The economies of nomadic states, when viewed through a ‘settled’ lens, are often described as ‘simple’ merely because they lacked large-scale manufacturing, dense urban centers, and financial institutions as we understand them today. In truth, however, this description misunderstands them entirely. These were not ‘simple’ at all; instead they followed a distinct model that was carefully adapted to its unique environmental and social conditions.

In the steppe, economic efficiency was not determined by the scale of production or the density of cities but by mobility and the ability to adapt quickly to a changing environment. It was on these principles that the economy of the Kazakh Khanate was informed and functioned. In this article, Qalam explains how nomads created one of the most flexible and well-designed economic models of the late Middle Ages.

- 1. Trade, Travel, and Relay Stations: How the ‘Internet’ of the Thirteenth Century Worked

- 2. The Cities of the Golden Horde

- 3. The Economy of the Kazakh Khanate

- 4. Pastoralists, Farmers, and Pirates

- 5. The Currency of the Khanate

- 6. The Cities of the Khanate

- 7. A Picture of Everyday Life

- 8. The Economy of Freedom

Trade, Travel, and Relay Stations: How the ‘Internet’ of the Thirteenth Century Worked

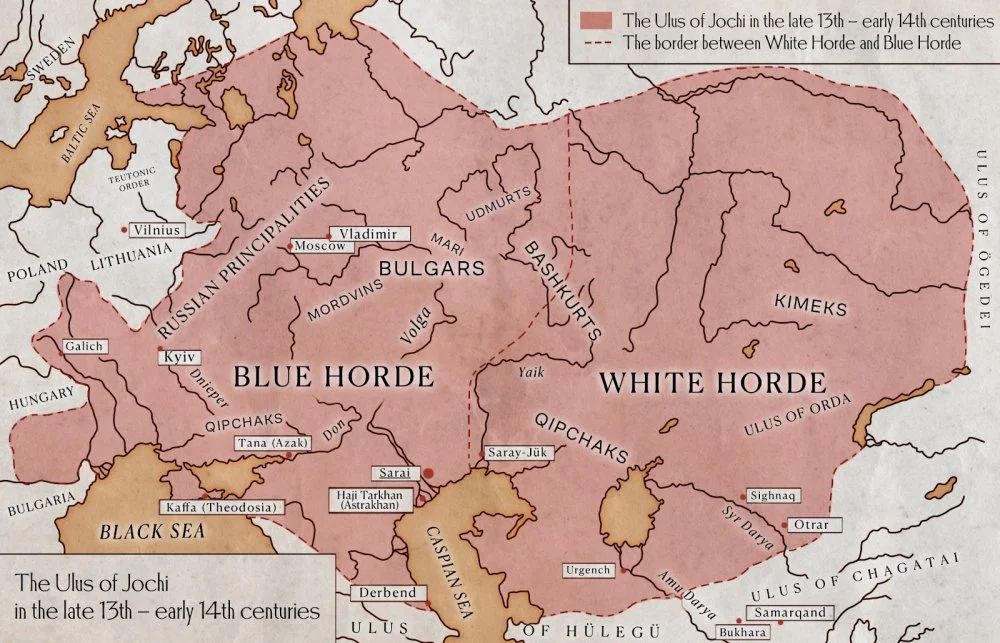

The economy of the Kazakh Khanate inherited much from the practices of the Ulus of Jochi, also known as the Golden Horde. It carried forward systems of taxation and duties, trade routes, and mechanisms of security and collective responsibility. The foundation of the Golden Horde’s economy was nomadic pastoralism, and horse breeding was at its core. The horse was a strategic resource, as vital in its time as oil in the twentieth century. It functioned simultaneously as a means of transport, a weapon, a commodity, and a measure of wealth. Without horses, war could not be waged, goods could not be transported, and control over the vast territories along Eurasia’s key trade routes could not be maintained.

The Battle of the Terek (1262/1263) between the Golden Horde and the Hulaguid State. Illustration from an illuminated manuscript, early 15th century / Wikimedia Commons

In this transcontinental trade, the Ulus of Jochi was a central player. By controlling various networks of roads and ensuring the unhindered movement of people and goods, the Horde turned its domains into the most important transit corridor between the East and West. Caravans carrying Chinese silk, Indian spices, and Iranian textiles passed through its lands, moving via Sarai and the Volga region to Crimea, and from there on to Western Europe.

The efficiency of this route was largely ensured by the alliance between the Ulus of Jochi and the Genoese Republic, which was one of the principal trading powers of the Mediterranean. They controlled main ports on the Black Sea and sought stable supplies of goods from Asia. The Golden Horde, in turn, maintained control over the overland routes across the vast steppe, without which such trade would have been impossible.

