Canadian historian Ju Yup Lee is trying to answer the questions of how, when and why our people began to be called "Cossacks", what it meant and who Genghis Khan is.

In this essay, I will address three important topics in Kazakh history: 1) Who were the proto-Kazakhs?; 2) Why does qazaqlïq matter?;i

N.K. Roerich. Voice of Mongolia. 1937 / Alamy

Who Were the Proto-Kazakhs?

Who were the proto-Kazakhs or the ancient Kazakhs who developed into the nomadic people that self-identified as ‘Qazaq’? Soviet historians who emphasized the ‘autochthonous’ development of central Asian nationalities argued that the proto-Kazakhs were an amalgamation of all the nomadic peoples such as the Saka (Scythians), Wusun, Xiongnu, Türks, and Qipchaqs who inhabited the steppes of Kazakhstan since the Bronze Age. However, the primary sources produced in central Asia tell us a different story. Specifically, the proto-Kazakhs who resided in the Kazakh steppe prior to the formation of the Kazakhs at the turn of the sixteenth century CE were identified in the primary sources as Uzbek. Who were the Uzbeks? They were none other than the Jochid ulus (people), who began to be called Uzbek after the reign of Uzbek Khan (reigned 1313–41), the Chinggisid ruler who made Islam the state religion of the ulus of Jochi (also known as the Golden Horde). Notably, Timurid historians referred to the Jochid ulus of the Kazakh steppe (and the Black Sea and Caspian steppes), that is, the proto-Kazakhs, as Uzbek. For instance, Niẓām al-Dīn Shāmī, the court historian of Temür (Tamerlane), refers to the realm of Urus Khan (reigned circa 1368–78), great-grandfather of the Kazakh khans Jānībeg Khan and Girāy Khan, as ‘the Uzbeki

During the post-Mongol period, the ethnonym Uzbek, which is usually associated in modern scholarly literature with the ulus of Abū al-Khair Khan (reigned 1428–68), the Jochid ruler of the Kazakh steppe in the mid-fifteenth century CE, was a new name for the ulus of Jochi, which included the proto-Kazakhs of the Kazakh steppe. Therefore, one should bear in mind that the ulus of Urus Khan and of Abū al-Khair Khan were both called Uzbek without distinction by their contemporaries. Similarly, the ulus of Jānībeg Khan and Girāy Khan, great-grandsons of Urus Khan, and that of Muḥammad Shībānī Khan (reigned 1500–10), grandson of Abū al-Khair Khan, were also regarded as belonging to the same Uzbek ulus by their contemporaries at the turn of the sixteenth century CE. For instance, Muḥammad Ḥaidar Dughlāt, a member of the Dughlat/Dulat tribe, refers to the ulus of Jānībeg Khan and Girāy Khan not only as ‘Qazaq’, but also as ‘qazaq Uzbeks (Uzbak-i qazāq)’ in his Tārīkh-i Rashīdī. As for the Uzbeks headed by the Abū al-Khairid clan, he calls them ‘Shibanid Uzbeks (Uzbak-i Shībān)’.i

Further, Muḥammad Ḥaidar Dughlāt describes a Moghul victory over the Kazakhs as ‘a triumph over the Uzbeks’ or refers to the domain of the Kazakh ruler Tāhir Khan (reigned 1523–33) as ‘Uzbekistan (Uzbakistān)’. Similarly, Fażlallāh b. Rūzbihān Khunjī, the court historian of Muḥammad Shībānī Khan, also identifies the Kazakhs with the Shibanid Uzbeks in his Mihmān-nāma-i Bukhārā, which provides an eyewitness account of Muḥammad Shībānī Khan’s third campaign against the Kazakhs in 1508–9. Khunjī writes that there were three branches (ṭāyifa) that ‘belong to the Uzbeks (mansūb bi-Uzbak)’: the Shibanids (Shibānīyān), the Kazakhs (Qazāq), and the Manghit.

Modern Kazakhs are not direct descendants of the Saks (Scythians), Usuns, Huns and Turks.

Consequently, Khunjī writes that ‘the Kazakhs are a branch of the Uzbeks (Qazzāq yik ṭāyifa az Uzbak-and)’. Like Muḥammad Ḥaidar Dughlāt, he refers to the Shibanids and the Kazakhs as ‘Shibanid Uzbeks (Uzbakān-i Shībānī)’ and ‘qazaq Uzbeks (Uzbakān-i Qazzāq)’ respectively. Khunjī also deplores the fact that the Kazakhs and the Shibanids sell each other into slavery, treating their ‘own people (qaum-i khūd)’ as war booty. He also identifies the two groups by stating that ‘there is constant strife and conflict among the Uzbek khans, especially among the Shibanid khans and the Kazakh khans (Miyān-i khānān-i Uzbak hamīsha munāzaʿat va mujādala ast khuṣūṣan miyān-i khānān-i Shībānī va khānān-i Qazzāq).’

