In the nineteenth century, Central Asia became the stage for ambitious, far-reaching imperial projects. As the Russian Empire advanced southward and established the Governor-Generalship of Turkestan, it absorbed a region shaped by traditionally Islamic societies, nomadic cultures, and their distinctive political structures. And along with imperial administrators, Orthodoxy entered the region as part of the new administrative order, immediately provoking outrage among local communities governed by very different norms. In this interview with Qalam, historian Daniel Scarborough explores how the Russian Orthodox Church adapted to this unfamiliar landscape, why imperial officials feared active missionary work, and what the juxtaposition of churches and mazars, or the mausoleums of saints, meant for all involved.

Daniel Scarborough / Qalam

Inventing ‘Russian Turkestan’

What was often referred to as Russian Turkestan was a vast territory colonized by the Russian Empire in the nineteenth century. The Governor-Generalship of Turkestan was formally established in 1867 after Russian forces conquered much of what is now Uzbekistan, southern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and parts of Tajikistan. Its borders, however, were anything but stable, shifting often as imperial priorities changed.

The Turkestan Governor-Generalship on a map of the Russian Empire / Wikimedia Commons

For instance, the region of Jetisu (Semirechye) first became part of Turkestan and was then transferred to the Governor-Generalship of the Steppei

In addition, its population was exceptionally diverse. Russians made up a relatively small minority; around the turn of the twentieth century, there were roughly ten times more indigenous Central Asian inhabitants than Russian settlers, an imbalance that shaped nearly every aspect of life in Turkestan.

Orthodoxy in Turkestan: What Did It Look Like?

The Orthodox Church in Turkestan was not a single, uniform entity, but a highly complex, layered institution. On the one hand was the formal church structure with the establishment of the Diocese of Turkestan and Tashkent in 1871, complete with a bishop for the region and the higher administrative bodies of the Orthodox Church. On the other hand were the settlers who moved to Turkestan from across the Russian Empire and practiced their everyday religious life, giving rise to a more informal, lived form of Orthodox life in Turkestan.

The colonial administration deliberately encouraged the migration of Orthodox settlers, rather than Protestants or Old Believersi

The Church of St. Nicholas in Kulja, demolished in the 1960s / Wikimedia Commons

When all of these settlers came together in Turkestan, the authorities realized that not everyone understood Orthodoxy in exactly the same way. There were slight variations in practice, which, in some cases, led to conflicts among the settlers themselves. Moreover, many Old Believers, whom Church authorities labeled ‘schismatics’, also arrived in the region, further complicating the diocesan administration’s efforts to maintain cohesion among Orthodox Christians.

Coexisting Faiths: Islam and Orthodoxy

What set Central Asia apart from earlier imperial expansions is that it became part of the Russian Empire relatively late. Throughout the history of the Russian Empire, the Church had functioned as one of the central symbols of the tsar’s authority, reinforcing political control through religious presence. In many conquered territories, the Church was granted a relatively privileged position: it was protected by the state and allowed to establish itself institutionally, including through access to property and land.

By the time the Russian Empire expanded into Central Asia, however, the imperial project had begun to diverge from the Church’s missionary ambitions. Some officials in the Russian government worried about antagonizing the large Muslim population they sought to govern. As a result, the Orthodox Church was not permitted to engage in extensive missionary activity in the region.

In fact, when the Most Holy Governing Synod* [Tooltip: The Most Holy Governing Synod was the state-controlled administrative body that replaced the Patriarchate as the head of the Russian Orthodox Church from 1721 until 1917, under the direct authority of the tsar.] informed Turkestan’s first Governor-General Konstantin von Kaufmann that it intended to establish a Diocese of Tashkent and Turkestan with its seat in Tashkent, he flatly refused to endorse the plan. Although Tashkent was the administrative capital of Turkestan, von Kaufmann’s response was unambiguous: he did not want an Orthodox bishop based in the province’s main city. Instead, he urged the Church to locate the diocese in Semirechye, in Verny (Almaty), where the Russian population was larger and where there were fewer prominent centers of Islam.

