Between the 1930s and mid-1940s, the Soviet government carried out mass deportations of various ethnic groups to Kazakhstan in several waves. A significant portion of those deported were women and children, and many of them never made it to their place of exile. Those who survived faced a reality for which no preparation was possible—or even imaginable. In this article, historian Zauresh Saktaganova examines how women endured forced relocations and the reasons why many remained silent about their experiences until decades later.

The Various Types of Relocation

The deportation processes in the Soviet Union became a serious subject of study for researchers and society only in the 1990s. Deportations in the USSR were carried out on two main grounds: social and ethnic. Social deportations targeted ‘socially dangerous elements’, who according to the authorities included communities like the Cossacks, kulaks, et cetera. Ethnic deportations, on the other hand, affected entire peoples who were labeled ‘politically unreliable’ by the Bolsheviks. In the end, a total of fifty-two deportation campaigns were carried out in the USSR, affecting millions of people. More than half of them were deported based on ethnicityi

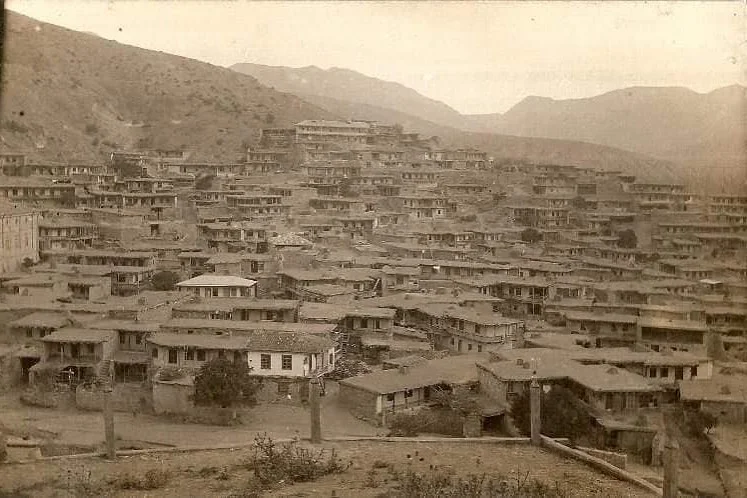

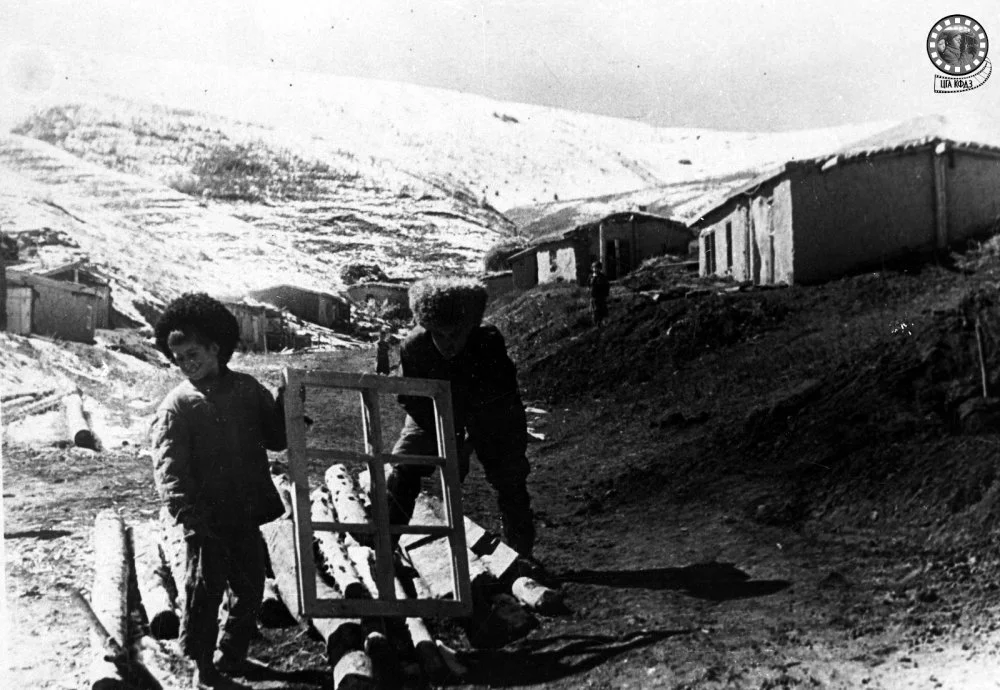

Deported Chechens during housing construction. Tekeli / CSACPA

Memories of the deportations began to appear publicly on a large scale in the late 1980s, and at first, they were primarily shared by men. This is partly because women in the post-Soviet regions were more accustomed to staying silent about their traumatic experiencesi

