In his scientific works, Charles Darwin repeatedly and extensively expressed his views not only on nature and science, but also on human beings, their thinking, and their behavior. In his letters and autobiography, he also explained in great detail how he thought, worked, and lived. Here are Darwin’s rules for life.

Don't Waste Time

‘A man who dares to waste one hour of time has not discovered the value of life,’ Darwin wrote in a letter to his sister from Brazil shortly before returning home on the HMS Beagle.

And indeed, Charles Darwin was not known for wasting time, at least not at a more mature age. As a student, of course, he spent his time idly, and thus, he speaks from knowledge. Since 1842, he had lived and worked at home, on an estate in the village of Downe, then about twenty kilometers from London. His son Francis described his daily schedule, from which Darwin rarely deviated, reproduced here.

Work Is the Best Medicine.

‘My chief enjoyment and sole employment throughout life has been scientific work; and the excitement from such work makes me for the time forget, or drives quite away, my daily discomfort,’ wrote Darwin, aged sixty-seven.

Darwin wasn't quite so healthy, that's for sure. Since the voyage of the HMS Beagle (1831–36), which helped Darwin formulate the theory of evolution, he had been experiencing a variety of physiological symptoms that could not be definitively explained either by the doctors of his time or by modern doctors. These symptoms had a major impact on his life and work, even if they did not prevent him from living to the ripe (even by today's standards) age of seventy-three. Also, he felt that ‘even ill-health, though it has annihilated several years of my life, has saved me from the distractions of society and amusement’.

This was written by a man who, in his youth, had spent a great deal of time in pursuits of amusement, especially hunting. Actually, as early as the Beagle voyage, at the age of twenty-four, Darwin's love of science overcame all other inclinations: ‘During the first two years [of the five-year voyage] my old passion for shooting survived in nearly full force, and I shot myself all the birds and animals for my collection; but gradually I gave up my gun more and more, and finally altogether, to my servant, as shooting interfered with my work, more especially with making out the geological structure of a country. I discovered, though unconsciously and insensibly, that the pleasure of observing and reasoning was a much higher one than that of skill and sport. The primeval instincts of the barbarian slowly yielded to the acquired taste of the civilized man.’

It’s Wrong to Torture Animals.

Because ‘the love for all living creatures is the most noble attribute of man’, since ‘there is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties’.

So what, no experiments on animals? What about science? Well, actually, you can do it, but ‘it is justifiable for real investigations on physiology; but not for mere damnable and detestable curiosity’.

Indeed, it was difficult to do without experiments on animals at that time, and Darwin himself conducted such experiments and used the results of other scientists' research in his own work. This did not prevent him, contrary to his custom of avoiding any kind of public discussions, from joining the campaign for legislation against cruelty to animals and to restrict vivisection (in particular, it was proposed that vivisection should be performed only under anesthesia, or be banned altogether) that developed in Britain in the early 1870s and culminated in the passage of a law that allowed animal experimentation only for the purposes of scientific research and education.

You Have an Idea, Write It Down.

Or the idea will fly away and you won't catch it. In the section of his autobiography devoted to the analysis of his own thinking, Darwin wrote: ‘Formerly I used to think about my sentences before writing them down; but for several years I have found that it saves time to scribble in a vile hand whole pages as quickly as I possibly can, contracting half the words; and then correct deliberately. Sentences thus scribbled down are often better ones than I could have written deliberately.’

One should be especially alert to thoughts and facts that contradict established beliefs. In discussing the success of his magnum opus, On the Origin of Species, Darwin wrote that he had followed this golden rule for many years: ‘Whenever a published fact, a new observation or thought came across me, which was opposed to my general results, to make a memorandum of it without fail and at once; for I had found by experience that such facts and thoughts were far more apt to escape from the memory than favorable ones. Owing to this habit, very few objections were raised against my views which I had not at least noticed and attempted to answer.’

Charles Darwin at home. 1887 / Alamy

Avoid Bias. Don't Be Afraid to Change Your Mind.

‘I have steadily endeavored to keep my mind free so as to give up any hypothesis, however much beloved (and I cannot resist forming one on every subject), as soon as facts are shown to be opposed to it. Indeed, I have had no choice but to act in this manner, for with the exception of the Coral Reefs, I cannot remember a single first-formed hypothesis which had not after a time to be given up or greatly modified,’ Darwin wrote in his autobiography at the end of his life.

Interestingly, he developed his theory of coral reef formation during his voyage on the HMS Beagle, shaped by the findings and outcomes of the voyage. This theory states that reefs begin to grow on continental shelves around an island or volcano and rise to the surface of the sea. Then, through geological processes, the volcano sinks below sea level while the reef remains, forming an atoll. This theory was confirmed by geologists more than half a century after Darwin’s death.

Be Methodical

‘My habits are methodical, and this has been of not a little use for my particular line of work,’ Darwin recalled. Ever since his youth, he had successfully applied this rule in practice, not only in scientific research, but also in solving problems in his personal life. For example, after proposing to his cousin and future wife, Emma Wedgwood, he carefully wrote down all the pros and cons of marriage in his diary and came to the conclusion that it was better to marry. The analysis worked out well: they lived together for thirty-three years, and Emma gave birth to ten children.

A person’s thinking process, he thought, should be controlled; after all, ‘the highest stage in moral culture at which we can arrive, is when we recognize that we ought to control our thoughts’.

How do you put this into practice? One way is to carefully collect, categorize, and organize facts. For example, Darwin kept a complete list of the books he had read (and those he had not read, although he thought he should), as well as of facts that might be useful to him. From the facts he collected, after thinking about them, he derived general laws that would explain those facts.

