In July 1963, a deadly mudflow swept down from the Trans-Ili Alatau Mountains of Kazakhstan, destroying Lake Issyk, once a stunning and popular recreation spot. The disaster struck without warning, burying homes and roads under mud and debris. To this day, the exact death toll remains unknown as Soviet newspapers stayed silent on this news for a long time, and no official assessments of the damage were ever released. Exactly ten years later, in July 1973, the capital of the Kazakh SSR, Almaty, faced a similar threat, putting thousands of lives at risk. This time, however, the lessons of the past would not be ignored. This is the story of a nearly forgotten disaster—one that ultimately helped prevent an even greater tragedy.

Mudflows in the Territory of Almaty

Earthquakes have long been a concern for the residents of southern Kazakhstan, though only two major ones have struck present-day Almaty in the past 150 years, one in 1887 and the other in 1910. In contrast, there have been more than 800 mudflows in the past 180 years, and several have had truly catastrophic consequences.

In the nineteenth century, as the Tsarist Russian government built fortifications across Kazakhstan, they also established settlements in locations close to rivers, the lifelines of the steppe. Since most waterways in the region were fed by glaciers, these towns inevitably sprang up in the foothills of the mountains. While the region's seismic activity came as a surprise to the residents of Verny (the Russian name of Almaty then), which was founded in the mid-nineteenth century, the danger of mudflows was still well known.

Locally referred to as ‘floods’, these destructive surges were far more than just water: up to 75 per cent of the moving mass consisted of debris, mud, and rocks.

Faced with this threat, the people of Almaty developed early defenses. They built small dams, known as gabions (metal or woven mesh cages filled with stones), along mountain rivers. These structures allowed water to pass through while holding back mud and large debris. In the 1870s, they created a diversion from the Malaya Almatinka (the Kishi Almaty) River to the Vesnovka (the Esentai), thanks to which the western part of the city gained access to irrigation water and acted as a safety valve. It was now possible to regulate and redirect the flow of the Malaya Almatinka River and drain excess water in the event of a mudflow. It was a crude but effective system, one that would shape how Almaty survived as a city for generationsi

A. Barsukov. Mudflow that hit Lake Issyk. 1963 / CSA CFDA RK

Despite these early efforts, the city could not escape nature’s fury when the Malaya Almatinka River unleashed a devastating mudflow on 8 July 1921. In hours, a catastrophic torrent of debris had impacted approximately 7 per cent of the city’s population. The scale of the devastation was almost unimaginable: 65 homes, 174 outbuildings, 18 mills, a beekeeping station, a tobacco factory, and 2 leather plants were destroyed. An estimated 500 people were killed or went missing, 80 were injured, and 149 bodies were recoveredi

For a city with a population of about 30,000 people, these were enormous losses. For several years afterward, residents suffered from typhoid and cholera due to a severe lack of clean drinking water. Even today, a century later, reminders of that day endure. Along modern-day Dostyq Avenue in Almaty, massive boulders rest near the Kazakhstan Hotel, permanently deposited there by the mudflow.

Kazakhstan’s Own Ritsa

In the mid-twentieth century, there was a serious shortage of places to swim both Almaty and its surroundings. The Qapshaghay Reservoir would not be completed until 1970, and reaching Lake Issyk-Kul meant enduring more than eight hours of a stuffy bus ride through the dusty Kordai Pass. Thus, to offer a summer getaway for the residents of Almaty, in 1958, the Council of Ministers of the Kazakh SSR issued a decree titled ‘On Ensuring Cultural Recreation for Workers at Lake Issyk’.

P. Kudryashev. A group of tourists at Lake Issyk. August 21, 1959 / CSA CFDA RK

Within a year, a recreational park opened at Lake Issyk, complete with a hotel, restaurant, boat station, and dance floor. A wide asphalt highway was laid to the lake, and a bus terminal with a large parking lot was built. On weekends, scheduled buses departed from Almaty every half hour. Photos of the lake were printed on postcards and featured in tourist brochures, which referred to it as the ‘Kazakh Ritsa’i

V. Pozdnenko. At the high-mountain Lake Issyk. 1961 / CSA CFDA RK

Lake Issyk quickly became the primary leisure destination for Almaty residents, especially during the summer heat, drawing thousands of visitors. Although the water was cold and unsuitable for long swims, this didn’t deter anyone. People could rent pedal boats for a ride on the lake or simply sunbathe on the beach. The vacationers seemed blissfully unaware of the disaster in the area in 1921 or that history could repeat itself in the blink of an eye.