Importantly, Qādir ʿAlī Bek Jalāyirī, who was himself from the Kazakh Jalayir tribe, refers to the Kazakh ulus as Özbäkya in the dāstān (tale) of Urus Khan (which provides a brief account of the Kazakh khans), which is included in his Jāmiʿ al-tavārīkh. For instance, listing the names of Kazakh khans such as Jānībeg Khan and Barāq Khan, Jalāyirī states that a certain Aḥmad Khan ‘is called Aqmat Khan by the Uzbeks (Özbäkya Aqmat Ḫān tib eyürlär)’.1

As a matter of fact, the proto-Kazakhs also included the eastern Chaghatayid ulus, who were identified by others and themselves as Moghul. In the sixteenth century CE, the expanding Kazakhs incorporated the Moghul nomads inhabiting southeastern Kazakhstan (and the Manghit/Nogai nomads residing in western Kazakhstan) into their ulus. The Chaghatayid ulus were descended from the army units given to Chaghatay Khan (reigned 1227–1241) by his father, Chinggis Khan (reigned 1206–1227). The Chaghatayid ulus became divided into the eastern and western sections from the 1340s. According to Muḥammad Ḥaidar Dughlāt, while the latter, centered in Transoxiana, the oasis region between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, used Chaghatay as their self name, the former, residing in Moghulistan (‘land of the Mongols’ in Persian), the grassy plain between Lake Balkhash and the Tian Shan Mountains, modern-day southeastern Kazakhstan, used ‘Moghul’ (Mongol in Turkic) to refer to themselves. Muḥammad Ḥaidar Dughlāt, who is now regarded as a (Dughlat/Dulat) Kazakh ancestor in Kazakhstan, belonged to the Moghul ulus.

In short, what the primary sources produced in central Asia during the post-Mongol period tell us is that the proto-Kazakhs who developed into the Kazakhs at the turn of the sixteenth century CE were the Jochid and Chaghatayid uluses rather than an amalgamation of all the nomadic peoples that had inhabited the steppes of Kazakhstan since the Bronze Age. This means that the modern Kazakhs are not lineal descendants of the Saka (Scythians), Wusun, Xiongnu, and Türks. These Iranic and Turkic groups should be viewed as being indirectly related to the modern Kazakhs only through the Jochid and Chaghatayid uluses.

N.K. Roerich. The holder of the cup. 1937 / Alamy

Concerning the origins of these two Chinggisid uluses (and thus the proto-Kazakhs), they arose from the merging of various inner Eurasian groups and the Mongols in the thirteenth century CE under Chinggisid leadership. Let me briefly talk about this ethnogenetic process. First, the original Mongols, who made up Chinggis Khan’s kindred tribes, such as the Barlas (Barulas), Qunghrat (Qunqirat), Manghit (Mangqut), Dughlat, and Ushin, among others, merged with non-Mongol Mongolic-speaking peoples, such as the Kereit, Jalayir, Oirat, and Tatar, among others, and Turkic-speaking peoples, such as the Naiman, Önggüt, and Uyghurs, among others, who lived in and around the Mongolian steppe. The British Persianist David Morgan once characterized the nomadic groups inhabiting the Mongolian steppe at the turn of the thirteenth century CE as ‘Turko-Mongols’. It was a very multi-linguistic entity that formed the new Mongol ulus of Chinggis Khan.

Accordingly, the Secret History of the Mongols, the famous thirteenth-century CE Mongol history of Chinggis Khan and his ancestors, refers to the new Mongol ulus as ‘the people of the felt-walled tents,’ that is, ‘nomads’. The Jāmiʿ al-tavārīkh, a universal history compiled for the Ilkhanid Mongol rulers of Iran by Rashīd al-Dīn (died 1318), classifies them into two new and one original Mongol groups:

1) ‘The tribes of the Turks that are now called Mongol, but in the older times each of which had its own name and each of which had a separate sovereign and a commander and from which separate groups and tribes were created and have remained (aqvāmī az Atrāk ki īshān-rā īn zamān Mughūl mīgūyand lākin dar zamān-i qadīm har yik qaum az īshān ʿalā al-infirād bi-lughatī va ismī makhṣūṣ būda va har yik ʿalā-ḥidda sarvarī va amīrī dāshta va az har yik shuʿab va qabāʾilī munshaʿib gashta mānand)’;

2) ‘The Turkic tribes that have also had separate monarchs and leaders but who do not have a close relationship to the tribes mentioned in the previous chapter or to the Mongols yet are close to them in physiognomy and language (aqvāmī az Atrāk ki īshān nīz ʿalā-ḥidda, pādshāhī va muqaddamī dāshta-and lākin īshān-rā bā aqvāmi Atrāk ki dar faṣl-i sābiq yād karda shuda va bā aqvām-i Mughūl, ziyādat-i nisbatī va khvīshī qarīb al-ʿuhda nabūda, ammā bā shakl va zabān bā īshān nazdīk būda-and)’; and

3) ‘The Turkic tribes that were anciently styled Mongol (aqvāmī az Atrāk ki dar zamān-i qadīm laqab-i īshān Mughūl būda…).’ The nascent Mongol ulus went on to incorporate other Turkic (the Qangli and Qipchaq among others) and Mongolic (the Qara Khitai) peoples residing in and around the Qipchaq steppe and, by the middle of the thirteenth century CE, formed four major Chinggisid uluses: the Mongols of the Yuan dynasty, the Mongols of the Ilkhanate, the Jochid ulus, and the Chaghatayid ulus.

Specifically, the Jochid ulus consisted of

1) tribes of Mongol origin (the Manghit, Qunghrat, Arlat, Barin, Barlas, Durman, Keneges, and Ushin, among others);

2) tribes of non-Mongol Mongolic and Turkic origins from the Mongolian steppe (the Jalayir, Qara Khitai, Kereit, Naiman, Oirat, Öngüt, Tatar, and Uyghur, among others);

3) indigenous Turkic tribes of the Qipchaq steppe (the Qipchaq and Qanqli, among others); and

4) newly formed or named tribes within the Mongol empire (the Arghun, among others).

