In May 2025, at an event hosted by the Qalam Club, Kishore Mahbubani—widely regarded as one of Asia’s most influential intellectuals, a former diplomat with three decades of experience, the ex-president of the UN Security Council, and the author of several global bestsellers—offered a compelling insight: Asia is reclaiming its historical role as a global leader. And the world, increasingly interdependent and interconnected, must reckon with this transformation.

The End of an Aberration

We are living through one of the most amazing moments of world history. The era of Western dominance is drawing to a close. This does not mean the end of the West itself—it will remain the world’s most powerful civilization for years to come. But its ability to unilaterally steer global affairs, as it has done for the past two centuries, is disappearing.

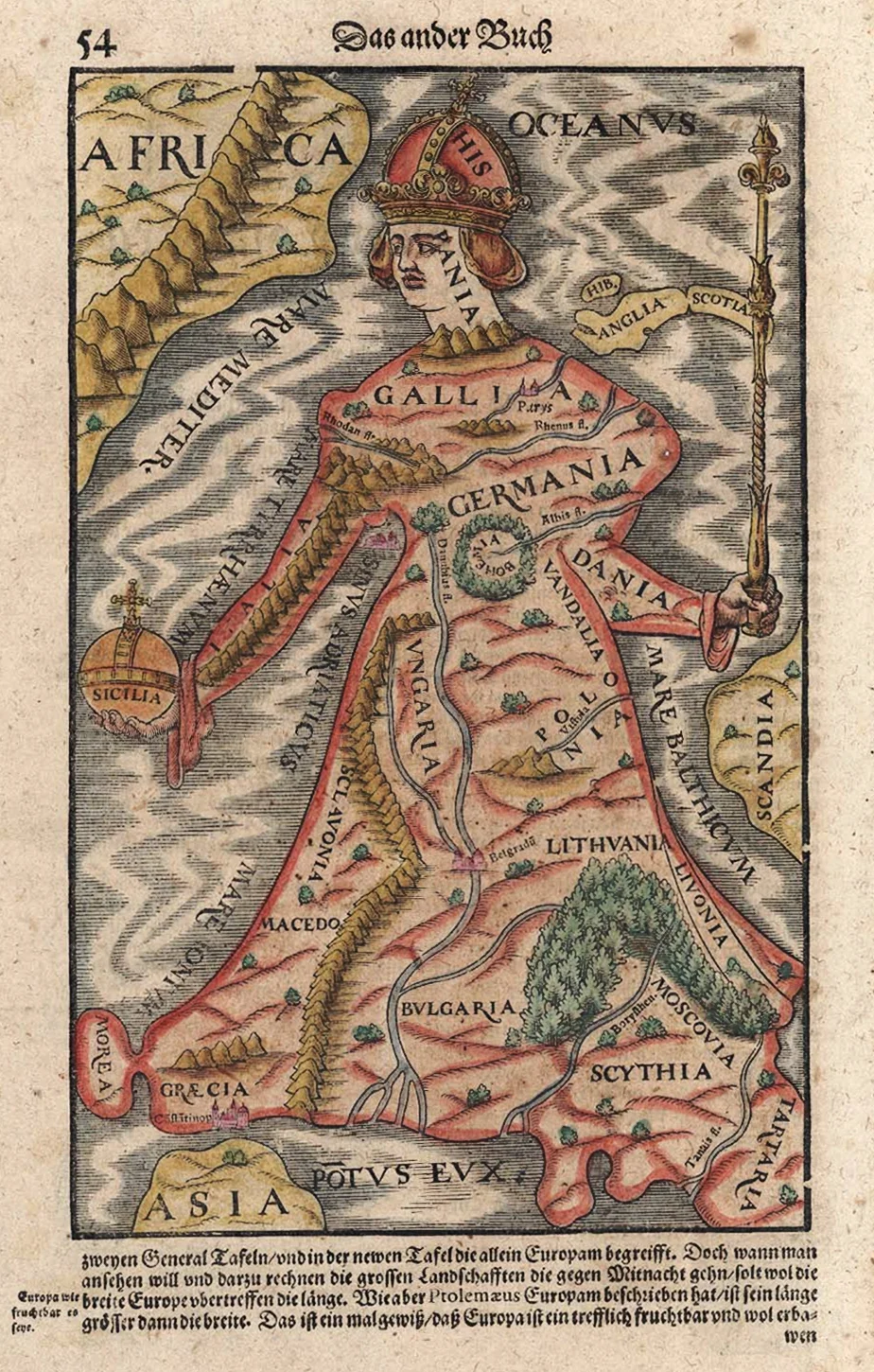

Sebastian Munster. Map of Europe as a Queen. 1570 / Wikimedia Commons

In my recently published memoirs, I reflect on what it was like to grow up in a British colony. I was born in 1948, and as an Asian child, I felt intellectually and culturally inferior to the West. The mental colonization of Asia was profound—it helps explain how, a century ago, 100,000 Britons were able to rule over 300 million Indians. That world is now vanishing. In its place, we are witnessing the historic return of Asia—a shift that is set to reshape the global order.

