Reconstruction Of The Ancient Greek Bronze Statues Known As The Riace Warriors (Aka Riace Bronzes), Showing How The Statues May Have Looked With Their Original Polychrome Colouring. On Display At Berlin's Altes Museum/Alamy

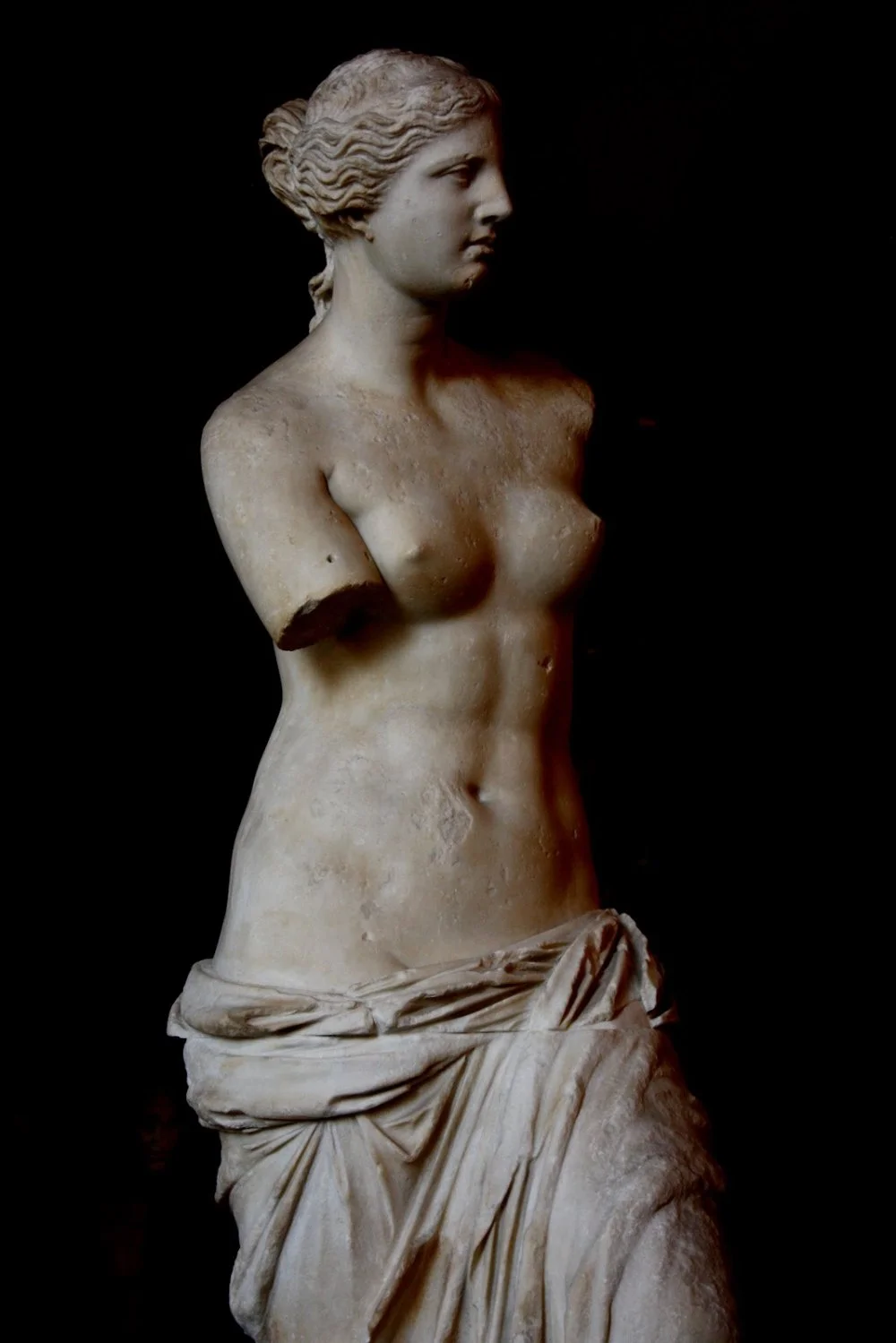

It is a sad truth that even acknowledged masterpieces require promotion and strategic marketing to become truly famous. Take this exceptional paired composition for instance. It could have become as famous as Venus de Milo. But it didn't. And some of that has to do with serendipity.

There is an old Persian tale about three princes from the city of Serendip who had the supernatural ability to find what they were not looking for. This phenomenon, dubbed ‘serendipity’ by British writer and statesman Horace Walpole, has been a pivotal factor in numerous scientific breakthroughs and historical discoveries over the course of history. Many groundbreaking discoveries and inventions—including cellophane, penicillin, X-rays, Viagra, the microwave effect, inkjet printers, and the discovery of the weight loss properties of the drug Ozempic—were stumbled upon during unrelated research or due to unexpected errors. One of the most famous accidents of all time is the discovery of America, which was found while searching for India and initially mistaken for it.