The Chaghatayid ulus in the mid-fourteenth century CE consisted of

1) tribes of Mongol origin, such as the Barlas, Arlat, Suldus, and Dughlat, among others;

2) tribes of non-Mongol origins, such as the Jalayir; and

3) some newly formed or named groups within the Mongol empire, such as the Qara’unas.

As a result, the modern Kazakhs came to consist of

1) tribes of Mongol origin (the Dughlat/Dulat, Manghit, Qunghrat, and Ushin, among others);

2) tribes of non-Mongol Mongolic and Turkic origins from the Mongolian steppe (the Jalayir, Kereit/Kerey, and Naiman, among others);

3) indigenous Turkic tribes of the Qipchaq steppe (the Qipchaq and Qangli, among others); and

4) newly formed or named tribes within the Mongol empire (the Arghin, among others).

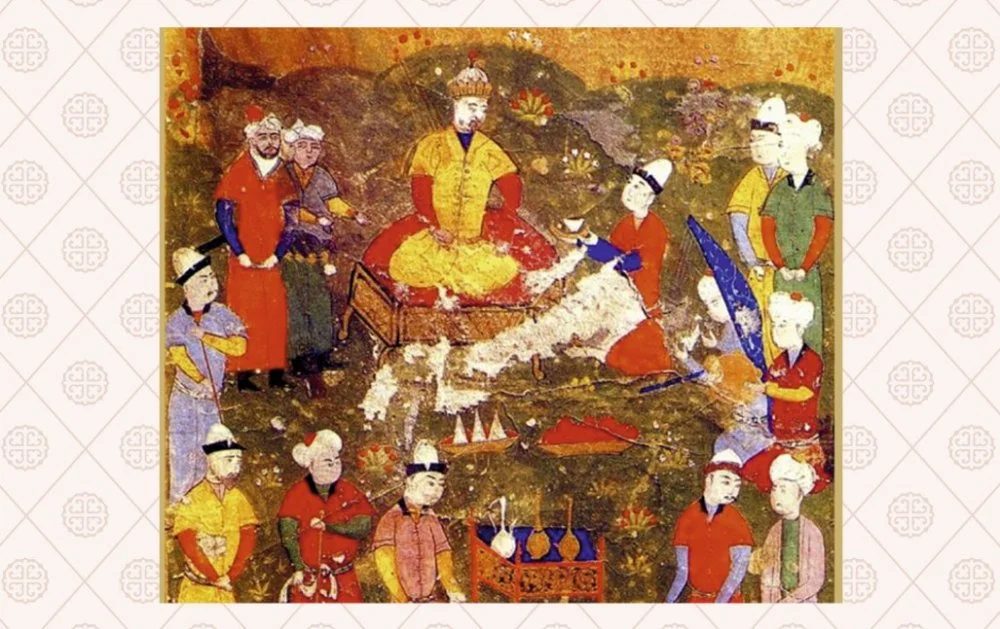

Abulkhair Khan (Uzbek Khanate). Miniature from a 16th century uzbek manuscript / Wikimedia Commons

Qazaqlïq and the Formation of Qazaq Identity

What is qazaqlïq? Why does qazaqlïq matter in central Eurasian history in general and in Kazakh history in particular? The word qazaqlïq is made up of the term qazaq and the suffix -lïq/-lik, which indicates occupation and length of time.2

Wolfgang Holzwarth provided a more detailed definition of the term qazaqlïq, drawing from some early sixteenth-century CE Turkic sources. He characterised qazaqlïq as the life of an adventurer, with the following meanings: wandering; raiding, plundering, guerrilla warfare; the life outside of the established political order; and the period during which a non-reigning prince demonstrates his talent as a leader and gathers followers. He defined qazaq as a participant in a band of freebooters, plunderers, or robbers. Stephen Frederic Dale defined qazaq as ‘a political vagabond’ and qazaqlïq as ‘throneless, vagabond times’ that displaced rulers, such as Babur, had to undergo, ‘wandering in the political wilderness, fighting for fortresses and kingdoms, or … trying to recover those they had lost.’ Maria Eva Subtelny similarly defined qazaq as ‘freebooter, brigand, vagabond, guerrilla warrior, and Cossack’ and qazaqlïq as ‘the period of brigandage that such an individual spent, usually as a young man, roaming about in some remote region on the fringes of the sedentary urban oases, usually after fleeing from a difficult social or political situation’.

Now, let me tell you how the term qazaq was actually used in primary sources. In Timurid and post-Timurid central Asian sources, qazaq was generally used in the sense of ‘a vagabond/wanderer’ and/or ‘a brigand/freebooter’. In the western Qipchaq steppe (the Black Sea steppe), the Volga region, and eastern Europe (Russia, Ukraine, and Poland), various sources written in Turkic, Slavic, and Latin used the terms qazaq, kazak, and kozak in a broader sense to denote ‘a political dissident’, ‘a fugitive/runaway’, as well as ‘a vagabond/wanderer’ and/or ‘a brigand/freebooter’. In the primary sources produced in the post-Mongol period, qazaqlïq thus denoted a form of political vagabondage that involved fleeing from one’s state or tribe and/or living the life of a freebooter in a frontier or remote region. In theory, qazaqlïq was made up of three phases. In the first stage, a political dissident chooses to desert his own state or tribe to pursue survival or with the aim of returning or coming to power, an action which is appropriately reflected in the use of the term qazaq/kazak by (Crimean and Volga) Tatar and Muscovite writers in the sense of ‘a dissident’ or ‘a fugitive’. In the second, this political runaway wanders around, with his qazaq companions, often engaging in brigandage (to secure provisions) in a frontier or a remote region; and in third, as a charismatic qazaq leader, this political vagabond succeeds in mustering new followers and rises or returns to power.

