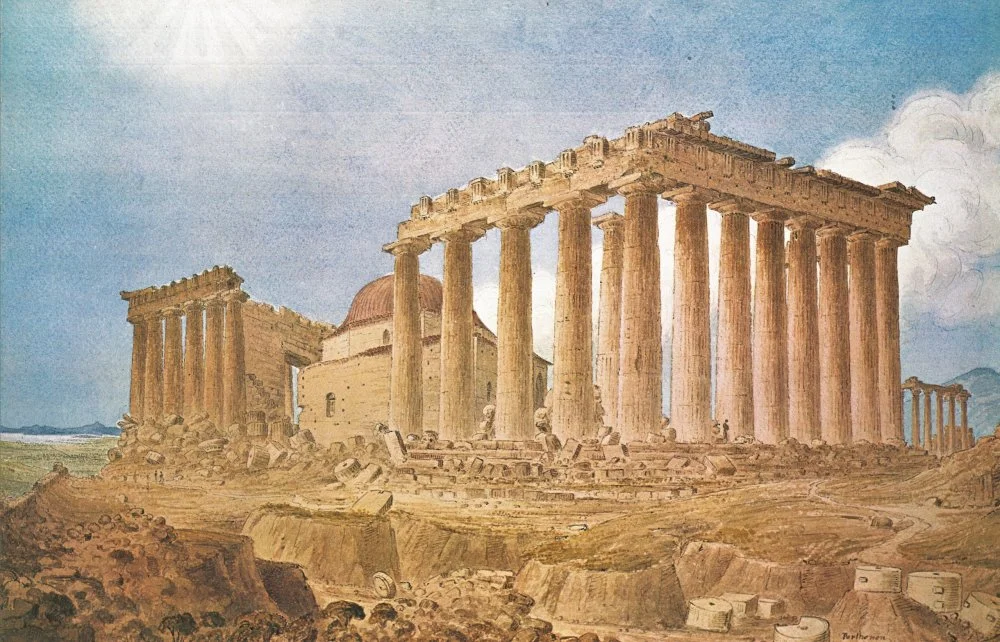

The most famous of these is the Temple of Athena, built by the architects Ictinus and Callicrates. It is known to the general public as the Parthenon, which means ‘the chambers of the Virgin’, but this name was originally applied only to one of its rooms (most likely the one containing the statue of the goddess). Mighty and weightless at the same time, radiating tenderness and heroic aloofness, the Parthenon is rightly considered the benchmark of the Doric order (another of Ictinus’s works, the Temple of Apollo in Bassae, Messenia, could be compared to it, but it is not as well preserved). According to classical architectural tradition, the Doric order is a symbol of courage, and this fit perfectly with the image of the warrior goddess.

James Skene. The Parthenon from the southeast. 1838/Wikimedia Commons

The nearby Erechtheion, on the other hand, embodied all the elegance of the Ionic order, which was considered a symbol of femininity. The figures of young priestess-caryatids, supporting the overlap of the southern portico, humanized and completed this symbolism.

The Parthenon was dedicated to the heavenly hypostasis of Athena, while the Erechtheion glorified the chthonic, earthly essence of the goddess, and with her—the ‘earthshaker’ Poseidon, Hephaestus with his subterranean fire, and the legendary king-parents Cecrops and Erichthonius. The architects conveyed these central religious themes with the help of the classical order. In addition, all the theological and ritual details that Athenians had to keep in mind were depicted on the pediments and friezes of the temples.

The Erechtheion is an ancient Greek temple built between 421 and 406 BC on the north side of the Acropolis of Athens/Alamy

During the rule of Pericles, many other magnificent buildings were erected. The city flourished before the very eyes of its citizens. But the uniqueness of this golden age did not lie in the fact that Pericles managed to build so many structures in such a short time, but in how graceful and harmonious they were, even by strict classical standards. ‘Such is the bloom of perpetual newness, as it were, upon these works of his, which makes them ever to look untouched by time, as though the unfaltering breath of an ageless spirit has been infused into them’.i

Unattainable Freedom

The long-awaited Athenian military confrontation with Sparta began in 431 BCE. The Peloponnesian War lasted twenty-seven years and claimed many lives on both sides. The plague epidemic that broke out in 430 BCE killed Pericles and many others.i

Lysander outside the walls of Athens, ordering their destruction. 19th century lithograph/Wikimedia Commons

