Written by Qalam’s regular contributor, film historian Alexei Vasilyev, this series of essays explores the oeuvres of the greatest Eastern film directors from different times. The portrait gallery continues with the Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

This is the second part of the Great Directors from Asia series. The first part can be read here.

Crime and Punishment

In 1974, a seventeen-year-old teenager in Tehran, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, a member of an anti-Shah group for two years, attempted to disarm a policeman at a check post and take possession of a gun by stabbing him with a knife. The boy was sentenced to death, but taking his age into account, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

Four and a half years later, after the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Makhmalbaf and other political prisoners were released under an amnesty, and some years later, he became a famous film director. The policeman Makhmalbaf had stabbed survived; however, he was unable to adjust to life after the revolution. He responded to a casting notice Makhmalbaf had placed in the newspaper for a new film, Hello Cinema (Salam Cinema, 1995). It would seem that he hoped that the man who had destroyed his life with a wave of his hand would also, with a wave of his hand, give him a new, different life and make him an actor.

This encounter in 1994 led Makhmalbaf to the idea of making a film about this long-ago incident. To prepare for filming, he chose two young men to play himself and the policeman with the idea of working in pairs. He got the policeman he attacked to teach the actor how to stand guard, handle weapons, maintain order, culminating in him leading the actor to the check post by the same route he took that day. In his own turn, Makhmalbaf would instruct his own ‘double’ in his own actions the same way. When the time came to film, the two young actors would meet at the exact spot where the real event happened years ago. A film crew would be waiting there to capture their performance, a reenactment of that dramatic encounter.

This is the starting point of the plot of A Moment of Innocence (Nūn o Goldūn, 1996) by Mohsen Makhmalbaf, a man known as the Iranian Jean-Luc Godard. However, the comparison with the Frenchman, who repeatedly drove all his machinery into the frame and who used film quotations and political slogans to make colorful cinema, the enjoyment of which depended directly on the viewer’s knowledge of the films and newspaper headlines he referenced, diminishes the effect of the Iranian film as its appeal does not rely on these factors.

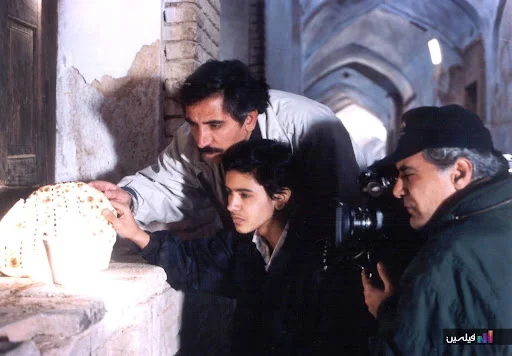

“The Moment of Innocence” 1995/IMDb.com

Generally speaking, cinema often achieves the best results when it talks about itself. Many of the films about films and how they are made have won over not only movie buffs but also the widest audience, with The Stunt Man, Monstrous, Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood immediately coming to mind. But this short (seventy-eight-minute) Iranian film, which by default denies the director’s fantasy, serves as an illustrative lesson in filmmaking. The director demonstrates how to reenact and film a specific, significant episode from his own life, which divided it in two. Shot with non-professional actors, around whom the desolate everyday life of Tehran in the winter goes on, this film became the very drop of dew on the native threshold in which the universe is reflected. The image of black hijabs and white snow turns into a climax of spectral colors for the viewer, while the two-syllable story turns into the sign of infinity.

Makhmalbaf has a contagious sense of humor, which we’ll talk about in a moment, but by the time he made A Moment of Innocence, he had amassed vast and varied cinematic experience. It is almost impossible to capture the sensual pleasures and philosophical insights of the world in a single experience and space. It is as if you must have a touch of magic, or be kissed on the forehead by a higher spirit, to achieve this. And we should credit those who can manage it because not all of us are touched by genius.

Of course, the premise of the film itself is a good one: it includes the inscription from King Solomon’s ring—‘This too shall pass’—and the Marxist assertion that society develops as a spiral, not a vicious circle. Two men who devastated each other’s lives meet twenty years later in a new society in the same homeland, and create a balm out of the old wound—the result is a great movie for one and an acting career for the other. When the forty-year-old men teach the seventeen-year-old actors their own youthful habits, the snow falling in drifts is a perfect companion. It has made the roads impassable, driving people and cars off them. Under the sleepy twilight sky, the two groups of men, the old and the young, horse around: one teaches the other how to march and stretch, and the other two are surprised by the similarity of their love stories. The cabin of a car, freezing under the thawing snow on a suburban highway, and a hotel room are the islands of warmth where they share the most intimate things, not only across generations but also across a changed world, flags, law, and ideology. It is clear that no matter how you change the flags, men and boys will still end up talking about love and dreams.