Let me now talk about the historical importance of qazaqlïq. First, it played an important role in state formation in post-Mongol central Eurasia. Notably, Temür, Muḥammad Shībānī Khan, and Babur, who founded the Timurid empire, Uzbek Khanate, and Mughal empire respectively, all experienced periods of political vagabondage in their careers before coming to power. To escape political adversity and wait for an opportune moment to return or rise to power, they, along with their followers, had to separate themselves from their own states, and wander in remote regions or in foreign lands, acquiring their means of living by plundering. During these periods, they mustered a loyal band of warriors, thanks to which they were able to rise to power.

Second, qazaqlïq also played a crucial role in the formation of the Kazakhs as a separate nomadic people (ulus) at the turn of the sixteenth century CE. More specifically, the Kazakhs came into existence when the Jochid ulus (Uzbeks) of the Kazakh steppe became divided into the qazaq Uzbeks (later Qazaqs) and the Shibanid Uzbeks as a result of the conflictual and interrelated qazaqlïq activities of Jānībeg Khan and Girāy Khan on the one hand and of Muḥammad Shībānī Khan on the other.

Modern Kazakhs would still be called uzbeks and identified as uzbeks if it were not for the custom of cossackization.

This process began when the Uzbeks led by Jānībeg Khan and Girāy Khan, two great-grandsons of Urus Khan, broke away from Abū al-Khair Khan’s Uzbek state in the mid-fifteenth century CE and was completed when the Uzbeks led by Muḥammad Shībānī Khan, the grandson of Abū al-Khair Khan, conquered the Timurid states of Transoxiana and Khorasan and settled in the central Asian oases in the early sixteenth century CE. I would like to emphasize here that prior to the two qazaqlïq activities of the Urusid and the Abū al-Khairid clans, the proto-Kazakhs were still ‘Uzbeks’. When Jānībeg Khan and Girāy Khan first separated themselves from Abū al-Khair Khan and moved to Moghulistan with their followers, they began to be called qazaq Uzbeks. At that time, their Kazakh (Qazaq) identity was basically an anti-Abū al-Khairid political identity, not an ethnic identity. The Kazakh identity became consolidated and turned into a separate identity because of the long conflict between the Urusid and the Abū al-Khairid clans, which involved the qazaqlïqs of Jānībeg Khan and Girāy Khan on the one hand and Muḥammad Shībānī Khan on the other. Without Jānībeg Khan and Girāy Khan’s qazaqlïq, the proto-Kazakhs would have retained the ethnonym Uzbek and their Uzbek identity. Equally, without the qazaqlïq of Muḥammad Shībānī Khan and the establishment of the Abū al-Khairid dynasty (Uzbek khanate) in Transoxiana, which led to the complete bifurcation of the Uzbeks of the Kazakh steppe, the qazaq Uzbeks, that is, the future Kazakhs, may have remained Uzbeks rather than eventually adopting the ethnonym Qazaq as a self-appellation. Then, modern Kazakhs would still be called and identified as Uzbeks, just as Urus Khan, Toqtamïsh Khan, Abū al-Khair Khan, Muḥammad Shībānī Khan, Jānībeg Khan, and Girāy Khan were all called so and viewed as belonging to the same Jochid ulus by their contemporaries. Therefore, the emergence of the Kazakhs as a separate nomadic identity or ulus should be viewed as being the outcome of the combination of the two consecutive qazaqlïq activities (circa 1450–70 and ca. 1470–1500) led by two rival Chinggisid/Jochid clans.

I mentioned earlier that the Uzbeks led by the Abū al-Khairid clan were called ‘Shibanid Uzbeks’ by their contemporaries because Abū al-Khair Khan was descended from Shībān, fifth son of Jochi (died 1225 or 1227). I would like to emphasize here that one should differentiate between the Shibanid Uzbeks and the modern Uzbeks. After the Shibanid Uzbeks led by Muḥammad Shībānī Khan and other Abū al-Khairids conquered the Timurid states of Transoxiana and Khorasan at the turn of the sixteenth century CE, they formed the elite class ruling over the Tajiks, who were the local Iranic-speaking sedentary people of central Asia. Specifically, the Shibanid Uzbeks consisted of tribes of Mongol origin (the Manghit, Qunghrat, Arlat, Barin, Barlas, Durman, Keneges, and Ushin, among others), non-Mongol Mongolic and Turkic tribes from the Mongolian steppe (the Jalayir, Qara Khitai, Kereit, Naiman, Oirat, Öngüt, Tatar, and Uyghur, among others), indigenous Turkic tribes of the Qipchaq steppe (the Qipchaq, Qanqli, and Qarluq, among others), and the newly formed or named tribes within the Mongol empire (the Arghun, among others).