Genoese consuls. Illustration from an Illuminated manuscript, late 13th century / Wikimedia Commons

As a result, a mutually beneficial system emerged: Italian merchants traded freely in Jochid lands, paid customs duties, and received caravan protection, access to infrastructure, and safeguards against arbitrary actions by local authorities in return. In the Middle Ages, when wars and banditry often disrupted trade routes, such predictability was rare, and this is precisely why transit trade became one of the key sources of income for the khan’s authority.

To manage this system, the Ulus of Jochi required constant communication between distant regions. Thus, an extensive communications network that was ahead of its time emerged in the khan’s lands. Along the main roads—from Siberia to the Danube and from the Volga region to Crimea—yams, or postal and transport stations at every 30 to 50 kilometers, were established. Fresh horses, on-duty guides, and supplies of food and clothing were available at all times—everything merchants and travelers needed to ensure that their journeys continued uninterrupted. In addition, with couriers and horses being regularly relayed, messages could travel up to 500 kilometers per day, a speed unimaginable by medieval standards.

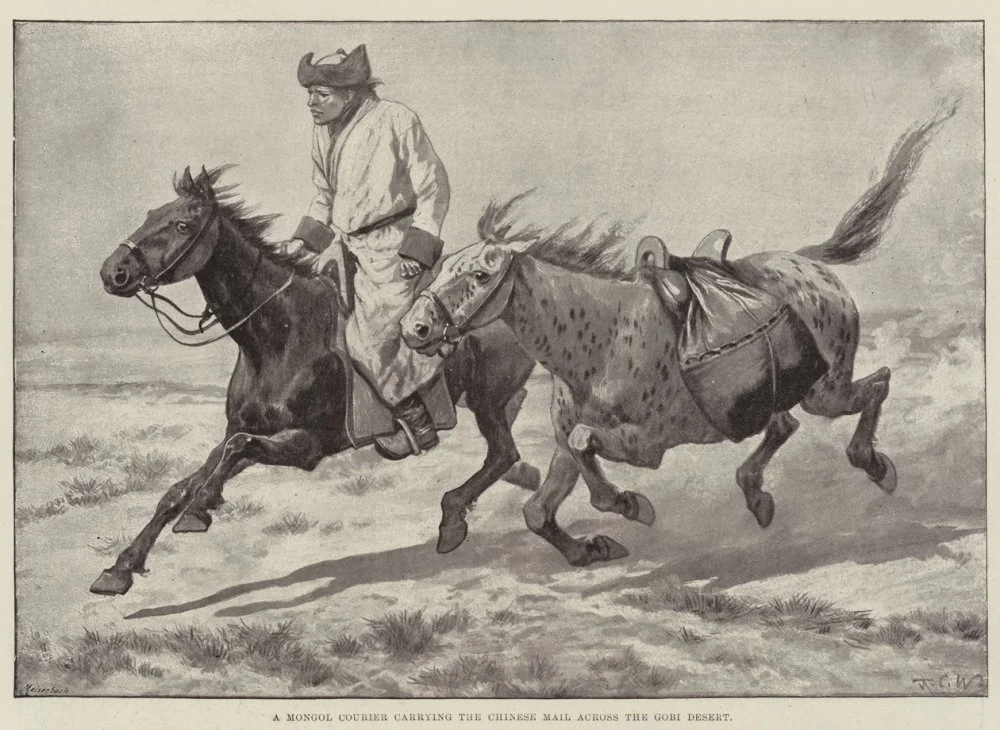

A Mongol courier carrying a letter across the Gobi Desert / bridgemanimages.com

Security was also a key condition along these routes. If a caravan was attacked and robbed, the local population was held responsible, and the damages were compensated collectively. In essence, this was an early form of insurance—another reason why merchants willingly chose these routes.

The Cities of the Golden Horde

Over the years, the long-held notion that nomads were merely destroyers of cities has been thoroughly debunked. In the Golden Horde, urban centers formed a vital component of the economic and administrative system. For example, the cities of the Ulus of Jochi were tangible expressions of statehood. They housed officials, served as centers for tax and customs collection, sustained markets and craft quarters, and minted coinage. These hubs connected the steppe with the settled world and enabled long-distance trade.

Qalam

These cities also functioned as crucial administrative hubs overseeing economic life. As early as the thirteenth century, the Golden Horde conducted censuses, with designated officials recording population figures, livestock numbers, and land resources. These records were used to levy taxes and allocate administrative resources, underscoring the systematic and well-organized nature of governance in the Ulus of Jochi.