A Shared Language of Trauma

Many women’s stories about deportation share the same patterns, which are not always said directly but are recognizable through tone, word choice, and the very structure of the narrative.

Crimea. Deserted village of Uskut after the deportation of the Crimean Tatars. New residents had not yet arrived. 1945 / Wikimedia Commons

First, almost all recollections begin the same way, with impersonal verbs: ‘It was announced we were to be relocated’, ‘We were given three days to pack’, ‘We were allowed to take’, et cetera. Even though it is now very clear who was personally responsible for these deportations, the women who lived through them still speak of the events in an impersonal way, suggesting how deeply the experience of deportation was marked by powerlessness.

Second, another recurring theme is the complete lack of privacy, even for basic hygiene. For women, this subject is always painful, yet they still speak of it: ‘Of course, there were no facilities—just a bucket in the corner for our needs.’ The third theme is dehumanization. In their recollections, women often describe how they, the deported, were not treated as human beings, using language like ‘cattle wagons’, ‘inhuman conditions’, ‘herded like livestock’, ‘treated like animals’ to describe their experiences. These characteristics appear, in one form or another, in many testimonies.

Deported Chechens during housing construction. Tekeli / CSACPA

May 1936: The Deportation of Poles

Following the failed attempt to establish a Soviet regime in Poland, relations between the USSR and Poland began deteriorating as early as the 1920s. The first wave of forced relocations took place in 1929–30 and primarily affected Polish communists living in the Soviet Union. The subsequent two waves of deportations—first in 1936 and again in 1940–41—were connected to rising tensions with Germany and the onset of war. The Poles were relocated from the territories of Western Belarus and Ukraine to regions of the Kazakh SSR and Siberia.

Mother of Stanilav Kulakowski / Ałmatyński Kurier Polonijny | No. 2(13), 2016 / Ałmatyński Kurier Polonijny, Polish Cultural Centre "Więź" / https://wienz.kz

Stanislav Kulakovsky’s mother was deported from Ukraine in May 1936 along with her older brother’s family. In Ukraine, she had a fiancé who, one evening, was taken away by a ‘black raven’ (a term commonly used for NKVDi

They announced the relocation and gave us three days to prepare. We were allowed to take everything with us: cows, chickens, goats, horses. After three days, wagons arrived and took us to the train station, escorted by mounted police. In the morning, we arrived at the station and were loaded immediately. On the tracks, there were cattle cars with sliding doors and four narrow windows at the top. They loaded ten to fifteen families into each car. Only bedding was allowed inside the wagon; all other belongings were stacked at the end of the train.

The train arrived at the Tainsha Station in northern Kazakhstan in early June. And according to Stanislav Kulakovsky’s mother, from there, the deportees were taken 20 kilometers into the steppe:

They drove us along a steppe road, with feather grass all around, skylarks in the sky, entire meadows of wild strawberries—no trees, no shade, no buildings. We were unloaded in a bare, uninhabited, endless steppe near a single well, where only stakes had been driven into the ground. We were given three days to settle in. Tents were set up, but almost immediately, the deportees began building dugoutsi

Except for nursing mothers, everyone was expected to work. Their task was to build housing, a school, a hospital, and a barn for livestock. They built using adobei

Mother remembered that in the first few months, many people died, especially children. They buried their loved ones out in the steppe, unable to even put up a cross as there was nothing to make one from. There was a Kazakh auli

The deported Poles were classified as ‘special settlers’—people who had been forcibly relocated from their homes. This was a specific category of repressed individuals in the USSR who, until 1944, were overseen by the Department of Correctional Labor Colonies (abbreviated as OITK) of the NKVD. Special settlers were required to live in isolated, restricted settlements and were forbidden to leave them without special permission. To stay under surveillance, they had to report regularly to the commandant’s office. Speaking about their interactions with the locals, Stanislav Kulakovsky’s mother said:

The local people didn’t mistreat the settlers—on the contrary, they tried to help however they could. They were friendly. The boys, once they got to know kids from the aul, became friends and kept in touch.