The ‘Shrinking’ of the World

This return to prominence is unfolding alongside another profound transformation: the ‘shrinking’ of the world. A simple metaphor illustrates the point. Previously, eight billion people lived in 193 separate countries, much like passengers in 193 separate boats. They might occasionally collide, but they remained largely separate. Today, we all inhabit a single, interconnected vessel with 193 cabins. If a virus breaks out in one, we are all affected.

Herman Heijenbrock. The casting of iron in blocks. Circa 1890s.The Industrial Revolution led to the mechanization of traditional crafts and culture, the equalization of technologies, and economic changes in many countries. It also was one cause of nglobalisation / Wikimedia Commons

The world has grown smaller, but no one is steering the ship. There are only captains of individual cabins. Just as the need for coordinated global governance becomes critical, we see growing disarray. That is the real danger.

The Asian Century Is Here

Despite these challenges, the Asian century is no longer a distant possibility—it is already a reality. Consider these three compelling indicators:

1. In 1980, the European Union’s economy was ten times the size of China’s. Today, they are roughly equal. By 2050, China’s economy is projected to be twice as large as the EU’s.

2. ASEAN’s collective GDP now stands at $3.5 trillion—compared to the EU’s $17 trillion—and yet, between 2010 and 2020, ASEAN countries contributed more to global growth than Europe.

3. In 2000, India was not even among the world’s ten largest economies. Today, it is in the top five. By 2030, it is expected to reach the top three.

why is this happening?

So what explains this resurgence? First, it is a return to historical normality. For 1,800 of the past 2,000 years, China and India were the world’s largest economies. The last two centuries are an exception, not the rule. Second, Asia has learned from the West.

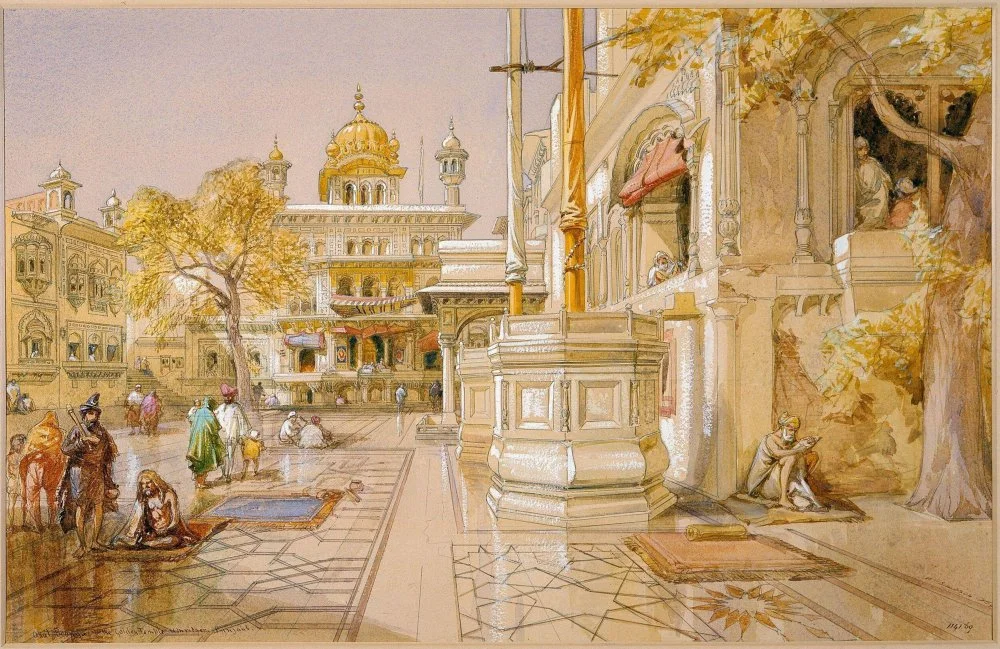

William Simpson. Akal Bunga (Akal Takht) golden Temple. Amritsar, India, 1864 / Alamy

It has absorbed the scientific and technological foundations of Western success. China, for instance, now leads the world in top-tier scientific publications, well ahead of the United States.

Third, Asia has embraced open markets. Ironically, the United States can now no longer sign major free trade agreements. Meanwhile, across Asia countries are forming the largest trade pacts in history.

Challenges to Asia’s Rise

Still, the path ahead is far from smooth. The Asian century will be tested by several challenges, including:

1. Geopolitical Rivalry between the US and China

These are two unprecedentedly powerful states. According to the logic of geopolitics, the established power always seeks to contain the rising one.

