A little over a hundred years ago, the leaders of the Alash Movement, an early twentieth-century Kazakh nationalist and political effort, tried to convince the world to recognize their new republic. In the turbulent years following the collapse of the Russian Empire, they wrote letters to governments across Europe and Asia, met with diplomats and trade representatives, and did everything possible to preserve Kazakh statehood amid the chaos of revolution and civil war. Today, newly declassified archives from Kazakhstan, Russia, and Japan reveal the remarkable scope and scale of this nearly forgotten diplomacy. In this exclusive discussion with Qalam, Alash scholar and researcher Sultan Khan Akkuly explores how these early visionaries imagined Kazakhstan’s place in the modern world.

- 1. New Evidence from the Era of Alash Orda

- 2. The Mission to Vladivostok: Raimjan Marsekov’s Secret Diplomacy

- 3. The Czechoslovak Corps and Early Military Contacts

- 4. Alash and the West: The Hopes and Calculations of the Great Powers

- 5. Wilson and the East: Diplomacy of the Fourteen Points

- 6. Eastern Focus: The Appeal to Japan

- 7. The Legacy of Alash Orda: Diplomacy Ahead of Its Time

New Evidence from the Era of Alash Orda

Declassified judicial and investigative materials from the archives of Kazakhstani

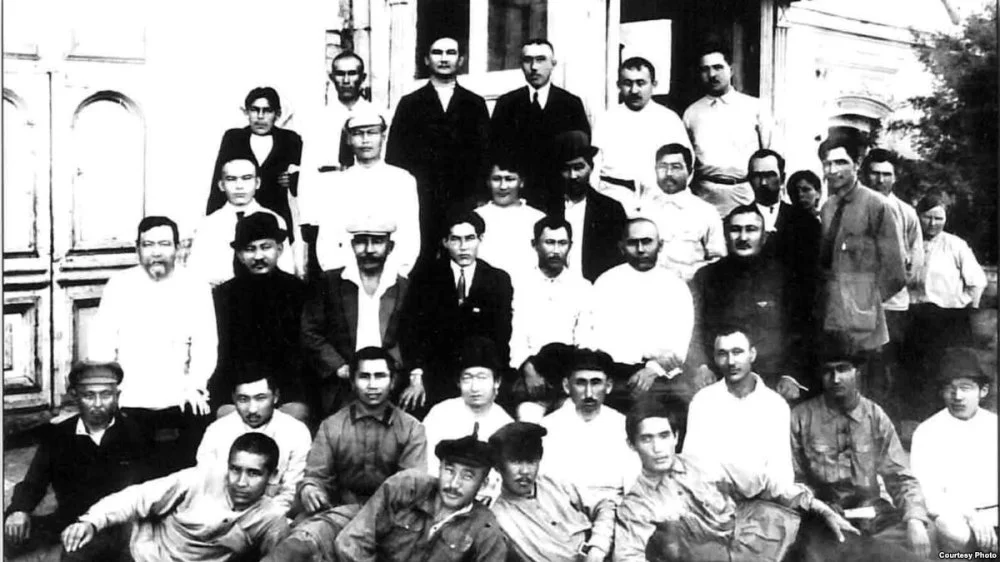

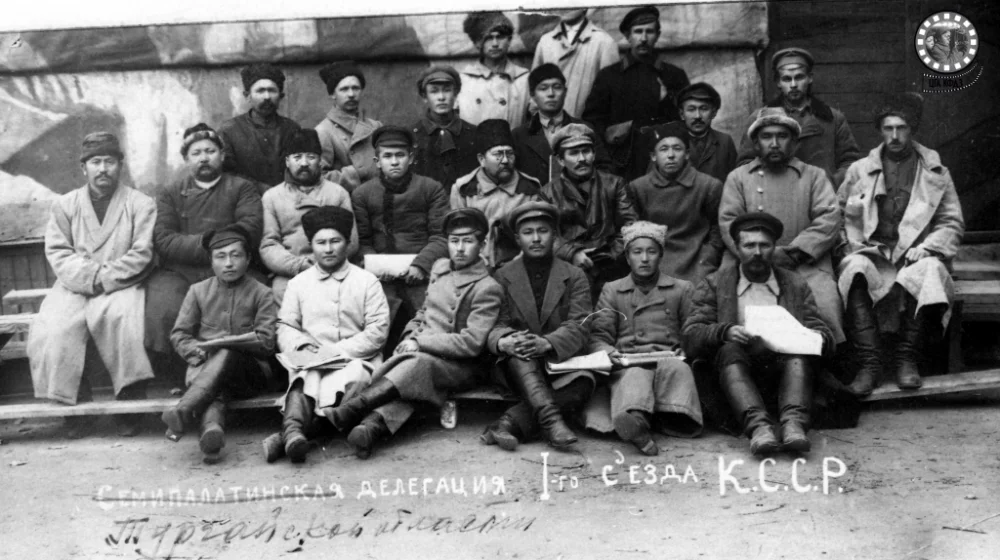

Delegation from Semipalatinsk Oblast at the First Congress of the Kazakh ASSR, 1920. N. Nurmakov — Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Kazakh ASSR; A. Bukeykhanov — one of the founders of the Alash party; A. Yermekov — Deputy Prime Minister of the Alash-Orda government / CSACPA