During the USSR’s involvement in the Second World War (1941–45), a military tax was added to income and agricultural taxes. The Kulakovsky family had three children, and the father had been conscripted into a labor army. They had only one cow—their sole source of sustenance. They had no means to pay the required tax. Stanislav Kulakovsky remembered:

Once again, Mother was summoned to the local official's office, who suggested coming to see how she lived. They urged her to sell the cow and pay the tax. After seeing their situation, he said: ‘I never expected this—I couldn’t have imagined. Mother, if you sell the cow, you’ll lose your children; keep the cow, and you’ll save them.’ Then he left.

Soon, Kulakovsky’s mother began making cheese and butter to sell in Taincha or to passengers on trains passing through. Leaving the children behind, she would walk 20 kilometers through the night to reach the train and then return—all to earn money to pay the taxes. On one of these trips, after selling some butter, she was on her way home when the police stopped her. They asked her name, and upon hearing that her name was Kulakovskaya, they assumed she was from a kulak family. They began to question where she had gone and why, with the interrogation dragging on for a long time. Kulakovsky recalls:

Mother came home when the neighbors had already gone to work—she had asked them to keep an eye on the children. The older two were fine, but the youngest was lying there, whimpering. But nothing helped, and he died. Mother cried bitterly, blaming herself. The last time I heard this memory was in late November 1980. On 7 December 1980, my mother passed away. And so, she left this world carrying that pain.

September 1941: The Deportation of the Germans

Germans had been living in the Volga region since the reign of Catherine II, and after the 1917 Revolution, they were granted their own autonomous republic called the Volga German ASSR. In 1941, once war broke out between the USSR and Nazi Germany, they were declared an unreliable population, and at the end of September, once the grain harvest in the Volga region was complete, the forced resettlement of Germans began. Around half a million Germans were deported to Siberia and Kazakhstan.

Irma Fittel, a resident of the village of Telmanskoye in the Karaganda region, recollected:

We were expelled on 23 September 1941 from the village of Olgino in the Zaporizhzhia region. We were told to pack within twenty-four hours and prepare to leave. We were allowed to take only a week’s supply of food, warm clothes, and bedding and nothing else. There were four of us in our family at the time: my mother, me, and two brothers. My father had been accused of espionage and executed in 1938. All the men in our family had already been sent to forced labor earlier, so it was just women and children who were deported. After twenty-four hours, we were taken to the station and from there to the port in Berdyansk.

The deportation itself was terrifying—I saw loved ones dying. I remember my brother died on the way to Kazakhstan; he had an infection. The orderlies came and took him, and my mother said he was never buried. She mourned for a long time, saying his bones were left in the cold in a foreign land. And there were many such cases. My aunt’s infant died—her milk dried up, and she had nothing to feed him with. It was a terrible time. We were transported in inhumane conditions, herded like cattle into filthy train decks.

Two weeks later, the train carrying Irma Fittel arrived in the city of Yeysk in the Krasnodar region. A couple of days later, it was announced that they would have to head back to the railway station again. Talking of that day, Fittel said:

We were taken in a freight car to an unknown destination. Of course, there were no decent conditions—just a barrel in the corner for our ‘basic’ needs. We sat on top of each other, our legs quickly went numb, and it was impossible to stand. The train would stop about once every two days, and we were allowed outside briefly to drink some water. Bread was given out only on rare occasions. When we arrived in Kazakhstan, it was already very cold—it was November—and the clothes we had brought with us were not suited to the season. We were initially taken to northern Kazakhstan, to the Akmola region. Two weeks later, we were relocated to the Karaganda region. We were brought by truck to ‘Point 22’.

The arriving Germans were housed in dugouts alongside other special settlers who were already living in the area. Irma Fittel’s family was placed with an elderly couple in a one-room dugout with a stove in the center, where she described the living conditions in this way:

There were six of us living in one room. The dugouts that the special settlers lived in were made of adobe. Since the space was small, the homes stayed warm. We had to get food by trading our clothing and what we had brought from home, for dung fuel from the local people. Our diet was very poor: at first, we survived on the supplies we had brought. My mother was very skilled at sewing and knitting, and she received milk and potatoes in exchange for her work. That’s how we managed to get by.

