In Kazakh culture, bridal attire is far more than festive clothing—it is a complex code intertwining ancestral memory and the philosophy of a people. Professor Leila Makhat of the Kazakh National University of Arts explains the importance of the saukele, a traditional bridal headdress valued as highly as a herd of horses. She also discusses why the color red once held greater significance than white and reveals the sacred symbolism behind the wedding ensemble and its details.

- 1. The Visual Drama of a Wedding

- 2. ‘Kuda tusu’ («Құда түсу»): The Betrothal

- 3. ‘Kuyew kelu’ («Күйеу келу»): The Arrival of the Groom

- 4. ‘Kyz uzatu’ («Қыз ұзату»): The Farewell to the Bride

- 5. The Wedding Day: The Toi (Tой)

- 6. The Saukele as Relic

- 7. How Bridal Attire Evolved

- 8. A New Perspective on Tradition

- 9. The Fabric of History

- 10. What to read

Kazakh bridal attire is not simply something a bride wears on her wedding day—it is a deeply symbolic costume, with every detail infused with meaning, sacred beliefs, and the aesthetic traditions of the Kazakh people. It reflects not only ideals of beauty and wealth but also ancient beliefs and ethical values. Every fold of fabric, every ornament on the kamzol (traditional jacket), and every detail of the jewelry is part of ritual, culture, and collective ancestral memory.

Saukele. 19th century. From the A. Kasteyev State Museum of Arts exposition / Qalam

The central and most majestic element of a Kazakh bride’s wedding ensemble has always been the saukele—a tall, conical headdress that can reach up to 70 cm in height. The saukele serves as a visual symbol of a woman's honor, social status, and the beginning of a new chapter in her life. Its creation can take several months, and its cost was once comparable to that of an entire herd of horses.

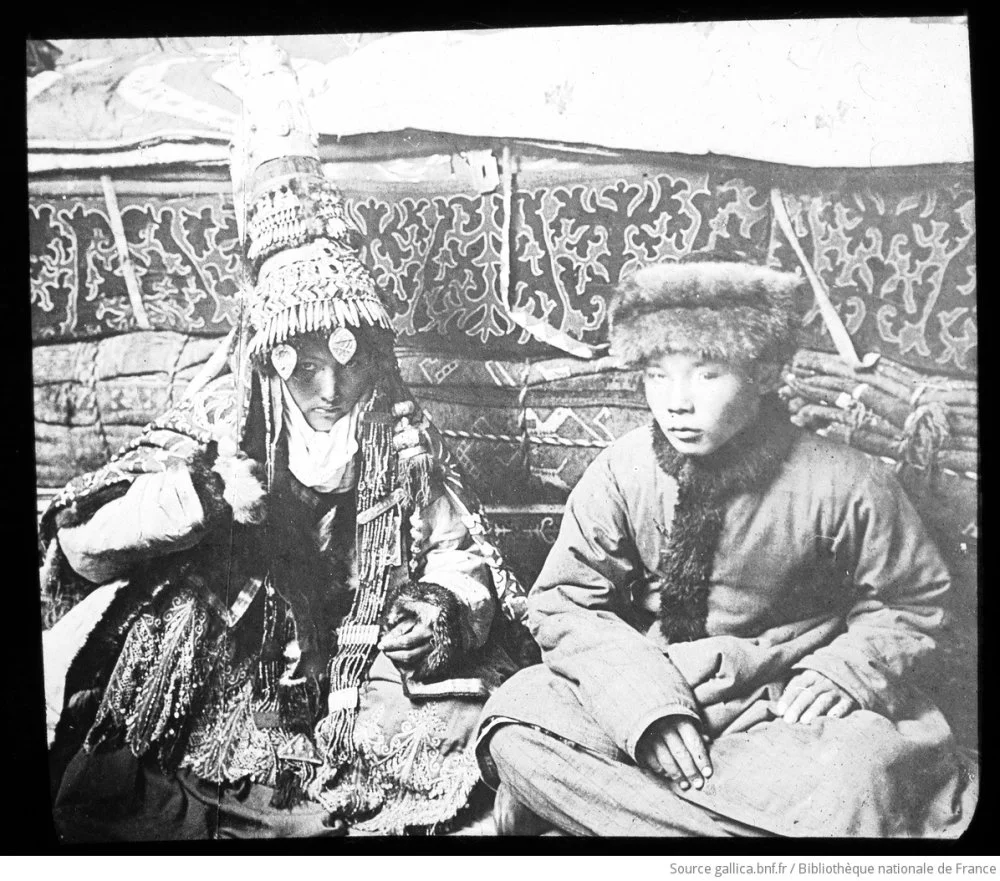

Young Kazakh bride. 19 century / Jules Marie Cavelier de Cuverville / Bibliothèque nationale de France / Gallica