7 July 1963

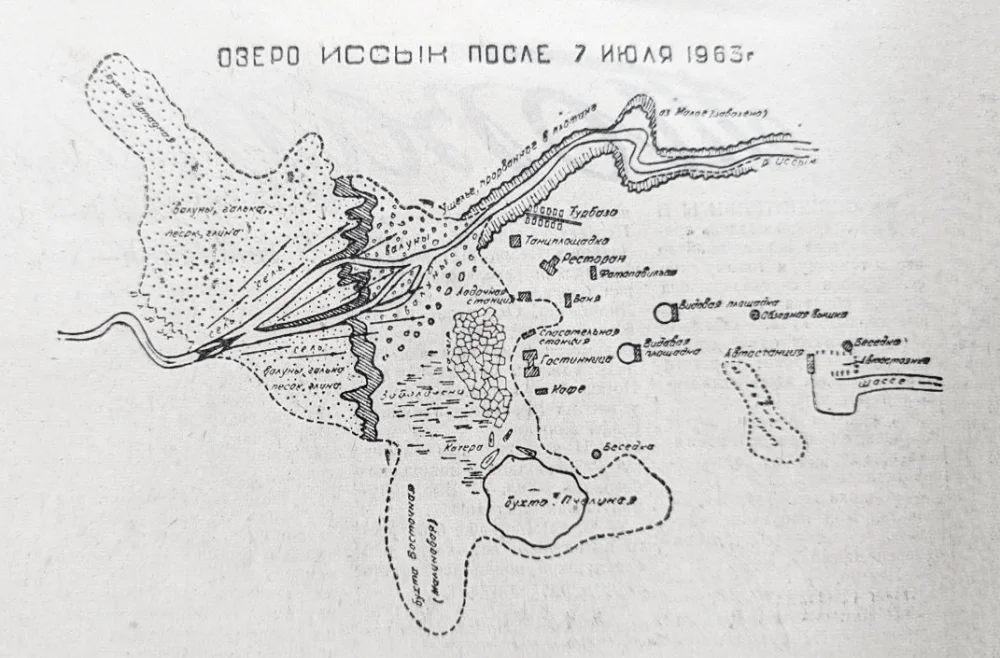

The high-altitude Lake Issyk was formed around 8,000 to 10,000 years ago, when an earthquake triggered a massive landslide. The falling rocks created a natural dam approximately 300 meters high, trapping the waters to form a narrow, deep lake. Initially, the lake was 1,850 meters long, and 500 meters wide, and its depth varied with the seasons—it was about 50 meters in winter, swelling further in the summer due to glacial melt.

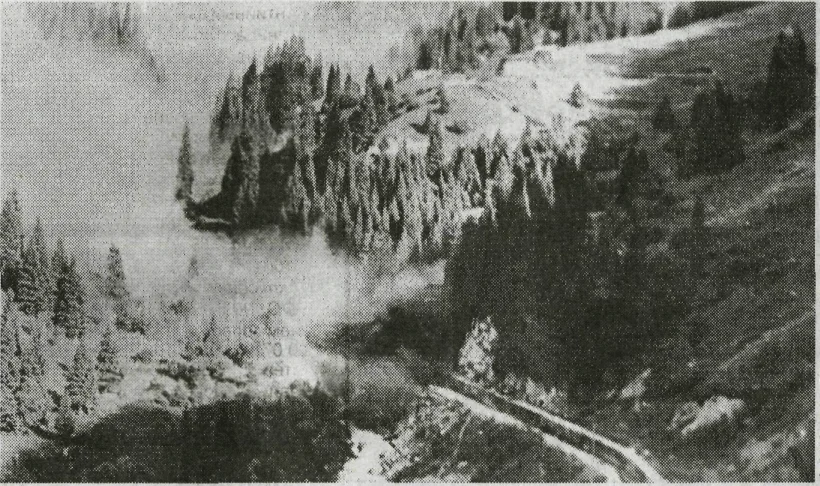

On a hot Sunday in July 1963, the lake was crowded with vacationers; the lake's tranquil surface belied the catastrophe about to unfold. The first wave of the mudflow struck at 2 p.m, and the water in the lake frothed and began to rise with terrifying speed. Twelve successive waves would pound the valley, carrying between 6 and 7 million cubic meters of mud and pulverized rock.

