Before permanently departing the USSR, Trotsky, one of the prominent leaders of the Russian Revolution, was exiled to Almaty. There, he spent considerable time writing, complaining, hunting, and simultaneously protecting tigers.

‘In Alma-Ata the snow was good, white, clean, dry … In spring, it was replaced by red poppies. There were so many of them—huge carpets, the steppe was covered with them for many kilometers, everything was red. In summer, there were apples, the famous Alma-Ata Aport apples, also big and red … The garden underwent several changes. It was covered with flowers. Then the trees were heavy, with low hanging branches on stakes. Then the fruit lay in colorful carpets under the trees, on the straw bedding, while the trees, freed from their burden, lifted their branches again. The garden smelled of ripe apples and ripe pears, and bees and wasps buzzed about. We made jam.’ This may sound like emigrant prose, but it’s actually an excerpt from the diary of Natalia Sedova, Leon (in Russian, Lev) Trotsky’s wife, describing their life in exile, which began in January 1928 in Almaty.

On 18 January, Leon Trotsky and his family were sent to the Yaroslavsky Train Station in Moscow. GPU agents had to break down the door of the apartment, and three of them had to carry Revolutionary No. 2 (after Lenin) out by force as he refused to move. The agents probably did not have to exert themselves since Trotsky was reported to be short and gaunt. In fact, this was not the first time he’d pulled a trick like this. In March 1917, British sailors had carried him off the Norwegian steamship SS Kristianiafjord.

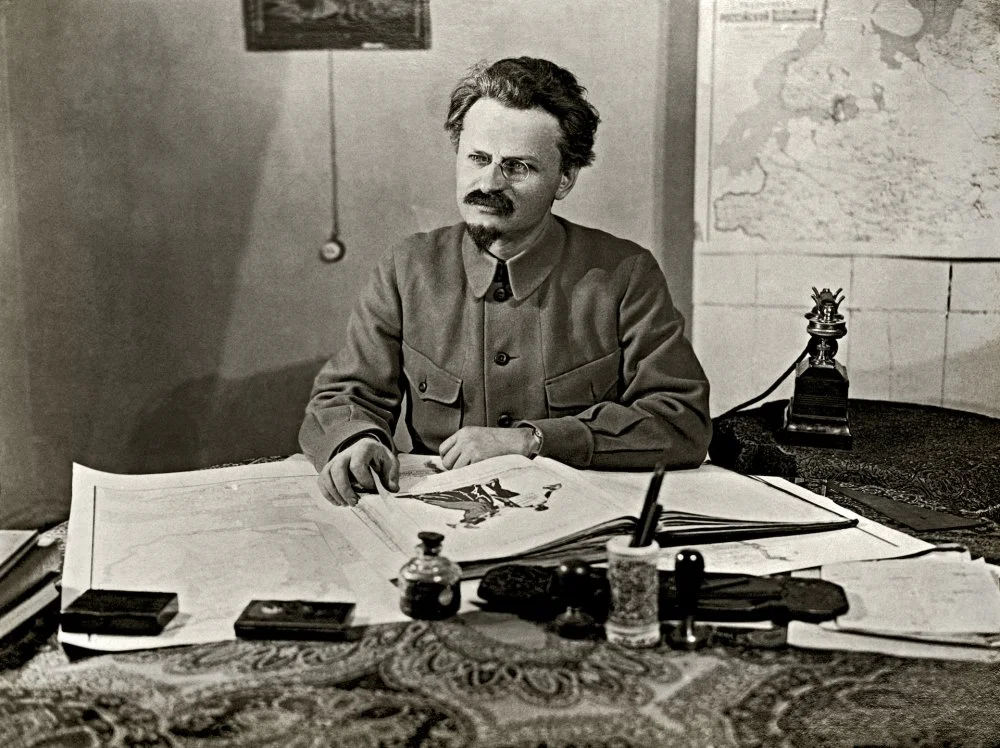

Leon Trotsky/getty images

In Moscow, Trotsky was carried down the stairs while his son shouted, ‘Comrades, see how Comrade Trotsky is being carried!’ This anticipates a scene in The Golden Calf by Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov, published in 1931, where Panikovsky, a petty criminal, is carried out of the Executive Committee building. Trotsky himself, according to his wife’s recollections, was ‘cheerful, almost jovial’ during this operation. The former War Commissar, who had only recently traveled in his own train through the deadliest parts of the front, was pushed into a railroad car and taken to Bishkek (Frunze). From there, he was taken by car through the Kurdai Pass to Almaty, which at that time, was considered quite a distance. There’s a joke in the classic Kazakh film Amangeldy (1939) that goes: if Lenin had hidden from the tsar in Kazakhstan, no one would have found him here. The acting chairman of the Soviet Revolutionary Military Council, Voroshilov, also quipped after Trotsky’s expulsion: ‘If he dies there, we won’t know for a long time.’