The Alash Orda Council’s appeal to the Japanese government, which was uncovered by researcher Ryosuke Ono in the archives of Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, together with the 1938 People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (abbreviated as NKVD) testimony of Raimjan Marsekov—a key figure in the Kazakh national movement, member of the Alash Party, and former head of the Semipalatinsk Regional Zemstvo—compel a reassessment of the history of the Alash Republic and the activities of its government between 1918 and 1920.

The focus here is primarily on Marsekov’s trip to Vladivostok, officially presented as a business trip for the regional zemstvo’si

The Mission to Vladivostok: Raimjan Marsekov’s Secret Diplomacy

The officially stated purpose of Raimjan Marsekov’s trip to Vladivostok was to negotiate with foreign companies so that they would supply the regional zemstvo with various goods and household supplies needed by the local population. According to the Saryarqa newspaperi

Arriving in Vladivostok at the beginning of 1919, Marsekov held negotiations with Sir Mayer, who was the head of two American companies: Anderson and Mayer & Co. Based on the newspaper report, we can assume that the discussions concerned not only the purchase of household goods and supplies for the regional population but also the export of Kazakh livestock products to the United States. In his testimony, Marsekov acknowledged only the signing of a contract to supply goods to the zemstvo worth 15 million rubles. It is possible that this involved an exchange of goods of equivalent value.

Raimzhan Marsekov/Wikimedia Commons

In fact, this marked the first—and ultimately the last—instance of truly independent international trade and economic cooperation, not only for the de facto sovereign Alash Republic but also for Soviet Kazakhstan, which emerged after the republic was forcibly dissolved by the Bolsheviks in 1920.

Interestingly, Raimjan Marsekov visited the Czechoslovaki

During the negotiations with the Czechoslovak consul, he stated that no Siberian peoples, including the Kazakhs, wished to be under the rule of Admiral Kolchak, who was the principal White Army leader in Siberia during the Russian Civil War, later captured and executed by the Bolsheviks. According to the leaders of Alash, Kolchak sought the restoration of the monarchy overthrown in Russia, and he urged the consul not to support him.

The Czechoslovak Corps and Early Military Contacts

It would, however, seem quite odd if Marsekov, after traveling several thousand kilometers from the Kazakh steppe to the ‘Far East’, presented himself as the official representative of the Alash Orda Council and met ‘first and foremost’ with the Czechoslovak consul merely to convey his government’s stance on Admiral Kolchak’s authority and to urge the newly independent Czechoslovak government not to support him. According to his own testimony, in all of his official meetings, he requested recognition of the statehood and independence of the Alash Republic and allied Turkic-speaking peoples—such as Turkestan, Bashkiria, and the National Administration of Turkic-Tatars—as well as the establishment of bilateral diplomatic and trade relations and the provision of military and political support.

Support Rally of the Kokand Autonomy. 1917 / Wikimedia Commons

It is likely that, like other leaders of Alash Orda, he did not place great hopes on political support from the Czechoslovak Republic, which had been established only at the very end of the First World War, in October 1918, after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Nevertheless, it was in a position to provide critically important military and technical assistance to Alash Orda in its struggle against Bolshevik intervention, including supplying weapons for its emerging national army.

Troops of the Czechoslovak Corps in Irkutsk. 1918 / Wikimedia Commons

After the Bolsheviks dissolved the All Russian Constituent Assembly in January 1918, Russia lost its legitimate government. In the resulting power vacuum, the Alash Autonomy transformed into a republic exercising full state authority over its territory—that is, sovereignty not constrained by external supra-national (federal) bodies.

Authorized by the Second All-Kazakh Congress that took place between 5 and 13 December 1917 ‘to negotiate blocks (unions, alliances) with other autonomous neighbors’, Alash Orda conducted an independent foreign policy from 1918 to 1920, engaging in negotiations on mutual recognition, military-political alliances, and coordinated resistance against the Bolsheviks.

New documents—both foreign and domestic—demonstrate that during this period, Alash Orda actively sought to reduce dependence on Russia and secure international recognition of its de facto statehood and independence, employing a variety of strategies and tactics. Among the many issues involved in ensuring sovereignty—political, economic, territorial, and socio-cultural—the organization of military defense to protect the country’s independence played a particularly crucial role.