The saukele is typically adorned with exceptional craftsmanship, traditionally using precious stones, pearls, and silver pendants, and invariably decorated with owl feathers, believed to possess the power to ward off evil. These elements were symbolic rather than practical, representing protection, transition, and prosperity. Silver, often included in the decorations, enhanced the costume’s ritual significance, symbolizing purity, blessing, and a connection to one’s ancestors.

Particular attention has always been given to the zhelek, a veil that covered the bride’s face, highlighting her transitional status. During the wedding ceremony, the bride is seen as a figure in between two worlds—childhood and marriage.

The bridal ensemble is complemented by ruffled dresses, velvet kamzols embroidered with traditional patterns, and an abundance of jewelry: earrings, bracelets, necklaces, and rings.

These pieces are often inlaid with precious and semi-precious stones. In Kazakh culture, stones have long held an important place as integral elements of protective and sacred symbolism. They are used in jewelry not only for their beauty but also for the benefits they are believed to bring to a person’s physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being.

Young Kazakh married couple. 19 century / Jules Marie Cavelier de Cuverville / Bibliothèque nationale de France / Gallica

Kazakh jewelers traditionally do not simply insert stones into jewelry—they select them according to the wearer’s age, social status, and life circumstances. For example, in adornments for young women and brides, turquoise and pearls are the most commonly used materials. Turquoise is considered a ‘living stone’ that protects the wearer against the evil eye, sudden death, and misfortune. Pearls symbolize purity and dignity.

Sholpy. 19th century. From the A. Kasteyev State Museum of Arts exposition / Qalam

Special attention is also given to hair ornaments. Sholpy and shashbau, attached to braids, produce a gentle, melodic chime that is believed to drive away evil spirits. This jewelry is carefully matched to a woman’s age and social standing. In childhood and early adolescence, Kazakh girls wear miniature silver sholpy, often without pendants, serving as a first adornment and a symbol of the ‘open’ and unformed state of the maiden soul. These pieces feature symbols of the sun, moon, and birds—metaphors of growth and protection.

Shekelik. West Kazakhstan, 19th century. From the A. Kasteyev State Museum of Arts exposition / Qalam

In adolescence and at the age of marriage, Kazakh girls transition to heavier sholpy and shashbau—these hair ornaments are now adorned with tiny bells, fine granulation, and motifs of flowers, animals, and the cosmos. This stage of life is seen as one of heightened vulnerability, and so protective tamga (ancestral clan symbols) are woven into the jewelry. After marriage, women typically wear understated yet weighty shekelik (ornaments attached to loops on the headdress or to the hair at the temples) and have other elements integrated into the headdress, as can be seen in the kimeshek. The symbolic language of the adornments has evolved over the years, with the introduction of motifs like circles, spirals, and the eternity symbol.

The Visual Drama of a Wedding

A traditional Kazakh wedding is not a single-day affair but a layered sequence of rituals, each imbued with symbolic meaning and requiring careful preparation, including the meticulous selection of the bride’s garments. Bridal clothing is more than ceremonial—it is deeply meaningful and is a marker of social and spiritual status, representing her transition from girlhood to womanhood as she passes through the wedding’s many phases.

‘Kuda tusu’ («Құда түсу»): The Betrothal

This is the formal proposal and negotiation of the marriage agreement. While the bride does not actively take part in this stage, preparations for her role have already begun—her dowry is assembled, and the saukele, along with other components of her wedding attire, is commissioned.