The city lost its political freedom, but the enormous cultural wealth accumulated during the democratic period continued to bear fruit. Schools of philosophy and oratory, magnificent theaters and stadiums, vast collections of art, and religious sanctuaries attracted travelers from all parts of the Greek world. The kings of the Macedonian dynasties came to Athens to study, the cream of the aristocracy flocked to Athens, and many visitors considered it their duty to build something in the city. Among the monuments of the Hellenistic period, two stoai (galleries), built a decade apart—in 160 and 150 BCE respectively—by two Pergamon kings, Eumenes II and Attalos II, are particularly impressive. The Stoa of Eumenes, which is not very well preserved, is made of marble from Asia Minor and follows the style developed in Asiatic Greek architecture. The Stoa of Attalos, which was fully restored in the 1950s, has a more ‘local’ appearance. Although it is a recreation of archeological finds, it is one of the most spectacular monuments in Athens. Walking around in its environs allows you not only to admire the ancient architecture but also to experience it physically by walking along the rows of white marble columns and observing the optical illusions they create.

Athens came under Roman rule in 146 BCE, and there was no destruction. But the citizens’ love of freedom—they wanted to regain sovereignty at all costs—played a cruel joke on them. In 87 BCE, when Rome was at war with the powerful Pontic king Mithridates VI, the Athenians appealed to him to liberate them. War broke out all over Greece, and one by one, Greek cities rebelled against Roman rule. The Roman army under the command of Lucius Cornelius Sulla destroyed the rebellious Athens as barbarically as Xerxes. ‘[T]he blood that was shed in the marketplace covered all the Cerameicus inside the Dipylon Gate; nay, many say that it flowed through the gate and deluged the suburb,’ wrote Plutarch.2

This bloody episode was, however, not typical of Athenian-Roman relations. The vast majority of emperors treated the city with the same admiring fondness as Alexander the Great’s successors and invested heavily in it. The chief benefactor of Athens was Hadrian (76–138 CE), an enlightened and deeply religious emperor. Among the monuments of his era surviving in Athens are the Arch of Hadrian,i

Hadrian's gate on a sunny day, Athens historical center, Greece/Shutterstock

The Age of the Brick

In his poetry, Greek poet Giorgos Seferis used a pithy term—‘marbles’ (μάρμαρα)—to recreate the image of ancient Hellas. This symbol embodies the grandeur of ancient Greek cities, reflecting the enduring steadfastness and wisdom propagated by philosophers, mathematicians, and astronomers. But the culture of stone building began to fade in late Roman times, replaced by the cheaper brick (the type of ancient flat brick commonly called plinth). The other achievements of ancient civilization—art, science, technology—also faded. The internal crisis of the Roman Empire, the migration of barbarian tribes, the establishment of the Christian religion, whose proponents did not care about the value of the ‘pagan’ monuments they were destroying, all gradually undermined the marble world, and brick buildings grew on its ruins.

After the fragmentation of the Roman Empire, Athens fell to Byzantium, its eastern part. The Byzantine emperors, who did their best to eradicate the ancient cults, unwittingly destroyed not only the scholarly traditions that had once made the city famous but also many architectural monuments. Emperor Justinian, who ruled from 527 to 565, closed the philosophical schools that remained in the city, and Theodosius II (408–450) ordered the conversion of ancient sanctuaries into churches. The temples of the Acropolis also became churches. The Parthenon was rebuilt into the Church of the Virgin Mary and the Erechtheion into the Church of the Holy Trinity. There is a certain continuity in these reforms—after all, it was the temple of the Virgin Athena that became the temple of the Virgin Mary. Perhaps this was the only way to help citizens accept the new religion, but it had its own cost—the decoration inside the buildings were irretrievably lost. A similar fate befell most of the classical temples, and the construction of new churches and cathedrals began only much later, at the end of the ninth century.

While Athens is not the best city to explore Byzantine architecture as compared to Thessaloniki, where these structures are much better preserved. But the church of Panagia Pantanassa (St. Mary) in Monastiraki, the tiny church of All Saints Confessors (39 Tsokha Street), and the church of St. John the Theologian in Plaka all have a special character inherent to the Greek Middle Ages. Among the churches of Athens, one stands out, and a visit there is a truly fascinating experience for a connoisseur of antiquity. This is the Little Metropolis, formally known as the Church of St. Eleftherios, located in Mitropoleos Square. It is made up of fragments of other buildings and structures, both ancient and medieval. One can distinguish tombstones, sarcophagi, fragments of reliefs in the masonry of its walls. It is also clear that stone blocks were taken from earlier buildings. This is what medieval Athens was, a scattering of ancient fragments reshaped by a changing culture.