However, the modern Uzbeks came into existence in 1924, when the Soviet Union created the new Uzbek nation, tailoring nationalities to the Soviet national republics. In the process, the Soviet Union also bestowed the name Uzbek on various non-Uzbek (Persian- and Turkic-speaking) groups of modern-day Uzbekistan. As a result, modern Uzbeks consisted of not only Shibanid Uzbeks elements, but also Sarts (mostly groupings of Tajik origin who became Turkic speakers) and Tajiks, neither of whom had previously been regarded as Uzbeks. The Soviet Union also chose Qarluq Turkic (a language related to Chaghatay Turkic), not Qipchaq Turkic spoken by the Shibanid Uzbeks (and the Kazakhs), as the language of this new Uzbek nation. The modern Uzbeks can now be divided into the ‘joqchi Uzbeks’ and the ‘yo‘kchi Uzbeks’. The joqchi Uzbeks are close to the modern Kazakhs in terms of appearance and language. They are said to have a ‘Kazakh’ physiognomy, unlike other modern Uzbeks, and speak Qipchaq Turkic like the Kazakhs. Besides, the modern Uzbeks, who ‘chose’ the Timurids as their ancestors after their independence from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, do not consider the Shibanid Uzbeks their ancestors. What this means is that Shibanid Uzbeks are much closer to modern Kazakhs than to modern Uzbeks. We can even say that the real descendants of the Shibanid Uzbeks are the modern Kazakhs. If we are to choose a modern ethnonym for Abū al-Khair Khan, Muḥammad Shībānī Khan, and their Uzbek followers, Kazakh rather than Uzbek would suit them best.

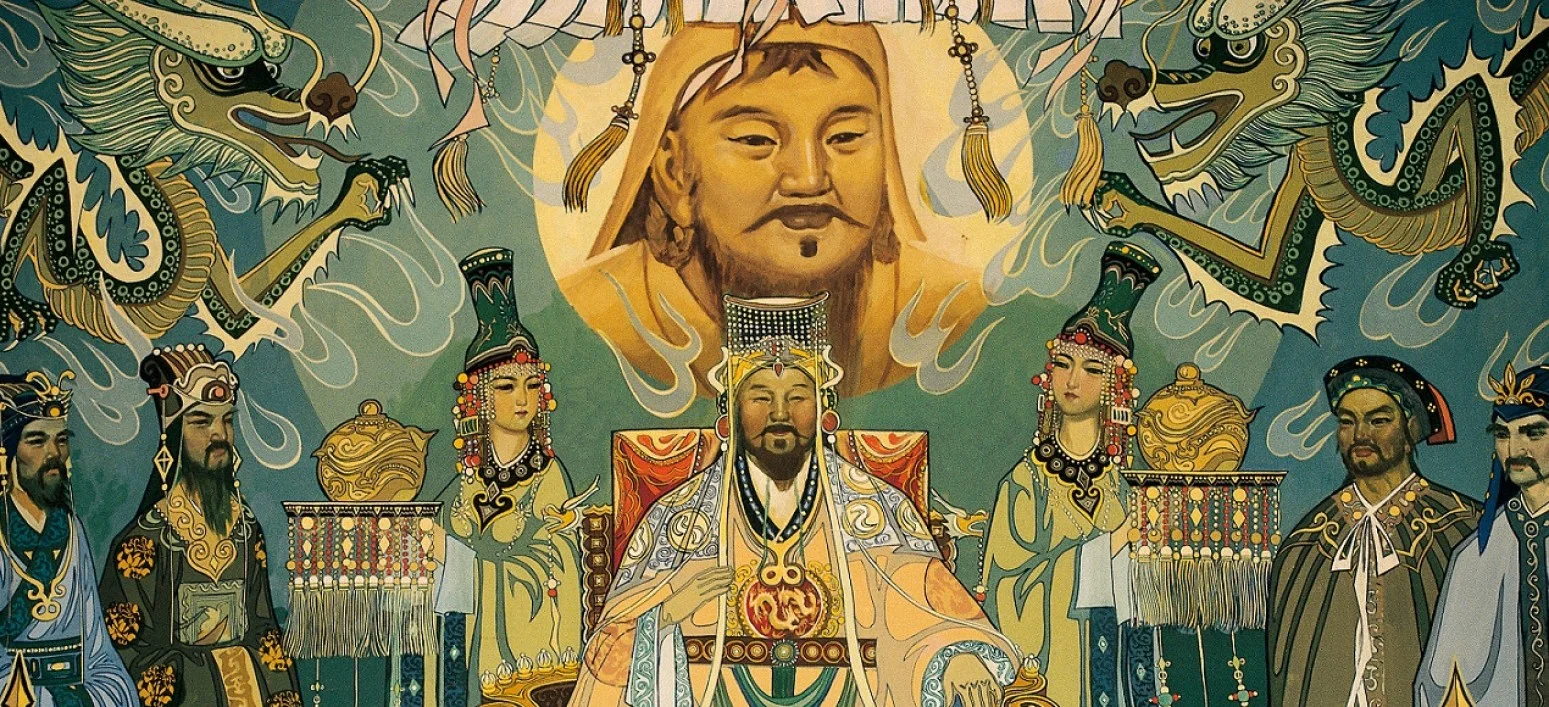

Was Chinggis Khan Kazakh or Mongol?