The third wave proved most devastating—where the valley narrowed, its towering wall of debris and water reached staggering heights of 30–40 meters, sweeping away everything in its path with unimaginable forcei

At the time, the director of the Issyk tourist base was Ivan Grigoryevich Aushev. His recollections of the mudflow were first published in the newspaper Trud about a month after the tragedy and later reprinted in Ogni Alatau:

‘To make sure no one was left on the shore,’ Ivan Grigoryevich recalls, ‘we approached the very edge of the river. Carefully maneuvering between the logs, I steered the boat along the delta. When the Western Bay appeared ahead, Nikolai Zavyalov, a mechanic, spotted two people in the water. They were clinging to an overturned boat that had been driven against a snowy cliff. We immediately threw them a rope and helped them climb aboard.

‘Then, we all heard a rapidly growing roar echoing through the gorge, coming straight at us. I turned and saw—just a hundred meters from the river—a black wall of mud and rock surging from behind a sharp bend. It was a terrifying mudflow wave, twelve meters high, thundering through the canyon like an all-consuming avalanche.

‘Everyone on deck rushed into the cabin, and at that moment, the same thought flashed through each of our minds: Will we have time to open the doors when the boat goes underi

And forty years later, in 2003, he gave a detailed interview to the Karavan newspaper, and his testimony is one of the most important firsthand accounts of that tragic day.

Today, sixty-two years after the tragedy, Ivan Aushev is no longer alive, but his memories live on, shared now by Oleg Mikhailovich Aushev, his nephew. On that fateful July day, Oleg’s father and nine-year-old cousin had joined Ivan Aushev, who was on duty, for what should have been a pleasant lakeside outing.

When my uncle [Ivan Aushev] noticed the first signs of the mudflow, he first went around the lake with a megaphone, warning people of the approaching danger. And when rocks began falling into the lake, he used a boat to evacuate people upstream to safer areas where the boat could dock.

As my uncle recalled, being on the lake itself, in the water, wasn’t as terrifying. The real panic began when people started running and driving down the gorge. A bus couldn’t cross the raging stream—there was panic and a stampede.

No one talked much about the dead. Fortunately, none of our relatives perished that day. But even we, as children, understood what a dreadful day it was. My uncle returned with gray hair, even though he had made it through the entire war.

Lives Caught in the Mud

The Soviet media maintained a calculated silence about the disaster. In fact, for the first few weeks, there wasn’t a single word printed about the tragedy itself. Instead, they were filling their pages with international pieces about the oppression of ‘Blacks’ in the US, an American jet crashing into a children’s camp in Pennsylvania (ironically on 7 July, the very same day), the conflict between Cuba and America, military actions in Iraq, Algeria’s independence day, and the fortieth anniversary of the founding of Soviet Buryatia.

Front page of the «Leninshil Zhas» newspaper. July 7, 1963 / National Library of Republic Kazakhstan / Qalam