Trotsky himself later admitted in his memoirs that from that time on, the main puzzle of his life was ‘the answer to the question that so many people asked: how did you lose your power?’

In fact, it is still difficult to understand how this high-ranking, powerful official in a red-lined coat, with cities and destroyers named after him, who could quickly sway a crowd of Kronstadt sailors, whose birthday was 7 November, the day of the Revolution, lost the political struggle (and later his life) to Joseph Stalin, then a relatively negligible figure, in the country Trotsky himself had created.

The first conflict between Stalin and Trotsky dates back to 1918, when they disagreed on the expediency of using military specialists in the Red Army. Ten years later, the man of position would finally prove his superiority over the man of ideas. A massive campaign against Trotsky began in 1923, and his withdrawal, in fact, was somehow foreshadowed in 1924, when Trotsky missed Lenin’s funeral because he was stuck in Sukhumi for medical treatment. There’s no clear explanation as to whether he actually couldn’t get to the funeral in time or whether Stalin deliberately misinformed him about the date. In any case, his failure to appear in Red Square on 27 January did not help his cause.

When Trotsky began to speak out against the party apparatus and what he called bureaucratic absolutism, he was already playing a game imposed on him by his rival general secretary. However, in this game, he could only be a hero, not a winner. Trotsky dreamed of revolution on a global scale and was generally a figure of great importance. However, in the new local and practical context, he was somehow out of the picture. In the course of the Civil War, Trotsky could order the execution of every tenth soldier (as at Sviyazhsk) and was rightly known as a theorist (and practitioner) of ruthless struggle, but in peacetime, his evil genius lost out to brutal mediocrity.

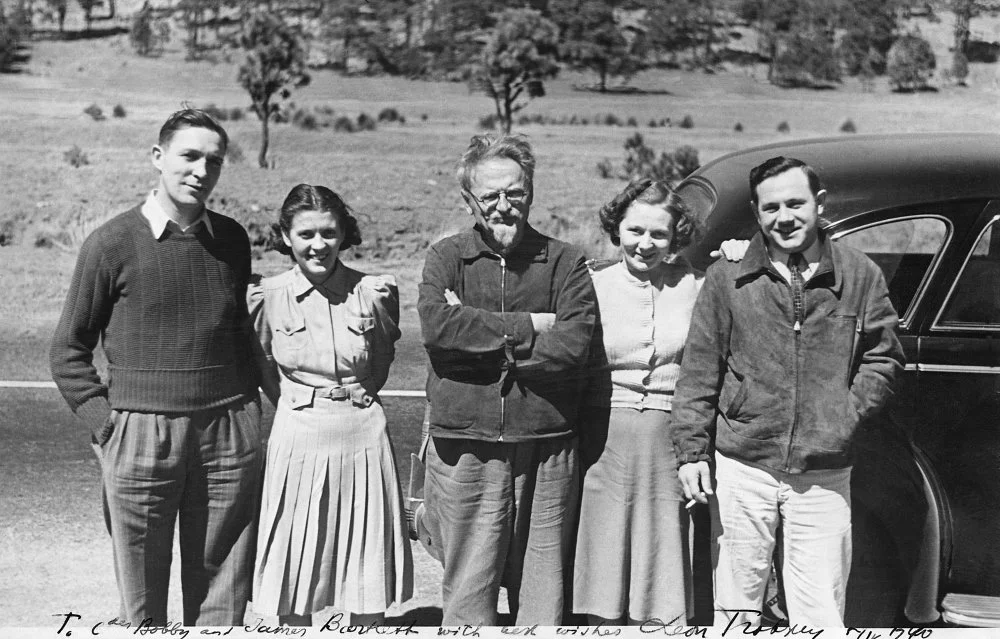

Leon Trotsky, founder and first leader of the Red Army, with friends in Mexico /Getty Images

It is interesting to listen to Trotsky’s voice in recordings from the 1920s. It sounds hypnotic and still imperious, but it is already the voice of an outsider. He has the arrogant tone of a poet who is not afraid to stand alone, as he put it, ‘in anticipation of the future majority’. Upon his arrival in Almaty, Trotsky was faced with the same problem as Russian emigrants in the fall of 2022—there was no place to live. In any case, all the apartments he could theoretically claim due to his rank had been occupied by the Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) party leadership, who had moved here from Kyzylorda.