The progenitor of the Jochid and Chaghatayid uluses, from which the Kazakhs arose, was Chinggis Khan (reigned 1206–1227), who is regarded by many as the greatest conqueror of all time. I recall that a Kazakh taxi driver I met in Almaty in 2010 told me that Chinggis Khan was a ‘terrorist’ when I asked him what he thought of the conqueror. I am also aware that some amateur Kazakh historians view Chinggis Khan as Kazakh and not Mongol. This claim is not taken seriously by Western historians. As a matter of fact, genuine historians will never in a million years deny or question the fact that Chinggis Khan was a Mongol conqueror. However, as a specialist in central Eurasian history who has researched inner Eurasian nomadic peoples for the past twenty years, I can unreservedly say that Chinggis Khan should be identified as both Kazakh and Mongol if we are to apply modern ethnonyms to him (albeit anachronistically).

To explain my view on the identity of Chinggis Khan, let me first compare him with the Frankish ruler Charlemagne (reigned 768–814). The Franks were a Germanic-speaking people (from modern-day Belgium) who invaded the western Roman Empire in the fifth century CE. Their ruler Charlemagne succeeded in uniting much of western and central Europe in the late eighth century CE. However, after the death of Charlemagne’s son and successor Louis I (778–840), the Frankish empire became divided into West Francia, Middle Francia, and East Francia. While Middle Francia was short-lived, West Francia became the kingdom of France (thus France), and East Francia became the Holy Roman Empire from which Germany later arose. The descendants of the Franks now reside in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and western Germany. One may thus argue that Charlemagne laid the foundations for modern France and Germany (as well as the Low Countries). In other words, both France and Germany can lay claim to the legacy of Charlemagne. If we are to use modern ethnonyms to refer to Charlemagne, many will identify him as both French and German. We should also understand why French historians have presented him as a French monarch even though Charlemagne is said to have spoken Old Franconian, which was a west Germanic language, and Latin, not Old French. Before conquering large parts of Germany and Italy, Charlemagne was king of the Frankish state, which had had its center in the region of Paris since the early sixth century CE. Besides, the name ‘France’ is derived from the Franks.

Jean-Victor Schnetz. Charlemagne receives Alcuin. 1830 / Wikimedia commons

Like Charlemagne’s Frankish empire, which became modern-day France and Germany, Chinggis Khan’s empire became modern-day Kazakhstan and Mongolia. Likewise, Chinggis Khan’s ulus became the modern Kazakhs and Mongols. Here, one should not equate the Mongol ulus of Chinggis Khan with the modern Mongols. The name ‘Mongol’ is now used synonymously with Mongolic-speakers, who include the Mongolians, Buryats, and Kalmyks. However, the Mongol ulus of the Mongol and post-Mongol periods were a more complex people. It denoted the nomads who, after being united by Chinggis Khan, participated in the Mongol enterprise and later came to constitute the Chinggisid uluses. As mentioned earlier, they arose from the merging of the original Mongols, who made up Chinggis Khan’s kindred tribes, non-Mongol Mongolic-speaking peoples, and Turkic-speaking peoples living in and around the Mongolian steppe. The Mongol ulus also incorporated other Turkic and Mongolic peoples living in and around the Qipchaq steppe by the mid-thirteenth century CE. As discussed above, the Jāmiʿ al-tavārīkh classifies the Mongol ulus of the thirteenth century CE into two ‘new’ and one ‘original’ Mongol groups.

Importantly, the Chinggisid uluses were identified as both Mongol and Turk in the pre-modern Islamic world by their contemporaries, including Rashīd al-Dīn, the author of the Jāmiʿal-tavārīkh. There are numerous examples of Muslim writers who referred to the Mongols as Turks in their works. For instance, the renowned Arab historian Ibn al-Athīr’s (died 1233) describes the Mongols as Turks thus: ‘There remained some Turks who had not converted (to Islam), the Tatars and the Chinese (wa baqā min al-Atrāki man lam yaslam Tatar wa Khaṭā).’ Similarly, Amīr Khusrau, a celebrated poet of the Delhi sultanate, writes in his work that the Mongols are ‘Turks of the tribe of Qai and the eaters of vomit (qai)’. Likewise, Ibn Baṭūṭah (died 1377), the Moroccan traveler who made an extensive tour around the Mongol empire in the fourteenth century CE, refers to the Mongols of the Chaghatayid khanate and the ulus of Jochi in his travelogue as Turks. The great Arab historian Ibn Khaldūn (died 1406) also defines the Mongols as being ‘a branch of Turks (min shuʿūb al-Turk)’ in his works.

One should bear in mind here that Turk in the pre-modern Islamic world denoted an inner Asian nomadic identity, not a Turkic identity in the modern sense. Muslim writers used the name Turk (plural Atrāk) virtually as a synonym for inner Asian nomads, including non-Turkic-speaking nomadic groups. Most notably, the Persian Muslim historian al-Ṭabarī (died 923) identified the Turks as (Noah’s son) Japheth’s descendants, who are ‘fullfaced with small eyes (ʿaẓīm al-wajh ṣaghīr al-ʿaynayn)’ and not as ‘Turkic-speaking’ groups. Similarly, Muslim geographers such as Marvazī and Gardīzī viewed virtually all the peoples residing in the steppes north of the Syr Darya, including some Finno-Ugrian and Slavic peoples, as Turks irrespective of their linguistic background.

In the mongol and post-mongol periods, various turkic-speaking nomadic groups and mongols were considered as one and the same people in Iran and Central Asia.