“The Moment of Innocence” 1995/IMDb.com

The policeman is stretched out on a hotel bed. The nature of the cheap room reminds him of the barracks where he once dreamed of love in the same way, but did not share his dreams with his peers. The presence of a boy and being of an age that has freed him from adolescent inhibitions brings back this missed opportunity. As it turns out, there is an important nuance that explains why his reflexes were slow enough for him to be stabbed that long-ago day: it was all about a girl.

Male and Female

In the Shah’s Iran in the 1970s, only Googoosh1

Meanwhile, Makhmalbaf takes his young self to his female cousin’s home and tells the audience his love story. He gave her books to read, and she always returned them with the paragraphs she’d liked underlined and a dried flower between the pages. They were politically active together. In the past, he’d been watching this policeman for a long time and had encouraged her to distract him at his post. It turns out that the actor has exactly the same love story, with his cousin, with dried flowers in books—only this one is not about violence, it’s about peace and universal equality.

“The Moment of Innocence” 1995/IMDb.com

What follows is the most mysterious scene, because everything else, as it should be in a good detective story, comes together in an unbreakable knot at the end. Makhmalbaf’s cousin also went to jail but was soon released. She married someone else and now has a seventeen-year-old daughter, and Makhmalbaf wants to engage this daughter to play the role of the cousin. While Makhmalbaf argues with the cousin, who won’t permit her daughter to reenact this shameful story on screen because Allah will punish both her and Makhmalbaf if she does, she does it in a funny, touching way—the daughter runs through the snow to the car where the boy has stayed, bringing him sweets, asks when and where the filming will take place. She is sad that her mother won’t let her go, and suddenly blurts out, ‘Do you have a book?’ The boy pulls out a folio and warns her not to make any marks in it, and she hides it under her hijab.

“The Moment of Innocence” 1995/IMDb.com

A Moment of Innocence has many interpretations, and the one from the late president of the Busan International Film Festival Kim Jiseok deserves special mention. He broke the movie into parts, numbered them, and examined the intersection of film, reality, memory, fiction, and fact to determine the objective reality contained in it. The scene we have just discussed, however, he simply ignored. Less incisive critics would (and did) say that the conversation between contemporary teenagers who don’t know each other becomes a scene from Makhmalbaf’s memory, which flooded his mind at his cousin’s house, where he used to hand her books in the same way. However, the young man is sitting in a modern car, and Makhmalbaf did not drive in those days anyway. The scene would be more believable and charming if we assumed that the actor already knew Makhmalbaf’s niece: the ways of seventeen-year-olds are inscrutable to older people and are often kept secret. Young people get to know each other more easily, and it is quite natural for a seventeen-year-old boy to sincerely court two girls at the same time. But that’s just my interpretation that I can offer since that’s how I’m comfortable and happy to understand this scene. Either way, it opens up the hermetic construction of A Moment of Innocence into a fourth dimension, hinting at its presence to uncover an ultimate cosmic truth.

“The Moment of Innocence” 1995/IMDb.com

Next, as we know, the film’s parallel storylines—Makhmalbaf and the policeman, film and reality, memory and the here and now—begin to converge. Makhmalbaf takes his young self to the school where the young performer’s cousin’s classes are ending. Walking home with her, and handing her another impressively large book that was also hidden under his shirt, he explains the nature of the scene to be filmed, and when they part, the girl decides to rehearse. In the gallery of the covered market, she notices a very young policeman at his post, exactly what she needs, and when she passes by, she asks what time it is. This policeman is our young actor, practicing his moves under the guidance of the former policeman. As the girl moves on, the former policeman steps into the gallery from the street and says, ‘There! That’s exactly how it happened.’ There are two groups of people here involved in a common game in a movie—only they don’t know it yet. The guys are also unaware of the catch: the girl is playing from a script that contains a trick for them.