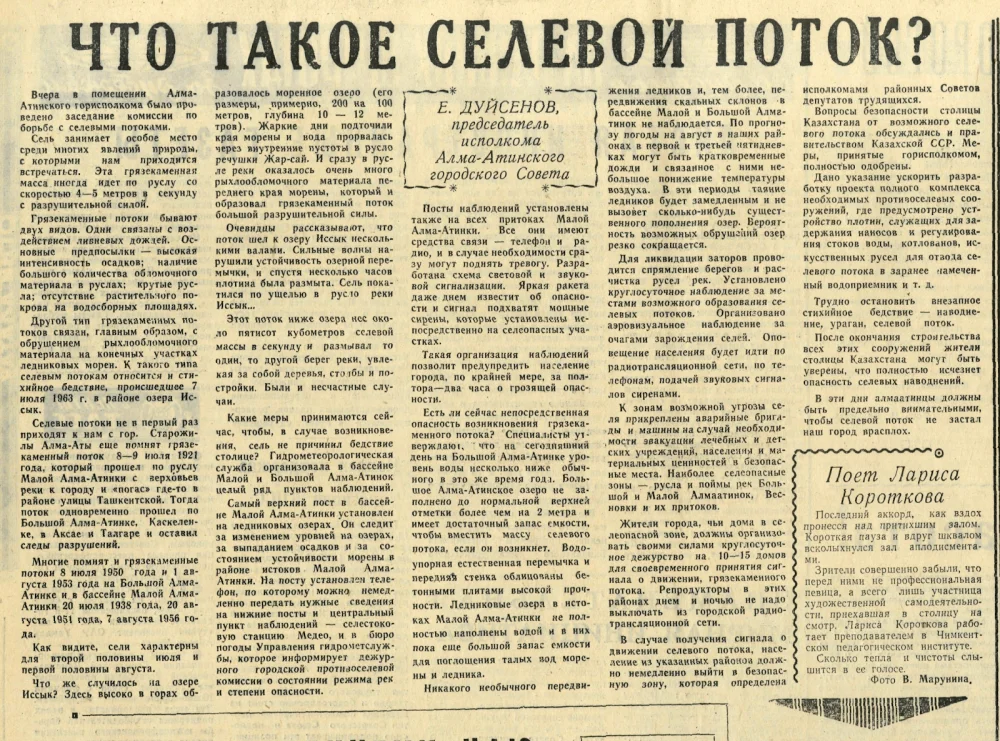

The first article about the incident appeared in the Ogni Alatau newspaper almost twenty days later on 25 July 1963. It was titled ‘What Is a Mudflow?’ and focused on the protective measures being taken to shield Almaty from potential danger. The Issyk tragedy and its victims were mentioned in the article, but only briefly and vaguely to say ‘There were also unfortunate incidents.’

«What is a Mudflow?», «Ogni Alatau» newspaper, July 25, 1963 / National Library of Republic of Kazakhstan / Qalam

To this day, the death toll remains disputed, with estimates ranging wildly from 50 to 2,000 victims. The authorities’ silence wasn’t absolute; rather, it was deliberately ‘selective’. By autumn, several articles had been published about the aftermath of the mudflow. But the newspapers of that time preferred to ‘focus on the positive’. While no publication mentioned the number of victims of the Issyk disaster, Soviet newspapers diligently reported that 2,000 people had been saved.

The bureaucratic response, however, moved with uncharacteristic speed. By August 1963, the Council of Ministers of the Kazakh SSR had already issued a resolution, ‘On Measures to Protect the City of Alma-Ata from Mudflows’, demonstrating that while public acknowledgment might have been almost non-existent, the government recognized the urgent need for preventive action.

The Causes and Consequences of the Issyk Mudflow

Archived meteorological reports indicate that only light rain fell in the mountains on 5 July, and there was no rain at all on 6 July, proving that the mudflow was not caused by a downpour. The Issyk mudflow had a glacial origin—it came from the moraine lake Jarsaii

Along its path, the mudflow destroyed natural barriers, gathering more and more mud and debris. That’s why it reached the lake in successive surges (or waves). In mere hours, successive mudflow waves obliterated the lake, literally displacing all of its waters.

«Following the Mudflow», «Leninskaya Smena» newspaper, September 10, 1963 / National Library of Republic of Kazakhstan

The mass of water, mud, and rocks poured down onto the town of Issyk. Fields that had been planted were seriously damaged, two streets were affected, and several industrial facilities near the river were destroyed, including warehouses of the Issyk winery. The mudflow reached the Kulja Highway, more than 50 kilometers from the lake. As a result of the disaster, the Issyk River changed course.

It was once believed that mudflows only formed in the beds of mountain rivers. However, scientists specializing in mudflow research have now established that destructive flows can form even outside the mountains. Only three factors are required: loose rock debris, water, and a slope.

Twenty years would pass before restoration efforts began at the lake site. A dam and spillway structures were built, but the lake has still not returned to its original size. Nevertheless, the area remains just as beautiful as it was before the mudflow. Today, almost no reminders of the 1963 tragedy exist at the site except for a cross and a Muslim memorial at the site of the former Issyk tourist base.

The Consequences for Almaty

After the 1963 mudflow, it became impossible to ignore the risk of a similar catastrophe occurring in the upper reaches of Almaty. While Issyk had a population of around 21,000, the capital had more than 650,000 residents, meaning that the potential loss of life in the event of a mudflow would be vastly greater. Moreover, the risk of glacial mudflows had significantly increased, in part due to warming temperatures. Glaciologists noted an alarming trend: the volume of the moraine lake near the Tūiyqsu Glacier was rapidly growing. Between 1963 and 1971 alone, it expanded from 76,000 to 250,000 cubic meters, reaching 300,000 by 1973. Soon, the threat of the lake bursting was clear, and it was crucial to begin constructing a dam above Almaty as soon as possible.