The Little Metropolis/Shutterstock

In 1205, the city was taken by crusaders,i

Daphni monastery in Athens Greece - religious greek landmarks/Shutterstock

From Turban to Crown

In May 1453, the army of Sultan Mehmed II the Conqueror captured Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. Three years later, in 1456, the Turks took Athens without a fight: the Duke of Athens sought refuge on the Acropolis but surrendered two years later. In 1458, the triumphant sultan visited the city. He came not as a conqueror but as a pilgrim to admire the Parthenon, which had been rebuilt by then—this time as a mosque. Greek historians note that this rebuilding was done as carefully as the circumstances and spirit of the times allowed.

The Islamization of Athens was slow and bloodless. By the 1520s, the Muslim population numbered no more than ten households. Noble Ottoman families settled on the Acropolis, while the commoners were content with the lower parts of the city. But by the mid- to late sixteenth century, the Ottoman community had grown, and the single mosque could no longer meet its needs. A total of eight mosques were built in Athens during the Ottoman rule (not counting the Parthenon), but only two have survived: the Fethiye Mosque, built in 1670 near the northern part of the Roman Forum, and the mosque of Dizdar Mustafa Ağa, the same one for which the column of the Temple of Zeus was destroyed.

This ancient colonnade, in which both Christians and Muslims saw a kind of ‘place of power’, is linked to a curious episode that vividly illustrates inter-ethnic relations in the city. ‘In the month of March … [a]n extraordinary drought had raised concerns for the Athenians about their future harvest: prayers and holy rites were performed in this place for nine successive days, three of which were devoted particularly to the Mahometans, three to the Christians, and three to the strangers and slaves. The people were collected in the ravine, on the corn fields, and under the columns [near the Temple of Zeus]. The Mahometan priest supplicated for all, and the whole assembly, of all conditions and persuasions, were supposed to join in the prayers.’i

Indeed, the Athenian Greeks had much better relations with the Ottomans than with the Latins. Although episodes of mutual violence, sometimes brutal, were not uncommon in the Ottoman Empire, Christians and Muslims got along well as neighbors in Athens. Perhaps this was due to the tranquility of the city, away from political strife. The benevolence of the sultans, who treated Athens with special sympathy, also likely played a decisive role. In any case, during Ottoman rule, the city suffered the most at the hands of its European neighbors and not the Turks.

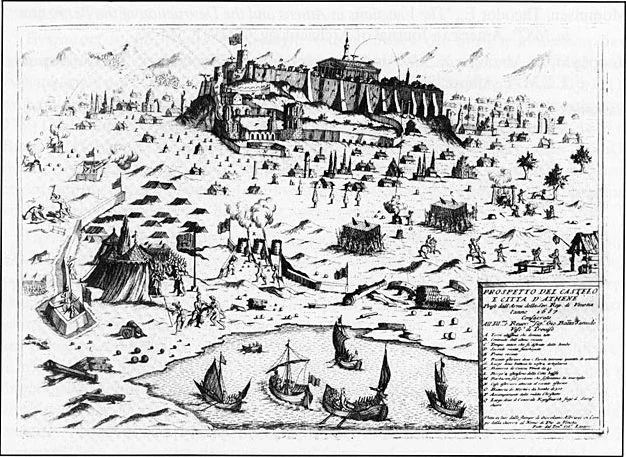

The period from 1683 to 1699 was marked by a series of wars between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League, an alliance of European Christian states. During a battle in September 1687, the allied army blockaded Athens from the sea, landed on the shore, and began bombarding the fortifications, focusing on the Acropolis. The Turks, relying on the mighty walls of the Parthenon and divine protection—it was, after all, a mosque for them— hid powder supplies, children, and women inside. Soon, cannonballs broke the roof open, and the barrels of gunpowder exploded. All the people in the Parthenon were killed, the explosion causing enormous damage to the temple. Characteristically, the commander of the allied forces, the Venetian Francesco Morosini, did not see the event as a catastrophe—it was an excuse to loot the Parthenon. In an attempt to remove the surviving sculptures from the western pediment, the soldiers dropped and smashed them.