The Economy of the Kazakh Khanate

After the collapse of the Golden Horde, its economic model was largely inherited by the Kazakh Khanate. Pastoralism remained the foundation of the economy, and the khanate soon became one of the largest centers of horse breeding in the late Middle Ages. Well into the nineteenth century, it maintained more livestock than any comparable territory, both in absolute numbers and on a per-capita basis.

In the khanate, horses, sheep, and camels were not merely sources of food or a means of transport. They were valuable commodities, diplomatic gifts, and symbols of status and power. Livestock functioned as a form of universal currency: it was exchanged for textiles, weapons, and grain. In fact, the autumn livestock drives to Bukhara and Samarkand usually turned into large-scale fairs, drawing traders from across the region.

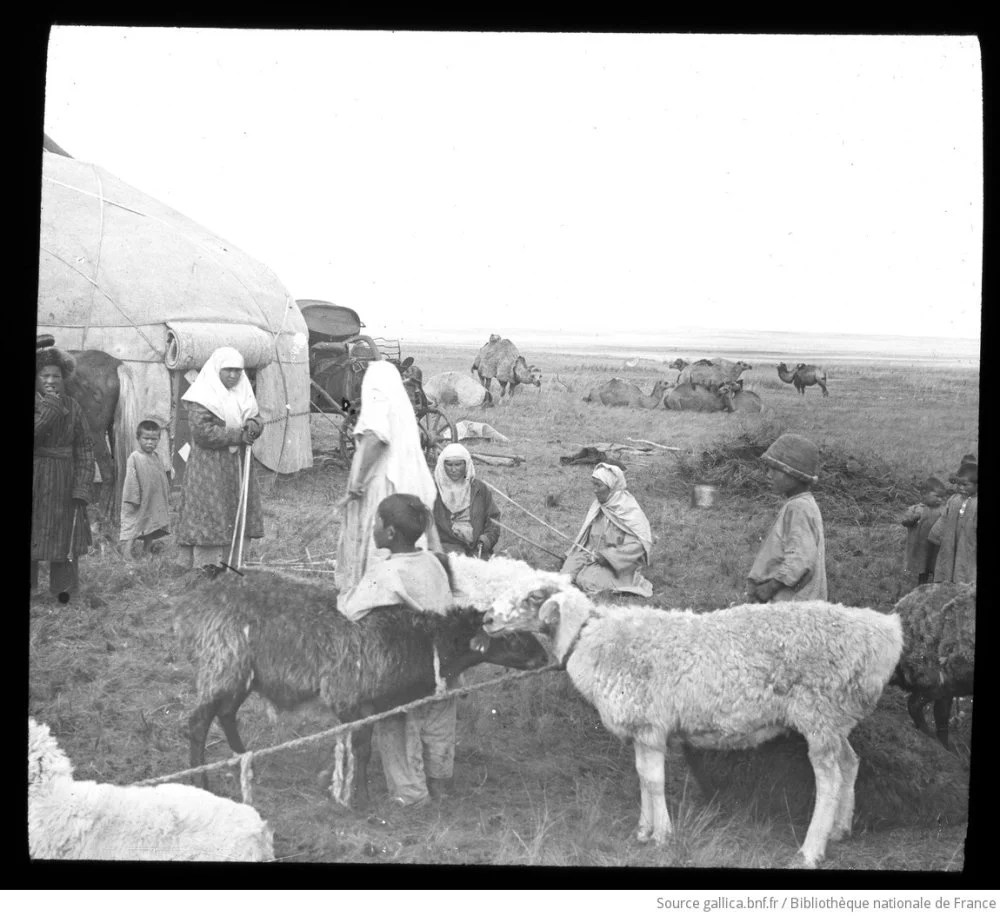

An Oirat caravan. Early 20th century / Wikimedia Commons

Surpluses of livestock sometimes led to falling prices, a form of overproduction typical of any economy. In response, Kazakh pastoralists sought out new markets. Horses were driven as far as India, where their price increased dramatically, increasing by tens or even hundreds of times: from just a few dinars in the steppe to hundreds in South Asia. In the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, livestock was also driven to Dagestan and Moscow. Along with the horses themselves, legends of steppe steeds, renowned for their beauty and exceptional endurance, spread across the world, capturing the imaginations of distant lands.

Pastoralists, Farmers, and Pirates

The economic structure of the Kazakh Khanate was not uniform and was primarily shaped by the natural conditions of individual regions. For example, in the vast steppes of Saryarqai

The western regions of the Kazakh Khanate were characterized by a more arid climate. Under these conditions, breeding camels and sheep—animals better adapted to sparse vegetation and limited water resources—was a greater priority. Alongside pastoralism, fishing also played a significant role here, a feature uncommon to most other parts of the khanate.