In August 1937, Alikhan Bukeikhan, the former chairman of Alash Orda, recalled that following the decision of the First All-Kazakh Congress (which took place between 21 and 26 July 1917) and the September meeting in Semipalatinsk, the leaders of Alash set out in 1917 to establish the first regular national army in Kazakh history. The first cavalry regiments of the Alash army were formed, trained, and armed even before the military department of the Alash Republic was created, which only came into existence on 24 June 1918 as part of the Alash Orda Council under the name ‘Military Council’. This council was entrusted with the functions and powers of a ministry of war, including the authority to establish military councils in regional and district branches of Alash Orda, and it was responsible for mobilizing Kazakh fighters to combat the Bolsheviks.

A group of former members of the National Council (Government) of Alash Orda and the Alash Party after the dissolution of the Alash Republic and its government, and the establishment of the Kirghiz (Kazakh) ASSR. August 26, 1920, Orenburg. / Courtesy of Sultan Khan Akkuly

This marked the establishment of the first Ministry of Defense in modern Kazakh history. The head of the Military Council, and thus the first minister of defense, was career officer, artilleryman, and First World War veteran Khamit Toktamyshev, who later rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

As stated in Alash Orda’s appeal to the Japanese government in January 1919, ‘for Alash Orda, mobilizing 150,000–200,000 warriors posed no particular difficulty—the real problem was the lack of weapons and ammunition’. The Czechoslovak Corps was the first entity to whom Alash Orda turned for military support. It was not Russia’s anti-Bolshevik forces but the Corps’ uprising in May 1918—which drove Soviet power out of the Far East, the Urals, the Volga region, Siberia, and the northern areas of the Alash autonomy—that enabled the Alash Orda Council to begin functioning as the government of a de facto sovereign state in June 1918 and to form the first anti-Soviet administrations. The revolt itself had been triggered by the Soviet authorities’ attempt to disarm and disband the Corps.

The Czechoslovak Corps had been formed within the army of the Russian Empire in the fall of 1917 from units composed of Czech and Slovak volunteers, prisoners of war, and defectors from the Austro-Hungarian and German armies who wished to continue fighting against their former states. From 16 to 20 May 1918, a congress of Czechoslovak military personnel was held in Chelyabinsk, during which the Temporary Executive Committee of the Czechoslovak Army Congress was established. At this congress, Captain Khamit Toktamyshev, commander of the 1st Cavalry Regiment of the Alash army and future head of the Alash Orda Military Council, delivered a welcoming speech on behalf of the Alash Orda Council.

Czechoslovak Corps, 6th Rifle “Hanácky” Regiment. 1917 / Wikimedia Commons

This demonstrates that Alash Orda was cooperating with the Czechoslovak Corps even before Marsekov visited the Czechoslovak consul in Vladivostok. By the summer of 1918, the Czechoslovak Corps was the only combat-capable force in post-imperial Russia, numbering up to 50,000 troops, while the Red and White armies were just beginning to form and lacked real fighting capability.

However, in January 1919, when Raimjan Marsekov was discussing military-political assistance with the Czechoslovak consul, the commander-in-chief of the Czechoslovak Corps was General Maurice Janin of France. By December of that same year, the first ships carrying Czechoslovak soldiers had already departed Vladivostok for Europe, and their weaponry did not go to the Alash Orda Council or its emerging Kazakh army, but was most likely transferred to the forces of the White movement.

Alash and the West: The Hopes and Calculations of the Great Powers

The negotiations with the Czechoslovak consul were not Alash Orda’s first contact with representatives of foreign states. According to Alikhan Bukeikhan’s statement to an NKVD investigator, in the spring of 1918, he sent Alash Orda envoys Akhmet Baitursynuly, Mirjaqyp Dulatuly, and Raimjan Marsekov to Eastern Turkestani

While reporting this to the Russian envoy in Beijing in a telegram, Dolbezhev asked him to provide a telegraphic directive regarding Alash Orda’s request. To obtain the desired directive from Beijing, the tsarist consul assured the envoy that the Alash Orda Council ‘could deploy 40,000 Kazakhs for joint action against the Bolsheviks’. Yet these contacts, likewise, failed to produce the expected results.

Delegation of the Alash Orda National Council headed by Akhmet Baitursynov, sent to China by Alash Orda chairman A. N. Bukeikhan in March 1918. Chuguchak, March 1918 / Courtesy of Sultan Khan Akkuly

Details of the negotiations between Alash Orda and General William Graves, the commander of the American Expeditionary Corps in the Russian Far East, as well as with Roland Morris, the US Ambassador to Japan, became known from Raimjan Marsekov’s testimony to an NKVD investigator in April 1938.