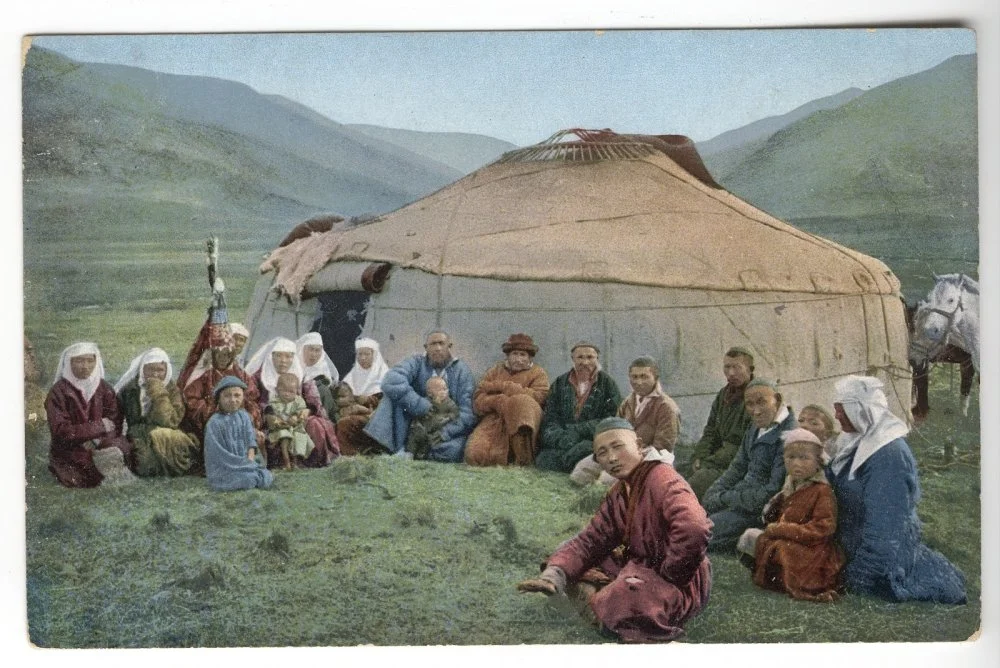

РК Kazakh family wedding setting. Aktobe Region, 1926–1927 / CSACPSR RK

‘Kuyew kelu’ («Күйеу келу»): The Arrival of the Groom

The bride is dressed modestly, in pale shades that signify purity.

‘Kyz uzatu’ («Қыз ұзату»): The Farewell to the Bride

This ritual marks the bride’s departure from her family home—a pivotal moment. She wears a vivid, celebratory gown, richly embroidered and adorned. Her head is crowned with the saukele, a powerful emblem of both maiden purity and new social standing. The bride’s face is covered with a zhelek (a bridal veil). Traditionally, this bridal ensemble was red.

Saukele and shapan. Kazakhstan, 19th century / From the A. Kasteyev State Museum of Arts exposition / Qalam

In Kazakh culture, red represents the vitality of life, youth, and energy, which is why it has traditionally been reserved for women on significant occasions, such as weddings, coming-of-age rites, and major ceremonies. In ritual terms, the colour signifies a woman’s passage into marriage. A red kamzol or saukele has thus become a visual representation of that transformation. Further, since red fabric, especially velvet and brocade, was typically a luxurious material that was accessible only to the affluent, the presence of red in bridal clothing also signaled noble lineage, prosperity, and high social rank.

The Wedding Day: The Toi (Tой)

Akes place at the groom’s home. The bride’s attire often remains the same as during the ‘Kyz uzatu’ (Қыз ұзату), but special attention is given to the betashar ceremony—the unveiling of the bride’s face. During this ritual, the zhelek concealing the bride’s face is slowly and ceremonially lifted, symbolizing her acceptance into the groom’s family. Sometimes, a second bridal ensemble is worn on this day, lighter in color, but with the same symbolic elements: a kamzol, traditional bridal jewelry, and a headdress.

Samuil Dudin. Rich bridal costume with headdress and breast ornaments (front view), Semipalatinsk, 1899 / Hamburg Museum of Ethnology / CSACPSR RK

After the wedding, the young wife continues to wear a zhelek, no longer as a face-covering veil, but as part of her daily head covering, until the birth of her first child. This could take the form of a scarf, a shawl, or a draped covering, symbolizing modesty and the bride’s new social status. Each stage of a woman’s life thus calls for a distinct set of garments, also reflecting the family’s prosperity. The color scheme shifts over time: red before marriage; white or light tones after marriage; and reserved, subdued shades in maturity. Simultaneously, headdresses, from the simple tyubeteika to the elaborate saukele, from the modest zhaulyk to the ceremonial kimeshek, visually express a woman’s age, status, and ritual role.