2. The Emotional Factor

While not always rational, emotions play a potent role in international relations. Take the Chinese Exclusion Act of the 1890s, for example, which was an early sign of Western anxiety over Asia’s rise. The fear that drove such policies still lingers, feeding tensions even today.

3. Ideology

American leaders often frame the rivalry between the US and China as a contest between democracy and authoritarianism. But even if China were to adopt liberal democracy tomorrow, the strategic rivalry would persist. This is not about ideology—it is about primacy.

Relations between China and India add another layer of risk. Today, those ties are not merely tense—they are openly hostile, and that bodes poorly for regional cohesion.

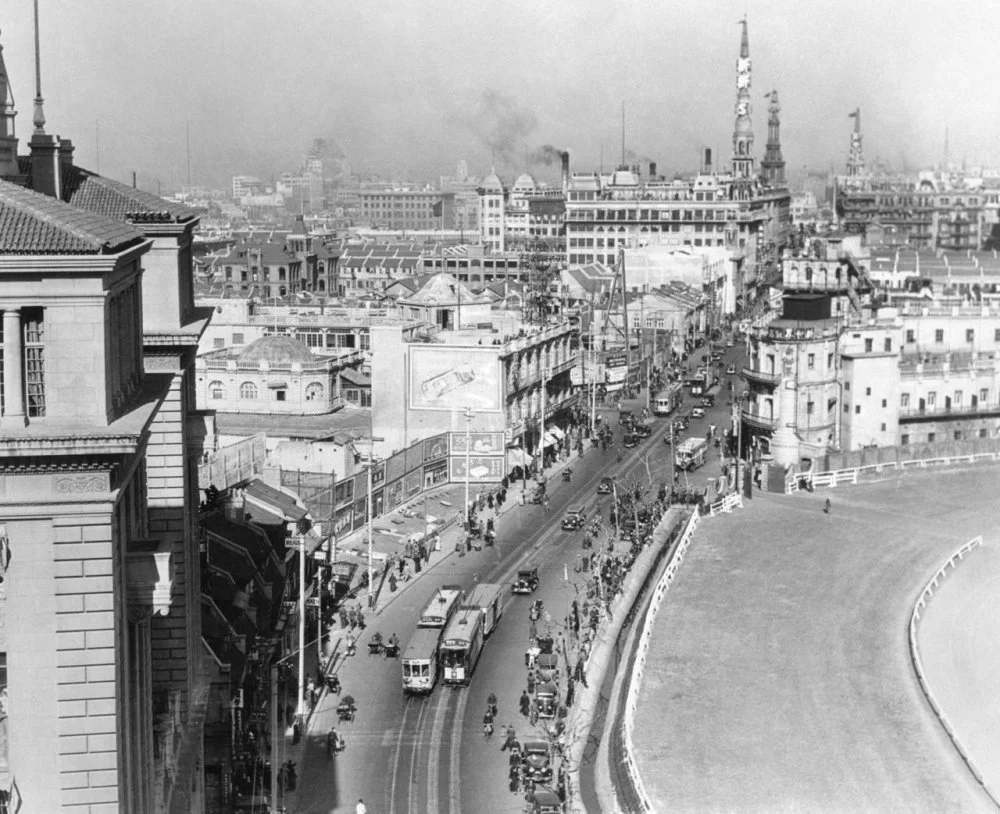

View of Shanghai. 1937 / Getty Images

Compounding these challenges is the weakening of global institutions. Asia’s economic rise was underpinned by international trade rules. Those frameworks are now eroding, creating new uncertainties.

A Eurasian Opportunity

Yet, alongside the risks lie extraordinary opportunities, especially for Eurasia. If the region acts wisely, it could benefit immensely from the shifting global landscape in the following ways:

1. Trade and Tourism

As China, India, and the ASEAN countries expand, Eurasia will become a key artery for commerce and travel.

2. A Booming Middle Class

In the year 2000, China, India and ASEAN had just 150 million people with middle-class incomes. By 2020, that number reached 1.5 billion. By 2030, it could hit 3 billion, signaling the largest socioeconomic shift in human history.

3. The ASEAN Model

The European Union is no longer the standard. Even Henry Kissinger, in our final meeting in 2022, voiced deep pessimism about Europe’s strategic coherence. ASEAN, by contrast, has maintained peace and stability for nearly fifty years through pragmatic, flexible cooperation.

4. Eurasia’s Historic Role Reborn

When China and India dominated the global economy, Eurasia was the corridor through which trade flowed, and that pattern may return. History is circling back, and Eurasia could once again become the world’s commercial crossroads.

Abraham Cresques. Marco Polo’s journey to the East along the Silk Road. Catalan Atlas, circa 1375 / Alamy

The world is entering a new epoch. Asia is not merely rising—it is returning. This is not just a regional realignment—it is a civilizational shift. Eurasia, if it responds with foresight and pragmatism, may find itself at the centre of it. The window of opportunity is rare. But it is currently open.