The United States had an extraordinary and plenipotentiary ambassador in the Russian Empire, as well as consuls in Vladivostok, Omsk, Irkutsk, and other big cities. Yet, Marsekov specifically chose to negotiate with the US ambassador in Japan. Moreover, he met the American diplomat precisely at the moment the ambassador arrived in Vladivostok aboard a battleship. Therefore, the meeting with Morris in Vladivostok was not coincidental: either the negotiations had been arranged in advance, or Marsekov had been informed about the ambassador’s visit to Japan.

In December 1917, after the Bolsheviks established rule, Russia effectively exited the First World War. The Bolsheviks proposed peace without annexations or reparations, but Russia’s Entente alliesi

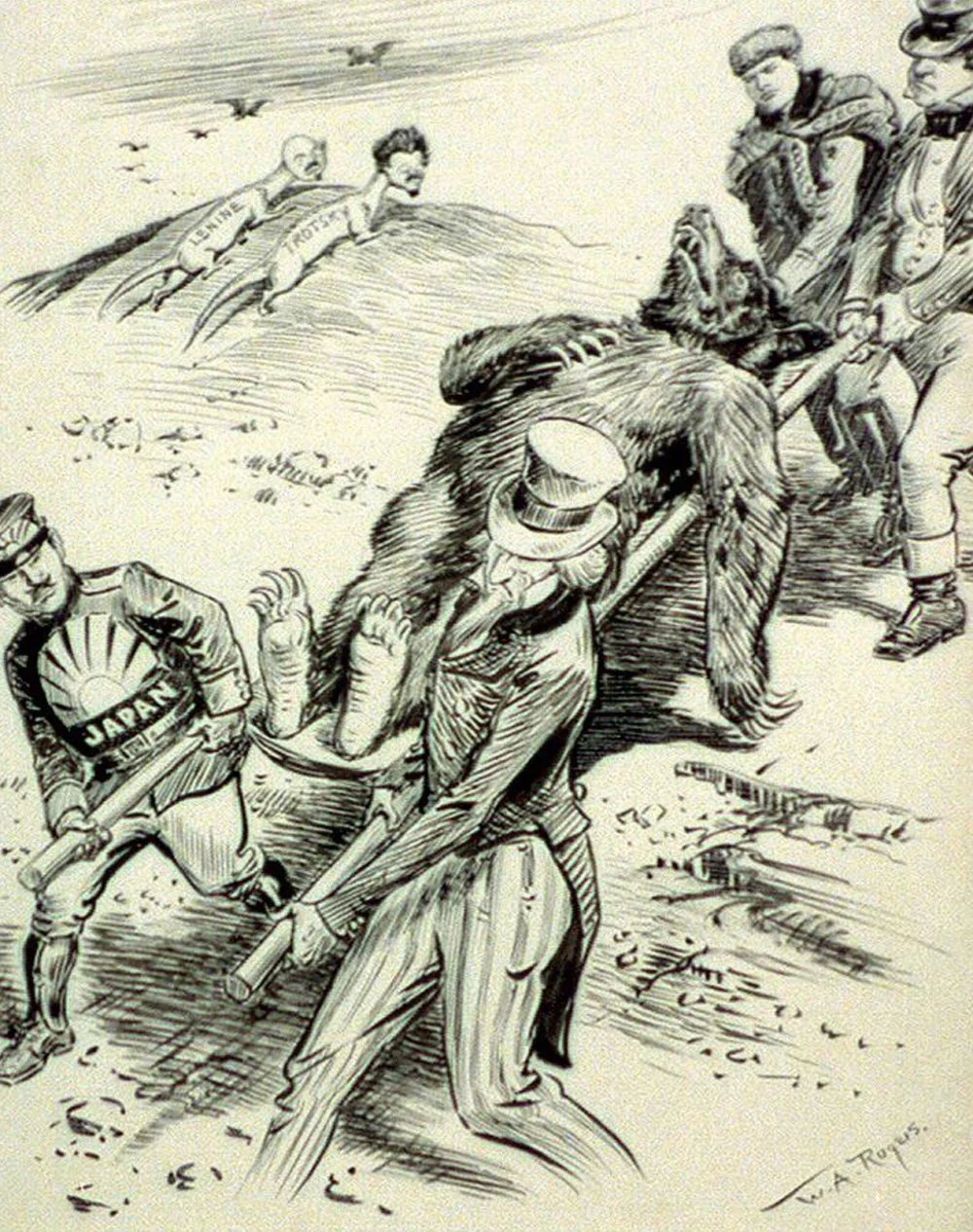

Caricature depicting the wounded “Russian Bear” carried on a stretcher by the Allies, with “lizards” Lenin and Trotsky, leaders of the Bolsheviks. 1918 / Getty Images

Indeed, the leaders in England, France, and Italy believed that power in Russia had fallen into the hands of a pro-German party that was negotiating with Germany for a separate peace and the country’s exit from the war. For this reason, the Entente bloc decided to support those forces in Russia that did not recognize the treacherous and illegitimate rule of the Bolsheviks.