“The Moment of Innocence” 1995/IMDb.com

At this point, I will allow myself an important digression: this girl is extraordinarily beautiful. It’s as if Natalie Portman from Luc Besson’s Leon had grown up without losing a drop of her youthful freshness. The fact is that every Makhmalbaf film guarantees an encounter with an incredibly beautiful girl, who is captivating precisely because of her blossoming, which promises the ripeness of the fruit but not yet the fruit itself. And no two films are alike. If you think that Emir Kusturica is the champion of young beauties among directors, he has nothing on Makhmalbaf. After all, Makhmalbaf shoots more—he has made more films starring women from all over the world because after he began to be censored in Iran in the 1990s, he made half of his films outside the country.

It is also part of a director’s talent to find, even among non-professionals, such magnificent specimens who will also be able to fulfill the acting tasks before them. And Makhmalbaf achieved the most magical results in Tajikistan, where he lived for several years. The results of these experiences were the Didor International Film Festival in Dushanbe, which he founded in 2004, and three feature films. In the film Sex & Philosophy (2005), Tahmineh Ebrahimova—tall, slender, with long, silky hair and a graceful silhouette, dressed either in a blue fur coat swinging around her heels or in a fantastic white silk doctor’s gown—enchants the viewer with her proud, commanding posture and Modiglianesque2

Makhmalbaf's favorite actresses

From Iran to Tajikistan

Makhmalbaf’s Tajik debut, Silence (1998), was about a blind boy who tunes tars (stringed instruments from the lute family). The character was full of masculine arrogance, strangely inadequate for his age and condition, stubbornly following his own impulses and intoxicated by local pop. In the film, one scene at the market is utterly unique: on his way to work, the blind boy loses his way and, like the victims of the Pied Piper, follows a man from whose hip a transistor radio hangs blaring the melody of Oleg Fesov’s [3] hit song of the time, ‘Charo Mamepursi’ (‘Why don’t you ask?’). In his thick cap of light blond hair and the composure of his face, I saw my deceased childhood friend, astonished by the total coincidence of this image with a person from a completely different country unknown to Makhmalbaf. But I was even more amazed to learn that the boy was actually played by a Tajik girl, which says something about Makhmalbaf’s phenomenal ability to find and reveal the charming attributes of a girl that transcend not only nationality but also gender.

Western critics like to speculate about the political symbolism in Makhmalbaf’s Iranian and Afghan films, which are full of the contrasts between bars, enclosed spaces, dizzying desert labyrinths, female and male pastimes, and there is a palpable common sense in their arguments. The Sufis and Bahá’ís, who tend to lump his Iranian Gabbeh (1996), Tajik Silence, and Israeli The Gardener (2012) together as a trilogy, see his filmmaking as the perfect expression of their religions—and they are surely right, too.

Makhmalbaf is indeed one of those directors who are particularly open to interpretation. His method involves taking real-life stories, reenacting them with real participants, and showing the viewer that they are no longer in conflict, but are acting out the conflict together, giving everyone a chance to come closer to the truth. The truth is one, and there is room in it for the smaller truths of individual religious, political, and philosophical beliefs. It would take many volumes to outline and confirm every truth reflected in Makhmalbaf’s films. But we are limited to one article, and I will focus on one thing: since childhood, cinema, for me, is first of all about laughter and then meeting incredibly beautiful people. So I salute Makhmalbaf as the greatest master of sending viewers on blind dates with stunning girls—because he picks his actors from the crowd and rarely uses them more than once. This, too, is his great and unique gift.

Laughter and Joy

As for laughter, it is the beautiful cousin who provokes it in A Moment of Innocence, and she is the one in the frame who derives the most pleasure from the provocation. When the boy who plays Makhmalbaf sees her after school, he begins to tell her about his desire to feed humanity and make everyone happy. She interrupts him: ‘Can you say the same thing, about saving humanity, but in a village accent?’ So the boy switches his speech and says, ‘Awright, dinnae yi’ll waant tae be th’ mither o’ a’ mankind?’—and the girl continues on her way, now beaming with joy. When she reaches the market and stops at the bread shop, he asks her why she made him do that and she replies: ‘It’s funnier that way.’