Konstantin von Kaufman, 1873 / Wikimedia Commons

In that setting, an expanded Orthodox presence was, in his view, less likely to provoke offence. As a result, the diocesan ‘capital’ of Turkestan and Tashkent was, for a long period, effectively Verny rather than Tashkent, a situation that lasted until 1916. Thus, a degree of mistrust and tension developed between the Orthodox Church and the colonial authorities of Turkestan.

Mazars and Orthodox Holy Sites

Were there interactions between Muslim and Orthodox holy sites? Yes, of course. Kazakhstan, as well as Central Asia more broadly, has a fascinating history of diverse religious traditions, with Islam as the dominant faith and various sacred sites scattered across the landscape. And for decades, the interaction of these different religions and holy places unfolded in complex ways, involving both conflict and cooperation.

Qur’an reading. Turkestan Album, 1872 / Library of Congress

The colonial authorities were concerned about provoking conflict and mistrust. At the same time, some members of the administration actively promoted the establishment of Orthodox holy places as a way to entrench Russian identity in certain parts of the empire. The logic was straightforward: if a monastery was founded in one place and if a shrine was established in another, then, in the eyes of what we might call Orthodox Russian traditionalists, territory was not merely governed but being symbolically claimed, making it part of the imperial Russian realm. This ambition created points of tension within the broader imperial project, yet it could also align with administrative aims under certain conditions, producing moments of cooperation alongside conflict.

In my research, I have come across numerous examples of reciprocal hospitality between Orthodox Christians and Muslims. Part of the reason lies in the sheer scale of the territory. Orthodox communities were often scattered far from one another, and the Church struggled to provide all of them with enough clergy for their spiritual and religious needs. Priests, therefore, moved between settlements and parishes, traveling long distances, often on horseback, across the steppe to reach one community after another.

Constantine and Helena Cathedral, Astana / Wikimedia Commons

In many cases, these journeys depended on help from local nomadic groups, and priests would find shelter with them during their journeys. In a number of cases, Muslim merchants even contributed to the construction of churches. They did so partly as a way to signal loyalty to the authorities and partly as a practical strategy to reduce the risk of conflict.

One example I found in the archives comes from outside Turkestan proper, in the Steppe Governor-Generalship, in what is now Astana (then Akmolinsk). The city’s oldest church, the Cathedral of Saints Constantine and Helen, was built in part by a Muslim carpenter. It is a small detail, but a revealing one: it points to a lived religious landscape in which boundaries could harden into conflict, yet could also be crossed through everyday forms of cooperation. In that sense, the short answer is that the relationship between the Muslim and Orthodox communities contained both tension and collaboration.

What About Religious Conversion?

There were certainly cases of religious conversion, and this took place for different reasons. In many instances, however, conversion occurred precisely at the point at which tensions flared. When officials learned that a local Central Asian resident—whether Kazakh, Sart, Kyrgyz, or from another community—had converted to Orthodoxy, the local Muslim community often reacted defensively. The colonial administration viewed this as a fairly dangerous flashpoint as conversion could easily become a catalyst for wider conflict. This is one reason the authorities so often pursued policies of separation and restraint.

There were also cases moving in the other direction, with Orthodox settlers converting to Islam. Often, these conversions were tied to marriage: a settler might marry a local woman, or a local man might marry into a settler community, and one spouse would adopt the other’s faith as part of forming a household.