His first shelter was the Hotel Jetysu on Gogol Street, where, as his wife aptly put it, the former People’s Commissar was welcomed with ‘rooms furnished from Gogol’s time, indeed’. For the first few days, he did not leave his room.

Later he was transferred to a villa on Krasin Street with a car, servants and omnipresent guards. Trotsky did not like the ‘climate situation’, but he appreciated the electricity in the house. In general, Trotsky complained a lot and eagerly in the new place. He was dissatisfied with ‘restaurant food, ruinous to health’, the weather, the lack of sidewalks, dirt, malaria (‘malaria works, but bread does not!’), leprosy, rabid dogs, fleas, and what he called ‘prison conditions of existence’. The pinnacle is his autumn letter to Moscow asking that they send him overshoes that were not available here in size 11 or 11.5. They were delivered—of the famous Red Triangle (Красный Треугольник) brand.

His lordly ways were well known in the Soviet era—whether it was his cars, his entourage, or his way of ostentatiously reading French novels at party meetings. Part of the reason for his whimsical behavior was that Trotsky valued discipline and system over adventure and chaos (remember, he took his pseudonym from the surname of a prison guard).

As a result, by summer he had secured a dacha (an izba, a Russian country house, as his wife called it) in the foothills, now the site of the National Library. In general, he was not so wrong about the conditions of his imprisonment, for during the tsarist repressions he, like other exiles, was allowed to hunt and thus had easy access to firearms.

Strictly speaking, it was hunting that ruined him. It was while killing other animals in October 1923 that Trotsky caught a cold and developed what he called ‘a cryptogenic fever’. Because of this illness, he missed the very beginning of the anti-Trotskyist campaign and Lenin’s funeral. As he rightly noted in his memoirs, ‘one can foresee revolution and war, but one cannot foresee the consequences of an autumn duck hunt’.

Interestingly, while in Almaty, Trotsky had time to sign a pact to protect the unique Turanian (Caspian) tiger. He probably felt he was himself on the verge of extinction. Despite his efforts, this tiger was extinct in Kazakhstan by 1948—and Trotsky was killed eight years earlier.

Exiled communist Leon Trotsky dies in a hospital after being fatally wounded by a Stalinist agent. /Getty Images

Nevertheless, the Soviet authorities did not immediately succeed in expelling him from big politics as they had once done at the Yaroslavsky Railway Station. In Almaty, he worked actively, tried to form a congress of like-minded people, and wrote so much that the old party nickname ‘the Pen’ took on a new meaning (though he was also assigned a typist). Here, he wrote: ‘To refute a dozen slanderous statements by Carl Vogt, Marx wrote a book of two hundred pages in very small type … What if we were to refute the slanders of the Stalinists on the same scale? We would have to publish perhaps a thousand-volume encyclopedia…’

There would be no thousand-volume encyclopedia, but from April to October 1928, Trotsky sent 800 long letters from Almaty, some containing major theoretical works, and more than 500 telegrams.

Here, he met people from his old life—for example, a man with the Dostoevskian surname Vladimir Shatov, the head of the Turksib Railway, who in October 1917 was a member of the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee. He also began to write such seminal works as The Permanent Revolution, The History of the Russian Revolution, and others during this time. Photographs of his walks have not survived, but it is easy to imagine surreal images of the exile in the state of his own invention—Trotsky under the monument to Dzerzhinsky, Trotsky in the party club named after him in Federation Park. In Semirechye, at the time of his exile, there was already a town named after him. Not surprisingly, the workers of Almaty sometimes perceived him as a government inspector on a secret mission (not for nothing did he settle on Gogol Street, named after the author of the famous play The Government Inspector).