The village Irma Fittel and her family ended up in was impoverished, and even the local residents were on the brink of survival. Speaking of those terrible times, she said:

The hosts we lived with were very kind people and tried to help us in every way. They always sat us at the table. Mostly, we ate dumplings. I remember once my brother and I caught a hare—we were so happy. In the summer, we started fishing and later moved to another state farm, where we planted a vegetable garden. But that first winter, we were swollen from hunger. I still remember the pain in my stomach. Sometimes, we didn’t eat for two or three days. We drank only melted snow. There wasn’t even water in the village. We would go into the fields, dig through the snow, and find some roots or grass to make soup from. I don’t know how we survived that winter. In the spring, we started working at the cattle yards. Life under those conditions was unbearable—there was nothing, not even a way to wash ourselves. Everyone got lice during the journey. Our faces broke out in rashes from the filth. In the cold, hungry steppe, we searched desperately for anything, a twig, a stick, to light the stove.

In the first year after the family was relocated to Kazakhstan, Fittel’s brother fell ill. There were no medicines to bring down his high fever. Irma’s mother tried to give him tea made from branches they had managed to collect in the steppe, but it didn’t help. Soon, the child died.

Irma’s aunt found out that conditions in the sixth settlement of the Osakarovsky district were better than where they were living at the time. However, to leave the boundaries of the collective farm, they not only had to get permission but also had to pay a tax. And so, using the little money they had left, they paid this wartime tax and moved to the sixth settlement. Not far from the village was a small patch of forest land where they could gather firewood. This settlement was more prosperous and inhabited by Ukrainian special settlers. They had houses with roofs and large windows. A river flowed close by, where it was possible to catch fish. Fittel was almost fifteen then, considered grown-up, and watched over all the little ones. Eventually, we moved to the Karaganda region and stayed there.

Despite the help of and support from the Kazakh locals, life remained grim. Everyone in Irma Fittel’s family, children included, had to work twelve to fifteen hours a day just to survive. All the clothes they brought wore out very quickly. She recalled:

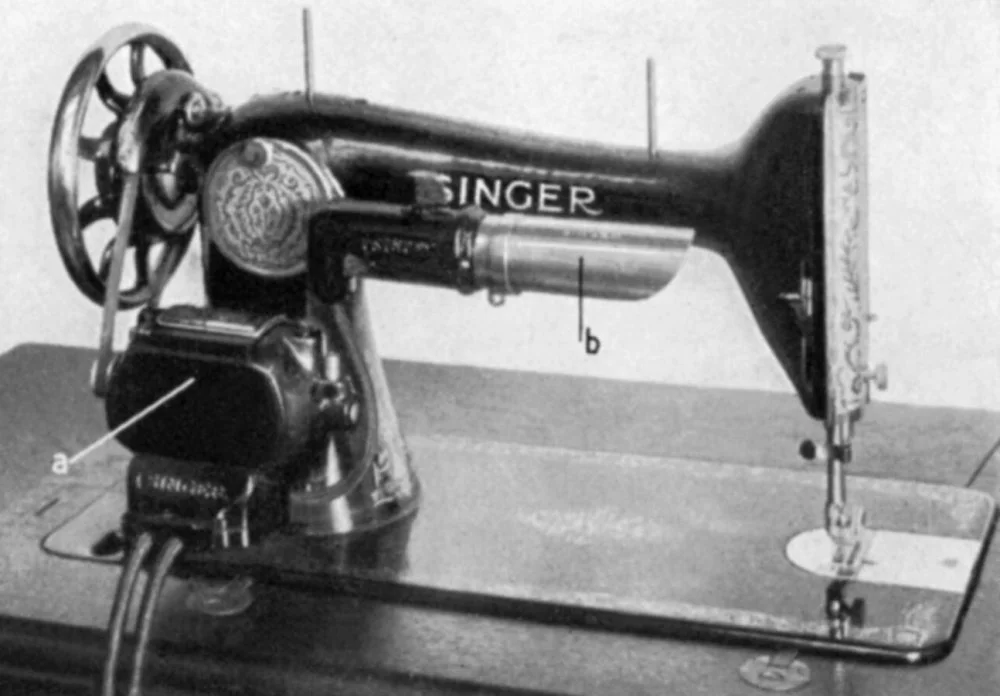

We also brought a sewing machine with us, which helped us survive. My mother was an excellent seamstress: she made headscarves out of bed sheets, embroidered them, and exchanged them for food. In the second year after we were deported, we started knitting socks, mittens, and hats from wool, and that’s how we managed to get by. Every scrap of fabric was worth its weight in gold. The elderly couple we lived with in the first year gave us a warm padded jacket and just one pair of felt boots for the whole family. So we took turns wearing them.

Irma’s younger brother was able to attend school in the settlement they lived in, graduate, and then enroll in a driving school. Irma, who was fifteen by then, did not continue her studies but helped her mother with household chores and worked.

February 1944: The Deportation of Ingush and Chechens

The forced removal of citizens from the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) began on 23 February 1944 and lasted until March 9. Around half a million people were relocated to the Kazakh and Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republics (SSRs) and partially to the Uzbek and Tajik SSRs (estimates vary). The Chechen-Ingush ASSR itself was abolished.

Ashat Ilyasovna Mazieva, who was born in 1931 and was thirteen years old at the time of the deportation, shared her memories of the time, saying:

We lived in the village of Ekazhevo in the Chechen-Ingush ASSR. At the end of 1943, NKVD agents began arriving in our village, and soldiers were walking around in uniform. There was a rumor going around the village that a deportation of the Ingush people was being readied. Although everyone knew well that in 1943 the Karachays had been deported, everyone still hoped for the best and thought that our people would not suffer the same fate. But then 23 February came.

On that day, Ashat Mazieva’s father was pulled out of the house half-dressed and taken away. Some time later, the family was told that he had been executed. But the family’s ordeal was far from over, and soon, they too were torn from their home:

They told us to prepare, that we had twenty-four hours to pack. We started crying. My mother asked where we were going. She was given an answer very rudely and shoved. They said we were going to die of hunger—if we even made it that far. We hurried to pack our things. We took a sack of corn, flour, potatoes, and some other things that I don’t remember exactly now. We put on as many clothes as possible. My older sister helped my mother gather the younger ones; they were all whining. The next day, they came for us. Nobody resisted: everyone was afraid they would be killed. Mom told us to behave like mice. That’s how, at thirteen, I became an ‘enemy of the people’.

At the time of the relocation, Ashat Mazieva’s family consisted of seven people: her mother, Zulfia, and six children, including Ashat. The youngest child was just three months old, born at the end of 1943:

He was named Gasar, and he died on the road from hunger. I remember how my mother cried. The guards came, searched the train car, and threw him out by the roadside. That wasn’t uncommon then; they treated us like animals. For our people, it is shameful not to bury the bodies of the dead, but circumstances forced us to accept this fate.

The deportees, including Ashat Mazieva’s family, were brought to the Karaganda region, to the village of Zarechnoye. She described their experience as:

The locals received us well, and thanks to them, we survived. Everyone was willing to share a piece of bread. They themselves didn’t live very well—they were actually worse off that we were in our homeland. The local population lived in dugouts. The first winter, the locals took us into their homes, and by summer, we were already building our own houses. We were all sent to work on the collective farm, keeping records of our work days. We weren’t paid—they gave us bread, some kind of watery soup, and that was all. In spring, they felt sorry for us and gave us a cow and two rams. That’s what we lived on. We milked the cow. We started planting a garden. But we had no means of subsistence. We ended up in an empty steppe. If it weren’t for the locals taking us in, we all would have died.

However, their struggle for survival was far from finished. A little later, typhus spread throughout the entire steppe. There was no medicine, and whole families died. Ashat Mazieva later described the horror of those days:

I remember, every day we were sent out to various jobs, and one day an Ingush family didn’t come out to work: it turned out they had all died. They simply froze to death. People were dying like flies. And we couldn’t bury them—there were no shovels or crowbars. In winter, we buried them in the snow, and some were eaten by wolves. We washed our clothes and ourselves using ash and sand. There was nothing else. We had long hair, and everyone got lice. I remember how itchy my head was.