The Saukele as Relic

The saukele does not vanish from a woman’s life after her wedding. It is passed from mother to daughter, from grandmother to granddaughter, as a symbol of the maternal lineage. Outsiders are not allowed to touch it—it is believed that the saukele preserves the spiritual strength of the family. It is, therefore, often kept in a separate, clean, and protected space, wrapped in white cloth or placed in a special chest (sandyk) to shield it from dust, light, and decay. Sometimes, a red chest is used, emphasizing the item’s festive and sacred nature. This chest is placed in a quiet corner of the yurt or house, often alongside other items from the dowry.

Samuil Dudin. Kazakhs of the Semipalatinsk Region. 1899 / Romanov Empire

The saukele is thus preserved not merely as a memento, but as a cherished heirloom—a protective family talisman and a symbol of continuity in the maternal line. It is sometimes brought out for recollection, to show guests, particularly during ‘kudagi shay’ (құдағи шай)i

Sergey Borisov. Group of Kazakhs by a Yurt. 1911–1913 / Library of Congress

The saukele is believed to embody the spirit of the clan and the woman’s honor, and so it is never to be worn or even tried on by others, especially unrelated girls. After the wedding, the bride might wear it again for festive occasions during her first year of marriage; subsequently, it is preserved as a symbolic relic, a sacred thread linking generations.

How Bridal Attire Evolved

Over the past century, Kazakh bridal attire has transformed dramatically, serving as a cultural document that mirrors the sweeping changes in society. One of the primary forces behind this shift has been the modernization of public life. With the advent of Soviet rule came a policy of uniformity and a rejection of what was labeled ‘feudal or religious remnants’—a category that included national dress. The saukele, protective amulets, and rituals such as betashar and kyz uzatu were seen as outdated and ideologically inappropriate. Gradually, these elements were pushed out of everyday life and replaced by simplified garments, often stripped of any ethnic identity.

A second major factor was urbanization, which led to a fundamental change in lifestyle. The transition from a nomadic way of life to a settled existence—from yurts to apartments, from clan-based communities to nuclear families—redefined the very concept of a wedding. In the urban setting, the ornate and expensive saukele was no longer practical. Western-style dresses came to symbolize modernity, European sophistication, and affluence.

The third key influence on the transformation of bridal wear was the rise of mass media and globalization. From the late twentieth century onward, Kazakh society became increasingly immersed in global information flows dominated by Western cultural imagery, conveyed through television, film, glossy magazines, and, later, the internet.

Siez Basibekov. Wedding. Talas District, Dzhambul Region, 1965 / CSACPSR RK

The white wedding dress—emblematic of innocence and femininity—became a near-universal symbol of the bride, gradually displacing the traditional ethnic garments. Yet perhaps the most nuanced factor in this evolution was a shift in attitudes toward tradition itself. For previous generations, bridal attire was part of a sacred rite, a spiritual act. For modern brides, it is more often a form of self-expression, fashion, and aesthetic choice. Although interest in traditional clothing is making a comeback, it is now primarily decorative rather than ritualistic in nature.

A New Perspective on Tradition

Still, these changes do not carry a strictly negative meaning. Instead, they reflect the dynamic evolution of a culture capable of adapting, of finding a balance between tradition and modernity. In a surprising twist, the perception of national dress has recently been notably influenced by the growing popularity of the performing arts. It is no secret that this cultural medium holds a special place in Kazakh society, alongside contemporary fashion trends.