Consequently, in Iran and central Asia during the Mongol and post-Mongol periods, Turk came to be used as a term related to Tajik, meaning sedentary Iranian speakers. Importantly, it encompassed Mongol. For instance, the phrase ‘Turk and Tajik (Turk u Tāzīk)’ was used in Ilkhanid histories and documents to denote both sedentary and nomadic populations. Turk in this expression primarily denoted the Mongols. Like al-Ṭabarī, Rashīd al-Dīn argued that all the nomadic Turks (Atrāk-i ṣaḥrā-nishīn), including the Mongols, were descended from Japheth (Yāfas) through the latter’s son Dīb Bāqūy. The Timurid court historian Sharaf al-Dīn ʿAlī Yazdī (died 1454) also argued that the Timurids and the Chinggisids, both of whom he viewed as Mongol, were descended from Mongol (Mughūl) Khan, a great-great-great grandson of Turk Khan, son of Japheth. According to Yazdī’s genealogy, the Timurids and the Chinggisids belonged to the Mongol branch of the Turks.

In short, the various Turkic-speaking nomadic groups and the Mongols were regarded as the same people in Iran and central Asia during the Mongol and post-Mongol periods. What this signifies is that the ‘proto-Kazakhs’ who inhabited the Kazakh steppe during the post-Mongol period, that is, the Uzbeks, could readily be identified as Mongol by their contemporaries despite being Turkophone. For instance, the Timurid historian Naṭanzī refers to the Uzbek amirs as Mongol in his work. He writes: ‘When Jalāl al-Dīn Sulṭān, son of Toqtamïsh Khan, gave complete power to the Tāzīks in his assembly, the Mongol amirs became weak and seduced Jalāl al-Dīn Sulṭān’s brother to revolt.’ Muḥammad Shībānī Khan also calls himself Mongol in a ghazal that he wrote in Chaghatay Turkic. Perhaps the identification of the Uzbeks of and from the Kazakh steppe with the Mongols is best exemplified in the Baḥr alasrār fī manāqib al-akhyār, a mid-seventeenth-century CE encyclopedic work produced in the Uzbek khanate. Concerning the inhabitants of Turkistan (the steppes north of Syr Darya), it states: ‘The people of Turkistān were called Turks from the time of Japheth’s son Turk to the time of Mongol Khan; after the rule of Mongol Khan, they were called Mongols; after the reign of Uzbek Khan, the inhabitants of that land were called Uzbeks.’

One may still ask, ‘Did Chinggis Khan and his immediate followers not speak Mongolian unlike the Uzbeks (Jochid ulus) and the Moghuls (Chaghatayid ulus) of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries CE who spoke Turkic?’ I would like to emphasize here that, in the steppe world, language was not an important factor in identity formation. Inner Asian nomads often adopted the identities of their ruler. They also emphasized their tribal lineages. This point is well exemplified in the words of ʿAlīshīr Navāʾī (died 1501), a poet and scholar in the Timurid court in Herat, who identified himself as Turk. It is well known that Navāʾī argued that the Turkic language was a proper literary language superior to Persian in his Muhäkamat al-lughatain. However, Navāʾī writes in the same work: ‘The fortune (rūzgār) was transferred from the Arab kings (malik-i ʿArab) and the Iranian rulers (Sart ṣalāṭīni) to Turkic khans (Türk khānlar). From the time of Hülegü Khan and from the time of Temür to the end of the reign of his son and successor, Shāhrukh, verses in Turkic were composed …’ Here, Navāʾī views Hülegü Khan (reigned 1259–65), grandson of Chinggis Khan and the founder of the Ilkhanate, not only as a Turk, but also the first Turkic khan in the Islamic world.

In contrast, Navāʾī refers to the (Oghuz Turkic-speaking) Seljuk ruler Ṭughril Beg as ‘an Iranian ruler (Sart sulṭān)’ in the same work. Similarly, Ulugh Beg (reigned 1447–49), the grandson of Temür, does not equate language with ethnicity in his Tārīkh-i arbaʿ ulūs, a history of the Mongol empire. More specifically, he does not define Turk as a Turkic speaker or Mongol (Mughul) as a Mongolic speaker. Therefore, while identifying Chinggis Khan (and also the Timurids) as Mongol, Ulugh Beg presents him as a Turkic speaker. According to Ulugh Beg, Chinggis Khan and one of his amirs conversed in Turkic about his son Jochi’s death. When the news of Jochi’s death reached Chinggis Khan’s camp, a Mongol amir reported this to Chinggis Khan in Turkic, and the latter also lamented in Turkic. Here, I am not arguing that Chinggis Khan actually knew or spoke Turkic.

What all this means is that in the Islamic world during the Mongol and post-Mongol periods, ‘Turks’ and ‘Mongols’ were not differentiated from each other based on language. The nomad followers of Chinggis Khan and the Chinggisids were all considered Mongol, while the Mongols were identified as Turks. There was no division between Turk and Mongol in the ulus of Jochi and the Kazakh khanate. In short, Chinggis Khan’s Mongol ulus and the proto-Kazakhs were never distinguished from each other by their contemporaries. They were viewed as belonging to the same people. Language did not play a role in the process whereby Chinggis Khan’s Mongol ulus became Kazakhs.