On 22 December 1917 in Paris, the Entente powers recognized the importance of maintaining relations with the anti-Soviet governments of Ukraine, the Cossack regions, and Siberia, including the Alash Republic. According to an agreement signed between England and France on 23 December 1917, which defined each country’s sphere of responsibility in the former Russian Empire, England took responsibility for the Caucasus and the Cossack regions, France for Bessarabia and Ukraine, and the United States and Japan for Siberia and the Alash autonomy.

Thus, the intervention of Russia’s former Entente allies corresponded, to some extent, with the interests of Alash Orda.

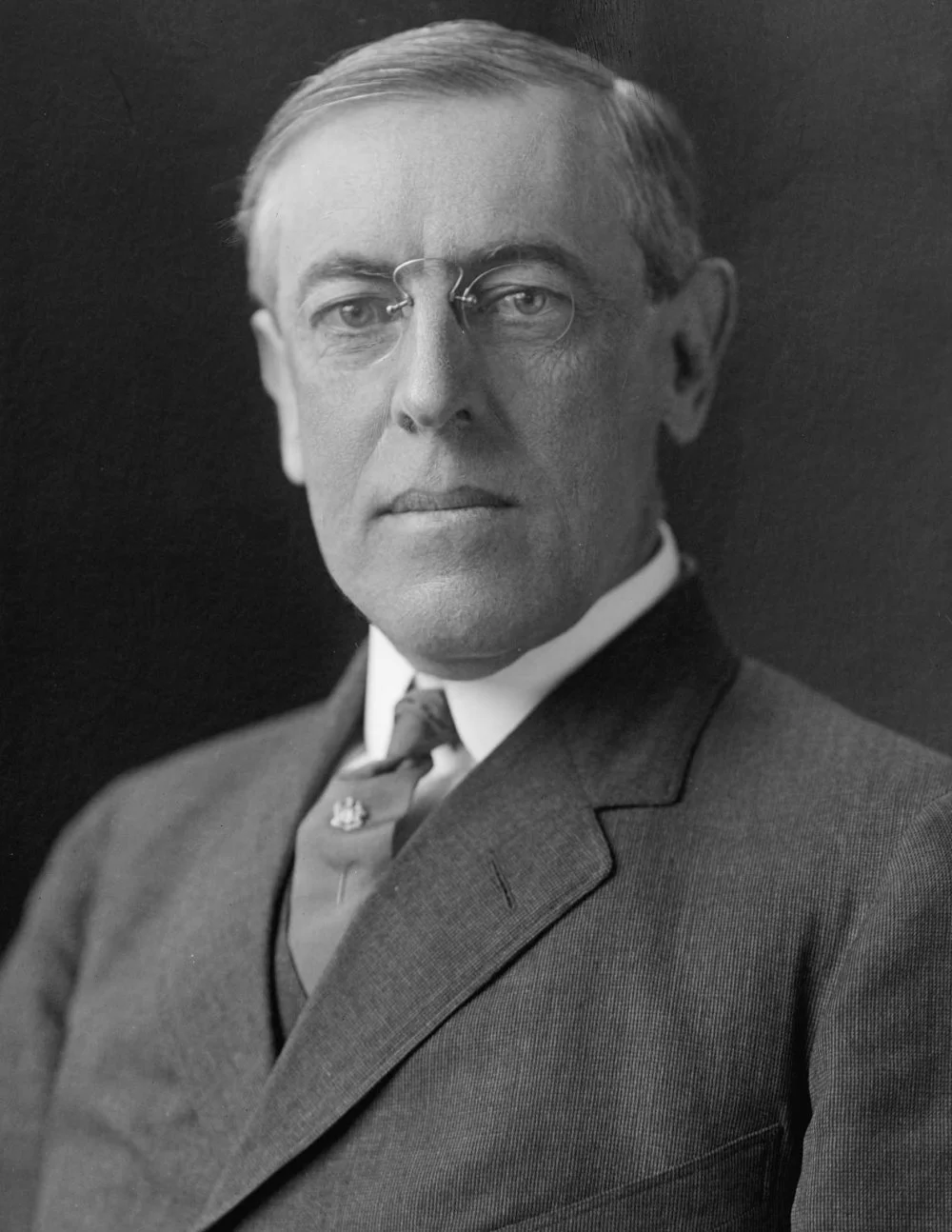

Wilson and the East: Diplomacy of the Fourteen Points

The US president Woodrow Wilson viewed Admiral Kolchak’s rule as a reactionary military dictatorship that should be replaced by a democratic civil government—which is precisely what the leaders of Alash sought. Wilson’s position became decisive in the preparation of the note from the Allies—England, France, Japan, and the US—to Admiral Kolchak on 26 May 1919. Instead of granting diplomatic recognition to his authority as the ‘Supreme Ruler of Russia’ or to his government, the United States presented Kolchak with a list of conditions that determined whether American assistance would continue. These included convening the Constituent Assembly, which the Bolsheviks dispersed in January 1918, expanding local self-government, and guaranteeing civil liberties.