Read Poetry and Listen to Music

It is strange to hear this axiom from a scientist who had built his scientific career on synthesizing and analyzing countless facts and who urged people not to waste time. However, he believed that there must be room for fun in life, as is evidenced by his daily schedule. He made time for two games of backgammon every day!

Moreover, reading fiction and other ‘humanities’ material should always be given time, or Darwin believed there could be bad consequences. ‘Up to the age of thirty, or beyond it, poetry of many kinds, such as the works of Milton, Gray, Byron, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Shelley, gave me great pleasure, and even as a schoolboy I took intense delight in Shakespeare, especially in the historical plays. I have also said that formerly pictures gave me considerable, and music very great delight. But now for many years I cannot endure to read a line of poetry: I have tried lately to read Shakespeare, and found it so intolerably dull that it nauseated me. I have also almost lost my taste for pictures or music. Music generally sets me thinking too energetically on what I have been at work on, instead of giving me pleasure. I retain some taste for fine scenery, but it does not cause me the exquisite delight which it formerly did. […] This curious and lamentable loss of the higher esthetic tastes is all the odder, as books on history, biographies, and travels (independently of any scientific facts which they may contain), and essays on all sorts of subjects interest me as much as ever they did. My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts, but why this should have caused the atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the higher tastes depend, I cannot conceive. I had to live my life again, I would have made a rule to read some poetry and listen to some music at least once every week; for perhaps the parts of my brain now atrophied would thus have been kept active through use. The loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature.’

There Must Be Room for Foolishness in Life

He believed that foolishness should be accounted for in our lives in the form of scientific experiments. ‘I love fools’ experiments. I am always making them,’ Darwin once told the zoologist Edwin Ray Lankester.

For example, he once placed pollen from a male plant and a female flower at some distance under a glass cover to see if fertilization would occur. He also encouraged his colleagues to conduct such experiments: for example, to breed silkworms that did not produce silk. And when they themselves conducted ‘fools’ experiments’—like the German biologist Julius von Sachs’s experiment to feed chlorophyll-free leaves to green caterpillars to see if they would turn pale—he really welcomed them.

Not that Darwin expected pollen to somehow fertilize a flower in a confined space without drafts or pollinators, or that silkworms not producing silk would be of any use to anyone, but he did all this to be unbiased. Besides, in his opinion, fools’ experiments could somehow unexpectedly lead to real scientific results: ‘I am very fond of trying what I call “a fool’s experiment”; and such experiments, tho’ rarely successful in a direct manner, have often led to interesting side-results,’ he explained in a letter to the chemist James B. Hannay.

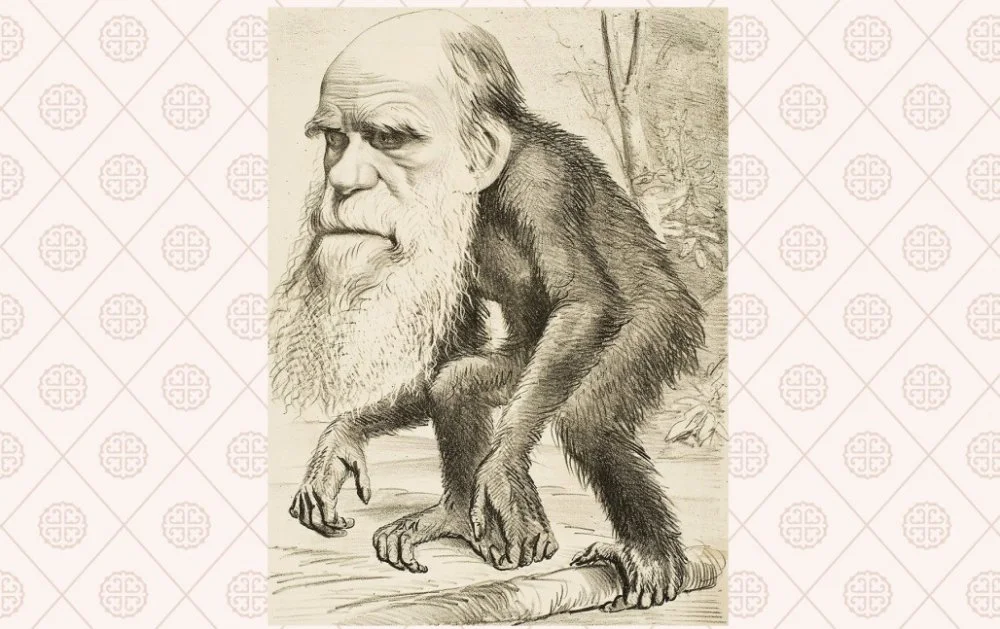

Caricature of Charles Darwin. 1871 /Illustration by GraphicaArtis/Getty Images

Let Everyone Believe What They Can

The question of Charles Darwin's attitude to the belief in God cannot be avoided, since he himself repeatedly addressed it. He gradually moved from a full confidence in the doctrines of faith, his plans to become a priest (for which it was necessary to go to university, and from there everything took a completely different turn), and being ridiculed by the crew of the HMS Beagle for his references to the Bible as an incontestable authority to a complete rejection of these views, which Darwin described in detail in a chapter of his autobiography.

At the same time, in a letter to the British missionary John Fordyce, he wrote that he had never been an atheist in the sense of denying the existence of God. And in a letter to the American botanist Asa Gray, discussing the controversy surrounding On the Origin of Species, he even wrote thus: ‘I cannot anyhow be contented to view this wonderful universe, and especially the nature of man, and to conclude that everything is the result of brute force. I am inclined to look at everything as resulting from designed laws, with the details, whether good or bad, left to the working out of what we may call chance. Not that this notion at all satisfies me. I feel most deeply that the whole subject is too profound for the human intellect. A dog might as well speculate on the mind of Newton. Let each man hope and believe what he can. Certainly I agree with you that my views are not at all necessarily atheistical.’