We may also ask ourselves these questions: If Chinggis Khan rose from the dead, would he identify himself as Kazakh or Mongol? As a Mongolic-speaker himself, would he not side with the Mongolic-speaking Oirats rather than the Turkic-speaking Kazakhs if he considered the wars between the Kazakhs and the Zunghars? As for the first question, we should think of what Charlemagne would do if he were to rise from the dead. In all likelihood, he would identify himself as both French and German. As for the second question, we should think of how the Kazakhs and the Zunghars were viewed by their contemporaries during the post-Mongol period. Importantly, the wars between the Chinggisid uluses (Kazakhs, Shibanid Uzbeks, Moghuls, and Crimean Tatars) and the Oirats were not seen as a conflict between Turks and Mongols by their contemporaries. Notably, the famous Ottoman traveler Evliya Chelebi (1611 to circa 1687), who visited the Oirats in the Volga region, the forebears of modern-day Kalmyks, in 1666, differentiated between the Oirats and the Mongols. Specifically, he used the term ‘Qalmaq’ for the Oirats and reserved the name Mongol for Chinggis Khan. Importantly, he regarded the Crimean Tatars, who were headed by a Chinggisid dynasty, and not the Oirats, as true heirs of Chinggis Khan and the Mongols. Therefore, the wars between the Kazakhs and the Oirats were seen as a conflict between a Chinggisid ulus and Qalmaqs (never as a conflict between Turks and Mongols) by their contemporaries.

As I mentioned previously, in the steppe world, a close linguistic affiliation between certain nomadic groups did not necessarily create a sense of common ethnic identity between them. Therefore, even though the Oirats and the Northern Yuan Mongols were both Mongolic-speaking peoples, they did not share a sense of common ethnic identity in the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries CE. The two peoples had separate origins from the beginning. When Chinggis Khan founded the Mongol ulus in 1206, the Oirats, who inhabited the forest region of northwestern Mongolia, were still not included in it. In the Secret History of the Mongols, the Oirats are referred to as ‘the People of the Forest (oy-yin irgen)’ and not as Mongols. From the turn of the fifteenth century CE, the Oirats began to challenge the northern Yuan Mongols led by Chinggisid khans, who had been ousted from China by the Chinese Ming dynasty in 1368.

Unlike the early Oirats, the fifteenth-century CE Oirats formed a tribal confederation known as the Dörbön Oyirad, or Four Oirat, mostly made up of the original Oirat and other non-Mongol peoples. The two sides were engaged in constant warfare with each other between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries CE. Although referred to as ‘western Mongols’ by some modern historians, the Oirats did not identify themselves as Mongol. The Northern Yuan Mongols did not regard the Oirats as Mongols either. For instance, the seventeenth-century CE Mongolian chronicles, such as the Erdeni-yin tobči and the Altan tobči, describe the Oirats as a distinct people from the Mongols, calling them qari daisun, meaning ‘foreign enemies’. The Oirat histories also depict the northern Yuan Mongols as being distinct from the Oirats. For instance, the Dörbön Oyirodiyin Töüke, written in 1737, treats the Oirats and the northern Yuan Mongols as two separate peoples, referring to the former as Dörbön Oyirod (Four Oirat) and the latter as Döčing Mongγol (Forty Mongol). The Dörbön oyirad Mongγolyigi Daruqsan Tuuji, a seventeenth-century CE Oirat history that describes the 1623 Mongol-Oirat battle that resulted in the rise of the Zunghars, begins its account of the battle by relating that the 80,000-strong Mongols army attacked ‘the alien Four Oirats (qari dörbön oyirad)’ and sums it up by stating that ‘this is the way the Four Oirat defeated the Mongols (dörbön oyirad mongγoli daruqsan ene)’. Likewise, the Zunghar Oirat ruler Galdan (1644–97) calls the northern Yuan Mongols ‘enemies’ in a letter that he wrote to the Russian tsar in 1691. He writes: ‘Because the Mongols are indeed enemies to us and to you, I have requested that you issue an order …’ Thus, it should not come as a surprise that Esen Taishi (reigned 1439–54), who founded a short-lived Oirat empire in the mid-fifteenth century CE, even attempted to kill all the Chinggisids of Mongolia in 1452. In contrast, the Kazakhs were proud of their Chinggisid legacy, a fact that I do not need to explain here. With all these factors being considered, one can safely predict whom Chinggis Khan would view as his successors if he were to rise from the dead.

Alua Tebenova. Hunters. 2022

In this essay, I attempted to provide a critical discussion of Kazakh ethnogenesis and identity. Basing my arguments on the historical evidence found in primary sources, not on conjecture (or any ideological preference), I presented the following conclusion: the proto-Kazakhs were none other than the Jochid ulus, or people, who were identified as Uzbeks by their contemporaries; the Kazakhs came into existence as a separate ulus when the Uzbeks of the Kazakh steppe became divided into the qazaq Uzbeks (Qazaqs) and the Shibanid Uzbeks as a result of the conflictual and interrelated qazaqlïqs of Jānībeg Khan and Girāy Khan on the one hand and of Muḥammad Shībānī Khan on the other. Chinggis Khan, the progenitor of the Jochid/Uzbek ulus (hence Kazakhs), can be identified as both Kazakh and Mongol (if we are to apply modern ethnonyms to him), just as the Uzbeks (hence Kazakhs) and Chinggis Khan’s Mongol ulus could be viewed as belonging to the same people by their contemporaries.