Makhmalbaf was, however, not inclined to make fun of everything and everyone from an early age. His films from the 1980s are full of revolutionary rhetoric, exuding an assertive, relentless, and rather standard string of words and ideas, similar to the slogans of Imam Khomeini that adorn the walls of his Marriage of the Blessed (1988): ‘The land belongs to the hut dwellers’ and ‘We will bring the capitalists to the hall of justice.’ Humor began to permeate his films and became a dominant feature in the cinephile comedy Once Upon a Time, Cinema (1992), a kind of hit parade of the stars of Iranian cinema, through which Makhmalbaf also told the story of the state’s recent history. For example, there was a place in it for Qeysar (the hero of the eponymous film), who slit the throat of an enemy, his naked body pressed against the other man’s in a shower stall; for the bloody palm of the beaten-to-death Reza from Reza, the Motorcyclist on the screen of a movie theater; and for the shah’s words that very accurately reflected the mood of Iranian films of the 1970s: ‘Cameraman, we want to get drunk so we can become as famous as movie actors.’

As Makhmalbaf’s daughters grew up, humor took an increasingly important place in his cinematography. After the death of his wife, he married her sister Marzieh, with whom Makhmalbaf seems to have had a relationship based on their shared interest in cinema. Then taken together with the films she directed, it seems clear that she is a woman of a light, laughing nature. Thus, it is no coincidence that a schoolgirl relative becomes the vehicle of laughter and humor in A Moment of Innocence, and the humor itself takes on the characteristics that would come to dominate the films produced by Makhmalbaf and his women. It is not a calculated wit or a clownish gag, but a laughter that erupts involuntarily when, for example, we hear a person with an accent trying to talk about fashion, art, or the sublime.

Director Mohsen Makhmalbaf (R) and his first wife Hana Makhmalbaf attend the Opening Ceremony and 'Birdman' premiere during the 71st Venice Film Festival, August 27, 2014 in Venice, Italy/ Dominique Charriau/WireImage)

It is this contrast between language and content, the imperfect command of the language and the matter in question, that is the charm of Sex & Philosophy, in which Tajik actors speak in Russian. The very first sentence of the film— ‘Hi, it’s John!’—becomes the key device of the film, especially since it is repeated at least four times (John is pronounced Jeong). Outside John’s windshield lies the decaying Soviet-era Dushanbe of the mid-noughties. He has forty candles lit on the glove compartment in front of him because it is his fortieth birthday, a strangely poetic touch for a guy in a rundown city. Makhmalbaf had already been living in Tajikistan for two years when he made the film—he was remarkably sensitive to the many nuances of the post-Soviet consciousness of people in their forties, whose youth and fantasies had been shaped by perestroika in the second half of the 1980s.

John, played by Daler Nazarov, a songwriter and performer who has been famous since the 1980s, is the head of the dance school in the film. He composed the magical song ‘Charo Amepursi’ from Silence. His dancers are dressed like Antonio Gades’s flamenco troupe, and while this may seem like a random detail, it is actually a very subtle observation about the characters’ past. Amongst the first signs of perestroika in Russia was the huge success of Carmen (1983) by Carlos Saura, which was voted the best foreign film released in the USSR in 1985 by readers of The Soviet Screen. It was a film about the rehearsal of a flamenco performance, and it is, incidentally, somewhat similar to Makhmalbaf’s films about rehearsals, using real events as inspiration, which, in the camera’s gaze become fiction, a game, while new relationships developed during the game become reality.

John has a long relationship with the four women he decided to bring together for an anniversary party. Two of them wear red-and-black clothes with men’s headdresses, a tasteless fashion combination popular in the late 1980s Soviet rock scene with bands like Alisa and their female fans. Sergei Solovyov’s films, inspired by the world of the rock underground, also featured this style with his leading actress (and wife), Tatyana Drubich, dressed in the same kind of hideous clothes. This tastelessness turned out to be ineradicable, as it became a part of the characters’ youth. What happens is so ridiculous and funny that sometimes, the girls from the corps de ballet can’t stand it and start laughing off-script—like when Farzona, who wore different colored shoes the day she met John to provoke him, every time their dance circle of ‘little swans’ makes a turn and she finds herself facing John, tries to pounce on him, shouting: ‘Don’t forget, it’s these shoes that made you fall in love with me!’