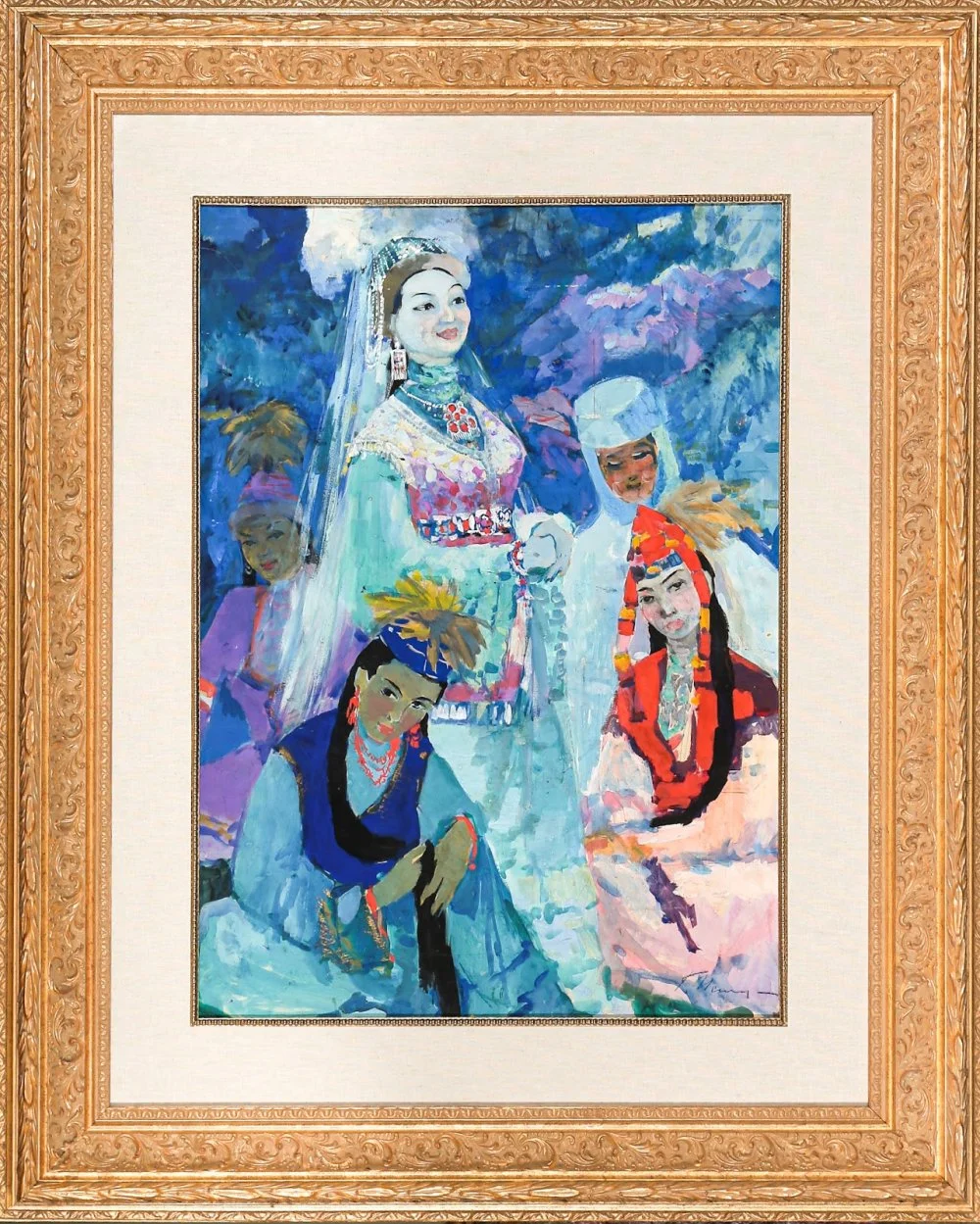

Gulfairus Ismailova is a name inseparable from Kazakh theater and the national style of stage design. As a set designer, painter, thinker, and bearer of Kazakh aesthetic tradition, she left a significant mark on the traditional dress—especially through the lens of theater and the visual language of the stage.

Ismailova Gulfairus. Sketch for the painting «Kulyash Baiseitova». Paper, mixed media. 75x54 cm / bonart.kz

One of the most striking aspects of her approach was the deliberate amplification of ornamentation in costumes for plays with Kazakh themes. Ismailova understood that theater is not a museum, and that the stage demands heightened visual expression. To ensure that even audience members in the back rows recognized the distinctly Kazakh nature of the performance—that it was not just a generic Eastern story—she would exaggerate details: enlarging patterns, deepening color contrasts, and enhancing decorative elements.