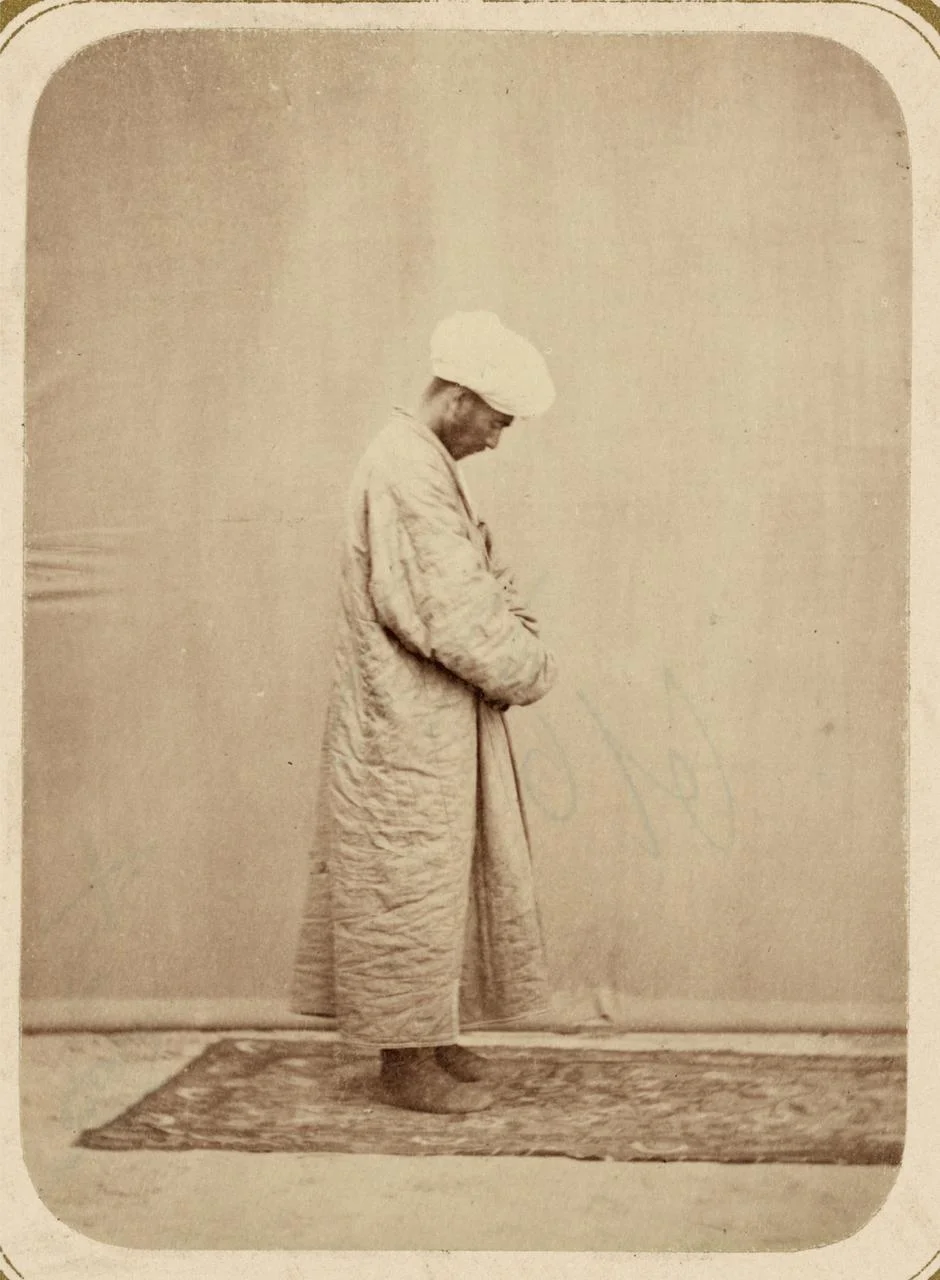

Prayer time. Turkestan Album, 1872 / Library of Congress

But not all conversions were familial. I encountered one case in which a settler fell on extremely hard times. He was destitute, unable to secure support from his own community, and was ultimately taken in by the Kazakhs. He then declared, in effect, that he was now Muslim. When stories like this circulated, they could become minor public scandals. Newspapers would portray the episode as alarming and urge action, often drawing an uncomfortable conclusion for the Orthodox establishment: charitable provision needed to be strengthened, because it appeared, in this instance at least, that Muslims were caring for the poor more effectively than the Church.

This kind of rivalry could be constructive, at least in one sense: it encouraged communities to ‘outdo’ one another in acts of charity, providing assistance more generously, more visibly and more consistently to those in need. Yet the same dynamic also carried obvious risks. When religious competition was understood as a struggle over loyalty, identity, and authority, it could quickly become volatile and, under the wrong conditions, tip into violent conflict.