In addition, in January 1918, Wilson proposed a fourteen-point peace plan to end World War I. The document called for disarmament and the granting of broad autonomy to former colonies. The fourteenth (and last) point of Wilson’s peace plan, which spoke of ‘guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity for large and small states’, was completely aligned with the interests of the Alash Orda Council. There is no doubt that the central goal of Marsekov’s negotiations—first with General Graves and then with Ambassador Morris—was to secure recognition and support for the political independence and territorial integrity of both large and small states, including newly formed national entities such as the Alash Republic, Bashkortostan, and Turkestan, all of whose shared interests abroad were represented by Bukeikhan.

Woodrow Wilson Portrait. 1912/Wikimedia Commons

It is evident that one of the key issues Marsekov discussed with the commander of the American Expeditionary Corps in Siberia was the provision of military and technical support to the Alash Orda government in its struggle against Bolshevik rule. As stated in the Alash Orda letter to the government of Japan, delivered by Marsekov to the Japanese diplomatic mission in Vladivostok on 17 January 1919, by mobilizing 40,000–50,000 armed fighters, Alash Orda, together with Turkestan and Bashkortostan, could have expelled the Bolsheviks’ occupying Red Army from their territories. However, General William Graves noted in his memoirs that on 3 August 1918, he received orders explicitly stating that no US representative was to intervene in Russian internal affairs or take sides.

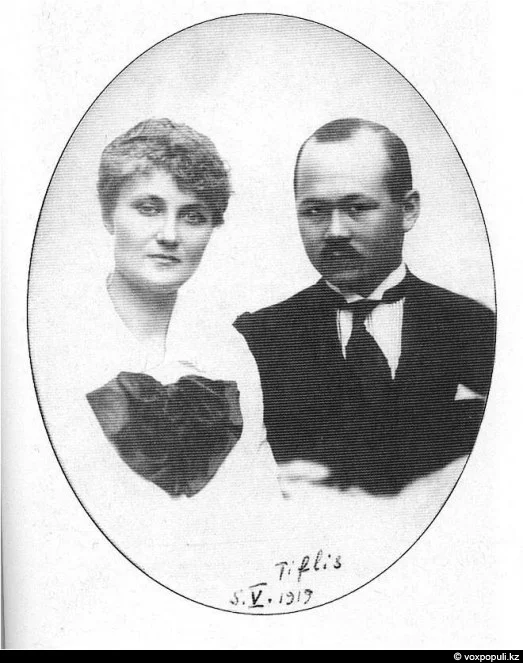

At the same time, Mustafa Shoqay, the well-known Kazakh social and political activist, was delegated by Alash Orda Council chairman Alikhan Bukeikhan to the Paris Peace Conference. He was delayed in Tiflisi

Mustafa Shokay with his wife Maria in Tiflis. 1919 / Wikimedia Commons

These facts lead us to an obvious conclusion: the recognition of the Alash Republic’s statehood and independence, establishing diplomatic relations with it, or providing it with military-political support were not part of the White House’s plans. Further, addressing such matters would have been impossible without the approval of the US Congress. The White House considered these actions as interference in Russia’s internal affairs and as taking sides—either with the Bolsheviks or the anti-Bolshevik forces. Overall, each of the Entente allies acted in Russia purely to advance its own interests.

Eastern Focus: The Appeal to Japan

We now have information about Alash Orda’s negotiations with Japanese representatives from the archives of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as well as from the research of the Japanese scholars Ryosuke Ono and Tomohiko Uyama. Based on Marsekov’s appeal to the Japanese government on behalf of Alash Orda, these researchers have suggested that the Alash Orda and the Bashkortostan government intended to establish contact with Japan. At a meeting of leaders from Alash, Bashkortostan, and Tatarstan in Ufa in April 1918, it was decided to send representatives to Kuljai