Noble Kazakh woman. «Turkestan Album», 1872 / Library of Congress

This technique carried not only artistic value but also cultural weight. It elevated traditional ornamentation from a modest design element to a symbolic, recognizable structure, restoring its sacred dimension and giving it modern visual power. At a time when the national imagery was often diluted by Soviet stylistics, such an emphasis became a form of visual resistance, a way to declare: this is a Kazakh story, this is a Kazakh symbol.

Thanks to Ismailova’s visual strategies, Kazakh traditional attire found renewed life on the stage. No longer just an ethnographic artifact, it became a visual language—an instant identifier of the performance’s cultural context, even without knowledge of the plot. Moreover, her influence extended beyond theatre, into the realm of contemporary fashion.

Oleg Svidin. Kazakh national ritual "Seeing off the bride", Guryev city, 1991 / CSACPSR RK

In recent years, costume designers, fashion designers, and stylists have begun to use enlarged patterns and bold color accents as a way to represent national identity in contemporary interpretations of fashion. Thus, Ismailova’s art became a bridge between tradition and modernity, the stage and the runway. Her work transformed the very perception of the Kazakh costume: it expanded its meaning, turned details into symbols, and made ornament a voice of culture.

Z. Tamayeva. Wedding couple — students of AIPFL (KAUIR&WL) near a yurt. Almaty, 1989 /CSACPSR RK

Ismailova’s approach demonstrated that national dress is more than an accessory—it is a powerful, expressive language, capable of speaking to audiences across any distance, from the stage to the heart.

This is, in its essence, a unique and powerful example of how visual art can shape society. The new aesthetic vision created by Gulfairus Ismailova has become a lasting cultural phenomenon of the modern era.

The Fabric of History

Today, we are witnessing a new reinterpretation of the visual, chromatic, and aesthetic codes of the nomadic world in the context of contemporary life. Especially encouraging is the young generation’s growing interest in the roots of Kazakh culture.

Returning to the topic of bridal attire, as an artist and researcher, I would like to highlight the importance of the meanings embedded in ancient Kazakh traditions. This is the language through which our ancestors expressed their ideas of beauty, honor, and spirituality.

Young Kazakh bride. 19 century / Jules Marie Cavelier de Cuverville / Bibliothèque nationale de France / Gallica

Yes, many rituals have lost their relevance to our daily lives. But the sacredness of the images, the rhythm of the ornaments, and the color codes of tradition remain tools of cultural memory that continue to function—so long as we know how to read them. As long as there is interest in these meanings, as long as the fabric of history is not forgotten, Kazakh culture is not just alive—it is evolving, revealing itself in new forms.

Leila Makhat is an artist, a gallery curator, and a professor at the Kazakh National University of the Arts, with a PhD in Fine Arts.

Alexandr Pavsky. Theatrical performance of the ancient wedding during Nauryz celebrations. Almaty region, 1989 / CSACPSR RK

We express our gratitude to the Abylkhan Kasteev State Museum of Arts of the Republic of Kazakhstan and to the Bonart.kz auction house and gallery for kindly providing the illustrations for this article.

What to read

1. Исмаилова Г. Ш. Театр. Живопись. Судьба. — Алматы: Өнер, 1986.

2. Татимов М. Б. Национальные традиции казахского народа. — Алматы: Казахстан, 1993.

3. Аманжолова Д. И. Казахский национальный костюм: историко-этнографический анализ. — Алматы: Ғылым, 2001.

4. Кунаев А. И. История традиционной казахской культуры. — Нур-Султан: Ел Орда, 2012.

5. Кожахметова К. А. Свадебные обряды казахов: ритуалы и символика. — Алматы: Өнер, 2007.

6. Уалиева Р. Одежда казахов: культурное наследие кочевников. // Вестник КазНУ. Серия культурологии. 2015. №2.

7. Ашимбаев М. С. Казахские обряды и традиции в современном обществе. — Нур-Султан: Институт культурной политики, 2018.

8. Назарбаева С. Этноэстетика: казахский орнамент и его значение. — Алматы: Қазақ университеті, 2010.

9. Сабденова Г. Влияние театрального искусства на визуальный код казахской национальной одежды. // Искусство и общество. 2020. №4.