This is perhaps the biggest dead end in historical scholarship. No one has ever explained what a Roman dodecahedron is and why the Romans carried it around with them everywhere. After reading this article, maybe you can figure it out!

The word ‘dodecahedron’ was invented by archeologists. After all, something had to be written in excavation site catalogs and museum collections. In stereometry, a twelve-sided box is known as a dodecahedron; in fact, the word itself means ‘twelve faces’ in ancient Greek.

A Roman dodecahedron is a small (measuring about 4–10 centimeters) twelve-sided object with pentagonal faces. The tops of the object are equipped with small spheres, and in the center of each face is a hole often surrounded by a pattern of circles. These holes may vary in size.

Bronze or copper dodecahedrons (and a few stone dodecahedrons have also been found) are found wherever there have been Roman settlements—Italy, northern Europe, Asia Minor, and the British Isles. They have been unearthed in the sites of dwellings, tombs, and Roman treasures. Archeologists have found no less than 150 dodecahedrons, all dating from the second and third centuries CE.

What did the Romans do with these objects? Why did they keep them in their homes and take them to the grave? Nobody has the slightest idea. There is not a single mention of dodecahedrons in any written sources that have been found so far. However, they have many possible functions, and each has its own disadvantages.

Bronze dodecahedron with in each plane a hole of different sizes and knobs at the intersections/Alamy

They could be dice for playing or divination. The cons of this are that such dice are very difficult to use. The balls on top prevent them from rolling, and the different weight of each face allows you to control results of throws. In addition, many dodecahedrons are too big to be dice.

These objects could also be candlesticks, and the different widths of the holes make it possible to use candles of different diameters. However, it does beg the question of why the Romans would mass produce candlesticks in such a complex shape and using expensive material. This is especially relevant as the Romans from the lower classes simply used pots and cups for this purpose, and the wealthy preferred much more aesthetically pleasing and expensive compositions. In addition, only one dodecahedron with any traces of wax has been found, and even that most likely remained after the process of casting.

The dodecahedron could have been a device for knitting gloves of different sizes, and some clever people have been able to demonstrate what this process might have looked like. The disadvantages of this are that some holes in the dodecahedrons are so small that not even a rat’s tail, let alone a finger, could squeeze through. Also, it is much easier to knit gloves (which the Romans were not big fans of) with regular needles.

The Netherlands Roman period, dodecahedron, hexagon, metal, bronze, height, 7.5 cm, roman 1-300 AD, the Netherlands, Gelderland, Overbetuwe, Elst - I/Alamy

It could also have been a rangefinder, a device for measuring the distance to an object. The cons of this function are that any object, even a pencil, can be used to measure distance—it's all about exact proportions and standardized marks. There are no standards for dodecahedrons, and they are all different with different sizes, patterns, et cetera. Consequently, they are completely unsuitable as a measuring device.

This object could also have been used as a solar calendar, which allows you to calculate the time of spring and winter sowing based on the angles of the rays of the sun. The cons of this are that the calculations are too complicated for plowmen. It was much easier to ask the neighbors what day of the month it was—after all, the Romans had no problems using calendars.

The dodecahedron may have been some kind of sacred object for magical and ritual practices that we know nothing about. However, this doesn’t make things any clearer for us to understand about how it may have been used.

It could have been a child’s toy to improve finger dexterity or a kind of decoration for a wagon, among other possibilities. However, its disadvantages are clear: you might as well say it was a weight the Romans put on top of a barrel to hold it shut. This is too complicated a thing for such a vague purpose.

So, the question of the purpose of dodecahedrons remains open. Until now, people have not been able to solve this mystery, and thus, they distract themselves with more tangible pursuits. For example, they erect monuments to Roman dodecahedrons, of which there are currently at least three—one in Belgium and two in Germany.