Depiction of the Venetian siege of the Acropolis of Athens in 1687, during the Turkish-Venetian War/Wikimedia Commons

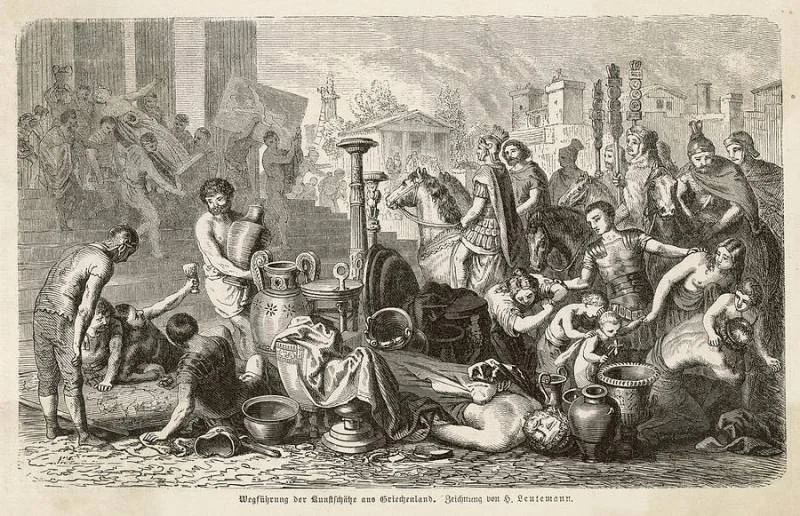

Soon, the peaceful looting of antiquities began. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European nobility was obsessed with ancient history. This fascination not only helped create outstanding archeologists, but it also engendered thieves who traveled to Athens to snatch some vase or sculpture and sell it at the highest possible price. Nobles did not shy away from pilfering treasures either. In 1801, the British diplomat Thomas Bruce, the seventh Earl of Elgin, cleverly manipulated a sultan’s firman (letter of permission), allowing him to export some ‘ancient stones’ from the Acropolis to England, thus seizing the most valuable statues and reliefs. Of course, Bruce claimed that he was trying to ‘save’ these masterpieces from the local ‘barbarians’ who would surely destroy them. Lord Byron, who loved Greece fiercely and understood the diplomat’s true intentions, made a scathing commentary on the events in the second canto of his Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage:

But who, of all the plunderers of yon fane

On high, where Pallas linger’d, loth to flee

The latest relic of her ancient reign;

The last, the worst, dull spoiler, who was he?

Blush, Caledonia! such thy son could be!

Meanwhile, a popular liberation movement was gradually sweeping across Greece. It had begun as a spontaneous activity of guerrilla groups, but by the 1820s, it had developed into a full-fledged revolutionary struggle. In March 1821, a nationwide uprising had erupted, and Athens became one of the first cities to raise the Christian white and blue flag. By 28 April, most of the city had been taken by the rebels, and only the Ottomans, who had taken refuge on the Acropolis, continued to resist. The value of this victory was largely symbolic: the city changed hands several times during the war, which lasted three more years, but Athenians still cherish its memory. In 1834, Athens was declared the capital of the Kingdom of Greece.

Theodoros Vryzakis. The Bishop of Old Patras Germanos Blesses the Flag of Revolution (detail). 1865/ Wikimedia Commons

New Myths

Nineteenth-century Athens struggled to distance itself from its Ottoman past and become more European. Most Turkish monuments were destroyed, replaced by neoclassical buildings based on the German, French, and Italian models. But even this European influence would not last more than a century. The twentieth century stripped Athens of its pretensions in the crudest possible way, allowing the city to spontaneously and chaotically sprawl, boasting an insane mix of styles and eras. The massive destruction of ancient buildings during the term of president Konstantinos Karamanlis (1955–63) robbed Greek cities of their architectural identities. Today, they look like clusters of prefabs, with the odd, solitary villa dotting the landscape every now and then. Athens did not escape this vandalism, although it suffered less than, for example, Thessaloniki or Patra. Moreover, most of the surviving buildings are in a poor state of repair, and their confusing legal status prevents restoration.