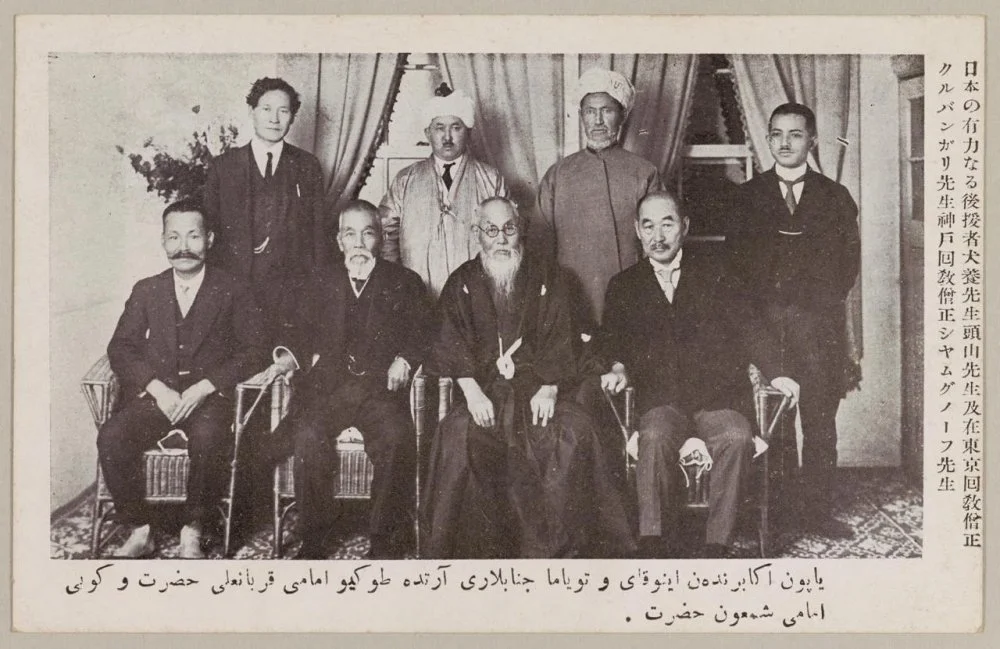

Early 1930s. Leaders of Japanese Nationalists (including future Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai and Mitsuru Tōyama) and émigré Turkic-language communities. Kurbangaliev is second from the left, back row/Wikimedia Commons

During his visit to the Japanese consulate general, Marsekov stated that his goal was to establish political and economic relations with Japan. In a conversation with the head of the mission, who would presumably have been Deputy Consul General Rie Watanabe in Vladivostok, as well as in a written statement prepared at the mission’s request, he explained that ‘the Kazakh people have been under Russian rule for nearly two centuries, yet ongoing oppression compels Alash Orda to appeal to the Japanese government for assistance in securing recognition of the sovereignty and independence not only of the Alash Republic but also of several other Turkic-speaking peoples related to the Kazakhs’.