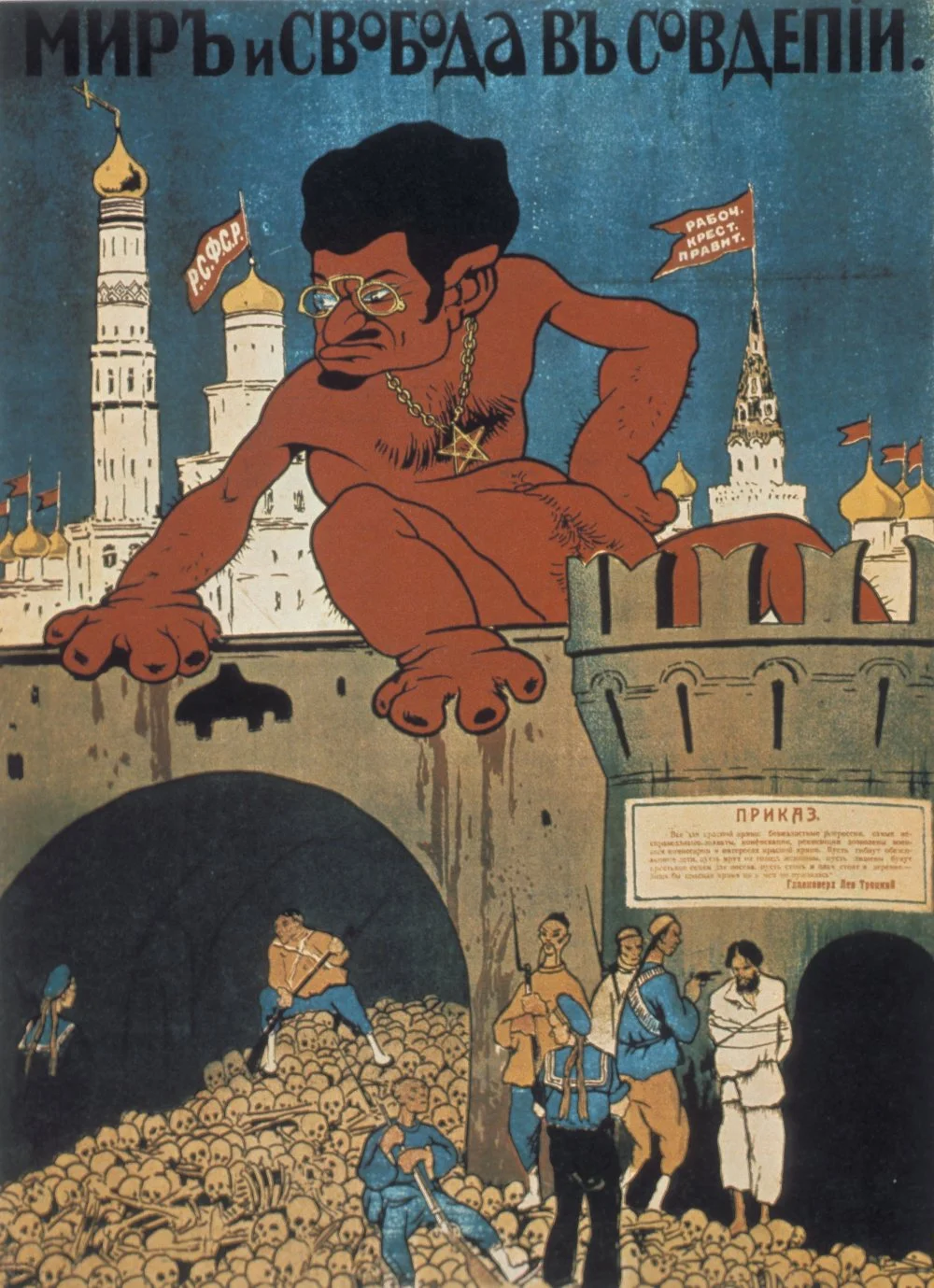

USSR White Army propaganda poster depicting a demonic Leon Trotsky/Getty Images

At the same time, Trotsky prepared for a retreat (or rather an offensive, given his temperament) to the West, but the European countries denied him entry as he was dangerous and under sanctions in both Russia and Europe. Stalin, through the GPU, offered him the chance to renounce political activity, which was exactly the same condition imposed by the German government. Trotsky found himself in an airless space that he called ‘a planet without a visa’. His comments on embassy bureaucracy constitute a genre of their own: ‘This text of renunciation could have been written by Bernard Shaw!’ or ‘The USA is not only the strongest, but also the most frightened country!’ Even today, his denouncement of the hypocrisy of European democracy seems familiar: ‘The variety of reasons for which democratic countries deny visas is very wide. The Norwegian government, as you can see, bases its decision solely on considerations of my safety. As you know, the right to asylum is a sacred and inviolable principle. But