Skyline of Athens, Greece/Alamy

But the Greek capital has so many distinct, enduring features that the standard housing development board could not rob the city of its charm. The green massif of Hymettus in the east, the stony Pentelikon in the southwest, the rock of the Acropolis in the center—disappearing behind houses and reappearing in the streets like a fantastic airship—numerous hills and cliffs, all give the city landscape a solemn beauty. Moreover, after speaking to people who have lived here a long time, it seems that the old Athenian way of life has not disappeared but has retreated into the same fairyland as antiquity.

Athenians still remember the façades of demolished houses, the routes of the trams (the rails were dismantled in the 1960s), the names of street vendors, the menus of long-closed restaurants. Lines such as these below reassure of us of this:

Sparks from the wires,

Around the corner on the street with the caryatids

Were spinning

Cracking

Streetcars

On vacant lots the sun scratched

Thickets of nettles and brambles.

These lines are from a poem written by the modern Greek poet Odysseas Elytis. He was probably referring to the Agion Asomaton (meaning the ‘holy bodiless’ or ‘holy uncorporeal ones’), a street that received its unusual name from the Byzantine temple of the same name. The villa with figures of caryatids, the work of architect Ernst Ziller, has been preserved to this day. In addition to this world of memory, there is another world of gruesome stories that reflect the darkest layers of the city’s history. It is said that the abandoned tuberculosis hospital on Mount Parnitha is full of ghosts, and the sounds of the devil’s dance can be heard from the morgue at night. It also said that the souls of townspeople tortured by the Gestapo haunt the Villa Kazoulis, which served as a Schutzstaffel (SS) command post during the occupation of Greece during the Second World War.

In the Davelis Cave, on the southeastern slope of Penteli, it is said that something mystical happens all the time: some people have seen balls of lightning, some ghosts, and some tornadoes. It is rumored that local satanists also hold their unholy rites there.