A. Barsukov. Mudflow that hit Lake Issyk. 1963 / CSA CFDA RK

Events were hastened not only by the alarming activity of the moraine lake. The fact was that Dinmukhamed Kunaev had personally witnessed the mudflow at Issyk in 1963. On that day, he had brought A. Kosygin, a member of the Presidium of the USSR Council of Ministers, to the lake, and they managed to leave the disaster site shortly before the bridges collapsedi

Unsurprisingly, after the Issyk tragedy, the dam project was launched immediately. However, the abnormal rise in water levels in the mountain lake made it clear that traditional methods, requiring several years of work, would not be fast enough. A mudflow could strike at any moment.

A. Barsukov. Aftermath of the mudflow that hit Lake Issyk. 1963 / CSA CFDA RK

A decision was made to construct the dam employing a controlled explosion. In fact, the idea had first emerged in the mid-1950s, and preparatory work had already begun in the Medeu gorge. But in the late 1950s, the project was frozen, in no small part due to sharp criticism from the scientific community. The idea had many opponents: biologists who warned of the threat to rare species of flora and fauna, and members of a government commission who feared the consequences of a massive explosion just 15 kilometers from Kazakhstan’s largest city. And their concerns were justified. Never before in global history had such a powerful blast been carried out so close to a major cityi

Explosions in the Mountains Near Almaty

In October 1966, the first explosion thundered through Almaty. Residents experienced tremors similar to those of a magnitude 4 earthquake. For safety reasons, people, animals, and valuable property were evacuated in a 9-kilometer radius zone, and the area was cordoned off.

Photo from article «Almaty in the Embrace of the Dragon», «Kazakhstanskaya Pravda» newspaper, July 7, 2006 / National Library of Republic of Kazakhstan / Qalam

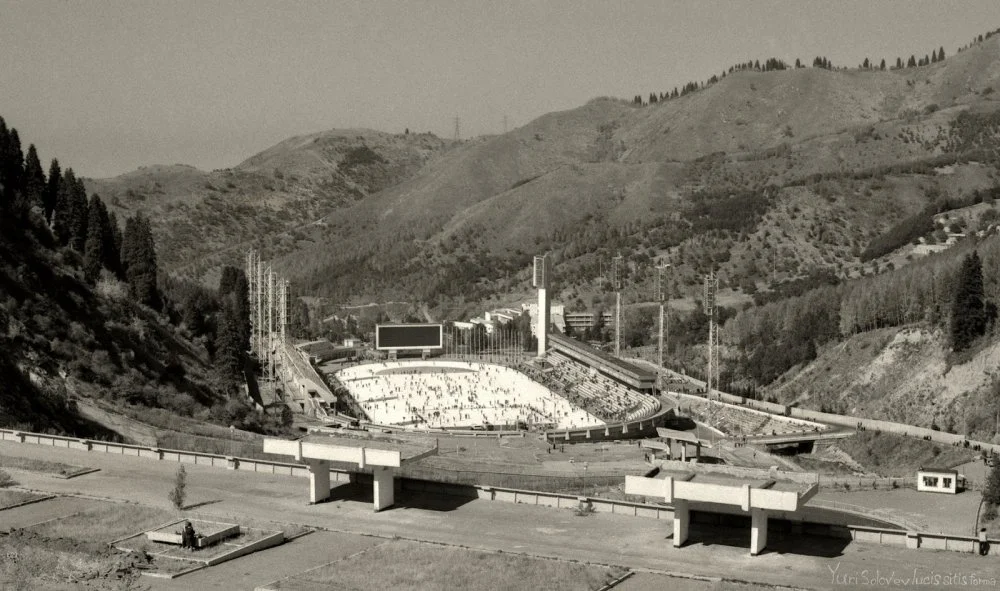

The second explosion took place in April 1967. The collapsed rocks formed a dam barrier 67 meters high and a mudflow reservoir with a capacity of 6.5 million cubic meters. Today, it is easy to understand the original height of the dam: the observation deck with white ‘checkmarks’, where the Lastochka Café was built, was its highest point.