an exile must first provide Oslo with a certificate that he will not be killed by anyone … The French government was much wittier: it simply pointed out that Malvy’s order to expel me from France had not been revoked. A totally insurmountable obstacle to democracy. Where is the country in which this right has found its refuge? Could it be England? … I was flatly refused a visa. Clynes, the minister of police, defended the refusal in the House of Commons. He explained the philosophical nature of democracy with a directness that would have honored any minister of Charles II. The right of asylum, Clynes said, does not consist in the right of the exile to claim asylum, but in the right of the state to deny it.’

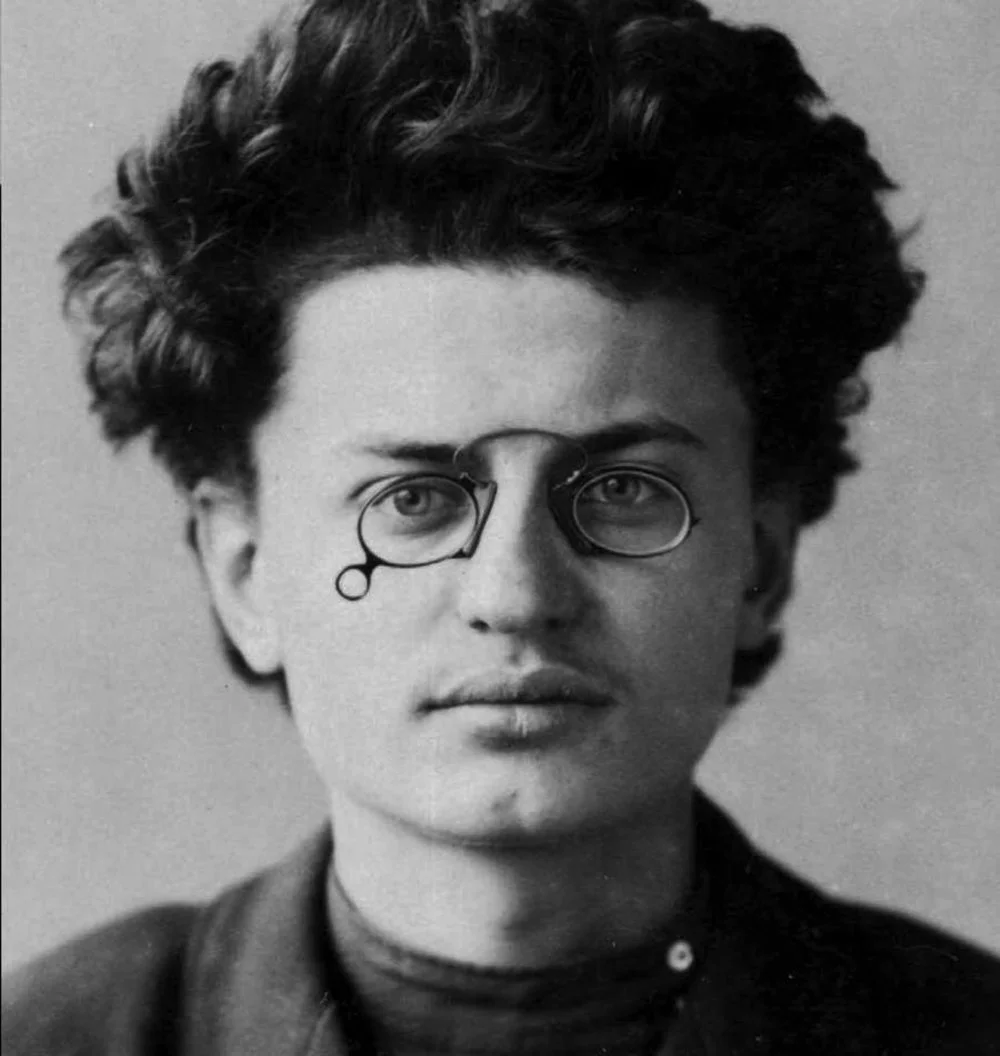

Leon Trotsky/Getty images

On 9 June 1928, his twenty-six-year-old daughter and fellow activist, Nina, died of tuberculosis in Moscow, shortly after being expelled from the party following her father. Trotsky was denied permission to attend the funeral. This was the first, but not the last, shock he received of this kind—he would outlive all four of his children.