To make matters worse, the shoes the deportees brought from Ingushetia were not suitable for the season and wore out quickly. There was no money to buy shoes, so they had to make their own chuni (traditional footwear). The process was grueling: first, they took some cowhide from a cow’s leg and dried it. Then, they put their feet inside and punched holes around it, which they tied with cord or wire. Instead of insoles or padding, they used straw and wore these shoes for several seasons. Some resorted to simply wrapped a piece of hide around the foot and tied it in front with a rope. When the first wool appeared after shearing the sheep, the women began knitting socks, making insoles and felting cloth. They used sheep skins to make various headwear and clothing to keep warm in any way they could.

The Gazdiev family of Ingush origin beside their deceased daughter. Kazakhstan, 1944 / Wikimedia Commons

And even as they fought for survival, life, in some small way, went on. Ashat Mazieva, along with other children who had been relocated, was sent to school. Since she didn’t know Russian, she was placed in first grade even though she was already a teenager.

Many laughed at me. But the teachers were good. Everyone understood what was being taught. Time passed, and we gradually began to learn Russian. At home, we only spoke our native language. Even on foreign soil, we continued to honor our religious traditions—we read namaz and observed the fast of Uraza. However, these practices were strictly punishable, and if they had found out, we could have been imprisoned.

The Deportation of Other Peoples and an Epilogue

These fragments of women’s memories of deportation reveal some patterns. The first is the seeming normality with which the women spoke about death, including of their loved ones. This matter-of-factness, the acknowledgment of many deaths, is not a sign of callousness but of acceptance of the inevitable and of coming to terms with it. The deported women could not have survived—or, indeed, saved their children and families—if they had not ‘hardened’, if they had not ‘grown used’ to death.

Soviet deportees boarding a train for their destinations in the Gulags of Siberia. It could depict any of the mass deportations carried out under Stalin's rule. 1940 / Alamy

The second pattern is related to memories of gratitude, which are especially characteristic of the people deported specifically to Kazakhstan. Women, regardless of nationality or age (whether they were adults or children at the time of deportation), speak with great gratitude about their relationships with Kazakhs and Kazakhstani people (citizens or inhabitants of Kazakhstan of a different ethnic background from ethnic Kazakhs) in general. Kazakhstan became a second homeland for many people who suffered Stalinist repressions, including Koreans, Kurds, Armenians, Turks, Iranians, and other groups considered ‘undesirable’ by the Soviet system.

Singer sewing machine. 1920s / Alamy

The harsh and wild steppe did not judge these people in any way. Instead, it was a place where they survived because of their collective resilience and quiet strength. These memories of gratitude, passed down through generations, remind us that even in the darkest chapters of history, humanity persists in the acts of ordinary people who chose to stand rather than turn away.

Note from the author: This article draws on the recollections of deported women, recorded over the years by journalists in newspapers and gathered through interviews conducted as part of the Karaganda University research project called The Great Patriotic War and the Women of Kazakhstan at the Front and Home Front: Women’s Stories and Everyday Life.

What to read

-

Депортированные в Казахстан народы: время и судьбы. — Алматы: Арыс-Казахстан, 1998. 428 с.

-

Из истории депортаций. Казахстан. 1935–1939 гг. Сборник документов. — Алматы: LEM, 2014. 740 с.

-

Интервью с Мазиевой Ашат Ильясовной, 1931 г.р., жительницей Карагандинской области, записано Майлыбаевой Д. в 2019 г.

-

Интервью с Фиттель Ирмой, 1927 г.р., жительницей Карагандинской области, записано Майлыбаевой Д. в 2019 г.

-

Земсков В.Н. Спецпоселенцы в СССР, 1930–1960. — М.: Наука, 2005. 306 с.

-

Сталинские депортации. 1928–1953. Под общей редакцией академика А.Н. Яковлева. Составитель Н.Л. Поболь, П.М. Полян. Серия: Россия. XX век. Документы. — М.: МФД, Материк, 2005. 904 с.

-

Conquest R. Soviet Deportation of Nationalities. — Macmillan, 1960. 203 p.

-

История села Подольское. Ałmatyński Kurier Polonijny | №2(13)•2016)