Sex & Philosophy 2005/Alamy

The characters are all filled with creative energy, inspired by directors like Saura and Solovyov, but fail to see the difference between being enthusiastic and the professionalism required to create a dance or a film. Makhmalbaf often addresses this difference in his films, but nowhere is it more vividly portrayed than in Hello Cinema, in which girls on the verge of a nervous breakdown talk about their love of cinema, but when the director asks them to cry or laugh, they can only produce ridiculous squirms and grimaces, highlighting the difference between their passion and their actual skills. In Sex & Philosophy, the situation is a little more complicated. To begin with, the characters are very impressionable and their ideas of beauty are not always constant. They also mix vivid examples of high art with no less vivid examples of tastelessness. For example, let’s consider the red roses that are so abundantly present in Makhmalbaf’s frames. They’re filmed in a way that truly highlights their beauty, like perfect roses shot against a background of a brilliant blue for a postcard. Such an idea of beauty was used in Egyptian films like Sea Demons (1972), which Soviet companies dealing with foreign movies purchased in huge numbers to brighten the lives of the inhabitants of Central Asia and the Caucasus. These areas, also home to people without much formal education, had a greater cultural connection to such themes. Thus, these movies offered a beauty that was easy to understand and enjoy.

Sex & Philosophy 2005/Alamy

The Cry of Ants and Pity for the World

Of course, the film’s characters, dreaming of art but being completely incapable of it, are pathetic—like the Afghan cripples in Kandahar (2001) who, after being blown up by mines, run on their crutches like sprinters behind a Red Cross helicopter, dropping their prostheses to be the first in line. But these same cripples are selling them on the street for a fortune an hour later, explaining to foreigners that these prosthetics are expensive because they belonged to their beloved deceased mother and have more value as a memory. Similarly, in Makhmalbaf’s Indian film Scream of the Ants (2006), a man writes the ultimate wisdom in invisible ink to an Iranian pilgrim girl who has traveled an arduous path to reach him. He hands her a parchment saying the writing will become visible if she holds a candle to it on the banks of the holy Ganges in Benares. When she does, she finds that the inscription reads, ‘I’ve traveled all around the world to see the rivers and the mountains, and I’ve spent a lot of money. I have gone to great lengths, I have seen everything, but I forgot to see just outside my house a dewdrop on a little blade of grass, a dew drop which reflects in its convexity the whole universe around you.’ This ‘revelation’ is the well-known, especially in India, advice that Rabindranath Tagore gave a young Satyajit Ray, who would become a giant of Bengali cinema, in the 1940s. In the context of a pilgrim, it reads: ‘Go back to where you came from!’

The sub-genre of comedy in which Makhmalbaf works is that of the greedy, the boastful, and the foolish characters, which often change places. In the middle of Scream of the Ants, the pilgrim laughed when the Indian taxi driver turned the car halfway around to return a fly to the ‘stop’ where it had flown into the cabin. But the very Indians she had laughed at the previous day were making fun of her, to the extent that judging by her enlightened expression, she does not realize she has been tricked. The mocking and the mocked sometimes switch places, like the tyrant in Makhmalbaf’s Georgian film The President (2014), played by Mikheil Gomiashvili. One day he is turning the lights on and off all over the city for his grandson’s amusement. But the next day, he is forced to be a typical Eastern street performer, a duo usually comprising an adult singer/musician and his fidgety boy dancer (very much like the duo from Disco Dancer) to blend into a crowd of poor people and share his fate with the very people who were so fed up with his fiddling with electricity that they started a revolution.

Makhmalbaf’s films rarely use laughter to mock; instead, it is the kind of jovial laughter that accompanies any struggle for survival, however it is fought. Sometimes, Makhmalbaf laughs at the way even his own leg has been pulled. In the quasi-documentary The Gardener, Makhmalbaf and his son, Maysam, play the roles of bad cop and good cop while filming a Bahá’í colony4

Family Portrait Indoors

Makhmalbaf’s humour is completely unfettered when he writes scripts for the women in his family, like his daughter Samira and his wife, Marzieh. He taught them, as well as his son and youngest daughter, Hana, at his own film school, which he founded after making A Moment of Innocence. At this point, he seems to have begun to feel that he had made such a great film that he should no longer make films but filmmakers instead! Indeed, the seventeen-year-old Samira’s debut, The Apple (1998), went straight to Cannes. As in Makhmalbaf’s films, the protagonists play out a real-life incident in front of the camera. The blind wife of a poor sixty-five-year-old man somehow miraculously gave birth to twins, and the old parents kept the girls locked up, unwashed, uneducated, and barely able to speak. A disaster worthy of Chaplin’s Modern Times begins when the social worker locks the old man up in the ‘prison’ where the girls were kept and hands him a saw to free himself. As the bespectacled old man saws and weeps, he shouts: ‘I can’t take it anymore!’, while the girls are released into the street, where one of them takes an ice cream from the boy vendor, without paying, of course, as she doesn’t understand money. While he chases after her, the other one takes three ice creams from his freezer, gives the goat present in the scene a lick as well, and then eats the rest. That’s freedom, equality, and hygiene for you.