In November 1928, his correspondence with the outside world was finally curtailed. In December, an order to that effect arrived in Almaty, and in January 1929 Trotsky was expelled from the USSR for organizing an anti-Soviet party and preparing for armed struggle. Trotsky was taken out on the same route he was brought in—through the Kurdai Pass to Frunze, then to his native Odessa, from there to Constantinople (Istanbul) on an empty steamer Ilyich (he should have been on the steamer Kalinin, but it was frozen). The Soviet government paid him $1,500 as indemnity. Although he did not meet Diego Rivera or Frida Kahlo in Almaty, as he did in his next destinations, and the city in general did not excite him much, it can be assumed, in retrospect, that Almaty was the last comparatively peaceful milestone in his forced wanderings.

Lev Trotsky with his wife and Frida Kahlo in Mexico. 1937/Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans/TASS

At least here he was comparatively safe, unlike Constantinople, which was overcrowded with White Guard refugees, nearly all of whom had some grievance with the newly arrived Red Army chief.

In one of the best novels about the Russian Civil War, The Beast from the Abyss (1923) by the Russian émigré writer Yevgeny Chirikov, there is an episode that quite eloquently describes the attitude toward Trotsky among, for example, the former Kornilov soldiers:

‘He drew a human-sized figure, put it against the rocks and fired. A girl asked about the figure: “Daddy? Is that Uncle?”

“Yes, yes. Uncle Trotsky.”

He riddled Uncle Trotsky with bullets and happily rubbed his hands together.’

Once in Turkey, Trotsky wrote: ‘Here I am in a bivouac.’ He still had eleven years to live. But after shooting pheasants and quail in Almaty, he immediately became the target of the hunting season himself. It is probably no coincidence that his Kazakh idyll evokes a parallel with his first, albeit not entirely reliable, memory of existence: ‘I had a vague recollection of a scene under an apple tree in the garden, which happened when I was about a year and a half old.’ At the very least, the exile of 1928 allowed him to do what he loved to do—spend time anticipating the future of the majority.

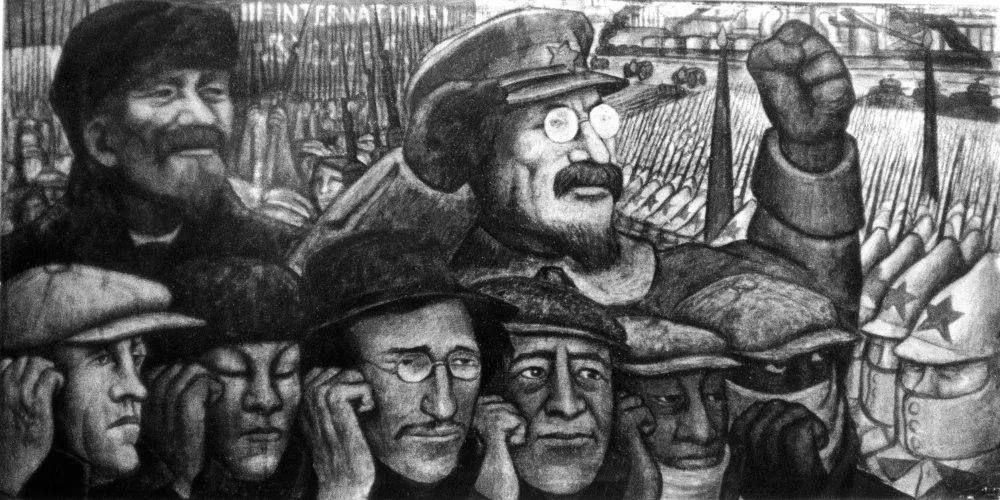

Diego Rivera. 3rd International. Lenin and Léon Trotsky among representatives of different countries, Mexico,, Mexico. Museum of Fine Arts,, 1920-1943/Getty Images