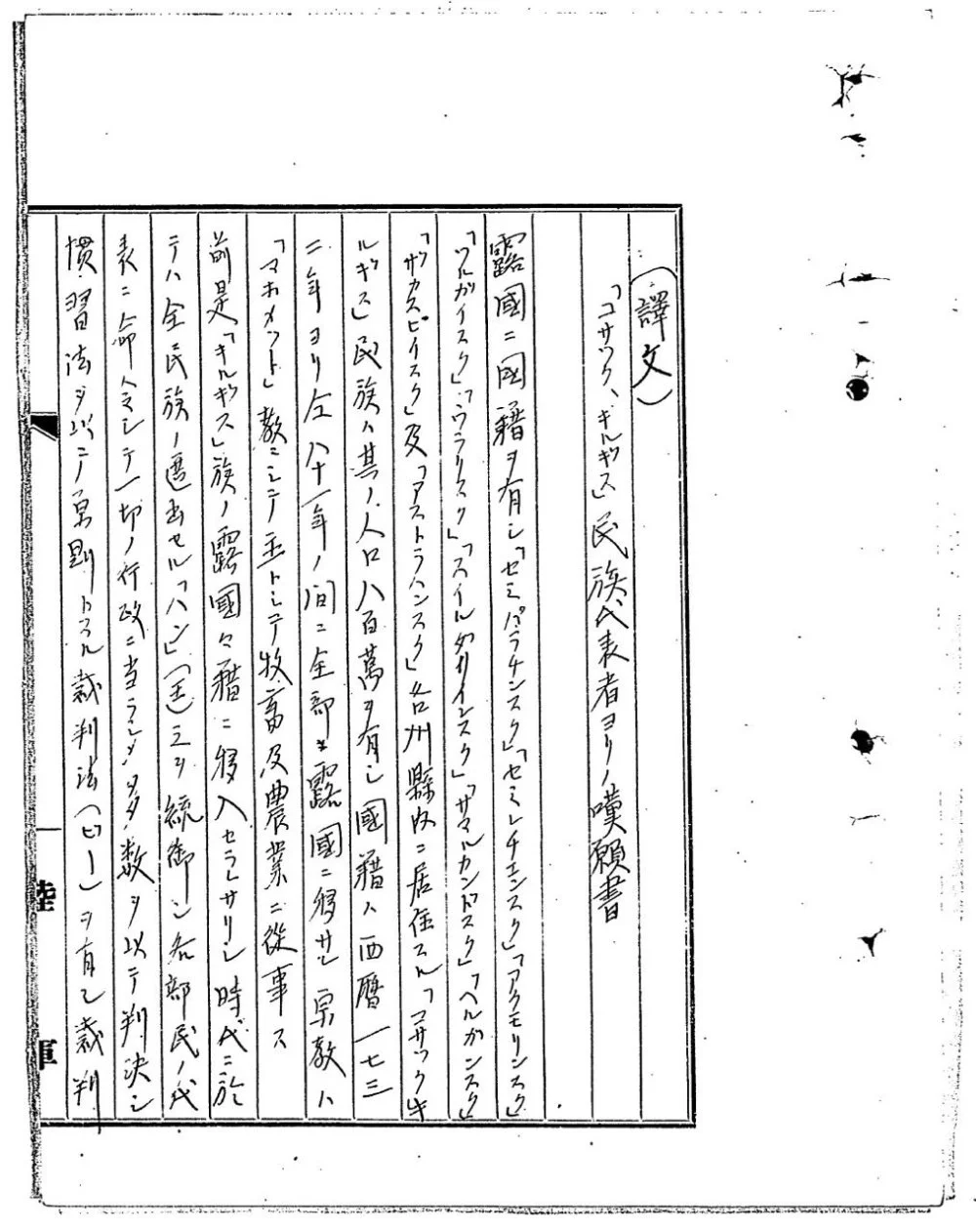

Excerpt from a letter by Raimzhan Marsekov to the Japanese government / Courtesy of Tomohiko Uyama

In his appeal, he also expressed Alash Orda’s interest in receiving financial assistance and military-technical resources for an army numbering 40,000 to 100,000 troops. The document contained an important request for the Japanese government’s assistance in securing recognition of the Alash Republic’s independence at the Paris Peace Conference by the victorious powers of the First World War and to allow an authorized representative of Alash Orda to participate in that forum.

As we know, Mustafa Shokay, the authorized representative of Alash Orda at the Paris Peace Conference, was delayed in Tiflis while awaiting confirmation of Japan’s readiness and a French visa. He remained there until the Soviet army invaded Georgia on 16 February 1921 and only reached Paris a year and a half after the Peace Conference had concluded. By that time, all national governments, including Alash, Bashkortostan, and Turkestan, had once again fallen under Soviet occupation.

William Orpen. The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles, 28th June 1919/ Wikimedia Commons

As for Raimjan Marsekov’s visit to the Japanese diplomatic mission in Vladivostok, due to the lack of official authorization from Alash Orda, the Japanese government declined to provide an official response to his appeal, treating him as a private individual rather than a representative of his government. Nevertheless, the mission's head, Rie Watanabe, committed to forwarding the matter to the appropriate authorities.

The Japanese government likely proposed that Alash Orda organize the education of Kazakh students in Japan, Europe, and the United States. The Vol’nyi Gorets newspaper reported that upon learning of Kazakh students being deprived of the opportunity to study in Russia due to the civil war, the Japanese government, through its representatives in Siberia, offered to send these young people to Japan to study. Students were provided with benefits, including free travel, tuition coverage, and full support while attending educational institutions in the Land of the Rising Sun.

The Legacy of Alash Orda: Diplomacy Ahead of Its Time

By the spring of 1920, Bolshevik authority had consolidated its control over the territory of the Alash autonomy. All state institutions created by the Alash Republic were dismantled: the government, regional committees, the national army, the taxation system, and all legislative acts and decrees of Alash Orda were abolished. The administration of the Kazakh region was carried out by the KazRevKom, a governing body of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR)i

Delegation of Turgai Oblast at the 1st Congress of the Kazakh ASSR. Akhmet Baitursynuly (2nd row, 5th from left) and Alikhan Zhangeldin (2nd row, 4th from right). Orenburg, 1920 / CSACPA

On 25 August 1920, by decision of the highest authorities of the RSFSR, the Alash Republic was replaced the Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Kazakh ASSR)i

With the proclamation of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic (Kazakh SSR) and its inclusion in the USSR in 1936 as a union republic, it was asserted that, like other federal subjects, it possessed sovereignty limited by the union constitution. However, these limitations were so comprehensive that real independence was out of the question. With the addition of totalitarian supra-state party control, it becomes clear that the ‘limited sovereignty’ existed only as a decorative slogan, masking the real sovereignty that had been held by the Alash Republic.

The Declaration of Sovereignty of the Kazakh SSR, adopted on 25 October 1990, and celebrated today as Republic Day, essentially marked the restoration of the sovereignty that had been lost seventy years earlier, on 25 August 1920, following Kazakhstan’s occupation by the Bolshevik regime.