Iranian director Samira Makhmalbaf and her father writer and director Mohsen Makhmalbaf pose 20 May 2007 upon arriving at the Festival Palace in Cannes for the screening of the collective film “To Each His Own Cinema” at the 60th edition of the Cannes Film Festival/ Anne-Christine Poujoulat /AFP via Getty Images

The legless young Afghan nobleman in Samira’s Two-Legged Horse (2008) is an incredibly funny character: the servant boy he (literally) rides has left him hanging by the arms from the ropes of a swing, and the turbaned nobleman, dangling under the rung, is shouting to the courtyard: ‘Take me down, asshole!’ The hunchbacked old woman in Marzieh’s The Day I Became a Woman (2000) is funny and magnificent. When the island of Kish is declared a free-trade zone, she decides to finally live life to the fullest and buys all sorts of household appliances, including a luxurious, state-of-the-art music system and a bed under a tippet. To transport her purchases to her ship, she hires nimble young black boys who have stolen hijabs from Iranian girls to use as sails. It was Mohsen, of course, who invented all these unlikely heroines who defy common sense and turn the world into a fiesta of disobedience.

Cinema, of course, is the ultimate fiesta of disobedience, and who would know better than an Iranian director working under strict censorship. Even in the very serious, even tearful Marriage of the Blessed (1989), Makhmalbaf incorporated an exquisitely funny scene. A newspaper reporter, tasked with ‘focusing on societal shortcomings but presenting them in a palatable form’, and his fiancée film beggars and thieves on the streets of Tehran at night: some steal a wheel from a parked car, while others fiddle with a payphone in the booth to get the change. Suddenly sirens wail, and the police appear, but their only interest is in the reporter: Does he have a permit to take pictures? What is this woman doing with him? Suddenly, the blackness of the night is pierced by searchlights, revealing the presence of Makhmalbaf’s crew shooting the film we are now watching. They have a permit, and the police don’t touch them, though they mutter: ‘What are you filming? There’s nothing to film here!’ In the end, the reporter and his fiancée are taken to the detention center, and the thieves, who have been sitting on the floor of the phone booth all this time, get up and, exhaling with relief, continue to dismantle the payphone with the same zeal.

Makhmalbaf himself became the cause of a double act of disobedience: a real hoax—a fraud in the eyes of the Iranian court—and a film about that hoax. A poor man, who had no money to buy his son’s medicine, got on to a bus with a brochure on Makhmalbaf’s The Cyclist (1989). This film is a dizzying piece of editing (Makhmalbaf always edits his films himself and impeccably at that) and magnificent cinematography by the virtuoso veteran Ali Reza Zarrindast, who used to shoot ‘in the style of Vilmos Zsigmond’.5

A Moment of Innocence, in which Makhmalbaf reconstructs an incident from his youth in which he and a policeman point a dagger and a gun at each other, ends with the young actors also pointing two objects at each other. More precisely, they hold them out to each other: a flatbread and a potted flower. But the actor, who was a baby in the days of the revolution, a child during the Iran-Iraq war, and who grew up in the peaceful and rather liberalized society of the early 1990s, could not imagine threatening his peer, another Iranian boy, even with a fake knife, so he threw the knife away on the way to the set. The actor playing the policeman picked up a flower pot to give to the girl who asked what time it was. But the girl jumped aside so that her friend could ‘stab’ the policeman with the knife, and the boy to whom the other boy held out the flower, in his confusion, automatically decided to offer him a present, and held out the flatbread, because that was what he was holding in his hands.

This final still has been called the greatest in the history of cinema. As with any game, that’s the peculiarity of cinema: you play out a former grudge against the perpetrator, and it’s gone. Even the policeman who had been dreaming about the girl from 1974 for twenty years forgave Makhmalbaf for his ‘wasted’ life—because no life is miserable and wasted if a movie tells people about it and if it makes them laugh.

The first part of the Great Directors from Asia series can be read here.

Mohsen Makhmalbaf poses on March 10, 2015 in Paris, a week before the release in France of his movie "Le President"/ LOIC VENANCE/AFP via Getty Images