Initially, the plan was to build a taller dam and two reservoirs, but at that time, it seemed that the problem had been solved. The dam not only made Almaty famous but also secured the city a place among the world’s major sports venues. As soon as construction began, it became possible to build a full-fledged arena for the Medeu skating rink, which had opened back in 1951 on natural ice. However, building a complete sports complex had been extremely risky: in the event of a mudflow, this expensive ice surface would have been the first to suffer. Therefore, until work began on the mudflow protection dam, the Medeu rink project had not been pursued.

In 1972, the dam was put into operation. Newspapers celebrated the victory over the elements—the city could sleep peacefully, no longer fearing mudflows:

By building an engineering structure at Medeu and scientifically determining its strength and lifespan, we are prepared to challenge nature—and we have no intention of yielding to it!

—S. Malakhov, head of the production department of the Kazakh Explosion Industry Trust

Many societies undergoing rapid industrialization have a rather utilitarian view of nature, and the Soviet Union was no exception. Mountains were to be conquered, the elements tamed, rivers reversed if necessary. There had been plans to erect a monument to the construction of the dam—a large sculpture depicting an explosion. But nature interfered with those plans.

15 July 1973

Ten years later, on 15 July 1973, which was also a Sunday, the moraine lake at the Tūiyqsu Glacier burst. The mudflow risk of this lake had been discussed as early as the 1960s, and special siphon spillways had even been installed to pump out the excess water. However, the dam’s construction and the expensive maintenance of the spillways caused water pumping from the lake to stop in the early 1970si

In less than ten minutes, the mudflow reached the Myñjylqy Dam and destroyed it. It then swept away a protective structure and part of the Gorelnik tourist base, where people were enjoying themselves at the time. The flow continued to gain strength and reached the Medeu mudflow reservoir, filling it almost entirely within a few hours.

The dam withstood the colossal impact, but engineering flaws soon began to appear. Stones and other debris quickly clogged the drainage channels, causing the water level to rise. The Lastochka Café was transformed into an emergency command center for several days. Immediate tasks had to be addressed: save the city, divert the threat from the newly opened skating rink, build an additional dam, reroute the Malaya Almatinka River through a pipeline, and install pumping stations.

Mr Ptero. View of Medeo Ice Rink. 2 October 1982 / Wikimedia Commons

At the same time, workers from Promventilation Trust used ventilation shafts to dry the leaks in the dam and simultaneously reinforced it with cement. To prevent new mudflow surges, a special team dropped smoke grenades near the Tūiyqsu Glacier from a helicopter. The smoke screen was intended to shield the glacier from the sun, thereby slowing down the heating and melting of the glacier.

The first emergency relief pumps only began operating on 20 July. By the end of the day, the water level slowly started to recede, and it became clear that the threat had passed. However, it also became evident that the forces of nature could not be fully tamed: once again, the Soviet press remained silent about the number of victims of this new incident.

«Almaty in the Embrace of the Dragon», «Kazakhstanskaya Pravda» newspaper, July 7, 2006 /National Library of Republic of Kazakhstan / Qalam

Thirty years later, in 2006, the journalist Oleg Kvyatovsky, who had been at the scene of the tragedy, published his memories in the newspaper Kazakhstanskaya Pravda in an article titled ‘Alma-Ata in the Dragon’s Embrace’:

Later, when everything had settled at the dam and nearby, Kunaev quietly and thoughtfully told the five of us journalists that there was no point in hiding the scale of the disaster and losses:

‘We will never know exactly how many died: the mountains were full of people, it was Sunday … I can tell you, but “off the record”, how many bodies were recovered and removed. Exactly seventy people …’

After pumping the water out, it was decided to increase the dam's height by another 40 meters and the reservoir’s capacity to 12.6 million cubic meters. Two more levels of stairs were built above the Lastochka Café. The idea of building a monument to the explosion was never discussed again.

According to scientists’ calculations, the force of the 1973 mudflow was four times greater than that of 1921. Moreover, based on scientific forecasts, mudflow activity is expected to increase rapidly in the coming decades due to global warming. The reinforced dam stands today as both protector and potential time bomb, its massive concrete walls waiting for the next inevitable confrontation with the mountain's wrath.

Akzel Beisembay. Issyk Lake has not yet returned to its size before the 1963 mudflow / Qalam