Symposium

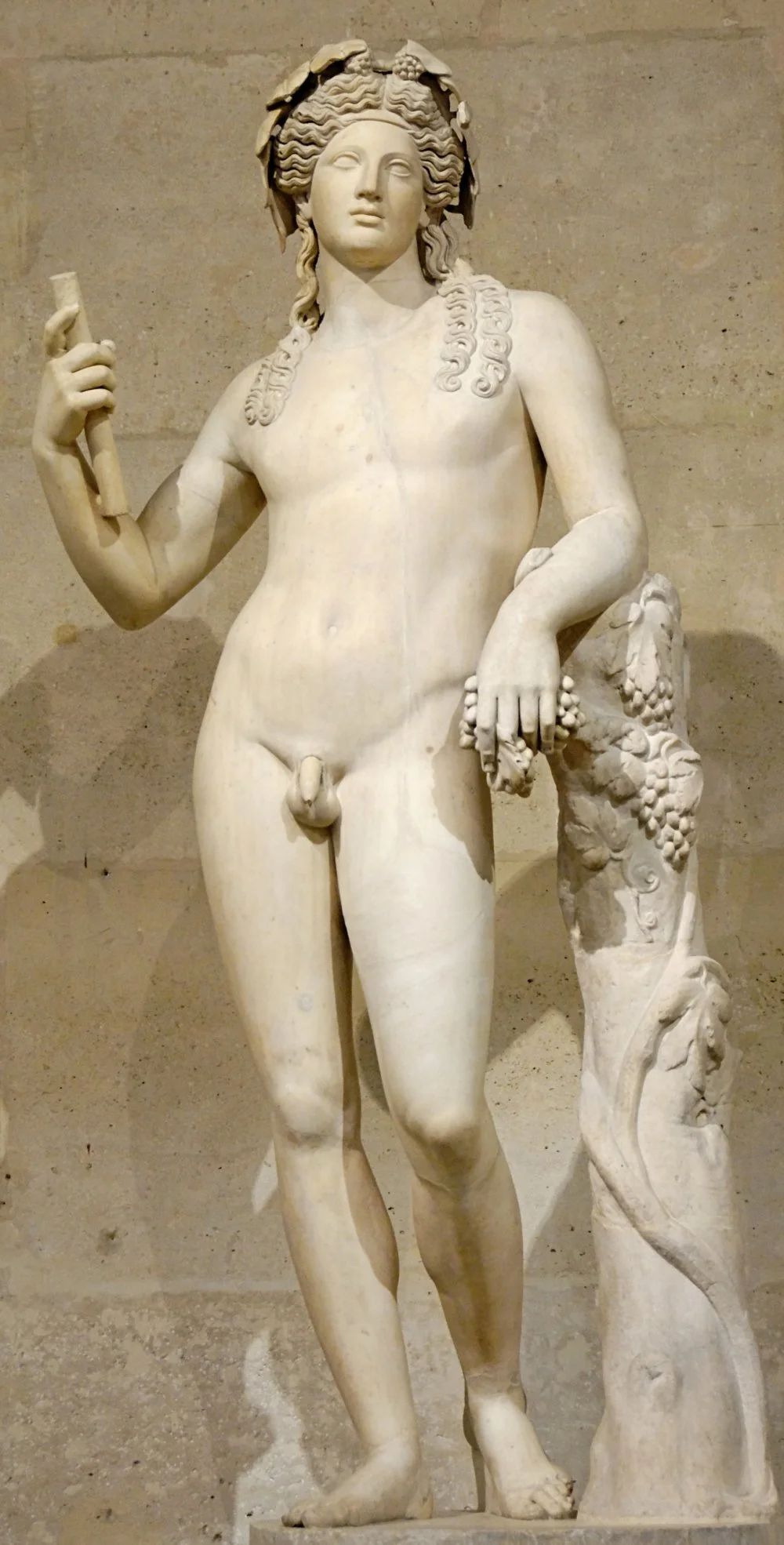

The symposium, or feast, was the center of social and personal life for the ancient Athenians. At feasts, they offered libations to the gods, shared their plans and accomplishments with friends, and discussed politics and learning. They sang songs, embraced courtesans, told stories and anecdotes, and drank excessively, and scenes like these are depicted on many Attic cups. At the same feasts, they read beautiful poetry and pondered philosophical theories—the high and the mundane aspects of life were united in one life-loving impulse. Reflections of these customs have survived among modern Athenians, and there are several neighborhoods where citizens traditionally gather to praise Dionysus over a shot of rakia or a glass of wine.

Statue romaine de Dionysos/Wikimedia Commons

The areas of Monastiraki and Plaka attract middle-aged and older people. There are many tavernas in the area catering to tourists (the high prices and the sirtaki blaring from the loudspeakers are a clear sign), but there are also many places catering to locals. Some of them have a curious history, such as the Old Psarras Tavern, where Vivien Leigh and Graham Greene enjoyed their meals, or the Platanos Tavern, a popular meeting place for Athens’ literati.

People who love a ‘European’ atmosphere prefer cocktail bars tucked away in the nooks and crannies of the city. Couleur Locale in the Norman Street Gallery in Monastiraki looks modest and unassuming, but its terrace offers a truly unique view of the Acropolis.

For the young, the city has another ‘symposium hall’—the Exarcheia district. This area is chaotic, messy, and not populated with fashionable hotels and expensive shops, but it has a cozy and colorful character of its own. Its proximity to the National Technical University determined its fate. In the mid-twentieth century, Exarcheia became the center of the protest movement and radical art. It was here that the 1973 uprising against the colonels’ junta began. The Greek rock stars Pavlos Sidiropoulos and Nikolas Asimos, the poet Katerina Gogou—often informally referred to in the Greek community as ‘the saints of Exarcheia’— the actor Dimitris Horn, and many other notable and eccentric personalities have lived here. Glitz and glamor are not a part of the ethos of Exarcheia, but in its cramped bars you can hear all kinds of extreme music, from metal to noise, the art of young artists and photographers. And who knows, at the next table you might see a famous composer or singer.

Colorful umbrellas of a public market in Athens, Greece 30 December 2023, Athens, Greece: This is a photo of a public market in Exarchia neighborhood of Athens, Greece/George Pachantouris/Getty Images

Whether a traveler chooses a traditional tavern in Plaka, a colorful cafe in Exarcheia, the rooftop garden of a five-star hotel, or a seaside restaurant that smells of iodine and oleanders, the city becomes their main interlocutor at the feast. A palette of tastes and smells is added to the palette of colors and textures. It becomes clear that the contrasts and imperfections of Athens are only a form of human nature, and as the ancients used to say, man is the measure of all things. There is also a moment of a profound connection with Athens. It is at this point that one sees in the city not architecture, not landscape, not a cluster of buildings, but ‘a man rising from the core of marble blocks’.i