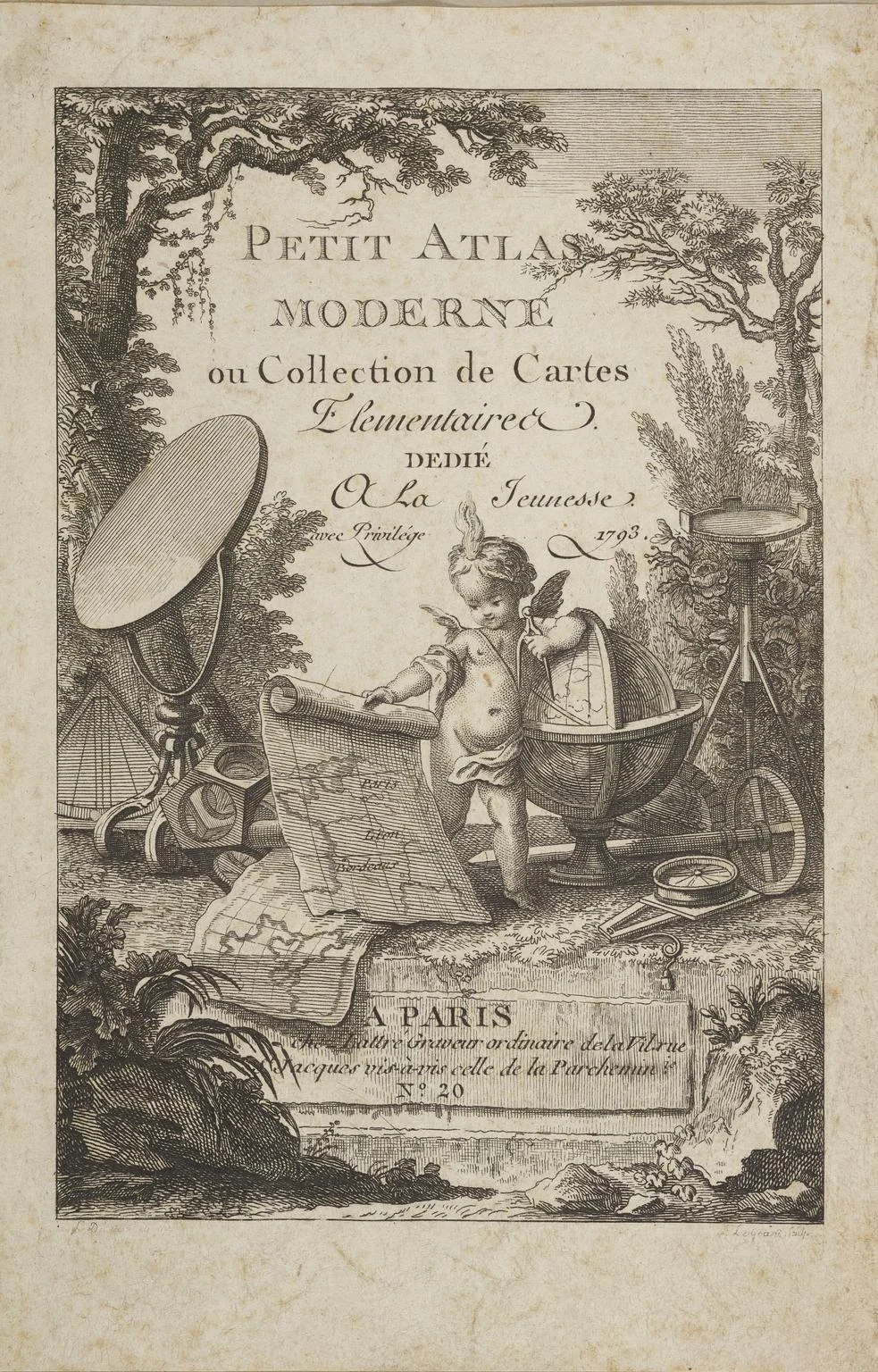

The recently discovered cover of the atlas Petit Atlas Moderne, published in 1799, added some fuel to the fire of discussion. Among the geodetic devices on the engraving, we can clearly recognize the dodecahedron. Where did it come from, and did the people of 1799 know something about dodecahedrons that we do not?

Trade card for Lattre, cartographer, France, 1792/Getty images