Venus de Milo. Around 130-100 BC. Louvre, Paris/Wikimedia Commons

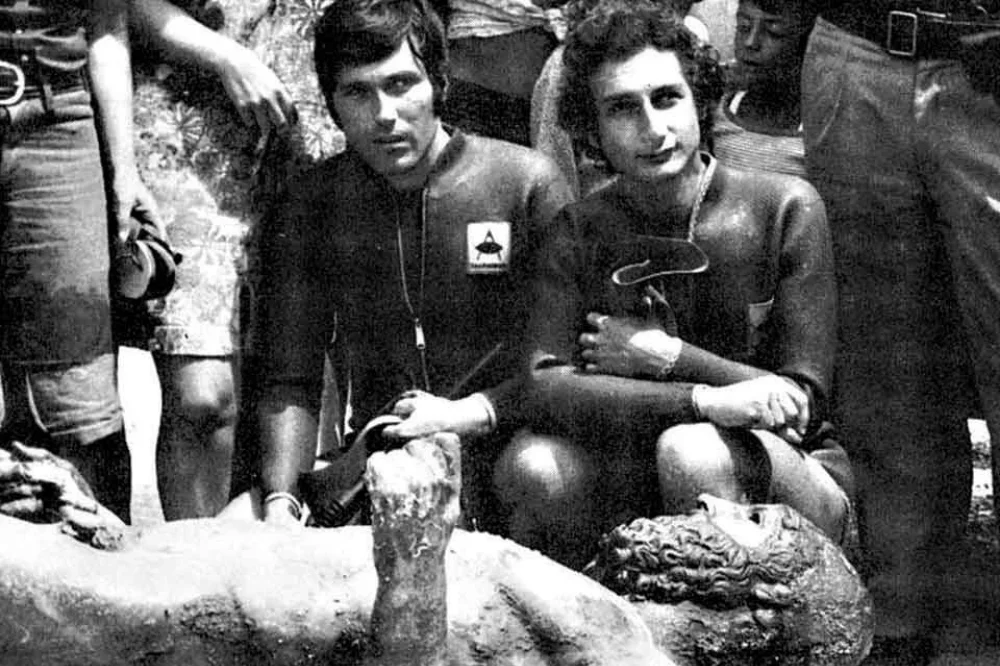

In this same category of serendipitous discoveries is the find by Stefano Mariottini, a pharmacist from Rome. He had no connection to archeology, art, or history, but he loved fishing. Every summer, Mariottini would go to Calabriai

Stefano Mariottini during the raising of sculptures from the sea/From open sources

The two Riace statues are ancient Greek bronze sculptures, which in all likelihood ended up on the seabed due to a shipwreck, though no trace of a wrecked ship was found nearby. They were created in the fifth century BCE, at the peak of classical Greek art. Most researchers believe they belong to different artists and even slightly different periods—there are at least several decades between them. They were probably being transported from Greece to Italy, perhaps to Rome, to be placed in a villa of some dignitary or even an emperor, such as Nero, who encouraged the plunderous import of Greek art.

Both statues depict warriors standing calmly but not in a relaxed posture; one has a more restrained expression, while the other has a frightened look. The warriors are nude, known as ‘heroic nudity’, as artistic tradition requires. One wears a helmet, and both likely hold a shield and spear, but their weapons have been lost. Their height is almost human but slightly exaggerated (about two meters), just enough to create an impression of natural yet extraordinary power. Inside, they are hollow, and the bronze parts from which they are made are cast separately (using a unique technology) and then assembled like construction kit parts. For example, the front parts of their feet were cast separately, and on the feet, the middle toes were cast separately. Their pupils are made of gold paste, lips and nipples of copper, and teeth and eyelashes (eyelashes!) of silver.

Nothing even remotely comparable to the Riace warriors in scale and artistic value has survived since ancient Greek times. There are no monumental bronze statues left—bronze was eagerly recycled, and even Greek marble sculptures are known mostly from Roman copies at best. When the statues were finally restored in 1981—after 2,500 years underwater, they were heavily encrusted with shells—their triumphant tour of the museums of Rome and Florence became a national event, reported on the covers of all magazines.

Riace warriors. Circa 460-450 BC/National Museum in Reggio Calabria/Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images

But this fame proved to be short-lived. The Riace statues are displayed in a separate hall on the basement floor of the National Archaeological Museum of Magna Graecia in the city of Reggio di Calabria. They are, of course, the main attraction not only of the museum but of the entire city, if not the region. Their likenesses adorn posters, T-shirts, and storefront displays, yet beyond Calabria's borders, they remain largely unknown. This lack of recognition might stem from inadequate PR. The English moniker ‘Riace warriors’ at least lends them some mystique, while the Italian term ‘Bronzi di Riace’ (Bronzes of Riace) sounds quite uninteresting. The most problematic part is the name they were given: Statue A and Statue B. Such uninspired labels hardly pave the way to widespread fame.

Murals of Riace Bronzes at Riace train station/Wikimedia Commons

Of course, there is scientific honesty to this nomenclature. No one knows who these figures represent, where they stood, what they were intended for, who created them, or whether they had any relation to each other. However, that has not been the case for all art with unknown origins and purposes. The famous Pompeian fresco depicting a girl with a stylus and writing tablets is called Sappho,1

Fresco of a Woman (Sappho?) Holding Stylus and Tablet. Naples Museum, Italy/Wikimedia Commons

In short, the Riace warriors didn't get lucky with their marketing. Had they been christened with more evocative names, such as Hector and Achilles, their renown might have been significantly greater. In the antechamber of the hall where Statue A and Statue B stand, the history of the discovery is detailed, and the heated debates about the statues' attribution and origin, which historians and archeologists still engage in, are recounted. Mariottini is not even mentioned by name: he is referred to as an ‘amateur diver’. Yet, until recently, he actively participated in the work of the Archaeological Council of Calabria and visited his bronze finds at the museum every year. ‘I still feel the same deep sense of satisfaction and admiration when I look at them,’ he said in an interview.