Jules Marie Cavelier de Cuverville. Shearing the rams / Bibliothèque nationale de France / Gallica

The Kazakhs living along the shores of the Aral and Caspian Seas, as well as in the steppes near the Urals, were actively engaged in fishing and maritime activities and even owned their own vessels. By the nineteenth century, the residents of these areas were often sought out by foreign merchants for their skill as sailors. In fact, some sources even mention episodes of piracy in the Caspian Sea, hinting at a little-known maritime dimension of steppe life.

The Currency of the Khanate

In the Kazakh Khanate, almost anything of value could be used as currency. Although coins were no longer minted as actively as they had been under the Golden Horde, money continued to be used as the primary means of payment. Taxes and levies, in particular, were paid in money. Numismatic finds confirm that Kazakh khans pursued an independent monetary policy: archeologists and researchers have uncovered coins issued in the names of Tauke Khani

That money circulated even among the common people is evidenced by Kazakh folklore: historical epics and proverbs frequently mention monetary units such as tenge, tiyn, tilla, som, pula, and altyn.

Coins of Tursun Khan, 16th century / Wikimedia Commons

However, money was not the only medium of exchange—the system of bartering remained common. People often paid each other directly with goods, and one of the most widely used measures of wealth was possessing a year-old ram. A fine chapani

The Kazakh Khanate also skillfully navigated relations between the Russian and Qing empires, using this geopolitical balance to secure valuable trade privileges. The Kazakhs had access to Chinese tea—a monopolized commodity—which they exchanged for livestock. Over time, compressed tea bricks became a fully accepted form of currency along caravan routes. The Kazakhs’ role in the international tea trade was significant enough to attract attention far beyond the steppe, and documents from 1864 show that it was even discussed in the British Parliament.

Compressed pu-erh tea / Getty Images

The Cities of the Khanate

Cities in the Kazakh Khanate, as in the Golden Horde before it, remained a key link between the nomadic steppe and the sedentary world. They facilitated the exchange of goods, connected the khanate to international trade routes, and served as significant economic and administrative centers.

The cities along the Syr Darya—including Sygnak, Yassy, Sozak, Sauran, and Otrar—held particular significance. It was here, in these fortified urban centers, that trade was concentrated, markets operated, fairs were held, and caravans converged. Through these cities, nomads gained access to craft goods, textiles, grain, and items of urban life, while the sedentary population obtained livestock and products of the nomadic economy.

Sart musicians. Tashkent, between 1885 and 1890 / Library of Congress

The bulk of the urban population consisted of the so-called sarts, or sedentary Turkic-speaking inhabitants who engaged in crafts and trade. They produced goods, serviced markets, and maintained the economic infrastructure of the khanate. Thus, cities were not opposed to the steppe but complemented it, making the economy of the Kazakh Khanate more resilient and diverse.

A Picture of Everyday Life

For an ordinary Kazakh family, wealth was measured primarily by the size of their herd. A household with 300 to 500 sheep and up to a hundred horses was considered modest and not particularly wealthy. Yet, even such families rarely faced food shortages, since livestock provided meat, milk, hides, transport, and trade goods throughout the year. Indeed, in a nomadic economy, livestock provided a reliable foundation for daily life.

By the standards of the late Middle Ages, the Kazakh diet was abundant. Meat and dairy products were available all through the year: mutton, horse meat, kumisi

Kazakh Meal, between 1865 and 1872 / Library of Congress

Livestock served not only as a source of food but also as an economic reserve. It could be exchanged, sold, given as a gift, or used to support relatives and neighbors in difficult years. Thanks to this, the economic system of the steppe was relatively flexible, enabling it to endure adverse periods including droughts, jutsi

The Economy of Freedom

The economy of the Kazakh Khanate was not a rigid system governed by formal codes or regulations. It developed under the influence of climate, vast open spaces, and a nomadic way of life. Nomads remained free: if conditions no longer suited them, they could, and would, simply move on.

This freedom became an economic principle—freedom of movement, choice, and exchange. The system relied on a balance between individual initiative and collective responsibility, between humans and nature. There were no factories, yet trade, taxes, insurance, and credit thrived, all grounded in personal honor and mutual trust. Perhaps this is the key to understanding the Kazakh Khanate’s economy: wealth was measured not in gold, but in the ability to remain free.

Learn more about the economy of the Kazakh Khanate on the Qalam History channel.